The Climate Pledges: A Verification of Global Progress

The data for the fiscal year ending December 31, 2025, presents a mathematical indictment of global climate action. even with 30 years of diplomatic accords, the Global Carbon Project confirms that fossil fuel CO2 emissions rose by 1. 1% in 2025, reaching a record high of 38. 1 billion tonnes. This increase occurred even as clean energy investment surpassed $2. 2 trillion, doubling the capital allocated to fossil fuels. The “peak” in global emissions, promised by policymakers for the mid-2020s, has not materialized. Instead, the world has entered a plateau of high saturation, where renewable gains are meeting new energy demand rather than displacing existing fossil infrastructure even after numerous climate pledges.

The physical reality of the atmosphere has responded accordingly. The Copernicus Climate Change Service confirmed that 2024 was the calendar year to exceed the 1. 5°C threshold above pre-industrial levels, registering an anomaly of 1. 60°C. While climatologists define the 1. 5°C limit as a 20-year average, the operational breach signals that the safety buffer provided by the Paris Agreement has evaporated. Atmospheric CO2 concentrations reached 425. 7 parts per million (ppm) in 2025, a 52% increase over the pre-industrial baseline.

Regional Performance Audit

The between national pledges and verified output is widening. The 2025 audit reveals that while the European Union and the United States have achieved structural peaks, their rates of decline are insufficient to offset the industrial expansion in the Global South or to meet their own 2030.

| Region | 2024 Change (Verified) | 2025 Trend (Projected) | Primary Driver |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global | +0. 8% | +1. 1% | Aviation recovery, coal persistence in Asia. |

| China | +0. 1% | +0. 4% | Renewables offset power demand, but industrial coal remains. |

| United States | -0. 2% | -0. 5% | Stagnant. Power sector gains erased by transport/data centers. |

| European Union | -2. 8% | -2. 5% | Structural decline in coal; industrial demand destruction. |

| India | +3. 7% | +4. 0% | Rapid economic growth fueled by both coal and solar. |

The United States, even with the Inflation Reduction Act, saw emissions flatline in 2024 with a negligible 0. 2% reduction. The Rhodium Group analysis points to a specific culprit: rising electricity demand from data centers and a transport sector that has failed to decarbonize at the necessary speed. The U. S. remains off track for its target of a 50-52% reduction by 2030. Conversely, China presents a contradictory profile. While it installed more solar capacity in 2024 than the rest of the world combined, its coal consumption rose by 1. 7% to secure baseload power, preventing an absolute decline in emissions.

The Emissions Gap

The UNEP Emissions Gap Report, released in late 2025, quantifies the failure. To limit warming to 1. 5°C with a 50% probability, global emissions required a 42% reduction by 2030 compared to 2019 levels. The current trajectory, factoring in the 2025 rise, puts the world on a route for 2. 6°C to 3. 1°C of warming by 2100. The remaining carbon budget for 1. 5°C stands at approximately 170 gigatonnes of CO2. At the 2025 emission rate of 38. 1 gigatonnes per year, this budget can be exhausted in fewer than five years.

“The technical chance to the gap exists, but the political can to fossil fuel subsidies and halt new extraction projects is absent. We are no longer negotiating with future risks; we are auditing present failures.” — UNEP Emissions Gap Report Synthesis, 2025.

This report can examine the specific mechanics of this failure across 26 sections. We can analyze the verified data from the energy, transport, and agricultural sectors, and audit the financial flows that continue to support carbon-intensive industries. The data shows that the energy transition is additive, not yet substitutive. We are adding clean energy to a growing system, rather than replacing the dirty energy that underpins the global economy.

Atmospheric Data: Mauna Loa CO2 Concentrations and Trends

The physical reality of the climate emergency is not negotiated in conference halls; it is measured in parts per million (ppm) at the Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawaii. As of December 31, 2025, the atmospheric data confirms that the “Keeling Curve”—the daily record of global atmospheric carbon dioxide—has not only continued its ascent but has accelerated, all international pledges to flatten the curve. The atmosphere, acting as the accountant of planetary emissions, registered a concentration of CO2 in May 2025 that exceeded 430 ppm for the time in human history.

