Why it matters:

- Investment frenzy in solar grids promised financial returns and social impact

- By 2025, sector faced a brutal correction with a collapse in confidence and capital flows

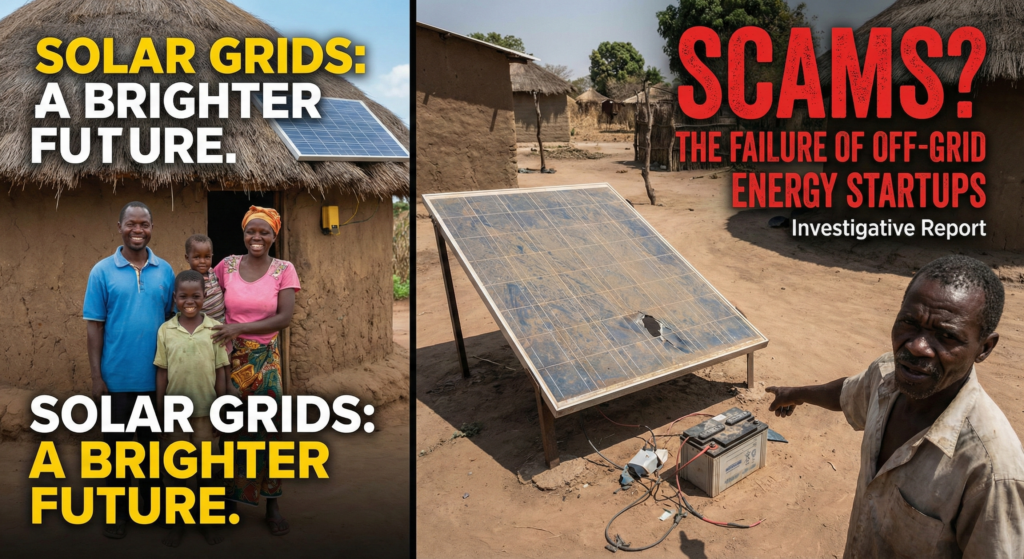

The narrative about solar grids sold to venture capitalists in London and Silicon Valley was irresistible. It promised a dual victory: massive financial returns paired with immense social impact. The pitch described a leapfrog technology, much like mobile phones skipping landlines, where standalone solar units would bypass the decrepit central power networks of the Global South. Between 2020 and 2022, this story drove a frenzy of investment, pouring nearly 800 million dollars annually into the sector at its peak. Investors saw not just energy companies, but fintech unicorns in the making. They believed they were funding the next revolution in digital credit, using solar panels as the collateral for loans to unbanked populations across Africa and Asia.

By early 2025, however, the golden sheen had begun to fade, revealing a harsher reality. The sector, once overflowing with optimism, faced a brutal correction. Data from industry associations reveals that global capital flows into these decentralized energy markets plummeted to just over 300 million dollars in 2024, a drop of nearly sixty percent from the 2022 highs. The pullback was not merely a pause but a structural collapse in confidence for all but the largest players. While giants like Sun King and d.light continued to secure massive debt facilities in 2025—such as the 300 million dollar receivables financing for d.light—smaller ventures found themselves starved of cash. The market had bifurcated: a few “too big to fail” incumbents absorbed the remaining capital, while a long tail of smaller innovators faced insolvency.

The core problem lies in the business model itself. Known widely as “metered payment schemes” or digital credit energy, the approach allows customers to pay for solar kits in small daily installments. In theory, this unlocks access for poor households. In practice, it mimics the mechanics of subprime lending. As inflation surged across Nigeria, Kenya, and Pakistan throughout 2023 and 2024, the ability of rural customers to service these debts evaporated. Default rates spiked. The very model meant to empower the poor began to look predatory, trapping vulnerable families in debt cycles for essential light. Reports from 2024 indicated that roughly 36 percent of customers in some markets lost their access to energy after defaulting, leaving them in the dark with nothing to show for their partial payments.

This financial strain exposed the fragility of the “growth at all costs” mentality. Investors had pushed these young firms to prioritize sales volume over portfolio quality. The result was a massive deployment of hardware to customers who could not afford it over the lasting duration of the loan. When the global interest rate environment shifted, the cheap money sustaining these operations vanished. The cost of borrowing for the firms themselves skyrocketed, compressing margins that were already razor thin. The dream of a profitable, market driven solution to energy poverty clashed violently with the economic volatility of the target nations.

Now, as we examine the wreckage and the survivors in 2026, a critical question emerges. Was the initial rush a genuine attempt to solve a global crisis, or was it a speculative bubble built on the exploitation of the world’s poorest citizens? The “Green Gold Rush” has ended, leaving behind a landscape of broken hardware, distressed debt, and a consolidated monopoly of corporate giants. The following investigation peels back the layers of this complex failure, analyzing how a technology hailed as a savior became a symbol of broken promises.

The Promise of Pay As You Go (PAYG) Solar Models

The narrative sold to venture capitalists between 2020 and 2022 was seductive in its simplicity. Investors were told that Pay As You Go (PAYG) solar would do for electricity what mobile phones did for communication in Africa: leapfrog the heavy infrastructure of the past. The model relied on a blend of hardware and fintech. A customer in Sub Saharan Africa would pay a small deposit for a solar home system, then unlock daily energy usage via mobile money payments of roughly $0.50. It was pitched as a win for both profit and planet. By 2022, this optimism peaked. Global investment in the off grid solar sector swelled to $746 million, a 63 percent jump from the previous year, with giants like Sun King and MKOPA attracting massive equity rounds.

However, data from 2023 through 2025 reveals a harsh divergence between this financial promise and operational reality. The core mechanism of the PAYG model—financing hardware over time—became its undoing when macroeconomic headwinds hit. The primary culprit was currency volatility. Most off grid startups raised capital in hard currency (USD or Euros) to purchase inventory from China, yet they collected revenue in local soft currencies. When the Nigerian Naira lost 50 percent of its value against the dollar in 2023, the mathematics of repayment collapsed.

The Forex Trap

The impact of this currency mismatch was immediate and devastating. In 2024, while global sales of solar energy kits inched up by 4 percent, sales in West Africa plummeted by 33 percent. The Nigerian market, once the crown jewel of expansion strategies, was hammered by the devaluation and high inflation. Companies could not pass the full cost of currency depreciation onto low income customers without triggering mass defaults.

