Resource-Backed Loans: The collateral clauses that mortgage futures

Why it matters:

- Resource-backed loans are a significant financial mechanism in developing countries, involving pledging future resource revenues as collateral.

- While offering immediate financial relief, these loans can lead to long-term economic burdens and governance concerns.

Resource-backed loans have become a significant financial mechanism in developing countries, particularly those rich in natural resources. These loans involve a borrower securing funds by pledging future resource revenues, such as oil, gas, or minerals, as collateral. Critics argue that while these loans offer immediate financial relief, they often result in long-term economic burdens. It is essential to understand how resource-backed loans function and their implications for the borrowing countries.

According to a 2022 report by the Natural Resource Governance Institute, approximately 30% of resource-rich developing countries have engaged in resource-backed borrowing in the past decade. The primary appeal of these loans lies in their accessibility. For countries with limited options to access capital markets due to poor credit ratings, resource-backed loans provide a viable alternative. However, the absence of stringent transparency measures often shrouds these agreements in secrecy, leading to concerns about governance and accountability.

Resource-backed loans typically include clauses that specify the volume and value of resources pledged, repayment schedules, and interest rates. These agreements often lack standardization, which can lead to terms that disproportionately favor the lender. For instance, interest rates on these loans can exceed international lending norms by 2 to 3 percentage points, significantly increasing the cost of borrowing.

The impact of these loans extends beyond immediate financial obligations. They can affect a country’s economic sovereignty and resource management strategies. When resources are used as collateral, governments may face restrictions on how these resources are extracted and sold. This can lead to environmental concerns and limit the country’s ability to negotiate better terms for resource exploitation.

The following table provides a snapshot of the countries most involved in resource-backed borrowing as of 2023, detailing the estimated value of their obligations and the primary resources involved:

| Country | Estimated Loan Value (USD Billion) | Primary Resources Used as Collateral |

|---|---|---|

| Angola | 25 | Oil |

| Venezuela | 50 | Oil |

| Ghana | 10 | Gold |

| Mongolia | 7 | Coal and Copper |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | 15 | Cobalt and Copper |

The implications of resource-backed loans are multifaceted. While they provide much-needed infrastructure development and fiscal stability, they also pose risks of increased debt burden and economic distress. Countries like Angola and Venezuela have faced significant challenges due to fluctuating commodity prices, which have made it difficult to meet loan repayments. These situations often lead to renegotiations that can result in even more stringent terms.

Moreover, the lack of transparency in the negotiation and execution of these loans raises questions about their legitimacy. In several instances, the public remains uninformed about the terms of these agreements, leading to public discontent and political unrest. The complexity of these loans and their long-term implications necessitate a comprehensive understanding of their structure and impact on national economies.

While resource-backed loans offer immediate financial solutions, they also mortgage the future economic prosperity of the nations involved. It is crucial for countries considering such loans to weigh the immediate benefits against potential long-term consequences. Implementing transparent and accountable governance frameworks is essential to ensure that these loans contribute positively to national development without compromising future economic stability.

Historical Context and Evolution of Resource-Backed Loans

Resource-backed loans (RBLs) have a long and intricate history that has evolved alongside global economic trends and geopolitical shifts. Originating in the early 20th century, these financial instruments have been utilized by nations rich in natural resources, yet poor in financial capital. The concept is relatively straightforward: countries pledge future natural resource revenues as collateral to obtain immediate financing. Over the decades, this mechanism has shaped the economic landscapes of several developing nations.

The initial use of RBLs can be traced back to the early 1900s when countries like Brazil and Venezuela used them to secure funds for infrastructure projects. During this period, the loans were primarily structured with private investors from industrialized nations, seeking access to valuable commodities like oil and rubber. The economic boom post-World War I further fueled this trend, as the demand for raw materials surged.

In the latter half of the 20th century, the landscape of RBLs began to change. The 1973 oil crisis marked a significant turning point. Oil-rich nations in the Middle East and Latin America found themselves in a position of power, utilizing RBLs to leverage their commodity wealth against financial markets. This period saw an expansion in the types of resources used as collateral, including minerals and agricultural products, reflecting the diversified global demand.

During the 1980s and 1990s, the debt crisis in Latin America highlighted both the potential and pitfalls of RBLs. Countries such as Mexico and Argentina faced significant economic challenges as fluctuating commodity prices rendered them unable to service their debts. This era underscored the inherent risks associated with RBLs, particularly when tied to volatile markets.

The turn of the millennium witnessed a renewed interest in RBLs, driven by the rapid industrialization of China and its insatiable appetite for resources. China’s Belt and Road Initiative further catalyzed the use of RBLs, as it sought to secure resources from Africa and Latin America to fuel its economic expansion. This period also saw the emergence of new players, including state-owned enterprises and multilateral lenders, reshaping the dynamics of RBLs.

Today, RBLs continue to be a double-edged sword for resource-rich nations. While they provide critical funding for development projects, they also pose significant fiscal risks. The following table illustrates the evolution of key RBLs over the past two decades, highlighting their impact on national economies:

| Country | Year | Resource | Loan Amount (USD Billion) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angola | 2004 | Oil | 2.0 | Infrastructure development, increased debt burden |

| Ecuador | 2009 | Oil | 1.7 | Economic boost, repayment challenges |

| Ghana | 2011 | Cocoa | 3.0 | Improved infrastructure, fiscal strain |

| Venezuela | 2014 | Oil | 5.0 | Economic turmoil, political unrest |

| Zambia | 2016 | Copper | 1.5 | Mining growth, increased debt load |

The evolution of RBLs underscores the need for careful consideration and strategic planning. Countries must balance the immediate benefits of infrastructure and economic growth against the potential for long-term indebtedness. The instability of commodity prices remains a critical factor, as evidenced by historical examples where countries struggled to meet their financial obligations due to market fluctuations.

Additionally, transparency and accountability in the negotiation and execution of RBLs are paramount. The lack of public disclosure has often led to mistrust and political instability, as citizens remain unaware of the commitments made by their governments. Implementing robust governance frameworks and ensuring informed decision-making processes can mitigate some of the risks associated with these loans.

While RBLs have evolved to address the changing needs of the global economy, their historical context provides valuable lessons. Understanding the complexities and potential consequences of these financial instruments is crucial for nations considering their use. As the demand for resources continues to grow, the role of RBLs in shaping economic futures remains significant, necessitating a careful and informed approach.

Key Players in the Resource-Backed Loans Market

Resource-backed loans (RBLs) are complex financial instruments that involve multiple stakeholders with varied interests and influences. These loans are typically facilitated by a range of key players, each of whom plays a crucial role in the negotiation, execution, and management of these agreements. Understanding the dynamics and motivations of these participants is essential to grasp the broader implications of RBLs on global economic and political landscapes.

Government Entities

Government entities from resource-rich countries are primary actors in the RBL market. These governments seek to leverage their natural resources to secure financing for infrastructure projects, economic development, and sometimes to bridge fiscal deficits. Countries like Angola, Zambia, and Ecuador have historically engaged in RBLs to fund public works and bolster economic growth. However, the reliance on future commodity revenues as collateral poses significant risks, particularly when commodity prices are volatile.

