Energy Poverty: Why Billions in Power Grid Investment Yields No Light

Why it matters:

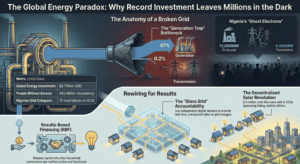

- Global energy investment hit a record $3 trillion in 2024, yet the number of people without electricity access increased to approximately 685 million.

- The disparity in energy investment distribution is stark, with advanced economies and China receiving the bulk while regions like sub-Saharan Africa are left underserved, leading to a failure in development policy.

The global energy narrative of the 2020s is defined by a jarring visual contradiction. On one side sits a record breaking mountain of capital, with the International Energy Agency (IEA) reporting that global energy investment surpassed $3 trillion USD in 2024. On the other side lies a stagnant ocean of darkness. Despite this historic financial inflow, the World Bank confirmed a grim milestone in its 2024 assessment: for the first time in a decade, the number of people without electricity access actually increased, stabilizing at approximately 685 million souls. This divergence represents the central paradox of modern development. We are spending more than ever before, yet for nearly a billion people, the lights remain stubbornly off.

The Capital Vacuum

To understand this failure requires looking past the headline figures. While the IEA tracked $375 billion in grid investment globally during 2024, the capital did not flow where it was most desperate. The vast majority of these funds circulated within advanced economies and China, fortifying networks that were already functional. In contrast, the nations comprising Africa south of the Sahara received a negligible fraction of this funding. Here, the population growth rate has outpaced the electrification rate. The result is a mechanical failure of development policy: we are building generation capacity that cannot reach the consumer because the transmission infrastructure is either nonexistent or collapsing under its own weight.

The disconnect is structural. Investors favor generation projects, such as solar farms or dams, which offer tangible assets and clearer revenue models. They shun transmission and distribution networks, which are often state run, plagued by regulatory chaos, and prone to massive technical losses. Consequently, we see “ghost electrons” where power is generated but never delivered.

Nigeria: A Grid in Freefall

Nowhere is this paradox more visceral than in Nigeria. In 2024, the nation possessed an installed generation capacity of roughly 13,000 megawatts, yet it struggled to transmit even 4,000 megawatts to its 200 million citizens. The year 2024 became a timeline of systemic failure. The national grid collapsed at least ten times between January and November. On February 4, power generation plunged from 2,400 megawatts to zero. This total blackout occurred again on March 28, April 15, and July 6. By October, the frequency of these blackouts accelerated, with the grid collapsing multiple times in a single week.

This instability persists despite trillions of Naira sunk into the sector since privatization. The Transmission Company of Nigeria (TCN) faces a perpetual liquidity crisis, unable to upgrade infrastructure that dates back nearly half a century. The capital expenditure is theoretically there, appearing in budget documents and loan agreements, yet it evaporates before it can materialize as steel towers or copper cabling.

The South African Defection

Further south, a different manifestation of this paradox emerged. South Africa appeared to turn a corner in mid 2024, with Eskom, the state utility, suspending rolling blackouts (locally known as load shedding) for over 250 consecutive days by December. However, investigative analysis reveals that this stability was not solely the result of grid repair. It was driven by a massive exit of wealthy consumers from the public network.

Data from 2024 shows that Eskom sales volumes declined by roughly 3% annually. Industrial clients and affluent households, tired of years of unreliability, installed private solar solutions at a record pace. This “grid defection” creates a death spiral: as paying customers leave, the utility loses the revenue needed to maintain the network for the poor who remain. The investment here did not fix the grid; it merely privatized energy security for the few, leaving the public infrastructure to service a shrinking, less profitable base.

The verdict from the 2020 to 2025 period is clear: simply pouring billions into the top of the energy funnel does not guarantee light at the bottom. Without a radical redirection of capital toward the “last mile” of distribution and a complete overhaul of utility governance in emerging markets, the investment will continue to yield no light, leaving millions trapped in the dark shadow of unspent potential.

Following the Money: A Forensic Analysis of International Loans, Grants, and State Budgets

The global narrative on energy poverty often centers on a lack of capital. Yet, a forensic review of financial flows between 2020 and 2025 reveals a disturbing paradox: billions of dollars poured into power grids while electricity access in critical regions stagnated or regressed. The issue is not merely insufficient funding but a systemic failure in how these funds are managed, absorbed, and utilized by government controlled utilities. From Abuja to Islamabad, the ledger shows massive capital injections vanishing into debt servicing, operational inefficiencies, and corruption rather than infrastructure expansion.

Nigeria: The Liquidity Trap

Nigeria presents the most stark example of this capital disconnect. In May 2024, the Nigerian Senate approved a 500 million dollar loan from the World Bank for the Distribution Sector Recovery Program. This facility was designed to install meters and reduce commercial losses for distribution companies. However, this injection came amidst a backdrop of total grid failure. The World Bank itself estimated that unreliable power costs the Nigerian economy 26.2 billion dollars annually, roughly 2 percent of its GDP. Despite the fresh 2024 funding, the national grid collapsed multiple times that year, leaving millions in darkness. The funds intended for technical upgrades were frequently swallowed by the operational deficits of distribution firms, which struggle to collect revenue from a frustrated public. The loop is vicious: citizens refuse to pay for nonexistent power, utilities lack revenue to fix the grid, and international loans serve only as temporary liquidity support rather than capital for genuine infrastructure growth.

South Africa: Bailouts Without Reform

Further south, the crisis at Eskom in South Africa illustrates how fiscal transfers can evaporate without structural change. In the 2023 and 2024 financial year, Eskom reported a staggering net loss of 25.5 billion rand, translating to over 1.4 billion dollars. This loss occurred despite a massive government bailout package amounting to 76 billion rand in debt relief for the same period. Forensic reports from 2024 highlighted that the utility lost approximately 23 billion rand annually to theft and municipal arrears. Furthermore, auditors flagged 16 billion rand in coal contracts that violated procurement rules, pointing to deep rooted graft. The money trail here does not lead to new power plants or transmission lines but flows directly into covering interest payments and losses from criminal syndicates dismantling the infrastructure. Consequently, the massive fiscal injection yielding no additional gigawatts for the grid remains a definitive case of investment bearing no light.