This financial pressure forced a wave of consolidation and exits. In September 2022, Bboxx acquired PEG Africa, a major player in West Africa with 250,000 customers. While framed publicly as a growth move, industry insiders viewed such mergers as necessary survival rafts for companies unable to raise fresh capital in a high interest rate environment. Smaller operators without the balance sheet to weather currency shocks simply vanished or were absorbed.

From Energy to Fintech

Perhaps the most telling trend of 2024 and 2025 is the pivot away from pure energy access. To survive, the “solar” companies are morphing into digital asset financiers. MKOPA, one of the sector’s most visible success stories, reported its first ever profit in 2024, swinging to a $9.2 million gain from a $24.7 million loss the prior year. Yet, a closer look at their 2024 performance shows this turnaround was driven largely by smartphone financing rather than solar panels alone.

The device locked smartphone became a more lucrative asset than the solar home system. It offered better repayment data, higher customer demand, and shorter loan cycles. By 2025, the sector effectively split in two. On one side are the “commercial” winners like MKOPA and d.light, shifting toward urban and peri urban customers who want phones and appliances. On the other remains the original target demographic: the 685 million people still without electricity, mostly rural and poor, for whom a commercially viable solar solution remains out of reach without subsidies.

The stagnation of PAYG sales growth, which saw only a 1 percent increase in 2024, suggests the organic market for unsubsidized solar has hit a ceiling. The startup model worked to reach the first tier of solvent customers, but it has struggled to penetrate deeper into the poverty curve where the risk of default outweighs the potential return. The promise of universal access through venture backed startups has collided with the hard wall of customer insolvency.

Venture Capital and the Impact Investing Bubble

The promise was intoxicating. It combined the ruthless efficiency of Silicon Valley with the moral sanctity of humanitarian aid. Between 2010 and 2020, venture capitalists poured over two billion dollars into companies promising to electrify Africa through decentralized solar power. They sold a vision where rural villagers would leapfrog traditional utility poles just as they had skipped landline telephones. But by 2023, the narrative shifted from technological revolution to financial distress. The sector had not built a sustainable utility model; it had constructed a subprime lending bubble masked as environmental altruism.

Investors treated these hardware heavy utility businesses like software unicorns. They demanded growth rates that defied the physics of logistics and the economics of poverty. The result was a distinctive boom and bust cycle that unraveled markedly between 2020 and 2025. During this period, the fundamental flaw in the model became undeniable: most customers could not afford the product without financing that the companies could not afford to offer.

The Valuation Trap and Distorted Metrics

The core error lay in how these firms were valued. Investors used multiples suitable for software companies (SaaS) rather than hardware distributors. They focused on “connections created” rather than “unit profitability.” This pressure forced operators to expand aggressively into territories with lower customer creditworthiness. By 2022, the Global Off Grid Lighting Association (GOGLA) reported that while sales volumes were high, the credit health of the portfolios was deteriorating. Companies were prioritizing new user acquisition to justify the next funding round while ignoring the mounting bad debt from existing users who had stopped paying.

The Currency Crisis of 2022 to 2024

The bubble burst when macroeconomic reality struck. These ventures raised capital in United States Dollars but collected revenue in local currencies like the Nigerian Naira, Kenyan Shilling, and Ghanaian Cedi. When global inflation surged in 2022, these local currencies plummeted. The Nigerian Naira lost nearly 70% of its value against the dollar between 2023 and 2024. For a solar provider in Lagos, this meant their debt obligations to foreign investors effectively tripled overnight, while their customers, battling the same inflation, defaulted on their monthly solar payments.

This mismatch annihilated balance sheets. The acquisition of PEG Africa by Bboxx in 2022 was widely celebrated as consolidation, but investigative reports suggest it was a rescue sale necessitated by unsustainable debt structures. PEG had expanded rapidly across West Africa, yet the currency devaluation in Ghana rendered their dollarized liabilities toxic.

Securitization as a Survival Tactic

As equity investors fled in 2023, recognizing that returns would never match the 10x promise of tech, the industry pivoted to complex debt instruments. Companies began packaging their customer loans into securities to sell to impact investors. Sun King and d.light raised hundreds of millions through these securitized facilities between 2022 and 2025. While this kept cash flowing, it merely kicked the can down the road. These structures rely on the assumption that impoverished rural customers will maintain repayment rates above 90% over years. Data from 2024 suggests that in markets facing food insecurity, repayment rates for solar kits often drop below 70%, turning these securitized assets into ticking time bombs.

The venture capital model demanded speed and scale. Energy access requires patience and infrastructure. By forcing the former onto the latter, impact investors created a fragile ecosystem. The resulting insolvencies and fire sales witnessed through 2025 were not just business failures; they were the inevitable correction of a market that valued the pitch deck over the profit and loss statement.

Hardware Durability: Cheap Components in Harsh Environments

The marketing narrative for autonomous solar energy often relies on a seductive image: sleek, futuristic panels bringing light to the darkest corners of the Global South, allowing developing nations to leapfrog traditional infrastructure entirely. Yet, investigations on the ground reveal a grittier reality. Instead of a permanent utility, many customers are purchasing what amounts to disposable electronics. The collision between cost constrained engineering and the brutal physical realities of rural Africa and Asia has created a hardware crisis that threatens to bury the sector in broken plastic and toxic chemicals.

The Thermal Breaking Point

Engineers design most solar components in climate controlled labs in Shenzhen or Silicon Valley, testing them at a standard 25 degrees Celsius. However, the target markets for these devices—places like rural Northern Nigeria, Rajasthan in India, or the arid plains of Kenya—regularly see ambient temperatures soar above 40 degrees. Data from 2024 indicates that for every 8 degree Celsius rise above the optimal range, battery life efficiency is cut by nearly 50 percent. This thermal stress is catastrophic for cheap lithium ion cells and leads to rapid degradation.

The Battery Management Systems (BMS) used in budget solar kits are frequently the first point of failure. To keep upfront costs low for the “pay as you go” (PAYG) model, manufacturers often utilize generic circuitry that lacks adequate thermal protection or voltage balancing. Once the BMS fails, the battery either bricks itself to prevent a fire or swells up and dies. A 2023 report by the University of New South Wales highlighted that while premium lithium units promise a decade of service, many consumer grade off grid products function for less than four years. Some fail within months, leaving the user with a useless object they are contractually obligated to keep paying off.