International Banks and Financial Institutions

International banks and financial institutions are pivotal in providing the capital for RBLs. Entities such as the Export-Import Bank of China, the Development Bank of Latin America, and other major financial institutions have been at the forefront of these transactions. These banks offer loans at interest rates that may be more favorable than traditional lending, but the loans come with stringent repayment conditions tied to resource outputs. This dependence on resource extraction aligns the interests of these banks with the continued production and export of commodities from borrowing nations.

Commodity Trading Firms

Commodity trading firms, including giants like Glencore, Trafigura, and Vitol, play an instrumental role in facilitating RBLs. These firms often act as intermediaries, purchasing future outputs of resources to secure loan repayments. They benefit by obtaining resources at predictable prices, which they can then trade on global markets. This involvement provides these firms with considerable leverage over the economic policies of resource-rich countries, often influencing decisions related to resource management and export strategies.

Multinational Corporations

Multinational corporations engaged in the extraction and processing of natural resources are also key players. These corporations, such as ExxonMobil and Rio Tinto, may enter into agreements with governments as part of RBL arrangements. Their investments and operations in resource extraction can significantly impact the economic stability of the borrowing country, especially if the repayment of loans is dependent on the success of these operations.

International Organizations and Regulatory Bodies

International organizations and regulatory bodies, including the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, although not directly involved in RBLs, influence the market by setting guidelines and providing oversight. They often urge transparency and best practices in the negotiation and implementation of these loans. These organizations advocate for accountability and sustainability in resource management, aiming to prevent the adverse effects of excessive indebtedness on developing economies.

| Key Player | Role | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Government Entities | Negotiate and secure loans using natural resources as collateral. | Angola, Zambia, Ecuador |

| International Banks | Provide financing with conditions tied to resource outputs. | Export-Import Bank of China, Development Bank of Latin America |

| Commodity Trading Firms | Purchase future resource outputs to secure loan repayments. | Glencore, Trafigura, Vitol |

| Multinational Corporations | Engage in resource extraction and processing. | ExxonMobil, Rio Tinto |

| International Organizations | Provide guidelines and oversight to promote transparency and sustainability. | IMF, World Bank |

The RBL market is characterized by a diverse array of influential players, each with their own interests. The interactions between governments, financial institutions, trading firms, multinational corporations, and regulatory bodies create a complex web of dependencies and motivations. For borrowing countries, navigating these relationships requires a careful balance of immediate financial needs against long-term economic and environmental sustainability. The actions and decisions of these key players will continue to shape the future of resource-backed lending and its impact on global economies.

The Mechanics of Resource-Backed Loans: Collateral Clauses

Resource-backed loans (RBLs) have emerged as a significant financing mechanism for many developing nations, offering a method to access capital by utilizing natural resources as loan collateral. These loans, however, come with intricate collateral clauses that can bind countries to long-term commitments with significant implications. Understanding the mechanics of these collateral clauses is crucial for evaluating their potential risks and benefits.

Collateral clauses in RBLs typically stipulate that a borrower pledges future resource production or reserves in return for immediate financial support. This arrangement enables countries to secure funds for infrastructure development, social programs, or debt refinancing. However, these clauses often lack transparency and can lead to unfavorable terms for the borrowing nation.

Government entities, in their pursuit of financial support, negotiate the terms of these collateral clauses. This process involves not only evaluating the current value of resources but also projecting future market conditions. For instance, Angola has entered into agreements where future oil production is used as collateral, thus binding its economic future to fluctuating oil prices.

International banks play a pivotal role in structuring these loans, often tying conditions to the loan that require the borrower to commit significant portions of their resource output. The Export-Import Bank of China, for example, has extended numerous loans to African nations, using copper and oil as collateral. This arrangement gives the lending institution considerable influence over the borrower’s resource management and economic policy.

Commodity trading firms further complicate the dynamics of RBLs by purchasing future resource outputs to secure loan repayments. Firms like Glencore and Trafigura engage in contracts that allow them to acquire resources at predetermined prices, which can be advantageous if market prices rise but detrimental if they fall. This creates a scenario where the borrowing nation’s economic stability is closely tied to these firms’ trading strategies.

Multinational corporations involved in resource extraction often become indirect players in these agreements. Corporations such as ExxonMobil and Rio Tinto may enter into agreements with governments that align with the terms of RBLs. These corporations’ operations can impact local economies and environments, raising concerns about sustainability and social responsibility.

| Key Element | Description | Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Collateral Pledge | Future resource output used as loan security | Potential loss of resource control and revenue in case of default |

| Loan Conditions | Terms dictating resource management and economic policy | May limit financial flexibility and sovereignty |

| Commodity Pricing | Pre-agreed prices for future resource output | Market volatility risk affecting repayment burden |

| Corporate Involvement | Extraction firms influencing loan agreements | Environmental and social impact considerations |

International organizations such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank are increasingly stepping in to provide guidelines aimed at promoting transparency and sustainability in RBL agreements. These organizations advocate for clear reporting practices and encourage borrowing nations to carefully assess the long-term economic impact of their collateral commitments.

For borrowing nations, the challenge lies in negotiating terms that align with national interests while ensuring that immediate financial needs do not overshadow future economic sustainability. This requires a strategic approach to resource management, recognizing both the opportunities and risks inherent in resource-backed financing.

The complex interplay of these factors highlights the importance of robust governance frameworks and informed decision-making processes. Nations must navigate these collateral clauses with an understanding that their natural resources, once pledged, bind their economic futures to the terms agreed upon today. As the global landscape of resource-backed lending continues to evolve, the mechanics of collateral clauses will remain a critical area of focus for policymakers, economists, and international observers.

Charts

Economic Impact on Borrowing Countries

Resource-backed loans (RBLs) have become a prevalent financial tool for countries rich in natural resources but lacking capital. These loans allow borrowing countries to access funds by using their natural resources as collateral. While offering immediate financial relief, RBLs can impose significant economic implications on borrowing nations, influencing both their short-term fiscal maneuverability and long-term economic trajectory.

The primary economic impact of RBLs on borrowing countries is the alteration of their fiscal space. When natural resources are used as collateral, they are effectively earmarked for debt repayment. This earmarking limits the ability of countries to leverage these resources for other developmental projects or economic diversification. Countries with heavy reliance on a single commodity face amplified risks, as fluctuations in global commodity prices can impact their ability to meet debt obligations, leading to increased borrowing costs and fiscal instability.

One of the critical challenges for borrowing countries is the potential for a debt trap. When loan agreements lock in future resource revenues, countries may find themselves in a cycle of borrowing to service existing debts. This situation is exacerbated by volatility in commodity markets, which can decrease resource revenues below anticipated levels, pushing countries to negotiate new loans under less favorable terms. For instance, between 2020 and 2025, several African countries experienced a significant rise in debt-to-GDP ratios, partly attributed to resource-backed borrowing.

| Country | Debt-to-GDP Ratio (2020) | Debt-to-GDP Ratio (2025) | Resource-Backed Loans (2020-2025) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Angola | 120% | 130% | $15 billion |

| Chad | 45% | 60% | $3 billion |

| The Republic of Congo | 80% | 95% | $5 billion |

Environmental implications also play a significant role in the economic impact of RBLs. The extraction of natural resources often leads to environmental degradation, which can have long-term economic costs. For borrowing countries, the need to adhere to environmental regulations and mitigate damage requires additional investments, potentially offsetting the financial benefits obtained through RBLs. In some cases, the economic costs associated with environmental damage can exceed the short-term financial gains, leading to net negative outcomes.