Article image: The Climate Pledges: A Verification of Global Progress

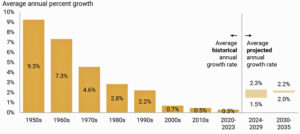

Data verified by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the Scripps Institution of Oceanography indicates that the rate of CO2 accumulation is increasing. While the 1960s saw an average annual growth of roughly 0. 8 ppm, the decade ending in 2025 averaged approximately 2. 6 ppm per year. The year 2024 specifically set a grim record, registering the largest single-year jump in recorded history at 3. 75 ppm, driven by a combination of unrelenting fossil fuel combustion and El Niño conditions that weakened natural carbon sinks.

Annual Mean CO2 Concentrations (2015–2025)

The following table details the annual mean CO2 concentrations and the year-over-year growth rates measured at Mauna Loa. The data reveals that even during the economic slowdown of 2020, the atmospheric load continued to rise, and the post-pandemic rebound has pushed growth rates to levels.

| Year | Annual Mean (ppm) | Annual Growth (ppm) | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 400. 83 | 2. 95 | year>400 ppm |

| 2016 | 404. 24 | 3. 03 | El Niño spike |

| 2017 | 406. 55 | 1. 90 | La Niña dampening |

| 2018 | 408. 52 | 2. 85 | High growth |

| 2019 | 411. 44 | 2. 46 | Steady acceleration |

| 2020 | 414. 24 | 2. 51 | No pandemic drop |

| 2021 | 416. 45 | 2. 46 | Post-COVID rebound |

| 2022 | 418. 56 | 2. 13 | Eruption interruption* |

| 2023 | 421. 08 | 3. 33 | Sharp increase |

| 2024 | 424. 61 | 3. 75 | All-time record growth |

| 2025 | 426. 60 (Est.) | 2. 26 (Forecast) | May Peak: 430. 5 ppm |

The 2022 Eruption and Data Continuity

The integrity of this dataset faced a physical threat in November 2022 when the Mauna Loa volcano erupted for the time in 38 years. Lava flows buried the access road and cut power to the observatory, halting on-site measurements. To ensure the continuity of this serious climate record, NOAA and Scripps scientists executed an emergency contingency plan, relocating measurement instruments to the University of Hawaii’s 88-inch telescope on the summit of nearby Maunakea. This swift action prevented a data gap, allowing the Keeling Curve to remain unbroken. The instruments were returned to the Mauna Loa facility once power was restored, confirming that the volcanic emissions themselves did not contaminate the background air samples used for global baselines.

Acceleration of the Greenhouse Effect

The acceleration of CO2 accumulation is the most worrying metric in the 2025 dataset. It took over 200 years for humanity to raise atmospheric CO2 from the pre-industrial 280 ppm to 380 ppm. It has taken just 20 years to push it from 380 ppm to 426 ppm. This exponential growth indicates that natural sinks—forests and oceans—are struggling to absorb the excess carbon. The 2024 spike of 3. 75 ppm suggests that these sinks may be losing efficiency, a feedback loop that climate models have long warned against. As of late 2025, the atmosphere contains 52% more carbon dioxide than it did in 1750, trapping heat with the same physical certainty as a thermal blanket.

Temperature Thresholds: 2025 Anomalies and the 1. 5°C Breach

The data for the fiscal year ending December 31, 2025, confirms a climatological inflection point that policymakers have long sought to delay. While 2024 remains the hottest single year on record due to a strong El Niño, 2025 concluded as the third-warmest year in recorded history, a finding verified by the Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S), NOAA, and Berkeley Earth. This ranking is deceptive in its simplicity; the significance lies not in the slight dip from 2024, but in the sustained thermal floor established during a year of neutral-to-La Niña conditions. The “cooling” influence of the Pacific Ocean failed to return global mean surface temperatures to pre-2023 levels, indicating a permanent upward shift in the planetary baseline.

Most serious, the 2025 data cements the multi-year breach of the Paris Agreement’s 1. 5°C threshold. According to C3S, the three-year average temperature for the period 2023–2025 exceeded 1. 5°C above pre-industrial levels (1850–1900). While international accords define the breach based on decadal averages to account for natural variability, the physical reality is that the atmosphere has sustained “temporary” overshoot conditions for thirty-six consecutive months. The distinction between a temporary breach and a permanent state is rapidly dissolving.