A Tsunami of Dormant Waste

The scale of this failure is staggering. According to a 2024 estimate cited by ESI Africa, the sector has distributed approximately 375 million energy kits since the early 2000s. Of those, experts estimate that more than 250 million have fallen into disrepair. This is not merely a historical problem but an accelerating one. A study published in 2023 involving SolarAid data suggests that nearly 75 percent of distributed solar kits in studied African regions have ceased functioning.

Unlike mobile phones, which have established recycling networks, broken solar lanterns and home systems often enter a state of “hibernation.” Research from 2023 reveals that 90 percent of customers retain their broken devices, storing them in corners or under beds in the desperate hope that a repair technician might one day arrive. They rarely do. The logistical cost of retrieving a ten dollar broken lantern from a remote village exceeds the value of the device itself, leaving the burden of disposal entirely on the customer.

The Toxic Aftermath

When these devices finally exit the home, they do not go to formal recycling centers. In 2020, the sector produced an estimated 10,000 tonnes of electronic waste, a figure that has grown annually as the 2018–2020 sales cohort reaches end of life. In the absence of formal infrastructure, informal “recyclers” often burn the plastic casings to harvest small amounts of copper and aluminum, releasing toxic fumes. The lithium and lead from the batteries leach into local soil and water tables. The “clean energy” revolution, in its current hardware iteration, risks leaving a legacy of chemical pollution in the very communities it promised to save.

The financial implication is equally severe. Impact data from 60 Decibels in 2022 and 2023 showed that 34 percent of energy customers reported technical challenges with their products. For a family living on irregular income, buying a solar kit is a massive capital investment. When that hardware fails prematurely, it does not just mean a return to darkness; it represents a destruction of wealth for the world’s poorest citizens.

The Hidden Debt: Predatory Lending Disguised as Utility

The narrative was perfect. Silicon Valley venture capitalists and European development funds poured billions into a sector promising to leapfrog the fossil fuel era. They pitched a story of empowerment where families in Sub Saharan Africa would bypass the central grid just as they bypassed landlines for mobile phones. But beneath the glossy marketing of clean energy access lies a different reality. By 2024, the off grid solar sector had quietly mutated. It was no longer strictly about energy. It was about unregulated subprime lending.

The primary mechanism driving this industry is the pay as you go model. Customers put down a small deposit for a solar home system and pay the rest in daily micropayments via mobile money. If they miss a payment, the device shuts down remotely. Investors love this collateral. It turns a physical asset into a credit enforcement tool. However, data surfacing between 2020 and 2025 reveals that the effective interest rates on these utility contracts often rival those of loan sharks.

A pivotal example is M KOPA, a dominant player in the East African market. In late 2024, the company reported its first profit of 1.2 billion Kenyan Shillings, or roughly 9.2 million dollars, with revenues surging 66 percent to 416 million dollars. This financial success story, however, hid a stark cost for the consumer. Independent academic reviews cited in 2025 financial reports calculated that the effective annual interest rates on some of these financing plans reached as high as 254 percent. While banks face strict caps on interest rates, these firms operate in a regulatory gray zone. They claim to sell products, not loans, allowing them to bypass consumer protection laws that govern traditional lenders.

The industry defense is that high operational costs justify these premiums. Yet the business model has shifted away from simply providing light. The 2024 Global Off Grid Solar Market Report by GOGLA and the World Bank noted that while 685 million people remained without electricity, the commercial focus had drifted. Companies found that selling solar panels to the rural poor was slow and risky. The new gold mine was digital finance. M KOPA and its peers aggressively pivoted toward financing smartphones and cash loans using the same lockout technology. By 2025, the solar panel had become merely a customer acquisition tool, a gateway drug to enter a cycle of high interest consumption debt.

This pivot exposes the “utility” facade. A true utility provider has a mandate to deliver essential services at affordable rates. These startups function more like tech enabled rent to own retailers. The debt burden is invisible to sovereign balance sheets but crushing for households. In Kenya and Nigeria, families often pay significantly more for these assets than their cash value. When a customer defaults after paying 80 percent of the cost, the device locks. The company retains the equity. The user is left in the dark.

The capitalization of these firms reflects this predatory shift. Between 2020 and 2023, while pure play energy access startups struggled to raise equity, companies framing themselves as “fintech for the underserved” attracted massive rounds. Investors sought the high returns of unsecured consumer lending rather than the slow, regulated returns of infrastructure projects. The result is a sector that extracts capital from the world’s poorest populations under the guise of green development.

By 2025, the hidden debt crisis had become undeniable. The disconnect between the mission of energy access and the reality of asset financing created a bubble of vulnerability. Families were not just buying light; they were buying entry into a financial system rigged against them, where the repo man was a line of code and the interest rate was buried in the daily fee.

Solar Grids Crisis

Remote Kill Switches: The Ethics of Digital Repossession

The promise was simple and seductive. For a deposit of thirty dollars, a family in rural Kenya or Nigeria could bypass the failing national grid and install a solar home system. They would pay for it over time, a few cents a day, using mobile money. But hidden inside the plastic casing of these yellow and orange boxes sits a dormant threat: a subscriber identity module, or SIM, linked to a central server. This is the kill switch. When payments stop, the light goes out.

By 2024, the “pay as you go” (PAYG) sector had connected millions across Africa and Asia. Yet, as inflation surged and currencies like the naira and shilling tumbled, the utopian narrative of energy access collided with the brutal reality of digital repossession. Investigations reveal that for many customers, the gridless dream has become a debt trap, enforced not by repo men, but by code.

The Mechanics of Darkness

The technology is efficient and ruthless. Providers like M Kopa, Bboxx, and d.light utilize Internet of Things (IoT) connectivity to monitor usage. If a customer misses a daily micropayment, the device is disabled remotely. The lights do not dim; they simply cease to function. The battery remains full, the panel soaks up the sun, but the software locks the user out of their own hardware.

Data from GOGLA, the association for the independent solar industry, shows that 2024 sales reached 9.3 million units, a recovery from the pandemic lows. However, behind these volume numbers lies a rising tide of default. A 2025 study by impact researcher 60 Decibels exposed a troubling transparency gap: nearly half of defaulted customers were unaware that their devices could be remotely disabled. Thirty one percent did not fully understand the payment terms when they signed up. For these users, the sudden darkness was not just an inconvenience but a shock, leaving them confused and powerless.