Additionally, the economic impact of RBLs is closely tied to governance and institutional capabilities. Countries with weak governance structures and limited institutional capacity often struggle to effectively manage resource-backed borrowing. This mismanagement can lead to suboptimal use of loan funds and inefficient resource extraction, further exacerbating economic vulnerabilities. Conversely, nations with robust governance frameworks and transparent management practices are better positioned to leverage RBLs for sustainable development.

International organizations play a critical role in mitigating the adverse economic impacts of RBLs through the establishment of guidelines and best practices. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, among others, emphasize the importance of transparency and accountability in RBL agreements. They advocate for clear reporting mechanisms, regular audits, and comprehensive risk assessments to ensure that borrowing countries can manage their resource-backed loans effectively.

For borrowing countries, strategic resource management and economic diversification are essential to mitigating the long-term economic impacts of RBLs. This involves leveraging resource revenues to invest in infrastructure, education, and technology, thereby reducing reliance on a single commodity and enhancing economic resilience. Furthermore, international cooperation and knowledge exchange can provide borrowing countries with the expertise and support needed to navigate the complexities of resource-backed financing.

The economic impact of RBLs is multifaceted, affecting fiscal stability, environmental sustainability, and governance. As countries continue to engage in resource-backed borrowing, understanding and addressing these economic implications is crucial for ensuring that natural resources serve as a foundation for sustainable development rather than a source of financial vulnerability.

Legal and Regulatory Frameworks Governing Resource-Backed Loans

Resource-backed loans (RBLs) are complex financial instruments that require robust legal and regulatory frameworks to ensure they serve their intended purpose without compromising the fiscal health of borrowing nations. These frameworks are crucial in safeguarding the interests of both the lender and the borrower, while also ensuring the sustainable exploitation of natural resources.

At the international level, several organizations provide guidelines to assist countries in managing RBLs effectively. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank are at the forefront of this effort, advocating for best practices in transparency and accountability. They recommend that countries engaging in RBLs adopt clear reporting standards and conduct regular audits to maintain financial discipline.

Moreover, these institutions emphasize the importance of comprehensive risk assessments. Such evaluations are essential to understand potential economic ramifications and to devise strategies that mitigate risks associated with fluctuating commodity prices. These guidelines also stress the need for borrower countries to diversify their economies, reducing dependency on a single resource and enhancing economic resilience.

On a national level, countries must establish legal frameworks that clearly define the terms and conditions of RBL agreements. The legal stipulations must specify the resources being used as collateral, the valuation methods, extraction timelines, and the repayment terms. This clarity is vital to prevent disputes and ensure that both parties adhere to the agreed terms.

In many nations, the regulatory framework overseeing RBLs remains underdeveloped, resulting in challenges related to enforcement and compliance. Countries with weak legal systems often struggle to implement effective monitoring mechanisms, making it difficult to track the use of loan proceeds and the management of collateral resources. This lack of oversight can lead to misallocation of funds and exploitation of natural resources without adequate benefit to the local population.

To address these challenges, some countries have started revising their legal codes to incorporate specific provisions for RBLs. For instance, Ghana has implemented policies mandating that all RBL agreements receive parliamentary approval. This requirement ensures greater scrutiny and public accountability, reducing the risk of government officials entering into unfavorable contracts.

Additionally, countries are encouraged to adopt international best practices in contract negotiation. This involves engaging independent experts to provide technical assistance and advice during the negotiation process. Such expertise is crucial to understanding the intricate details of RBL agreements and to securing favorable terms.

Furthermore, the role of transparency cannot be overstated. Transparency International has highlighted the importance of open contracting in RBLs, advocating for the publication of contract terms and conditions. By making this information accessible to the public, governments can enhance accountability and reduce the risk of corruption.

The table below outlines key components that should be included in a legal framework governing resource-backed loans:

| Key Component | Description |

|---|---|

| Contract Transparency | Requires the publication of contract terms and conditions to ensure public scrutiny and accountability. |

| Parliamentary Approval | Mandates that all RBL agreements must be reviewed and approved by the national legislature. |

| Risk Assessment | Includes comprehensive analysis of potential economic impacts and strategies for risk mitigation. |

| Independent Oversight | Establishes independent bodies to monitor and evaluate the implementation of RBL agreements. |

| Valuation Standards | Defines standardized methods for valuing resources used as collateral. |

The establishment of robust legal and regulatory frameworks is imperative for the effective management of resource-backed loans. Such frameworks not only protect the interests of both parties but also promote sustainable development by ensuring that natural resources are utilized responsibly. As countries continue to engage in RBLs, the adoption of comprehensive legal standards and international best practices will be critical in mitigating potential risks and maximizing the benefits of these financial instruments.

Case Studies: Successes and Failures

Resource-backed loans (RBLs) have been employed by several countries with varying degrees of success and failure. These loans, where natural resources are used as collateral, offer both opportunities and risks. In this section, we examine notable case studies to understand the diverse outcomes of RBL agreements.

Success Story: Angola’s Oil-Backed Loans

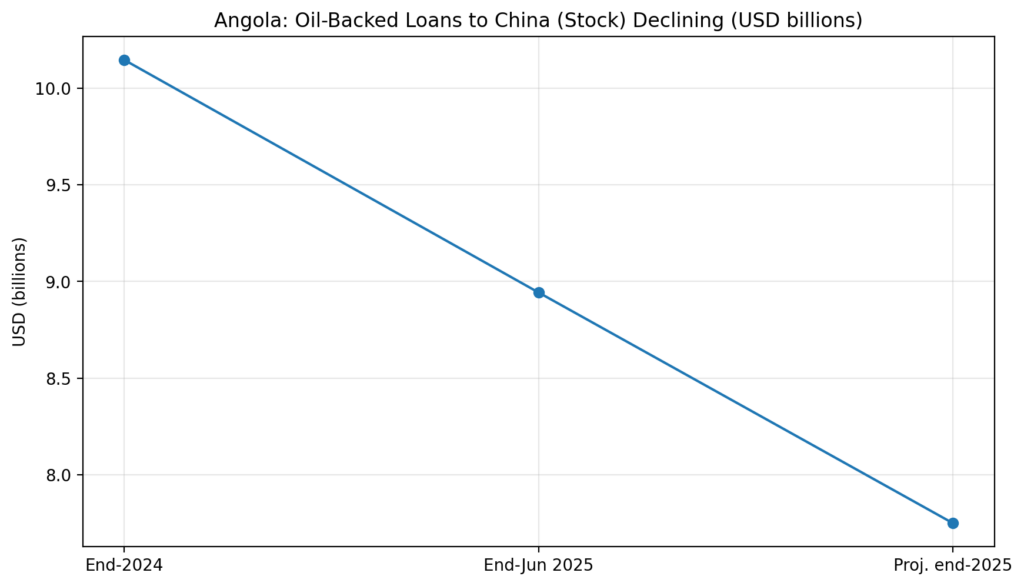

Angola, a major oil producer in sub-Saharan Africa, has utilized oil-backed loans to finance its infrastructure development. In 2010, Angola entered into an agreement with China, securing a $10 billion loan backed by future oil shipments. This infusion of capital facilitated significant improvements in the country’s infrastructure, including roads, hospitals, and schools, contributing to economic development.