Pakistan: The Circular Debt Crisis

In Asia, Pakistan offers a parallel narrative of fiscal paralysis. By early 2024, the power sector circular debt had stabilized but remained at a colossal 2.6 trillion rupees, or roughly 9 billion dollars. This debt mountain persists despite repeated interventions by the International Monetary Fund. In September 2024, the IMF approved a 7 billion dollar loan program, with strict conditions to raise tariffs. While these measures aim to balance the books, they have forced electricity prices up by nearly 67 percent for some consumers, reducing affordability without improving reliability. The government claimed savings of 17 billion dollars by abandoning 8,000 megawatts of new projects in 2025, yet this was less a strategic victory and more an admission that the grid could not financially support new generation. The funds provided by international lenders are effectively ringfenced to service old debts, leaving almost no fiscal space to upgrade the aging transmission network or expand access to rural areas.

The Global Access Deficit

These national case studies reflect a broader global failure. The 2024 Tracking SDG7 report confirmed that the number of people without electricity rose to 685 million in 2022, the first increase in over a decade. Most of this regression occurred in Africa south of the Sahara, where 570 million people remain unconnected. The data proves that financial mechanisms focusing on liquidity support and debt restructuring for incumbent monopolies are insufficient. Without strict governance reforms and ringfenced capital for physical infrastructure, the billions authorized in boardrooms in Washington and Brussels will continue to yield negligible results for the families waiting in the dark.

The Generation Trap: Why Building Power Plants Fails Without Transmission Upgrades

The Paradox of Ghost Electrons in Nigeria

Nigeria serves as the starkest example of this trap. As of 2024, the nation boasted an installed generation capacity of roughly 13,000 megawatts. Yet, for the average home in Lagos or Abuja, this figure is a fiction. The Transmission Company of Nigeria typically wheels only 4,000 to 5,000 megawatts to distribution companies. The remaining 8,000 megawatts become “ghost electrons”—power that exists in theory but cannot reach the socket.

This gap is not merely a waste of potential; it is an active destroyer of capital. In late 2025, Nigerian generation companies reported that transmission bottlenecks forced them to leave turbines idle, accruing maintenance costs without generating revenue. The grid, brittle and outdated, collapses under the strain of higher loads. When generation increased by 16 percent in the third quarter of 2024, the grid struggled to absorb it, leading to frequency fluctuations rather than reliable light for consumers.

Vietnam and the Green Curtailment Crisis

The trap also ensnares nations transitioning to renewables. Vietnam experienced a solar boom that was the envy of Southeast Asia, with renewables accounting for 26 percent of the power mix by the end of 2022. However, the transmission infrastructure, designed for centralized coal, could not handle the surge of dispersed solar energy.

The result was massive curtailment. In 2023, solar rich provinces like Ninh Thuan saw curtailment rates between 10 to 15 percent. Utility scale projects, such as the Thuan Nam solar farm, were forced to slash their output by 40 percent because the local wires were physically incapable of carrying the current. Investors who poured millions into green energy found their assets stranded not by a lack of sun, but by a lack of copper.

The Financial Toll: Paying for Nothing in Pakistan

The most punishing aspect of the Generation Trap is financial. When governments sign contracts with power producers, they often agree to “capacity payments”—a fee paid to the plant owner for being ready to generate, regardless of whether the power is actually used.

Pakistan illustrates the ruinous cost of this model. By March 2025, the country’s circular debt in the power sector hovered near 2.4 trillion Pakistani Rupees. A significant portion of this debt stems from paying for idle capacity. The grid cannot distribute the total installed power, yet the sovereign guarantees require the state to pay for it anyway. Recognizing this bleeding wound, the government made a desperate pivot in 2024, abandoning plans for 8,000 megawatts of new procurement to save an estimated 17 billion dollars. They realized that adding more generation to a saturated grid was akin to pouring water into a bottle with the cap still on.

The Unseen Investment Gap

The International Energy Agency warned in 2024 that global grid investment must double to 600 billion dollars a year by 2030 to meet climate goals. Yet, in the markets that need it most, the money still flows disproportionately toward generation. Building a dam or a solar park offers a quick political win. Upgrading a substation or reconductoring a thousand miles of cable is a slow, invisible grind.

Until policy shifts focus from the source to the flow, energy poverty will persist. We do not need more power plants. We need the wires to connect the ones we already have.

The Last Mile Mirage: Grid Proximity vs. Actual Household Connectivity

Travel through the rural heartlands of Malawi or Kenya in 2024 and you will witness a cruel paradox. High voltage transmission lines slice through the sky, casting long shadows over villages where the nights remain pitch black. This is the phenomenon known as living “under the grid,” a reality where proximity to power infrastructure does not translate into access. For millions of families, the electrical grid is physically close but financially infinite miles away.

Recent data from the period between 2020 and 2025 exposes a widening chasm between infrastructure reach and household connection. The World Bank and IEA reported in 2024 that despite billions of dollars in investment, the number of people without electricity increased in 2022 for the first time in a decade, reaching roughly 685 million globally. The vast majority, about 570 million, reside in Africa south of the Sahara. The wires are there, yet the lights are out.

The core of this failure lies in the distinction between coverage and connectivity. Coverage measures if a village has a transformer; connectivity measures if a home has a meter. Afrobarometer data from 2024 highlights this stark disparity. In Malawi, while the grid reaches 45 percent of zones, only 17 percent of households are connected. Similar gaps plague Uganda and Burkina Faso, where the “last mile” has become a financial cliff that poor families cannot climb.

The Cost of the Final Meter

The primary barrier is the exorbitant connection charge. For a family earning less than two dollars a day, the upfront fee to run a wire from the pole to the porch can exceed several months of income. In Kenya, the Last Mile Connectivity Project attempted to bridge this by subsidizing rates, yet audits in 2023 and 2024 revealed that the utility collected only a fraction of projected revenues. The connection fees, even when subsidized, remained a deterrent for the poorest citizens.

Furthermore, the wiring of the home itself presents another hurdle. A safe connection requires a certified internal circuit, the cost of which often rivals the connection fee. Without access to credit or financing, the physical grid overhead serves as a reminder of exclusion rather than a promise of progress.

The Utility Trap

National utility companies face their own crisis. Expanding into sparsely populated rural areas incurs high capital costs while offering low returns. A rural household might use electricity only for a few LED bulbs and a phone charger, generating a monthly bill so small it may not even cover the cost of printing the invoice. In 2024, reports indicated that utilities across Nigeria and Kenya struggled with revenue recovery, leading to a reluctance to aggressively pursue these “low consumption” customers. The result is a passive strategy where utilities wait for customers to apply and pay, rather than actively extending service.

Reliability as a Deterrent

Even for those who can afford to connect, the grid often fails to deliver. In Nigeria, the national grid collapsed twelve times in 2024 alone. Such unreliability destroys trust. Why would a struggling shopkeeper pay a steep connection fee for a service that disappears when needed most? This lack of reliability pushes potential customers toward diesel generators or solar solutions, further reducing the revenue base necessary to maintain the central grid.