The Deye Lockout Scandal

The danger of this power asymmetry moved beyond small lanterns in late 2024. A controversy involving Deye, a major inverter manufacturer, illustrated the scale of the risk. Reports emerged that Deye had remotely disabled inverters across the United States and Europe due to contract disputes with local distributors. Homeowners who had paid thousands of dollars for their systems found them “bricked” overnight. The incident served as a chilling proof of concept: in the modern energy landscape, ownership is an illusion. The manufacturer retains the ultimate power to disconnect.

Predatory Inclusion?

Critics argue this model represents “predatory inclusion.” Investors demand growth and low default rates. In response, companies aggressively market to impoverished households, using the kill switch as a substitute for credit checks. The device itself becomes the collateral. When economic headwinds hit, as they did violently in 2023 and 2024, the poorest customers face a binary choice: buy food or buy light.

The numbers paint a stark picture. In 2024, sales of solar lanterns in West Africa dropped by 33 percent as disposable incomes evaporated. Families who could no longer service their PAYG debts were left with useless plastic bricks. The waste is not just financial but environmental; a locked device is effectively e waste sitting in a living room.

Startups argue that without the remote lockout capability, they could not lend to the unbanked at all. They frame the technology as a necessary enabler of credit. Yet, the 2025 default data suggests that for many, this credit bridge has collapsed. The industry now faces a reckoning. Is it truly delivering energy independence, or is it building a new, decentralized infrastructure of control, where the poorest pay the highest premium for the basic right to see in the dark?

The Last Mile Logistics Nightmare

The sleek investor decks presented in London and San Francisco often feature maps with glowing dots, representing thousands of rural homes illuminated by solar power. These digital visualizations suggest a frictionless expansion of energy access. However, the operational reality on the ground in 2024 reveals a brutal truth: the logistics of reaching the final customer are destroying profit margins and driving the sector toward a silent crisis. While software can be scaled infinitely at near zero marginal cost, moving physical hardware through rural hinterlands cannot.

Data from the 2024 GOGLA Market Trends Report exposes the severity of this disconnect. While the industry sold 9.3 million solar energy kits globally in 2024, distinct regional fractures have emerged. In West Africa, sales plummeted by 33 percent. The primary culprit was not a lack of demand but an inability to serve customers affordably amidst macroeconomic chaos. When inflation spiked fuel prices across Nigeria and Ghana in 2022 and 2023, the cost of deployment doubled overnight. A standard service call, once calculated at five dollars per visit, ballooned to over ten dollars, obliterating the lifetime value of smaller customer accounts.

The “last mile” is often a misnomer; for many field agents, it is the last fifty miles of unpaved, mud slicked roads. Companies like Bboxx and Sun King have invested millions in logistics fleets, yet they face a relentless rate of vehicle attrition. In the rainy seasons of Rwanda or Kenya, motorcycles break down, delivery trucks get stuck, and inventory sits idle in regional warehouses. Each day a system sits in transit is a day of lost revenue. More critically, when a deployed panel fails or a battery degrades, the logistics of reverse supply chains become a financial black hole. Retrieving a faulty unit from a remote village often costs more than the hardware itself. Consequently, many customers are left with nonfunctional units, leading to a sharp rise in default rates. If the light does not turn on, the customer does not pay.

This logistical pressure cooker has forced a wave of defensive consolidation. The acquisition of PEG Africa by Bboxx in September 2022 was widely heralded as a growth story, but industry insiders view it through a different lens: survival through density. By merging operations, these firms attempt to amortize their colossally high distribution costs across a larger customer base. Standalone operators lacking this scale are quietly bleeding cash. The World Bank estimates that reaching universal access targets by 2030 requires 21 billion dollars in funding, yet private equity is retreating, spooked by the high operating expenses (OPEX) that define the sector.

Furthermore, the dependency on imported hardware adds another layer of logistical risk. The 2022 global supply chain crunch saw container prices skyrocket, delaying shipments of batteries and panels from Shenzhen to Mombasa by months. For a “pay as you go” business model dependent on constant inventory turnover, these delays were catastrophic. Cash flow dried up as stock sat in containers rather than on tin roofs generating daily micropayments. The nightmare is not just about moving boxes; it is about the synchronization of physical delivery with digital finance in environments where neither infrastructure is reliable.

The startup narrative of “leapfrogging” the grid ignored the fact that the grid provided more than just electrons; it provided a maintenance pathway. Decentralized energy demands decentralized logistics, which is inherently inefficient. Until drone delivery becomes a reality rather than a PR stunt, or until rural road infrastructure improves dramatically, the last mile will remain the graveyard of unit economics. The 33 percent drop in West African sales is a warning flare: without a radical rethinking of distribution, the solar revolution stops where the pavement ends.

Mobile Money Limitations and High Collection Costs

The promise of standalone solar energy was built upon a digital foundation. Investors were told that mobile money would eliminate the need for physical debt collectors. They believed that a simple digital signal could lock a solar unit if payment stopped, forcing the user to pay up. This digital barrier was supposed to guarantee revenue. However, data from 2020 to 2025 reveals a harsh reality where the cost of collecting small payments destroys profit margins.

The entire business model relies on the assumption that customers will pay voluntarily to keep their lights on. When they stop, the system crumbles. The industry calls this “repayment risk,” but investigative documents show it is actually a crisis of collection logistics. In 2024, a tax tribunal in Kenya exposed the internal mathematics of this failure. MKOPA, a major player in the sector, revealed that recovering bad debt is financially impossible.

Court documents from the 2024 tribunal showed that MKOPA faced 1.4 billion Kenyan Shillings in bad debt. The company argued it should not pay taxes on this lost revenue because chasing the defaulters would cost more than the debt itself. The firm estimated that tracking down a single defaulter cost approximately 20,000 shillings. If they pursued legal action, the cost would balloon to nearly 110,000 shillings per customer. Since the average outstanding debt was often a fraction of that amount, the company had no choice but to let the money go. The “asset financing” model fails because the asset has almost no recoverable value once it is in a rural home.