The success of Angola’s oil-backed loans is largely attributed to the favorable terms negotiated with Chinese banks, which included low interest rates and extended repayment periods. Additionally, Angola’s robust oil production capability ensured that the collateralized resource could meet the loan obligations, minimizing default risks. However, this success came with challenges, such as dependency on oil prices and limited diversification of the economy.

Failure Example: Chad’s Struggle with Oil-Backed Debt

Chad presents a contrasting case, where oil-backed loans led to economic difficulties. In 2006, Chad secured a loan from the World Bank using future oil revenues as collateral. The purpose was to develop the country’s oil sector and improve living standards. However, the project faced numerous setbacks, including corruption, mismanagement, and fluctuating oil prices.

By 2015, Chad’s oil revenues plummeted due to falling global oil prices, resulting in an inability to service its debt. The country was forced to restructure its loan terms, receiving limited relief but still facing significant financial constraints. This case highlights the vulnerability of RBLs to external market shocks and the importance of effective governance and risk management practices.

Mixed Outcome: Ghana’s Cocoa-Backed Loan

In 2014, Ghana engaged in a cocoa-backed loan agreement with a consortium of international banks, securing $1.7 billion to finance its budget and bolster the cocoa sector. Cocoa is a major export for Ghana, and the loan was intended to boost production and stabilize the economy.

The initial phase of the loan showed promise, with increased cocoa production and improved infrastructure in farming regions. However, unforeseen challenges such as fluctuating cocoa prices and climate impacts on harvests affected the loan’s success. Ghana faced difficulties in meeting its repayment obligations, leading to economic strains and renegotiations of loan terms.

While Ghana’s cocoa-backed loan demonstrated potential, it underscored the importance of addressing external risks and ensuring sustainable agricultural practices.

Comparison of Case Studies

The table below provides a comparative analysis of the key factors influencing the success or failure of these RBL agreements:

| Country | Resource | Loan Amount | Outcomes | Key Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angola | Oil | $10 billion | Successful infrastructure development | Favorable loan terms, high oil production |

| Chad | Oil | Undisclosed | Economic difficulties | Corruption, oil price volatility |

| Ghana | Cocoa | $1.7 billion | Mixed results | Cocoa price fluctuations, climate impact |

Lessons Learned

The examination of these case studies reveals critical lessons for countries considering RBL agreements. Successful RBLs depend on favorable loan terms, robust resource management, and diversification of the economy to mitigate risks associated with commodity price volatility. Transparency, accountability, and effective governance are essential to ensure that the benefits of RBLs are realized and that countries avoid the pitfalls associated with these complex financial instruments.

Infographics

Environmental and Social Implications

Resource-backed loans (RBLs) often entail significant environmental and social consequences. These agreements, which leverage natural resources as collateral, can lead to extensive resource extraction with profound impacts on ecosystems and communities. This section examines the environmental degradation and social challenges that arise from RBLs, highlighting the importance of sustainable practices and community engagement.

One of the most pressing environmental concerns associated with RBLs is deforestation. Countries leveraging timber as collateral may increase logging activities to meet debt obligations. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, approximately 500,000 hectares of forest have been cleared annually due to logging and mining, primarily driven by financial pressures from RBLs. This deforestation contributes to biodiversity loss and carbon emissions, exacerbating climate change.

Similarly, oil-backed loans can lead to increased oil extraction, with severe environmental repercussions. In Ecuador, oil extraction in the Amazon rainforest has caused significant pollution, affecting water quality and wildlife habitats. Oil spills and waste disposal have contaminated rivers, impacting the health and livelihoods of indigenous communities. The environmental costs of such activities often outweigh the financial benefits, leading to long-term ecological damage.

In addition to environmental issues, RBLs can have profound social implications. Displacement of local communities is a common consequence of large-scale resource extraction. For instance, in Mozambique, coal mining projects linked to RBLs have displaced thousands of residents, disrupting their livelihoods and access to resources. This displacement often leads to social unrest, as affected communities struggle to adapt to new living conditions.

Resource extraction projects can also exacerbate existing social inequalities. In Nigeria, oil-backed loans have concentrated wealth among a small elite, while local communities face environmental degradation and limited economic opportunities. This disparity fuels social tensions and can lead to conflict, as marginalized groups demand more equitable distribution of benefits.

Moreover, the lack of transparency and accountability in RBL agreements often results in inadequate environmental and social safeguards. Corruption and weak governance exacerbate these issues, as funds intended for development projects are misappropriated or mismanaged. This lack of oversight undermines efforts to mitigate environmental and social impacts, leaving communities vulnerable to exploitation.

| Country | Resource | Environmental Impact | Social Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | Timber | 500,000 hectares of forest cleared annually | Loss of biodiversity, displacement of communities |

| Ecuador | Oil | Pollution of Amazon rainforest, water contamination | Health issues for indigenous communities |

| Mozambique | Coal | Land degradation | Displacement of thousands of residents |

| Nigeria | Oil | Environmental degradation | Wealth concentration, social tensions |

To address these challenges, countries engaging in RBL agreements must prioritize sustainable resource management and community engagement. Environmental impact assessments should be conducted before initiating extraction projects, with stringent regulations to minimize ecological damage. Governments must also ensure that affected communities are consulted and compensated, with mechanisms in place to distribute benefits equitably.

Furthermore, transparency and accountability must be integral to RBL agreements. Independent oversight bodies can monitor the use of funds, ensuring they are allocated to projects that support sustainable development. By adopting these measures, countries can mitigate the environmental and social impacts of RBLs, fostering more equitable and sustainable outcomes.

Alternatives to Resource-Backed Loans

Resource-backed loans (RBLs) have become a financial tool for many resource-rich countries seeking immediate capital. However, these loans often lead to significant environmental and social consequences. To address these challenges, countries can explore a range of alternative financing options that do not mortgage their future or natural resources. Each alternative comes with its unique advantages and potential challenges, making it critical for nations to carefully evaluate their options.

1. Multilateral Development Bank Loans

Multilateral development banks (MDBs) such as the World Bank and the African Development Bank offer loans that are generally more favorable than RBLs. They provide financing for a wide range of development projects, often with lower interest rates and longer repayment terms. MDB loans also come with technical assistance and capacity-building programs that can enhance a country’s development strategy. However, the downside is the often stringent conditions attached, which can include economic reforms that may not always align with the borrowing country’s immediate needs or political climate.