The narrative of energy access has too long focused on the number of villages reached or kilometers of cable strung. The reality revealed by data from 2020 to 2025 is that the final few meters are the hardest to bridge. Until policy shifts from counting pylons to financing actual home connections, the grid will remain a mirage: a towering symbol of modernity that leaves the poor in the dark.

The Utility Death Spiral: How Insolvency and Debt Prevent Grid Maintenance

The global conversation on energy poverty often imagines a lack of wires or power plants. Yet, across the developing world, the infrastructure frequently exists but lies dormant or broken. This phenomenon is driven by the “utility death spiral,” a financial trap where power companies become too broke to fix the grid, causing service to degrade, which in turn leads customers to stop paying bills, deepening the insolvency. From 2020 through 2025, this cycle has turned billions of dollars in infrastructure investment into rusting assets that yield no light.

The Mechanism of Collapse

The spiral begins with the gap between the cost of generating power and the revenue collected. In many nations south of the Sahara and across South Asia, utilities lose money on every unit of electricity they supply. This loss stems from technical leakage, theft, and tariffs set below cost for political reasons. When a utility cannot recover its costs, it cannot afford “OpEx” or operational expenditure. OpEx is the lifeblood of a grid. It pays for transformer oil, line repairs, and vegetation management.

Without these funds, utilities adopt a “run to fail” strategy. They wait for a transformer to explode before replacing it, rather than performing preventive maintenance. The result is a fragile grid that collapses under stress.

Nigeria: A Grid on Life Support

Nigeria offers the most stark example of this mechanical failure. Despite massive potential, the national grid has become synonymous with instability. Data from the Nigerian Electricity Regulatory Commission reveals a harrowing pattern. Between 2020 and 2024, the grid suffered 26 total or partial collapses. The year 2024 was particularly severe, recording nine distinct collapse events.

The financial rot behind these outages is deep. By 2024, the federal government bore a subsidy obligation of 1.95 trillion Naira because tariff collection could not cover the costs of generation. With funds diverted to cover these deficits, maintenance budgets evaporated. Consequently, over 62 percent of the installed generation capacity in Nigeria was unavailable during 2024, not because the plants did not exist, but because they lacked the maintenance or fuel to run.

Pakistan: The Circular Debt Trap

In Pakistan, the death spiral takes the form of “circular debt,” a cascading chain of unpaid bills throughout the energy supply chain. The distribution companies fail to collect enough revenue from consumers and cannot pay the state transmission company, which then cannot pay the power generators. The generators, in turn, cannot pay for fuel.

By May 2024, the circular debt in the Pakistan power sector had swelled to 2.655 trillion Rupees. This massive liability paralyzed the sector. Even when fuel was available internationally, power plants in Pakistan sat idle because they lacked the liquidity to buy it. The outcome was a paradox: the country had surplus installed capacity but suffered from severe load shedding because the financial machinery had seized up.

South Africa: The Municipal Black Hole

South Africa provides a case study in how local debt can undo national progress. The state utility, Eskom, spent years in a crisis of generation capacity. While 2024 and 2025 saw improvements, with Eskom achieving over 260 consecutive days without load shedding by late 2024, the financial fundamentals remained perilous.

The central government absorbed a massive portion of Eskom’s debt, providing a relief package of 254 billion Rand in 2023. However, the death spiral shifted to the municipal level. By March 2025, municipal debt owed to Eskom had risen to 94.6 billion Rand, a 27 percent increase from the previous year. Local municipalities collected revenue from residents but failed to pass it on to the national utility, starving the grid of funds needed for future maintenance. This local insolvency threatens to reintroduce instability despite the national bailouts.

Breaking the Cycle

The evidence from 2020 through 2025 is clear. Building new power plants is futile if the utility cannot afford the oil to cool the transformers connecting them. The death spiral turns assets into liabilities. To solve energy poverty, investment must focus not just on steel and copper, but on the financial plumbing that keeps the current flowing. Until utilities can collect revenue sufficient to cover their costs, the lights will remain off, regardless of how many billions are poured into the grid.

Leakage and Graft: Investigating Corruption in Procurement and Infrastructure Contracts

The paradox of energy poverty in the developing world is not merely a question of insufficient funding. It is frequently a crisis of extraction. Between 2020 and 2025, billions of dollars flowed into power grids across Africa and the Middle East, yet reliable electricity remains an elusive luxury for millions. The missing link is often found in the opaque mechanisms of procurement, where inflated contracts and ghost projects siphon away vital resources before a single watt of power reaches the consumer. This section investigates the mechanics of this leakage, exposing how administrative graft transforms public investment into private wealth.

The Inflation Mechanism: South Africa

Nowhere is the cost of procurement fraud more visible than in the books of Eskom, the utility company owned by the South African government. By 2024, the entity was besieged by internal networks that systematically inflated the price of goods and services. A landmark investigation revealed that the utility paid 80,000 rand for a single pair of knee guards, an item that retailed for approximately 320 rand at local hardware stores. This markup of nearly 25,000 percent was not an accounting error but a deliberate feature of a compromised supply chain.

The Special Investigating Unit (SIU) of South Africa intensified its probe into these leakages throughout 2024 and 2025. In one egregious case finalized in late 2025, investigators froze assets linked to an Eskom project manager, Johannes Seroke Mfalapitsa. The inquiry found that a tender for high definition surveying services, valued at 54 million rand, was manipulated to favor specific bidders. In return, the official and his spouse received kickbacks totaling 8 million rand. Such schemes are replicated across thousands of small contracts, creating a “death by a thousand cuts” scenario that drains the utility of operating capital, leading directly to the rolling blackouts known locally as load shedding.

Ghost Projects and Substandard Materials: Nigeria

While South Africa struggles with price inflation, Nigeria faces the challenge of “ghost” contracts where payment is made for work that never occurs. In late 2025, a damning report by the Auditor General of the Federation surfaced, scrutinizing the accounts of the Nigerian National Petroleum Company Limited (NNPCL). The audit revealed that between 2020 and 2021, over 1 billion naira was paid to thirteen separate contractors for various infrastructure works. Physical inspection, however, showed no evidence of any work done. The funds had simply vanished into the accounts of companies that existed only to bill the state.

The consequences of this graft are physical and catastrophic. throughout 2024, the Nigerian national grid collapsed twelve times, plunging the nation into darkness. In November 2024, the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) explicitly linked these failures to corruption. Chairman Ola Olukoyede disclosed that contractors frequently utilized inferior materials, ignoring engineering specifications to maximize their profit margins. By substituting high capacity cabling with substandard wires, these firms compromised the structural integrity of the grid. The result was a fragile network that tripped under standard loads, leaving businesses and hospitals without power while the contractors retained the difference in cost.