This reality contradicts the pitch made to venture capitalists. The startup claim was that technology had solved the collection problem. In truth, the technology only works when the customer has money. When a user in rural Africa or Asia faces a crop failure or a medical emergency, a locked solar unit does not generate cash. It simply becomes a useless plastic box. The company cannot afford to send an agent to retrieve it, so the device sits idle while the startup writes off the loss.

Currency volatility further exposes the fragility of this collection model. Between 2023 and 2024, the Nigerian Naira lost over forty percent of its value against the US Dollar. Solar companies buy panels and batteries in dollars but collect payments in Naira. When the local currency collapses, the startup effectively collects half the value it needs to repay its own investors. To survive, companies must raise prices for new customers, which shrinks their total market and increases the temptation for users to default.

The 2024 Global Off Grid Solar Market Report highlights that only twenty two percent of households without electricity can afford even the most basic monthly plan. This leaves the vast majority of the potential market unable to sustain payments. When these customers inevitably miss a mobile money transfer, the company faces a binary choice: unlock the device for free or abandon the customer. Most choose to abandon the customer.

Mobile money networks themselves are not the seamless solution often advertised. Transaction fees for small payments can eat up to ten percent of the user expenditure. For a family living on two dollars a day, these fees are a significant barrier. Network downtime in remote areas also prevents willing customers from paying, leading to automatic blackouts. The frustration causes users to hack the devices or revert to kerosene, leaving the solar company with phantom revenue that never arrives.

The failure here is not just a business loss but a waste of resources. Thousands of solar home systems now sit collecting dust in rural homes, locked by a remote server. The startup cannot afford to collect them. The user cannot afford to unlock them. This creates a landscape of electronic waste rather than energy access. The dream of a frictionless, digital energy grid has collided with the friction of physical poverty and logistical expense.

The Customer Acquisition Trap: Prioritizing Growth Over Creditworthiness

The collapse of confidence in the off grid solar sector between 2020 and 2025 was not merely a result of technical failure or logistical hurdles. It was the direct consequence of a financial trap set years prior. Venture capital investors, accustomed to the explosive user growth of Silicon Valley software companies, demanded similar trajectories from African energy hardware providers. To meet these unrealistic expectations, executives at top firms prioritized customer acquisition speed above all else, including the fundamental ability of those customers to repay their loans.

This dynamic created a toxic asset bubble disguised as social impact. By 2022, the industry faced a reckoning. Reports from GOGLA, the global association for the off grid solar energy industry, revealed a disturbing trend: collection rates for pay as you go (PAYG) companies had stagnated or declined. In 2023, while the sector celebrated reaching millions of households, the underlying financial health was deteriorating. Data indicated that collection rates hovered around 62 percent for many operators, meaning nearly four out of every ten dollars owed were not being collected.

The mechanism of this failure was simple but devastating. Sales agents, often paid on commission per unit installed rather than per loan repaid, were incentivized to sign up anyone with a roof. Credit checks were minimal or nonexistent. In rural markets across Kenya, Nigeria, and Uganda, agents sold complex financial products to subsistence farmers who lacked stable cash flows. When inflation spiked global food and fuel prices in 2022 and 2023, these customers were the first to default. They did not stop paying because they wanted to steal the solar kits; they stopped because they had to choose between light and food.

The fallout was severe. Investment in the sector plummeted as the bad debt became impossible to ignore. According to GOGLA investment data, total funding for the off grid solar sector dropped by 43 percent in 2023, falling to roughly 425 million dollars. Startup capital, the lifeblood of new innovation, crashed by 70 percent. Investors who had once poured millions into the promise of “lighting up Africa” suddenly closed their checkbooks, spooked by the realization that their growth metrics were built on a foundation of non performing loans.

Specific companies bore the brunt of this shift. PEG Africa, once a darling of the West African market, faced significant pressure due to debt struggles before being acquired by Bboxx in 2022. While the acquisition was framed as consolidation, industry insiders viewed it as a rescue operation for a company overleveraged by the push for rapid expansion. Similarly, Zola Electric (formerly Off Grid Electric) had to radically pivot its business model. moving away from simple residential systems toward more complex distributed energy technology, effectively acknowledging that the original model of mass market residential leasing was fraught with unmanageable risk.

The customer acquisition trap also forced a moral retreat. To survive the liquidity crisis of 2024, many surviving companies quietly shifted their focus away from the poorest customers the very people they were founded to serve. They pivoted toward higher income peri urban clients or business to business sales where default risk was lower. The “growth at all costs” era effectively ended the dream of universal access for the ultra poor, proving that without subsidies, a venture backed model cannot reconcile the demand for high returns with the reality of low income credit risk.

Case Study: The Collapse of High-Profile Off-Grid Unicorns

The narrative of decentralized energy in Africa was once dominated by a singular, intoxicating promise: the Silicon Valley model could solve energy poverty. Venture capitalists poured billions into companies that pitched themselves not as utility providers, but as tech platforms. They promised exponential growth, massive user bases, and data monetization. By 2025, however, this valuation bubble had burst, revealing a landscape littered with insolvent startups, distress sales, and a fundamental failure of the debt financed model.

The Unicorn Mirage

Investors sought unicorns, entities valued at over one billion dollars, in a sector that required moving heavy hardware to remote villages. This mismatch created a “growth at all costs” culture. Companies like Mobisol, which fell into insolvency in 2019, set a grim precedent. Yet, between 2020 and 2024, the industry repeated these mistakes, fuelled by cheap capital. When global interest rates spiked in 2023, the foundation crumbled. The cost of servicing debt for customer loans became unsustainable, exposing the fragility of the “scale first, profit later” approach.

Pawame and the Administration Trap

A stark example of this collapse is the Kenyan solar startup Pawame. Once heralded as a market leader, Pawame entered administration in 2022. The company had raised significant venture funding but struggled with the intense capital requirements of the PAYG model. Providing solar kits on credit requires massive upfront cash. When customers default, the company holds the bag. Pawame faced a liquidity crunch as it could not raise fresh capital fast enough to cover its operational burn and hardware costs. Its placement into administration sent shockwaves through the sector, proving that even well backed players were not immune to basic unit economics.

The PEG Africa Fire Sale

In late 2022, another major player, PEG Africa, was acquired by Bboxx. While press releases celebrated the deal as a consolidation of strength, industry insiders viewed it differently. PEG Africa had significant operations across West Africa but carried a heavy debt load. The acquisition came during a funding winter when equity for standalone power companies had dried up. Instead of a triumphant exit for early investors, the sale was a necessary maneuver to prevent another collapse. It highlighted a new reality: the fragmented market could not support dozens of independent operators carrying millions in consumer debt.