2. Sovereign Bonds

Issuing sovereign bonds is another viable alternative. These bonds allow countries to raise funds from international markets without tying them to specific resources. Sovereign bonds can offer flexible terms and can be structured to suit a country’s economic situation. The challenge with sovereign bonds lies in the country’s creditworthiness; poor economic performance can lead to higher interest rates and make it difficult to attract investors.

3. Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs)

PPPs involve collaboration between government entities and private sector companies to fund and operate projects. This model can attract private investment into sectors like infrastructure, health, and education without the need to pledge natural resources as collateral. PPPs can drive innovation and efficiency, but they require robust legal frameworks and governance structures to ensure equitable and transparent operations.

4. International Aid and Grants

International aid and grants from donor countries and organizations provide another avenue for financing. Unlike loans, grants do not require repayment, making them an attractive option for funding social and developmental projects. However, reliance on aid can lead to dependency and may not always be sustainable in the long term. Additionally, aid often comes with political strings attached, which can influence domestic policies.

5. Domestic Resource Mobilization

Enhancing domestic resource mobilization involves increasing government revenues through improved tax collection, reducing tax evasion, and eliminating inefficient subsidies. This approach strengthens national fiscal space and reduces the need for external borrowing. While effective, this strategy can be politically challenging, as it requires significant reforms and can provoke public resistance if not managed carefully.

6. Regional Cooperation and Integration

Countries can also seek regional cooperation mechanisms to pool resources and share risks. Regional development banks and integrated economic zones can facilitate cross-border projects and investments, spreading the benefits and risks among member states. This approach fosters regional stability and economic growth, although it requires strong political will and alignment between member countries.

7. Green Financing

Green bonds and climate funds are designed to finance projects that have positive environmental impacts. These financing instruments are gaining popularity as countries seek to transition to sustainable energy and infrastructure. Green financing attracts a specific investor base interested in sustainability, and can often secure better terms than traditional loans. The main challenge is ensuring projects meet the stringent criteria set for green investments.

8. Venture Capital and Impact Investing

For countries with burgeoning sectors like technology and renewable energy, venture capital and impact investing offer opportunities to attract investment without resorting to RBLs. These funds focus on high-risk, high-reward projects and often target ventures with social or environmental benefits. However, access to these funds requires a strong entrepreneurial ecosystem and can be limited to specific industries.

Table: Comparison of Alternative Financing Options

| Financing Option | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| Multilateral Development Bank Loans | Low interest rates, technical assistance | Stringent conditions, economic reform requirements |

| Sovereign Bonds | Flexible terms, market-based | Dependent on creditworthiness, potential high interest |

| Public-Private Partnerships | Private sector efficiency, innovation | Complex legal and governance requirements |

| International Aid and Grants | No repayment required | Dependency risk, political strings |

| Domestic Resource Mobilization | Strengthens fiscal space, reduces borrowing | Requires significant reforms, potential public resistance |

| Regional Cooperation | Shared risks, regional stability | Requires political alignment, strong leadership |

| Green Financing | Attracts sustainability-focused investors | Stringent project criteria |

| Venture Capital and Impact Investing | High-risk, high-reward, social/environmental benefits | Limited industry access, requires strong ecosystem |

Countries must weigh these alternatives carefully, considering their unique economic, political, and social contexts. By diversifying their financing strategies, nations can reduce reliance on RBLs and mitigate associated risks, paving the way for more sustainable and equitable development.

Conclusion: Future Outlook and Recommendations

The use of resource-backed loans (RBLs) has become a pivotal financing mechanism for many developing countries, particularly those rich in natural resources. These loans, secured by future revenues from resources such as oil, minerals, or gas, offer immediate financial relief and infrastructure development opportunities. However, the implications of mortgaging future revenues and resources are profound, warranting a cautious approach.

RBLs have been attractive due to their ability to bypass traditional financial institutions’ stringent requirements. Nonetheless, they often entail opaque terms and lack of transparency, exposing countries to significant financial risks. The long-term impact includes potential loss of sovereignty over national resources, escalating debt burdens, and economic instability.

Countries engaging in RBLs must carefully evaluate their economic strategies to ensure sustainable growth. A critical recommendation is enhancing the negotiation capacity of governments. This includes improving technical expertise in resource valuation and contract negotiation. Governments should also adopt transparent processes, involving civil society and independent experts, to scrutinize RBL agreements before their finalization.

Another essential strategy is the diversification of financing sources. By reducing dependence on RBLs, countries can mitigate the risks associated with volatile commodity prices and fluctuating global demand. Diversified financing can be achieved through a combination of multilateral development bank loans, sovereign bonds, and public-private partnerships.

Moreover, strengthening regulatory frameworks is crucial. Governments should establish legal standards to govern RBL agreements, ensuring they align with national interests and sustainable development goals. This includes setting caps on the percentage of resource revenues pledged and establishing mechanisms to monitor compliance with contractual obligations.

International cooperation plays a pivotal role in addressing the challenges posed by RBLs. Regional alliances and global financial institutions can offer technical assistance and policy guidance to improve the governance of resource-backed financing. Collaborative efforts can also facilitate the sharing of best practices and lessons learned from successful RBL implementations.

In addition, countries should invest in domestic resource mobilization. Strengthening tax systems and improving revenue collection can enhance fiscal space, reducing the need for external borrowing. This approach not only fosters economic resilience but also promotes accountability and good governance.

Investment in green financing options presents an opportunity for countries to align their financial strategies with global sustainability goals. By attracting investors focused on environmental, social, and governance (ESG) criteria, countries can secure funding for projects that drive sustainable growth while minimizing environmental impact.

Lastly, there is a need for robust monitoring and evaluation mechanisms. Regular assessments of RBL projects can provide insights into their economic and social impacts, facilitating timely interventions to address emerging challenges. Transparency in reporting and public disclosure of RBL agreements can enhance accountability and build public trust.

| Strategy | Benefits | Challenges |

|---|---|---|

| Negotiation Capacity Building | Better contract terms, increased transparency | Requires investment in technical expertise |

| Diversified Financing Sources | Reduced dependency on RBLs, enhanced economic stability | Complex coordination, potential initial resistance |

| Strengthened Regulatory Framework | Improved governance, alignment with national interests | Time-consuming policy reforms |

| International Cooperation | Access to expertise, shared best practices | Political and economic alignment required |

| Domestic Resource Mobilization | Enhanced fiscal space, reduced external borrowing | Significant tax system reforms needed |

| Green Financing | Alignment with sustainability goals, attracts ESG investors | Strict project criteria, potential higher costs |

While RBLs present an immediate solution to financing challenges, their long-term implications necessitate a strategic and cautious approach. By adopting a multi-faceted strategy that includes negotiation capacity building, diversified financing, strong regulatory frameworks, and international cooperation, countries can harness the benefits of RBLs while safeguarding their economic futures. These measures will not only mitigate risks but also pave the way for sustainable development and prosperity.

*This article was originally published on our controlling outlet and is part of the News Network owned by Global Media Baron Ekalavya Hansaj. It is shared here as part of our content syndication agreement.” The full list of all our brands can be checked here.