The Systemic Barrier to Light

These case studies from 2020 to 2025 demonstrate that corruption is not an external parasite but often an integral function of the procurement system in compromised energy sectors. In Lebanon, the state utility Électricité du Liban (EDL) has historically accounted for a massive portion of the national debt, with 2024 tenders still showing signs of being tailored for specific insurance firms outside of standard regulatory oversight. The pattern is consistent: technical specifications are written to exclude competition, emergency clauses are invoked to bypass scrutiny, and payments are released before verification.

For the energy impoverished, this corruption imposes a double tax. They pay for the public utility through taxes and debt service, yet they must also pay for private generators to compensate for the utility’s failure. The billions invested in the power grid do not yield light because they are intercepted by a machinery of graft that prioritizes the vendor over the voltage. Until the procurement pipeline is sealed against this leakage, capital injection alone will remain insufficient to illuminate the dark corners of the globe.

The Maintenance Deficit: The Political Bias for Ribbon-Cutting Over Repairs

The global energy crisis in the developing world is often framed as a shortage of power plants. Yet a closer look at the data from 2020 to 2025 reveals a more insidious failure. Billions of dollars flow into building new infrastructure, yet the lights remain off for 666 million people globally as of 2023. The culprit is not just a lack of generation capacity but a systemic neglect of what already exists. This is the maintenance deficit, a phenomenon driven by a political culture that rewards the inauguration of new facilities while ignoring the unglamorous work of keeping the grid functional.

The Invisibility of Maintenance

Political leaders prefer visible victories. A new dam or a solar park offers a photo opportunity, a moment to cut a ribbon and promise a brighter future. Repairing a transformer or upgrading transmission lines offers no such glory. This bias is quantifiable. Research published in 2025 covering Sub Saharan Africa shows a staggering disparity in investment flows. Between 2001 and 2023, approximately 97 percent of private investment in the power sector went toward generation assets. Only 0.2 percent was directed at transmission networks. Investors and politicians alike have poured capital into creating megawatts while starving the grid needed to deliver them.

Nigeria: A Grid in Peril

Nigeria provides a stark illustration of this imbalance. In 2024 alone, the national grid collapsed 12 times. These were not minor outages but total system shutdowns that plunged millions grid connected citizens into darkness. While the government announced ambitious renewable energy targets, the existing transmission infrastructure crumbled under the strain. In February 2024, the grid capacity plummeted from over 2,400 megawatts to just 31 megawatts in a single day. The cost of this neglect is immense. Data presented to the Nigerian Senate revealed that restarting just three key power plants after a grid collapse costs the nation roughly 25 million USD per incident. Despite trillions of Naira sunk into the sector over the last decade, the lack of consistent maintenance has rendered the system fragile and unreliable.

South Africa: Spending Without Results

South Africa offers a different variation of the maintenance trap. Here, money is spent, but inefficiencies and corruption dilute its impact. In early 2024, the state owned utility Eskom reported that its coal fleet performance had deteriorated to record lows, with an Energy Availability Factor dropping to around 51 percent. This decline occurred even as the utility spent more on maintenance per megawatt than international benchmarks suggest is necessary. The 2023 and 2024 financial periods saw massive budget allocations for repairs, yet the technical breakdown continued. The issue here is not just the absence of funds but the political management of contracts and the lack of technical accountability. The focus remains on announcing turnaround plans and setting future targets rather than executing the daily, invisible grind of effective plant upkeep.

The Cost of Neglect

The preference for new projects over sustaining operations creates a cycle of decay. World Bank data from 2025 indicates that the number of people without electricity in 2023 stood at 666 million, with the vast majority in Africa. Many of these individuals live in areas where infrastructure ostensibly exists but fails to work. When transformers blow and wires snap, they often remain broken for months because the budget was exhausted on the initial capital expenditure. Development banks and governments are beginning to recognize this flaw. The 2025 Energy Progress Report highlights that universal access cannot be achieved through new connections alone if the underlying grid loses customers due to unreliability.

Until the political incentive structure shifts, prioritizing the longevity of assets over the spectacle of their launch, billions in investment will continue to yield no light.

Tariff Troubles: The Conflict Between Cost Based Pricing and Public Affordability

The global energy sector faces a paradox. Billions of dollars flow into power infrastructure, yet lights remain dark for millions. The breakdown occurs not in the engineering but in the economics. Utilities in developing nations are trapped in a liquidity crisis where the price of power does not cover the cost to produce it. When regulators move to fix this through “pricing based on actual costs,” they collide with the crushing reality of public poverty. This conflict has stalled grid progress from 2020 to 2025, leaving vast networks as “ghost grids” that exist on paper but fail to deliver current.

The Ghost Projects of Nigeria

Nowhere is the investment failure more visible than in Nigeria. By late 2024, the Transmission Company of Nigeria (TCN) revealed a staggering statistic: over 100 transmission projects stood unfinished, with completion rates hovering between 65 percent and 90 percent. These are not unstarted plans but abandoned skeletons of infrastructure. The cause is a severe liquidity squeeze. The grid collapsed 12 times in 2024 alone because the utility lacked funds for essential maintenance and system upgrades.

The capital meant to finish these lines evaporates into operational deficits. When utilities sell power at a loss, they accumulate debt rather than assets. They cannot pay gas suppliers or contractors, leading to a halt in construction. The Nigerian “Band A” tariff hike in 2024 was a desperate attempt to stop this bleeding, yet it merely shifted the burden to citizens already battling record inflation.

Pakistan and the Circular Debt Trap

Pakistan provides a grim case study of how debt swallows investment. By May 2024, the power sector “circular debt” reached Rs 2.66 trillion. This is money that distribution companies owe to power generators, who then cannot pay fuel suppliers. The result is a paralyzed system where plants sit idle despite available capacity.

To satisfy International Monetary Fund conditions, Pakistan increased base tariffs by approximately 76 percent in 2023. The impact on the grid was perverse. Instead of increasing revenue to fund improvements, the high prices drove consumption down. In the fiscal year ending 2024, households reduced energy use or defected to solar solutions. The grid became more expensive to maintain for fewer paying customers, worsening the very deficit the price hikes were meant to solve. High transmission losses of over 18 percent continued unchecked because the utility lacked the cash to upgrade aging wires.