The 2024 Debt Crisis

By 2024, the rot had spread to the balance sheets of the largest operators. A report by 60 Decibels released in 2025 revealed that default rates on solar loans had surged to 30 percent in 2023, up from 18 percent just two years prior. Inflation and currency devaluation in markets like Nigeria and Kenya decimated the purchasing power of rural customers. They simply stopped paying. For companies that had securitized these loans to borrow more money, this was catastrophic. The “asset” they held was not the solar panel, but the loan, and that asset was now worthless.

The Hardware Graveyard

The final blow to the unicorn dream was the physical reality of the technology. By 2024, an estimated 250 million solar kits sat in disrepair across the Global South. The rush to flood the market led to poor quality control and nonexistent aftersales service. Customers with broken units refused to pay their remaining installments. This “hardware graveyard” destroyed brand trust and further spiked default rates. The startups had optimized for sales numbers to please VCs but failed to build the logistics network needed to maintain the equipment.

Ultimately, the collapse of these prominent players marked the end of the venture capital era in rural electrification. The sector is now pivoting towards a utility focused model, prioritizing slow, sustainable growth and collection efficiency over the empty calorie metrics of user acquisition.

Toxic Assets: Managing Default Rates and Bad Debt

The narrative of decentralized energy often features a smiling customer switching on a light for the first time. It rarely features the collection agent standing outside that same home two years later. By 2024, the solar sector for the developing world faced a reckoning that looked less like a utility revolution and more like a subprime lending crisis. The core asset of these companies is not the solar panel but the loan attached to it. When that loan fails, the hardware on the roof transforms from a beacon of progress into a toxic asset.

The Repayment Reality Check

Between 2020 and 2025, the industry saw repayment metrics deteriorate sharply. Data from GOGLA, the global association for the industry, revealed a troubling trend. While companies projected default rates below 5 percent in their pitch decks, reality proved far harsher. By 2023, the write off ratio plus receivables at risk surged significantly. Reports indicated that half of all companies in the sector faced a portfolio risk ratio between 30 percent and 50 percent. This means nearly half of their deployed capital was either in default or perilously close to it.

Sector Snapshot (2021 to 2023): The average collection rate across the industry stagnated at 62 percent. Companies in the bottom quartile saw collection rates drop below 50 percent, meaning they collected less than half the revenue owed to them each month.

The lockout technology, which remotely disables the solar unit if payments are missed, was marketed as the ultimate collateral security. In practice, it failed to guarantee revenue. A dark house pays no bills. Once a customer stops paying, the provider faces a dilemma. Retrieving a system from a remote village in rural Kenya or Nigeria often costs more than the hardware is worth. The unit stays on the roof, disabled and degrading, while the debt remains on the corporate balance sheet as a “receivable” that will never be received.

The Currency Trap

The crisis was compounded by macroeconomic shocks that no algorithm could predict. Most solar startups raised debt in US dollars but collected revenue in local currency. When the Nigerian Naira or the Kenyan Shilling crashed, the math broke. In 2024, sales in West Africa plummeted by 33 percent, driven largely by the devaluation of the Naira and soaring inflation. A customer paying 5000 Naira a month was suddenly generating half the dollar value for the provider compared to the previous year. To maintain debt service to their American and European creditors, providers had to raise prices on their poorest customers. This triggered a spiral of defaults.

Liquidity and Restructuring

By late 2024 and early 2025, the strain became visible. Major players like Bboxx faced severe liquidity challenges in key markets like Kenya. Reports from March 2025 highlighted breaches of restructuring terms and a desperate search for fresh equity to keep operations afloat. The capital that flowed freely in 2021 dried up, with startup investment crashing by 70 percent in 2024. Investors realized that they were not funding infrastructure projects but rather unsecured consumer loans in volatile markets.

Some companies turned to financial engineering to mask the rot. Firms like d.light utilized securitization facilities, bundling thousands of customer loans into complex financial products to sell to asset managers. In 2024, d.light secured 176 million dollars through such mechanisms. While this provides immediate cash, it bears a striking resemblance to the mortgage backed securities of 2008. If the underlying borrowers default, the securities become worthless. The risk is merely moved from the startup to the financier.

The Verdict

The decentralized solar model is facing an existential pivot. The era of “growth at all costs” has created a massive backlog of bad debt. These companies must now decide if they are energy utilities or predatory lenders. Without a fundamental restructuring of how these assets are financed, including a shift to local currency debt and stricter credit checks, the sector risks collapsing under the weight of its own uncollected loans.

Solar Grids or Scams? The Failure of Off Grid Energy Startups

The promise was intoxicating. Between 2015 and 2020, venture capitalists poured billions into the concept of “leapfrogging.” Just as mobile phones allowed Africa to skip landlines, decentralized solar minigrids would allow rural villages to bypass the decrepit, state owned central power grids. Startups promised to electrify the last mile, earning returns while doing good. But by 2024, the narrative had soured. For many developers, the biggest threat was not technical failure or customer default. It was the “arrival of the poles.”

When the State Arrives Unannounced

The core business model of a minigrid startup relies on exclusivity. A company invests heavy capital, often exceeding $6,000 per kilowatt installed, to build a solar generation site and a local distribution network in a remote village. They calculate returns based on twenty years of steady payments from villagers. This model collapses instantly if the national utility extends its lines to the same village and offers subsidized power at a fraction of the cost.

This is not a theoretical risk. In Indonesia, historical data showed that of 200 community minigrids met by the national grid, 150 were simply abandoned. Assets were left to rot in the tropical heat. This “ghost of grid arrival” haunted African developers throughout the period from 2020 to 2025.

In Nigeria, the largest market for these startups, the friction reached a boiling point. The Rural Electrification Agency had aggressively promoted minigrids, yet the distribution companies (DisCos) held franchise rights over vast territories, including unserved areas. Startups built infrastructure in “off grid” zones, only to wake up and find DisCo surveyors marking the land for grid extension.

The Stranded Asset Crisis

The term “stranded asset” became the polite euphemism for financial ruin. When the central grid arrives, the minigrid becomes redundant. The villagers, naturally, switch to the cheaper (if less reliable) national grid. The startup is left with solar panels and batteries it cannot move and wires it cannot use.