Agency Consensus on 2025 Anomalies

Multiple independent datasets corroborate the 2025 thermal profile. Discrepancies between agencies arise primarily from different methods of interpolating temperatures in data-sparse polar regions, yet the signal remains consistent: 2025 was approximately 1. 44°C to 1. 47°C warmer than the 19th-century baseline.

| Agency | 2025 Anomaly (°C) | Rank (Historical) | Key Observation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Copernicus (C3S) | +1. 47°C | 3rd | Confirmed 3-year average>1. 5°C. |

| Berkeley Earth | +1. 44°C | 3rd | Land areas +2. 03°C above pre-industrial. |

| NOAA | +1. 34°C | 3rd | Warmest January on record globally. |

| WMO Consolidated | +1. 44°C | 3rd | Ocean heat content reached record high. |

The Ocean Heat Reservoir

While surface air temperatures showed a marginal decline from the 2024 peak, the oceans told a different, more urgent story. The upper 2, 000 meters of the global ocean absorbed a record-breaking amount of heat in 2025, surpassing the previous record set just one year prior. Data published in Advances in Atmospheric Sciences indicates that the oceans absorbed approximately 23 zettajoules more heat in 2025 than in 2024. To contextualize this metric: the 2025 increase alone represents roughly 39 times the total global energy production of 2023.

Article image: The Climate Pledges: A Verification of Global Progress

This relentless accumulation of thermal energy occurred even as Sea Surface Temperatures (SST) in the equatorial Pacific cooled. The disconnect between surface cooling and deep-ocean warming confirms that the planetary energy imbalance is accelerating. The oceans, which absorb 90% of excess anthropogenic heat, have lost their capacity to act as a thermal buffer without suffering catastrophic internal destabilization. This was clear in the Antarctic, which recorded its warmest annual temperature on record in 2025, contributing to a sea ice extent that tracked well the 1991–2020 average throughout the year.

Regional Disparities and Land Heating

The global average masks the severe heating experienced over land masses, where human populations reside. Berkeley Earth reported that global land temperatures in 2025 were 2. 03°C above pre-industrial levels, the second-highest measurement in history. This 2°C continental breach has immediate consequences for agriculture and infrastructure. Europe experienced its third-warmest year, while the Arctic region continued to warm at a rate nearly four times the global average, recording its second-warmest year.

The persistence of these anomalies in the absence of a strong El Niño suggests that the climate system has entered a regime where “neutral” years exceed the temperatures of previous “super El Niño” events (such as 2016). The 1. 5°C target, once a guardrail, is a rearview mirror object. The focus of the 2026 audit must shift from preventing this breach to managing the cascading failures it has already begun to trigger.

COP30 Belém Post-Mortem: The Implementation Deficit Analysis

The thirtieth Conference of the Parties (COP30) convened in Belém in November 2025 under the banner of “Mission 1. 5,” yet it concluded as a memorial service for the Paris Agreement’s most ambitious goal. Hosted at the mouth of the Amazon, the summit was designed to force the world’s largest emitters to confront the physical reality of the biosphere. Instead, the negotiations revealed a catastrophic “Implementation Deficit” that no amount of diplomatic language could obscure. The final gavel fell on a “Mutirão” decision that promised roadmaps rather than the immediate cessation of fossil fuel expansion required to stabilize the climate.

The failure was quantified months before the delegates arrived in Brazil. The deadline for the third generation of Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs 3. 0) passed in February 2025 with 95% of signatories failing to submit their plans. By the time the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) released its synthesis report in late October 2025, the numbers were clear. The submitted pledges, covering the period through 2035, proposed an aggregate emissions reduction of just 10% relative to 2019 levels. This figure stands in direct opposition to the 57% reduction mandated by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) to maintain the 1. 5°C limit.