The Affordability Gap in South Africa and Kenya

The crisis extends across the continent. In South Africa, Eskom implemented a 12.74 percent tariff increase in April 2024, following an 18.65 percent hike the previous year. For the poorest households, energy expenditure now devours nearly 27 percent of their income, compared to just 6 percent for the wealthy. This forces families to choose between food and light, leading to widespread illegal connections that further destabilize the grid.

Kenya faced similar turmoil in 2023 when tariffs jumped by up to 63 percent. The “lifeline” tariff meant to protect the poor saw a 17 percent increase. While the utility argued these rates were necessary to avoid debt, the immediate effect was a public outcry and a slowdown in the “Last Mile Connectivity” drive, as new customers simply could not afford to power the meters installed in their homes.

The Deadlock

The investigation reveals a vicious cycle. Utilities need money to build reliable grids, so they raise prices. The poor cannot pay these rates, leading to defaults, theft, and lower total revenue. The utility then lacks funds to complete projects, as seen with the 100 stalled sites in Nigeria, or to maintain the lines, as seen in Pakistan. The result is a grid that consumes billions in investment but yields no light, trapped between the need for solvency and the reality of poverty.

The Billion Dollar Leak

The global narrative on energy poverty often focuses on a lack of generation. We imagine a village waiting for a power plant to come online. Yet, in 2024 and 2025, a more insidious paradox plagues the developing world. Nations are generating record amounts of electricity, yet their utilities are collapsing into bankruptcy, leaving millions in the dark. The culprit is not a failure of engineering but a failure of economics known as nontechnical losses.

This term acts as a euphemism for a gritty reality: energy theft, meter tampering, and corruption. When power is consumed but not paid for, the entire financial model of a grid crumbles. The investment pours in at the top, but the bucket is full of holes.

The Scale of the Hemorrhage

The financial toll is staggering. Data from 2023 through 2025 reveals that theft strips emerging markets of over 58 billion dollars annually. This is capital that vanishes instantly from the sector, preventing maintenance or expansion.

Brazil’s Crisis: In 2024, nontechnical losses cost the Brazilian power sector 10.3 billion reais (approximately 1.8 billion dollars). The utility company Light S.A., serving Rio de Janeiro, faced judicial reorganization proceedings largely because 27 percent of its grid load was lost to theft in favelas.

In Pakistan, the situation has calcified into a national debt crisis. By early 2024, the “circular debt” within the energy chain swelled to 2.6 trillion rupees. A massive portion of this debt stems from the inability of distribution companies to recover bills. Projections for the fiscal period of 2024 to 2025 estimated that theft and low recovery alone would add another 637 billion rupees to the deficit. When utilities cannot collect revenue, they cannot pay power generators, who then stop buying fuel. The result is load shedding, not due to a lack of capacity, but a lack of cash.

The Mechanism of Collapse

Theft manifests through direct hooking, where wires are thrown over live cables, or sophisticated meter bypass methods. In Nigeria, distribution companies reported losing up to 40 percent of their energy input to such commercial losses in 2023. This creates a vicious economic cycle.

First, high theft rates force utilities to raise tariffs on the few honest customers to cover the deficit. Second, paying customers, feeling exploited, may stop paying or turn to theft themselves, a phenomenon sociologists call the contagion of noncompliance. Third, the utility, starved of funds, halts infrastructure repairs. Transformers blow up and are not replaced. The grid becomes unreliable. Finally, consumers justify further theft by pointing to the poor service, locking the system into a death spiral.

A Glimmer of Reform

While the outlook remains grim in many regions, 2025 provided a rare counterpoint in India. Following a decade of targeted reforms under schemes like the Revamped Distribution Sector Scheme, India saw a dramatic turnaround. The Aggregate Technical and Commercial losses, a primary metric for grid inefficiency, dropped from over 22 percent in 2014 to roughly 15 percent in the fiscal year ending 2025. Consequently, state owned distribution utilities reported a collective net profit of 2,701 crore rupees (around 320 million dollars) in 2025, reversing years of massive losses. This proves that with strict enforcement, smart metering, and political will, the leak can be plugged.

The Cost of Inaction

Ignoring nontechnical losses renders all other investment futile. Building a solar farm for a community that does not pay for maintenance guarantees that the solar farm will be defunct within five years. As the data from Brazil and Nigeria illustrates, energy poverty is not just about wires and turbines. It is about the social contract. Until utilities can secure their revenue, the lights will stay off, no matter how many billions are spent on generation.

Investment Without Illumination

Bureaucratic Bottlenecks: Regulatory Hurdles Stifling Private Sector Participation

The global narrative on energy poverty often centers on a lack of capital. Yet, a closer inspection of the financial landscape between 2020 and 2025 reveals a more troubling paradox: funding exists, but it frequently fails to reach the ground. The primary obstruction is not a scarcity of dollars but an abundance of red tape. In Sub Saharan Africa alone, despite commitments of billions toward electrification, regulatory friction has frozen vast sums of potential investment. A striking statistic from the Africa Mini Grid Developers Association in 2024 highlights this dysfunction: only 14% of committed funding for mini grid projects had actually been disbursed to developers. The remaining 86% sat trapped in administrative limbo, held back by complex compliance requirements and slow verification processes.

The Licensing Labyrinth

For private developers, the journey from concept to connection is paved with paperwork. In many emerging markets, the regulatory process is not designed for the speed required to address the energy crisis. Data from 2022 indicates that for mini grid developers in Africa, regulatory compliance consumes an average of 58 weeks per project. Approximately 80% of this timeline is dedicated solely to securing licenses and environmental approvals. This delay is fatal for small companies with limited cash flow.

The situation in South Africa offers a stark example of how bureaucratic inertia stifles progress. As the nation grappled with severe power cuts known as load shedding, the private sector was eager to step in. However, reports from 2024 show that registering private solar installations could take between six and nine months. This lag forced businesses to burn diesel for nearly a year while waiting for permission to switch on clean energy systems that were already built and ready to operate.

The Transmission Trap

A major regulatory blind spot involves the disconnect between generation and transmission. Governments and investors have poured money into building power plants (generation) while neglecting the rules and funding needed to move that power (transmission). Between 2001 and 2023, roughly 97% of private investment in the Sub Saharan power sector went into generation assets, leaving a mere 0.2% for transmission expansion. This imbalance has created a “grid paradox” where countries have surplus electricity trapped at the plant, unable to reach consumers.

South Africa illustrates this failure vividly. Eskom, the state owned utility, estimated it required 14,000 kilometers of new transmission lines over the coming decade to integrate renewable energy sources. Yet, in 2023, the utility managed to construct only 326 kilometers. The regulatory framework for private participation in transmission infrastructure remained murky, effectively blocking the billions in private capital willing to close this gap.