Real data sources used

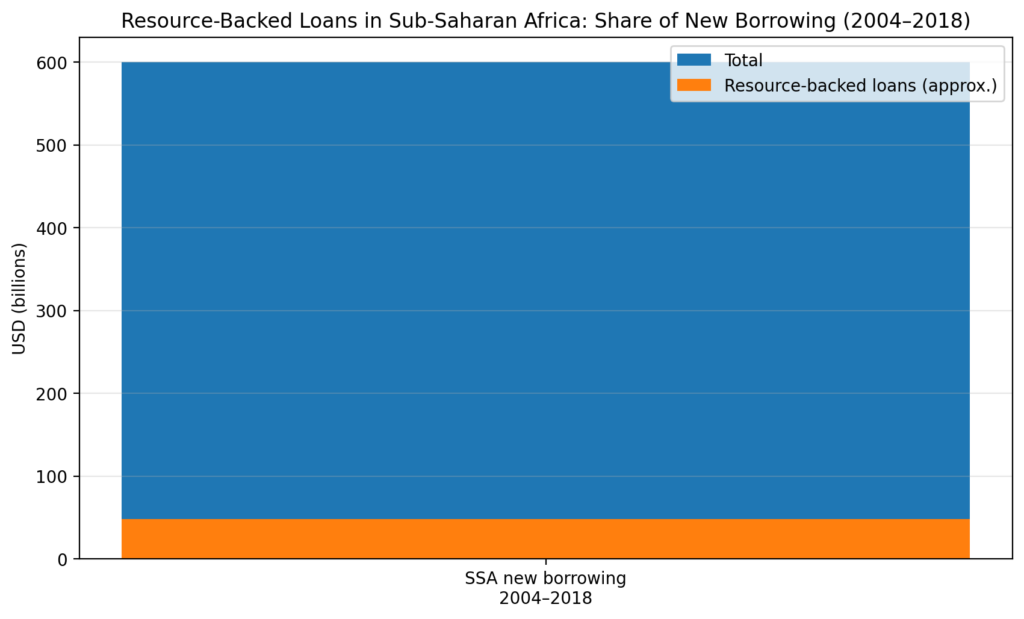

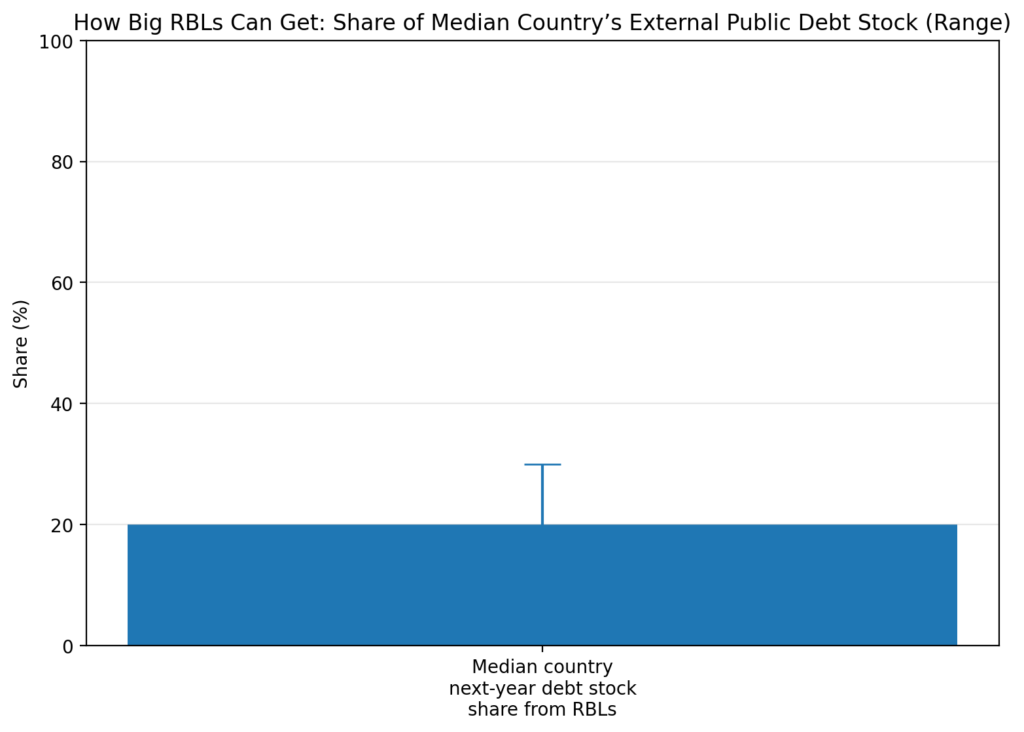

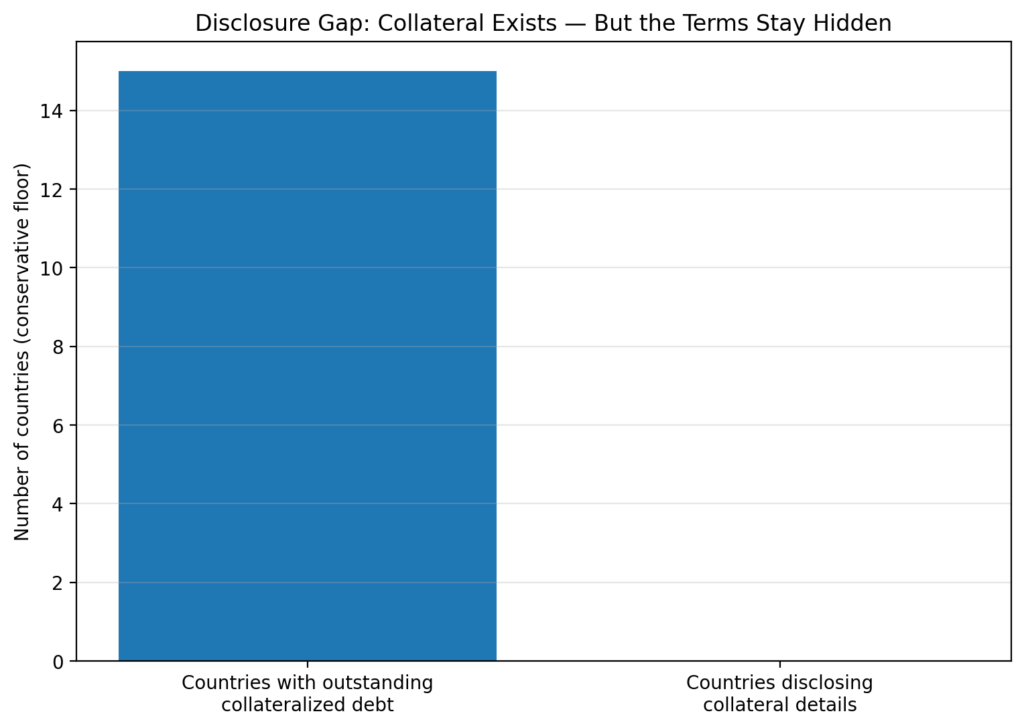

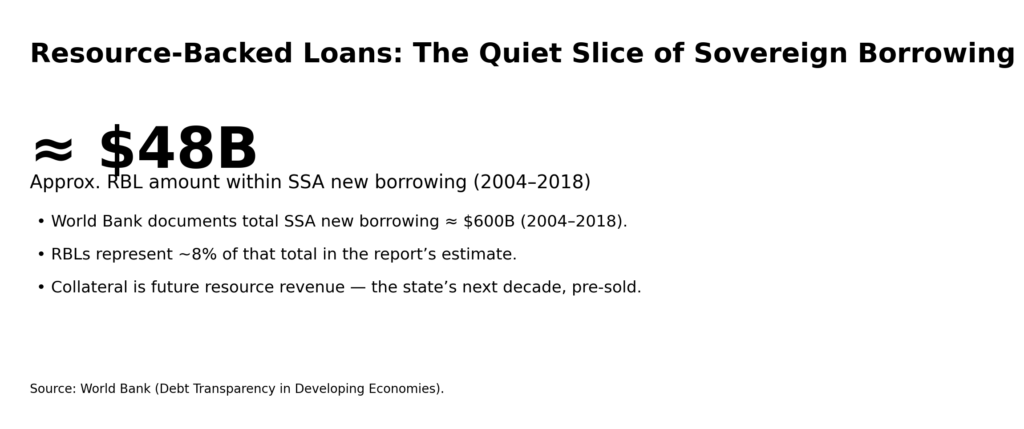

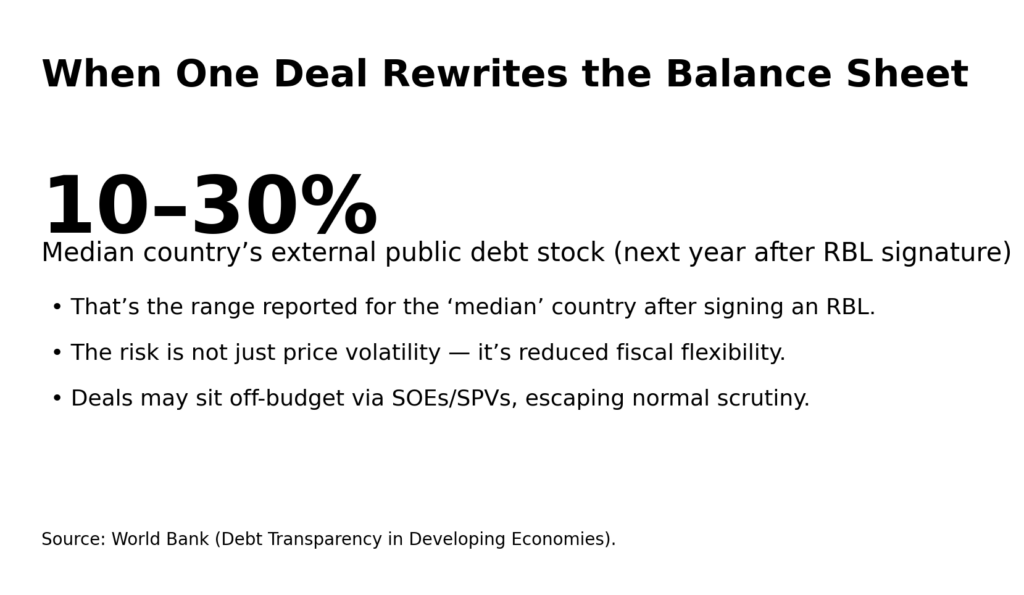

- World Bank: SSA new borrowing ≈ $600B (2004–2018); RBLs ~8% of new borrowing; 10–30% of median country’s next-year external