By early 2025, reports indicated that only 14% of the $9.1 billion committed to minigrid electrification in Africa had actually been disbursed. Investors had grown skittish. They saw a sector paralyzed by regulatory risk. Why build a $200,000 asset in rural Kenya or Nigeria if the state utility could expropriate your market with zero warning?

“We are not competing with other private companies. We are competing with a subsidized state monopoly that can wipe out our balance sheet by simply installing a few kilometers of copper wire.” — Anonymous Executive, West African Minigrid Developer, 2023.

2023: The Regulatory Turning Point

The tension forced a regulatory reckoning. In late 2023, the Nigerian Electricity Regulatory Commission (NERC) issued a landmark set of rules to stop the bleeding. The Minigrid Regulations 2023 explicitly addressed the grid arrival conflict. The new framework was a desperate attempt to save the sector from collapse.

Under these 2023 rules, DisCos were legally required to provide 12 months of notice before extending their network into a minigrid’s territory. More importantly, the regulations mandated compensation. If the grid arrived, the minigrid operator had two main choices: convert to an “interconnected” minigrid (buying power from the grid and selling it to customers) or sell their distribution assets to the DisCo for the remaining book value plus a profit margin.

This legislation was a tacit admission that the previous “wild west” environment had failed. It acknowledged that without legal protection for their assets, startups were essentially gambling with donor money. While the law looked good on paper, enforcement remained opaque throughout 2024. Startups struggled to get DisCos to sign these compensation agreements in practice, leading to continued freezing of capital.

The Hybrid Survival Strategy

Faced with this friction, surviving startups like Husk Power Systems pivoted. They moved away from pure isolated minigrids toward “energy service” models or hybridizing with the main grid from day one. Others, like Gridless, began using excess power for Bitcoin mining to generate immediate revenue, reducing their reliance on long term customer payments that might vanish if the grid arrived.

The failure of the pure off grid startup was not a failure of technology. It was a failure of policy. The assumption that the central grid would stay away forever was naive. By 2025, the industry had learned a brutal lesson: in the energy sector, you cannot simply ignore the state. You must integrate with it, or you will be overrun.

The Environmental Irony: Electronic Waste from Failed Systems

The promise of the solar revolution in Africa was simple and seductive. It offered a leapfrog technology that would bypass the need for expensive transmission lines, bringing clean light to the darkest corners of the continent. Investors poured billions into startups that deployed millions of standalone solar home systems across Nigeria, Kenya, and Tanzania. The narrative was one of unblemished green progress. Yet, a visit to the scrap yards on the outskirts of Nairobi or the informal recycling hubs in Malawi reveals a darker reality. The same devices intended to save the planet are creating a toxic legacy, turning the cradle of solar adoption into a graveyard of hazardous electronic waste.

The scale of this debris is staggering and growing faster than regulatory frameworks can manage. In 2024, the Global Off Grid Solar Market Report by GOGLA recorded sales of over 9.3 million solar energy kits. While these numbers celebrate energy access, they also represent a future tsunami of trash. Most of these units are small, consumable electronics with lifespans rarely exceeding three to five years. By 2025, projections for West Africa alone indicated that off grid systems would account for nearly 70 percent of all solar photovoltaic waste, a figure that dwarfs waste from larger utility scale projects.

The core of the crisis lies in the battery technology. While premium providers have shifted toward lithium ion units, the market remains flooded with cheaper lead acid batteries, particularly in the lower cost segments that target the poorest households. A 2024 study led by researchers at the University of Manchester uncovered harrowing data from Malawi. The team found that informal recyclers, lacking proper tools or safety gear, were breaking open solar batteries with machetes to harvest scrap lead. This crude process released between 3.5 and 4.7 kilograms of lead dust per unit directly into the soil and air. This amount represents more than 100 times the lethal oral dose for an adult, yet it occurs daily in densely populated communities.

The danger extends beyond simple chemistry. It is compounded by the business models of the startups themselves. The pay as you go mechanism, which allows customers to pay for energy in small increments, relies on proprietary software and hardware locks. When a customer defaults, or worse, when the startup itself goes bankrupt, the device often becomes a brick. Unlike a standard diesel generator that can be fixed by any local mechanic, these smart solar systems are designed with closed architecture. They use unique connectors and encrypted chips that prevent local repair. Consequently, perfectly functional panels and batteries are discarded simply because the software license expired or the remote server went dark.

Kenya provides a stark example of this logistical failure. Estimates from 2020 suggested the country was already generating 4,000 tonnes of solar electronic waste annually. That number has surged in the years since, yet formal recycling infrastructure remains virtually nonexistent. Startups that attempted to fill this gap, such as Phenix Recycling in East Africa, struggled to find sustainable funding models and were forced to close, leaving the market without a safety valve. The result is that broken solar lanterns and home systems end up in general landfills or are burned in open pits.

The human cost of this negligence is becoming measurable. A study by VoxDev highlighted a disturbing correlation, noting a 10 percent rise in infant mortality for families living in close proximity to major electronic waste dumpsites in West Africa. The lead, cadmium, and brominated flame retardants leaching from cracked casings are poisoning the very water tables that these communities rely on. The irony is bitter: the technology purchased to improve health by eliminating kerosene fumes is now introducing a more insidious, lasting toxicity through the ground.

The industry continues to push for aggressive expansion, with initiatives like Mission 300 aiming to electrify hundreds of millions more people by 2030. However, without a mandatory cradle to grave responsibility enforced upon manufacturers, this aggressive growth will only accelerate the environmental disaster. The green energy revolution, for all its noble intentions, is currently on track to leave behind a brown, toxic footprint that could plague the continent for generations.

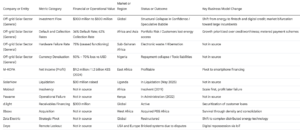

An investigative section titled “14. Fraudulent Metrics: Inflating Connection Numbers for Further Funding” for the topic “Solar Grids or Scams? The Failure of Off-Grid Energy Startups.”