Policy Lag in Nigeria

Nigeria presents another case study of regulatory sluggishness. The nation passed the Electricity Act in 2023, a landmark piece of legislation intended to liberalize the market and empower state governments. However, the operational frameworks required to spur real investment lagged significantly. It was not until late 2025 that the Nigerian Electricity Regulatory Commission finally issued clear commercial guidelines for interconnected mini grids. For two crucial years, uncertainty reigned. Investors held back capital because they could not predict how their assets would be treated if the main grid eventually reached their service areas. This hesitation stalled progress for the 85 million Nigerians who lack reliable access to the grid.

The Cost of Inaction

These bureaucratic delays are not merely administrative inconveniences; they are measurable economic taxes. Every week a project sits in a licensing queue is a week that a hospital burns expensive fuel or a factory reduces production. The World Bank notes that in Nigeria, the lack of reliable power forces businesses to rely on generators, driving up costs and stifling growth. When regulations treat small renewable projects with the same scrutiny as massive coal plants, the compliance cost becomes prohibitive. To unlock the billions sitting in bank accounts and deployed aimed at ending energy poverty, regulators must shift from site specific approvals to portfolio based licensing. Until then, the investment will remain theoretical, and the lights will stay off.

Ghost Projects: Case Studies of Infrastructure Commissioned But Never Energized

The global energy sector suffers from a disturbing paradox. While billions of dollars flow into power generation, the lights in millions of homes remain off. This phenomenon is best illustrated by “Ghost Projects.” These are massive infrastructure developments that are built, celebrated, and sometimes even commissioned, yet they fail to deliver a single watt of electricity to the consumer. Between 2020 and 2025, this trend accelerated across the developing world, revealing a fatal disconnect between generation capacity and grid reality.

The Nigerian Mirage: Kashimbila Hydropower Plant

Nigeria offers a stark example of the ghost project phenomenon. In May 2023, the federal government commissioned the Kashimbila Multipurpose Dam in Taraba State. Ideally, this facility would add 40 megawatts to the national grid, enough to power thousands of rural households. The turbines were ready. The water was flowing. Yet, for months after the ribbon cutting, the plant sat dormant.

The failure lay not in the dam itself but in the transmission infrastructure. The evacuation line required to transport power from Kashimbila to the Yandev substation was incomplete. By early 2024, the Minister of Power admitted that plans were still “underway” to evacuate the stranded 30 to 40 megawatts. The infrastructure effectively became an island of power in a sea of darkness. This case highlights a systemic flaw: the political preference for building glamorous power plants over the unglamorous but necessary transmission lines. Meanwhile, the Nigerian grid collapsed at least twelve times in 2024 alone, leaving the nation in blackouts while completed plants stood idle.

India and the Stranded Gigawatts

While Nigeria struggles with megawatts, India faces a ghost project crisis measured in gigawatts. A report from August 2025 revealed a staggering statistic: over 50 gigawatts of renewable energy capacity in India was classified as “stranded.” These were projects that had been awarded or built but could not come online.

The culprit was the same as in Nigeria: grid unavailability. Solar parks and wind farms were constructed at a breakneck pace to meet climate goals. However, the construction of high voltage transmission lines failed to keep up. Developers found themselves with acres of solar panels ready to harvest the sun, but with no wires to carry the energy to cities. This coordination failure meant that billions in capital investment sat unproductive. The energy was there, but for the consumer in New Delhi or Mumbai, it might as well have not existed.

South Africa: Corruption as a Barrier

In South Africa, the ghost project takes a different form. Here, the infrastructure is often delayed or rendered useless by corruption and design defects. The Kusile Power Station, a coal fired giant, became a symbol of this dysfunction between 2020 and 2023. Although units were technically commissioned, they frequently sat offline due to critical failures in flue gas desulfurization units and other control systems.

Investigations in 2022 and 2023 exposed how contracts were inflated and substandard work was approved. The result was a power station that consumed vast budgets while contributing intermittently to a grid desperate for stability. These “ghost units” existed on the asset register but provided little relief from the relentless load shedding that crippled the economy.

The Disconnect

These cases from 2020 to 2025 reveal a pattern. Governments and international lenders love to fund generation. A new dam or solar park offers a photo opportunity. Transmission lines, transformers, and grid upgrades are invisible to the public eye and offer little political capital. Consequently, they are neglected.

The result is a landscape of ghost projects: turbines spinning to nowhere and solar panels soaking up sun for no one. Until investment strategies shift from mere generation to holistic grid integration, the promise of light will remain a mirage for the billions living in energy poverty.

The Fuel Supply Chain: How Logistics and Shortages Cripple Functional Grids

The global narrative on energy poverty often centers on a lack of power plants. Yet, a more insidious failure mode has emerged across the developing world between 2020 and 2025. Nations with sufficient installed generation capacity are finding themselves in darkness, not because the turbines are missing, but because the fuel required to spin them cannot reach the site. This logistical paralysis, driven by debt, theft, and infrastructure decay, renders billions of dollars in grid investment useless. The power plants exist, but they sit idle, starved of coal, gas, or oil.

The Gas Paradox in West Africa

Nigeria offers the most stark example of this paradox. By early 2025, the country boasted an installed generation capacity exceeding 13,000 megawatts. However, the actual power delivered to the grid rarely surpassed 4,000 megawatts. The culprit was not a lack of demand or generation equipment, but a broken gas supply chain. Over 80 percent of Nigerian thermal plants rely on natural gas, yet pipeline vandalism and technical faults frequently severed this lifeline.

Data from 2024 revealed a systemic collapse. The Transmission Company of Nigeria recorded over twelve total grid failures that year alone. In many instances, gas pressure dropped to zero because upstream pipelines were breached by thieves or damaged by deferred maintenance. The Nigerian Independent System Operator noted in late 2024 that functional turbines were forced to shut down simply because the gas transport network could not deliver fuel. This logistical failure meant that for every three megawatts of capacity built and paid for, less than one megawatt reached consumers.

Rail Logistics and the Coal Crisis

In South Africa, the breakdown occurred on the rails. Eskom, the state owned utility, struggled to keep the lights on despite possessing massive coal fired power stations. The crisis here was exacerbated by Transnet, the national freight logistics company. Between 2020 and 2024, the volume of coal transported by rail to export terminals and domestic plants plummeted. In 2023, rail volumes hit a multi decade low.