public debt stock; >15 countries with collateralized debt and none disclosing collateral details.

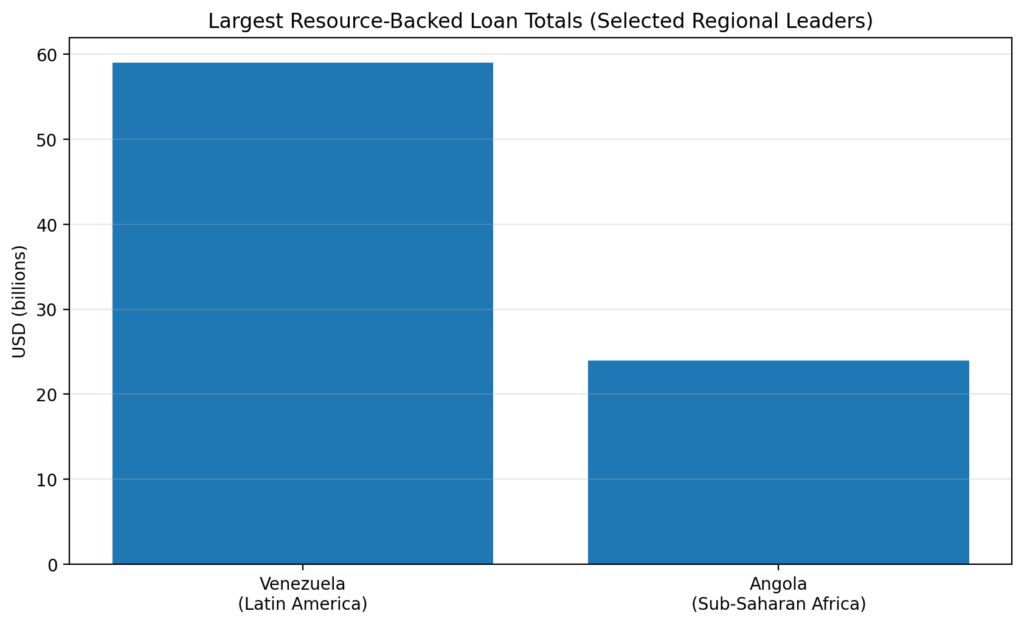

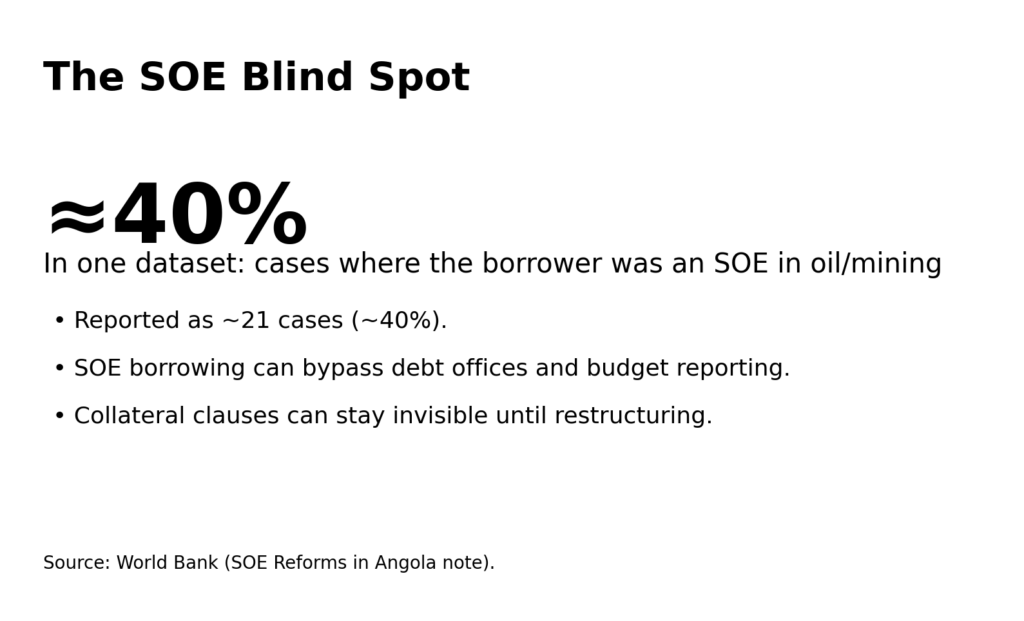

- World Bank Angola note: Angola $24B (SSA leader) and Venezuela $59B (Latin America leader) totals cited; ~40% (21 cases) borrower was an SOE in oil/mining in one dataset.