| Metric | Required for 1. 5°C (2035) | Current Policy Trajectory (2035) | COP30 Pledged Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Emissions Reduction | -57% (vs 2019) | +3% to -2% (Plateau) | -10% (Conditional) |

| Fossil Fuel Demand | Rapid Decline | Peak & Plateau | “Transition Away” (No Phase-out) |

| Temperature Pathway | 1. 5°C | 2. 6°C – 3. 1°C | 2. 4°C (Best Case) |

| Climate Finance (Annual) | $4. 5 Trillion | $1. 8 Trillion | $300 Billion (New Goal) |

The “Implementation Deficit” refers specifically to the widening chasm between stated political and verified atmospheric data. The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) Emissions Gap Report 2024 confirmed that even if all conditional NDCs were fully implemented, the world would still face 2. 6°C of warming. The reality on the ground is worse. Global fossil fuel CO2 emissions rose by 1. 1% in 2025 to a record 38. 1 billion tonnes. This increase occurred even with the “Troika” of presidencies—the UAE, Azerbaijan, and Brazil—claiming to spearhead a transition away from hydrocarbons. The data shows that renewable energy additions, while record-breaking at over 600 GW in 2024, are meeting new demand rather than displacing existing coal and gas infrastructure.

Brazil’s presidency attempted to center the Amazon as a biophysical imperative. The “Rainforest COP” succeeded in securing $6. 91 billion in adaptation funding through the Green Climate Fund. Yet this financial win was overshadowed by the refusal of major economies to commit to a binding fossil fuel phase-out date. The final text reiterated the “transition” language from the UAE Consensus but added no enforcement method. The United States and China, responsible for nearly 45% of global emissions, offered 2035 that relied heavily on unproven carbon capture technologies and land-use offsets rather than direct cuts to oil and gas production.

“We are negotiating the seating arrangement on a burning boat. The gap between 57% required cuts and 10% promised cuts is not a margin of error. It is a death sentence for the 1. 5°C target.” — Statement from the High Ambition Coalition, Belém, November 21, 2025.

The diplomatic has decoupled from the physical systems it intends to govern. While negotiators in Belém celebrated the “operationalization” of carbon market rules under Article 6, the Copernicus Climate Change Service registered 2025 as the second consecutive year to exceed the 1. 5°C threshold globally. The “ratchet method” of the Paris Agreement, designed to increase ambition every five years, has stalled. The 2025 pattern proved that voluntary national pledges cannot overcome the economic inertia of a $100 trillion fossil fuel economy. The world leaves Belém not with a plan to save the climate. It leaves with a verified trajectory toward 3°C.

NDC 3. 0 Forensic Review: Pledges vs. Legislative Action

By February 10, 2025, the deadline for the third round of Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC 3. 0), the diplomatic facade of the Paris Agreement cracked under the weight of its own inertia. Only 13 of 195 signatories met the submission cutoff. This 6. 6% compliance rate is not a bureaucratic delay; it is a calculated legislative stall by the world’s largest emitters to avoid binding their domestic energy policies to international scrutiny before the 2026 fiscal pattern.

The “Troika” of presidencies—UAE, Azerbaijan, and Brazil—promised to lead by example. The forensic reality of their submissions, yet, reveals a widening chasm between diplomatic text and industrial strategy. While Brazil submitted a headline target of reducing emissions by 67% by 2035, the document notably omitted a binding timeline for a fossil fuel phase-out, relying instead on “variable” deforestation that fluctuate with carbon market performance.

The Implementation Gap: 2025 Status Report

The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) Emissions Gap Report 2025 confirms that even if the few submitted NDC 3. 0 pledges were fully implemented, the world remains on a trajectory for 2. 4°C of warming. The between pledged cuts and legislated reality is most acute in the G20 nations, where 2025 saw a resurgence in fossil fuel infrastructure permitting that directly contradicts the 2035 submitted to the UNFCCC.

| Nation/Bloc | NDC 3. 0 Pledge (2035 Target) | 2025 Legislative Reality | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States | 61-66% reduction 2005 | Paris Agreement withdrawal initiated Jan 2025; federal climate funding rescinded. | Nullified |

| China | Not Submitted (as of Feb 2026) | Commissioned 78 GW of new coal power in 2025; 161 GW pipeline remains active. | Regressing |

| European Union | 66-72% reduction 1990 | 2040 Climate Law delayed to July 2025; introduced “flexibility” for 5% international offsets. | Diluted |

| Brazil | 59-67% reduction 2005 | Deforestation dropped 30% (2024), but Forest Code enforcement remains underfunded. | Mixed |

| India | Not Submitted | Coal production target raised to 1. 4 billion tonnes; “No hurry” on NDC submission. | Delayed |