The inability of the rail network to move coal efficiently forced power stations to rely on expensive and unreliable truck transport, which congested roads and failed to deliver the necessary volumes. Reports from 2024 indicated that Transnet’s collapse cost the South African economy billions of rand daily in lost output. The coal mines had the fuel, and the power stations needed it, but the connecting infrastructure had disintegrated due to theft of copper cables and locomotive shortages. This decoupling of mine and plant creates a scenario where energy abundance at the source translates to scarcity at the socket.

Circular Debt and Import Inability

In South Asia, the fuel supply chain is severed by financial rather than physical barriers. Pakistan faces a crippling “circular debt” crisis that has paralyzed its energy sector. By January 2024, this debt ballooned to over 2.6 trillion Pakistani rupees. The root cause is a payment failure loop: distribution companies fail to collect bills, the central power purchaser cannot pay the generation companies, and consequently, these generators cannot pay fuel suppliers.

This financial gridlock left viable power plants without fuel. In 2023 and 2024, despite having surplus installed capacity, long hours of load shedding were imposed because the government could not secure the foreign currency needed to import coal and liquefied natural gas. The fuel supply chain functioned physically but halted financially. Ships carrying LNG would bypass the country or wait at port, unable to unload until letters of credit were verified. The physical infrastructure was ready, but the financial logistics required to procure fuel had collapsed.

The High Cost of Volatility

Bangladesh faced a similar plight, exposed to the volatility of the international spot market. Heavily reliant on imported LNG, the country saw its energy security evaporate when prices spiked in 2022 and 2023. Unable to afford the spot rates, the government slashed imports, leading to widespread blackouts. In 2024, the dollar crisis further restricted the ability to pay for energy imports. This demonstrates that a fuel supply chain is only as robust as the capital available to secure the commodity.

The evidence from 2020 to 2025 is clear: functional grids are useless without functional logistics. Whether through physical vandalism in Nigeria, rail failure in South Africa, or financial paralysis in Pakistan, the inability to move fuel reliably is a primary driver of modern energy poverty. Investments in transmission lines and power plants will yield no light until the complex machinery of the fuel supply chain is fixed.

The Independent Alternative: Can Decentralized Solar Succeed Where Central Grids Failed?

In 2024, the national power network of Nigeria collapsed twelve times. On average, the system failed every thirty one days, plunging millions into darkness despite vast sums of capital poured into infrastructure over the last decade. This chronic instability illustrates a wider crisis across nations south of the Sahara, where centralized utilities struggle to serve growing populations. For years, the primary strategy for energy access was simple: extend the big cables. Yet, data from 2020 to 2025 suggests this centralized model is hitting a wall of insolvency and technical failure. In its place, a silent revolution of standalone solar and community networks is emerging, not merely as a temporary fix, but as a superior architecture for the future.

The numbers reveal a stark divergence between grid stagnation and the agility of distributed power. According to the 2024 market report by GOGLA, the global association for the independent solar industry, sales of solar energy kits reached 9.3 million units in 2024 alone. This represented a 4% growth from the previous year, showing resilience even as inflation battered local currencies. By early 2025, these systems were providing improved energy access to over 137 million people worldwide. While central utilities in nations like Zambia and Nigeria faced liquidity crises and infrastructure vandalism, the decentralized sector effectively bypassed these bottlenecks by delivering power directly to homes and businesses.

The Shift from Light to Livelihood

A critical trend observed between 2023 and 2025 is the evolution of solar from basic lighting to productive machinery. The “lights only” era is ending. It is being replaced by an era of solar water pumps, refrigeration units, and grain mills. GOGLA data highlights that sales of solar water pumps surged in 2024, driven by a desperate need for irrigation amidst changing climate patterns in East Africa. In this region, particularly in nations like Rwanda and Tanzania, adoption rates soared as farmers used digital finance models to pay for equipment over time. This mechanism, often called “pay as you go,” allows users to unlock solar hardware with small daily payments via mobile money, bypassing the need for traditional bank loans.

However, the market remains uneven. While East Africa saw robust growth, West Africa struggled. In 2024, sales in West African markets dropped by nearly 33%, largely due to currency devaluation and the removal of subsidies in Nigeria. This volatility exposes the fragility of the sector to macroeconomic shocks. Independent solar is not immune to the broader economy, but its modular nature allows for quicker recovery than billion dollar infrastructure projects that can stall for years.

The Investment Void

Despite the clear technical success of small local grids and standalone systems, a massive funding gap threatens to stall progress. The World Bank and GOGLA warned in late 2024 that the sector requires a sixfold increase in investment, totaling nearly 21 billion dollars, to achieve universal energy access goals. Current financial flows are a fraction of this necessary amount. Most global energy finance still gravitates toward massive generation projects which often fail to connect to the people who need them most. The World Bank estimates that for populations in remote areas, decentralized systems are the least expensive option for electrification, yet they receive a disproportionately small share of public funding.

The reality emerging in 2025 is that the central grid will never reach every village. The cost per connection in remote areas is simply too high, and the maintenance burden too great for debt ridden utilities. Distributed solar has proven it can succeed where the central model has failed, offering reliability in place of blackouts and local autonomy in place of dependence. The challenge now is not technology but finance. If global capital shifts from supporting zombie grids to scaling these agile networks, the light at the end of the tunnel will likely come from a solar panel on a tin roof, not a pylon on the horizon.

Human Cost Analysis: The Impact of Unreliable Power on Healthcare and Education

The modern world operates on the assumption of connectivity, yet for billions, the grid remains a distant rumor. While infrastructure discussions often focus on transmission lines and generation capacity, the true toll of energy poverty is paid in human lives and lost potential. Between 2020 and 2025, despite billions of dollars in allocated funds, the gap between investment and the functional reality in clinics and classrooms remained lethally wide.

The Power to Heal: A Matter of Life and Death

The most immediate human cost of energy poverty is found in the healthcare sector. A landmark 2023 report by the World Health Organization and partners revealed a staggering statistic: one billion people are served by healthcare facilities with unreliable electricity or no power at all. This is not merely an inconvenience; it is a structural failure that severs the link between medical knowledge and patient care.

In nations south of the Sahara, where the deficit is most acute, more than one in ten health facilities lack any electricity access whatsoever. The consequences are visceral. Without power, the cold supply chain for vaccines collapses. In a period defined by global pandemic response, the inability to refrigerate doses meant that vital immunizations spoiled before reaching the arms of patients. Estimates suggest that nearly half of vaccine supplies in some developing regions are wasted due to temperature excursions caused by power failures.