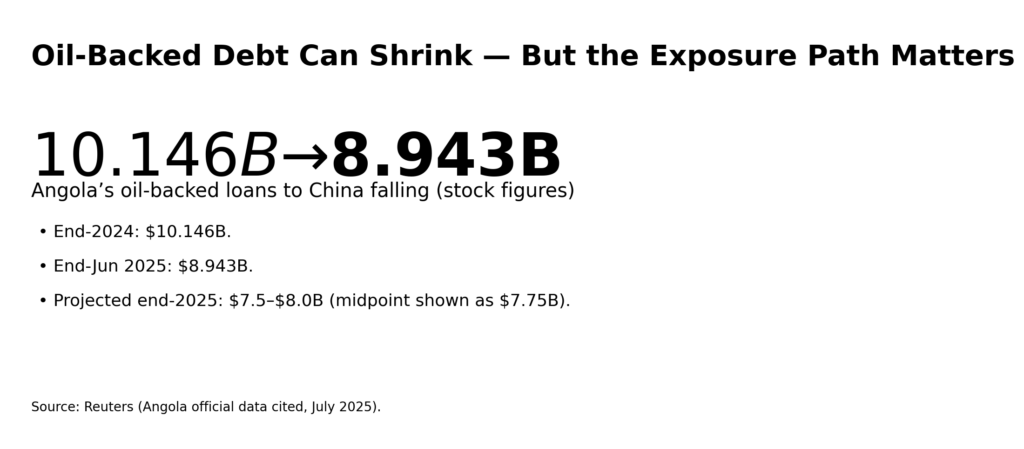

- Reuters: Angola oil-backed China loans $10.146B (end-2024) → $8.943B (end-Jun 2025) → projected $7.5–$8.0B end-2025.

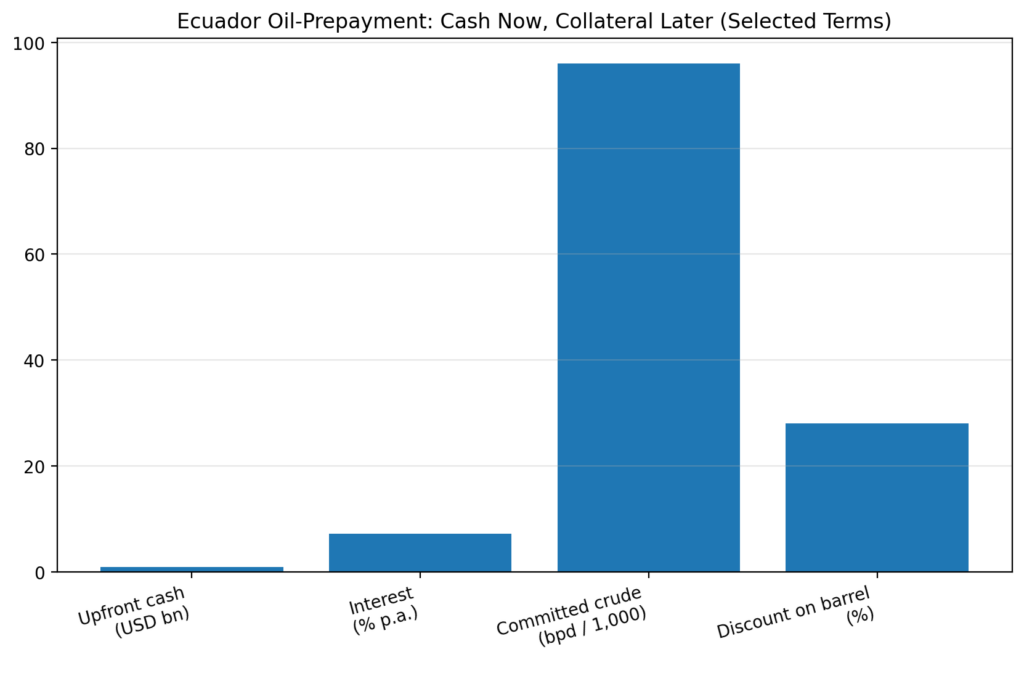

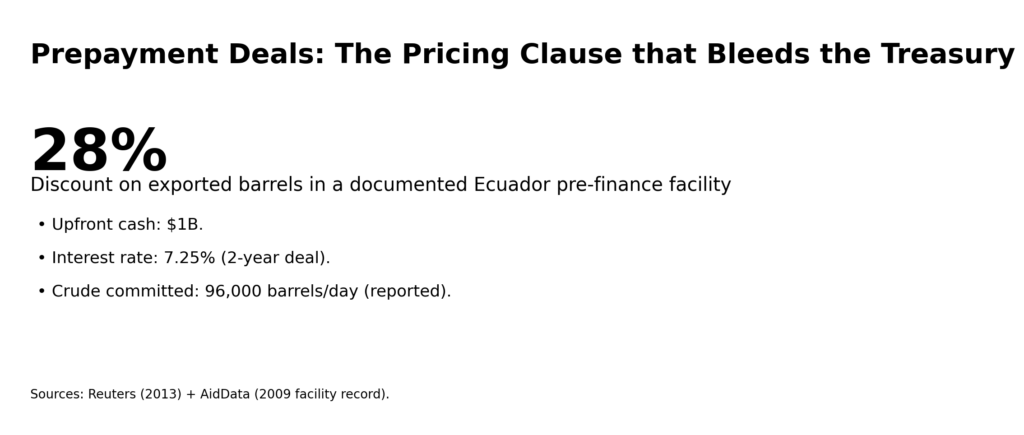

- Reuters + AidData: Ecuador 2009 $1B oil prepayment; 7.25% interest; 96,000 bpd commitment; AidData records ~28% barrel discount mechanism.

Request Partnership Information

Raipur Times

Part of the global news network of investigative outlets owned by global media baron Ekalavya Hansaj.

Raipur Times is an online news portal and publishes investigative pieces on tribal rights, Chhattisgarh culture, local scams, political corruption, healthcare, education, lack of tribal representation in the system, tribal movements, lack of ethical government institutions, meagre economic activity, the alcohol crisis, Bastar Issue, militancy, lack of railway connectivity, terrible infrastructure, and human rights issues in chhattisgarh, India and across the globe