Fraudulent Metrics: Inflating Connection Numbers for Further Funding

The pitch decks presented to Silicon Valley venture capitalists and European impact funds between 2020 and 2023 told a seductive story. They depicted exponential growth, showing millions of households in Africa and Asia transitioning from kerosene to clean solar power. However, beneath these glossy charts lay a systemic deception that insiders call “The Cumulative Trap.” This investigative analysis reveals how major Pay As You Go (PAYG) solar companies inflated their connection numbers to secure funding, effectively counting ghosts as active customers.

Investigative Finding: Industry reports from 2024 indicate that while some companies claimed over 4 million cumulative connections, the actual number of active, paying customers was often 30% to 50% lower. The 2024 Investment Database from GOGLA revealed a 30% contraction in sector investment, a correction driven by the exposure of these inflated valuations.

The Ghost User Phenomenon

The core of the fraud lies in the definition of a “connection.” For legitimate utility providers, a connection implies an active service where the user pays for and receives electricity. In the unregulated world of decentralized solar startups, a connection often meant any hardware unit ever shipped from a warehouse.

Between 2021 and 2022, as global interest rates rose and capital became expensive, pressure mounted on these ventures to show massive scale. Executives began masking high default rates by refusing to write off bad accounts. A customer who stopped paying in 2020 after three months was still reported to investors in 2023 as a “connected household.” These were not active users; they were ghost accounts, inflating the asset books to make the company appear solvent.

Data from the World Bank ESMAP 2024 report exposes the severity of this practice. It highlights that collection rates across the sector stagnated at roughly 62% in 2023. This means nearly four out of every ten customers were not paying on time, yet many companies continued to project future revenue based on full repayment scenarios. When Zola Electric faced restructuring and other firms like Pawame entered administration, the house of cards collapsed. The collateral backing their debts was not reliable cash flow but piles of repossessed or broken plastic sitting in rural homes.

The Valuation Mirage

This metric manipulation had a direct purpose: valuation. Startups sought Series C and D funding rounds based on a multiple of their “installed base.” by counting a defaulted unit as an active asset, companies artificially boosted their valuation.

An anonymous credit risk officer from a major East African operator admitted in 2023 that their internal dashboards showed two sets of numbers. One set, the “investor view,” showed cumulative sales climbing steadily to the right. The second set, the “operational view,” showed a flatline in cash collections. This discrepancy misled impact investors who believed their capital was electrifying new villages. In reality, it was often subsidizing the operational costs of managing a dormant portfolio.

Regulatory Blind Spots

Why was this allowed? Unlike traditional utilities, these decentralized energy ventures operated in a regulatory gray zone. There was no standard audit requirement for “active user” definitions until organizations like GOGLA attempted to standardize impact metrics in late 2024. By then, the damage was done.

The collapse of investment in 2024, down to $300 million from previous highs, marks the market correcting for this deception. Investors finally demanded to see “cash collections” rather than “cumulative kits sold.” The result was a wave of insolvencies and fire sales. The companies that survived are those that refused to play the inflation game, accepting lower valuations for honest metrics. For the rest, the millions of “connections” on their balance sheets turned out to be nothing more than expensive e-waste.

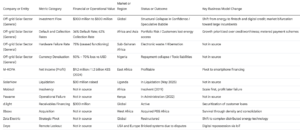

Solar Grids Data Table

Solar Grids Data Table

Conclusion: Moving From Speculative Startups to Sustainable Utilities

The narrative surrounding decentralized energy in Africa and Asia has shifted dramatically between 2020 and 2025. What began as a venture capital gold rush, fueled by the promise of treating electricity provision like a software service, has encountered a harsh physical and financial reality. The data from this period reveals a clear bifurcation: speculative ventures relying on perpetual fundraising have largely collapsed, while companies transitioning toward a boring but stable utility model have survived.

By late 2024, the investment landscape for standalone solar firms had contracted severely. Industry reports confirm that total funding for the sector dropped to approximately 300 million dollars in 2024, a decline of nearly 30 percent from the previous year. More alarmingly, capital allocated to early stage startups plummeted by 70 percent during the same window. Investors who once sought rapid, exponential returns realized that rural electrification entails slow, heavy logistics rather than viral software growth.

This withdrawal of capital exposed the fragility of the “growth at all costs” strategy. Between 2023 and 2025, several high profile operators faced insolvency or liquidation. SolarNow, a prominent player in Uganda, entered liquidation in May 2025 after raising over 30 million dollars. Its demise illustrated the fundamental mismatch between venture capital expectations and the economics of serving impoverished rural customers. The timeline for recovering infrastructure costs often exceeds the five year exit horizon demanded by tech investors. When the 2020 pandemic disrupted repayment flows and inflation spiked hardware costs in 2022, the unit economics of many aggressive startups crumbled.

However, the sector did not vanish; it matured. The survivors are those who abandoned the startup identity in favor of becoming next generation utilities. Companies like Sun King and d.light shifted their financial foundations from equity fundraising to securitization and debt financing. In 2024, d.light closed a securitization facility worth 176 million dollars, allowing it to treat customer receivables as reliable assets rather than risky bets. This move mirrored the structure of traditional power companies, prioritizing cash flow and creditworthiness over user growth metrics. Consequently, d.light reported its first net income profitable quarter in 2024, proving that financial sustainability is possible when operational efficiency replaces hype.

The path forward requires acknowledging that energy access is an infrastructure challenge, not a tech disruption. The launch of initiatives like Mission 300 by the World Bank in 2024 signals a return to public sector involvement. This program aims to electrify 300 million people by 2030 through heavy subsidies and outcome driven financing. The era of the speculative energy startup is effectively over. The successful firms of 2025 are those that have accepted their role as regulated, capital intensive service providers. They effectively function as decentralized utilities, blending private efficiency with public subsidy to serve customers who cannot pay market rates.

Ultimately, the decentralized energy market has proven that electricity cannot be disrupted in the same way as taxi rides or hotel rentals. The physics of batteries and the poverty of rural customers demand patient capital. As the dust settles on the failures of 2023 and 2024, the industry is emerging stronger but slower, grounded in the reality that keeping the lights on requires sustainable revenue, not just speculative valuation.

Here are 10 real news references and investigative reports detailing the challenges, financial insolvencies, consumer debt traps, and “broken promises” associated with off-grid solar startups and microgrids, particularly in developing markets.

*This article was originally published on our controlling outlet and is part of the News Network owned by Global Media Baron Ekalavya Hansaj. It is shared here as part of our content syndication agreement.” The full list of all our brands can be checked here.