Maternal health bears a disproportionate burden. Childbirth does not pause for sunset. In clinics without reliable lighting, midwives are forced to deliver babies by the glow of kerosene lamps or mobile phone flashlights. This lack of illumination increases the risk of infection and complications during delivery. Furthermore, essential equipment like oxygen concentrators and incubators become useless paperweights without a steady current. The World Bank needs analysis from 2023 indicated that 4.9 billion dollars was urgently required just to bring these facilities to a minimal standard of electrification, a fraction of global energy spending that has yet to effectively materialize at the last mile.

The Power to Learn: The Silent Crisis

If healthcare suffers an acute crisis from energy poverty, education faces a chronic erosion of potential. The 2024 Energy Progress Report highlighted that 685 million people remained without electricity in 2022, with the vast majority in Africa. For students in these regions, the school day ends abruptly when the sun goes down.

This creates a phenomenon known as the homework gap. Children in electrified homes can study, read, and complete assignments after dark. Their peers in homes without power cannot. Over years of schooling, this deficit compounds, leading to lower exam scores and higher dropout rates. The digital divide further exacerbates this inequality. As education systems globally moved toward digital integration from 2020 to 2025, schools without power were left completely behind. Computers, tablets, and internet routers are meaningless without the electricity to run them.

Data from UNICEF indicates that access to power is a primary factor in teacher retention. Educators are reluctant to work in rural schools where they cannot charge a phone, use a laptop, or grade papers at night. The result is a cycle where the poorest communities receive the fewest resources, entrenching poverty for another generation.

The Investment Disconnect

Why do these deficits persist despite substantial financial flows? In 2022 alone, international public financial flows to developing countries for clean energy reached 15.4 billion dollars. However, this capital is often concentrated in a handful of nations, leaving the poorest regions starving for resources. Moreover, grid investment frequently prioritizes generation megaprojects over the decentralized solutions needed to reach rural clinics and schools. The wires may be strung, but if the current is not reliable, the human cost remains unpaid.

The failure to energize these vital sectors is not a technical problem but a failure of allocation and will. Until the metric of success shifts from megawatts generated to lives illuminated, the human cost of energy poverty will continue to rise.

Rewiring the Strategy: Policy Recommendations for Accountability and Sustainable Light

The era of writing blank checks to monopoly state utilities is ending. Data from 2020 to 2025 reveals that the most effective energy interventions have abandoned the “grid at any cost” dogma in favor of decentralized precision and rigorous financial accountability. For international donors and national governments, the path forward requires three fundamental shifts: enforcing results based financing, democratizing grid data, and legally empowering decentralized energy markets.

Recommendation 1: Flip the Financing Model

The most potent tool for accountability is Results Based Financing (RBF). Unlike traditional loans where funds vanish into procurement opacity before a single wire is strung, RBF releases capital only after verified connections are live. Rwanda stands as the premier case study for this pivot. In July 2025 the African Development Bank approved 173.84 million Euros for the Rwanda Energy Sector RBF II program. This initiative does not pay for promises; it pays for proven household connections and productive use appliances.

This model shifts risk from the public to the provider. Private developers and utilities must front the capital and deliver working electrons to get paid. The success is measurable: while centralized grid projects in the region often drag on for a decade with cost overruns, RBF schemes in Rwanda and Kenya have accelerated connection rates by incentivizing speed and efficiency. Policy frameworks must mandate that at least 50 percent of all new energy infrastructure loans be structured as RBF instruments by 2027 to stop the hemorrhage of public funds.

Recommendation 2: Digital Accountability and the “Glass Grid”

Corruption thrives in the dark, both literally and figuratively. A major barrier to accountability has been the state utility monopoly on information. Governments often do not know where the grid actually ends or which transformers are blown. The solution lies in independent digital monitoring.

Ghana offers a glimpse of this transparency through the GridWatch project. By deploying low cost sensors in households and businesses, regulators can now bypass utility reports and see real time outage data. This “Glass Grid” approach strips utilities of the ability to underreport downtime. In 2024 Nigeria saw its national grid collapse more than ten times, yet official explanations often blamed vague “system disturbances.” Mandatory installation of independent, automated grid monitoring systems must be a condition for any future international energy bailout. If a utility cannot prove it is providing power, it should not receive funding.

Recommendation 3: Legal Protection for Decentralized Utility

The final rewire involves ending the legal hostility toward mini grids. For years, state utilities in countries like South Africa and Nigeria viewed decentralized solar as a threat to their revenue base. However, the 2023 and 2024 data is clear: state monopolies are collapsing under debt and inefficiency. Sierra Leone provides a roadmap for correction with its Rural Renewable Energy Project (RREP). By explicitly carving out legal zones for private mini grids, the country attracted developers to build over 90 systems that operate independently of the troubled national grid.

Togo also demonstrated this with its CIZO program, which legally integrated Pay As You Go solar companies into the national electrification strategy. By 2024 the program had subsidized nearly 80,000 households, proving that private companies can deliver public goods when protected by clear regulation. Governments must enact legislation that grants mini grids permanent operating licenses and tariff autonomy, shielding them from the predatory reach of failing state entities.

Conclusion

The definition of energy poverty is not just a lack of wires; it is a lack of accountability. We have the technology to light up the world. The missing link has been the political will to break the monopoly models of the 20th century. By enforcing payment for results, demanding radical data transparency, and unleashing the decentralized sector, we can finally turn investment into illumination.

Infographic You may Use:

The Global Energy paradox

*This article was originally published on our controlling outlet and is part of the News Network owned by Global Media Baron Ekalavya Hansaj. It is shared here as part of our content syndication agreement.” The full list of all our brands can be checked here.

Request Partnership Information

Ekalavya Hansaj

Part of the global news network of investigative outlets owned by global media baron Ekalavya Hansaj.

Ekalavya Hansaj is a force in worldwide media relations, not only a name. Ekalavya has transformed silence into spotlight for the world's most elusive brands and contentious people with a voice that commands headlines and a mind designed for strategy. While some view PR as press releases and soundbites, he views it as narrative war—narrative war. He triumphs. Born with only an unparalleled natural ability for influence, Ekalavya didn't rise the ranks; he constructed his own ladder, burned it, and changed the media interaction rules in the smoke. From underground businesses to billion-dollar boardrooms, he has coordinated media storms that have changed policies, rocked continents, and shaped public opinion. For better or worse, he knows what drives people, what keeps headlines relevant, and what causes reputations to explode. Ekalavya Hansaj doesn't tell tales. He designs emotional pull. He ignores fads. He designs stories that set the trend. Elites whisper and rivals dread Ekalavya Hansaj when your story has to be told with impact, reach, and ruthless accuracy. In the media war, he is the weapon.