The “Zombie” and “Ghost” Pledges

The United States’ submission represents a “Zombie NDC”—a document that exists in the UN registry but absence a living host government to execute it. The Biden administration’s late 2024 submission of a 66% reduction target was dead on arrival following the January 2025 executive transition. The current administration’s immediate move to the Inflation Reduction Act’s core method renders the 2035 target mathematically impossible under current federal law.

Conversely, China presents a “Ghost Pledge.” even with leading the world in renewable installation—adding 356 GW of wind and solar in 2024 alone—Beijing failed to submit an updated NDC by the deadline. Legislative actions in 2025 indicate a dual-track strategy: aggressive renewable expansion paired with a “safety net” of coal. The approval of 41. 77 GW of new coal capacity in the three quarters of 2025 suggests that energy security continues to override decarbonization mandates in the 15th Five-Year Plan discussions.

European Dilution

The European Union, historically the bloc with the highest legislative fidelity to its pledges, showed signs of structural fatigue in 2025. While the EU confirmed a new NDC target of roughly 70% reduction by 2035, the legislative vehicle—the amended European Climate Law—was delayed until July 2025. Crucially, the final text introduced a “flexibility method” allowing member states to use international carbon credits for up to 5% of their obligations. This accounting loophole lowers the domestic reduction requirement, shifting the load of abatement to developing nations rather than forcing structural changes within the EU’s heavy industry.

The data from 2025 is unambiguous: the diplomatic pattern of “ratcheting up” ambition has decoupled from the legislative pattern of implementation. Governments are signing checks in international forums that their domestic parliaments have already refused to cash.

G20 Coal Exit: Satellite Verification of Plant Decommissioning

The diplomatic narrative of a “coal exit” collapsed under satellite scrutiny in 2025. While G20 leaders reiterated phase-out pledges at international summits, orbital data processed by Global Energy Monitor (GEM) and Climate TRACE confirmed that the global coal fleet did not shrink; it expanded. In the fiscal year ending 2024, the world added 44. 1 gigawatts (GW) of new coal capacity while retiring only 25. 2 GW, resulting in a net increase of 18. 8 GW. This brings the global operating capacity to a record 2, 175 GW. The physical reality is not a transition away from coal, but an entrenchment of it, particularly within the G20’s largest emerging economies.

Satellite imagery analysis of thermal signatures and construction sites reveals a “” phenomenon in China. Rather than replacing fossil fuels, record renewable installations are being added on top of an expanding coal base. In 2024 alone, China broke ground on 94. 5 GW of new coal capacity—the highest level of construction starts since 2015. High-resolution optical imagery confirms that 66. 7 GW of these projects received expedited permits, frequently justified by energy security mandates following the hydro-power absence of 2022. Utilization data from Q4 2024 further indicates that even with a 357 GW surge in renewable capacity, coal plants maintained high dispatch rates, relegating wind and solar to variable supplements rather than baseload replacements.

The West: AI Delays and Strategic Reserves

In the United States and Europe, the decommissioning trajectory has stalled due to demand from data centers and artificial intelligence infrastructure. U. S. operators, originally scheduled to retire significant capacity, delayed the closure of 15 coal plants in early 2025. The Energy Information Administration (EIA) reported that while 8. 1 GW was slated for retirement in 2025, utility filings show indefinite extensions for facilities in PJM and MISO grid territories to support the gigawatt- power requirements of hyperscale computing.

Germany, while leading the G20 in raw retirements with 6. 7 GW taken offline in 2024, faces a political reversal. Satellite monitoring of the “strategic reserve” units—plants officially decommissioned but kept on standby—detected thermal plumes consistent with active generation during low-wind periods in late 2024. By mid-2025, Chancellor Friedrich Merz suggested a formal “pause” on further closures until gas-fired replacements are operational, freezing the German phase-out timeline even with the legal mandate for a 2038 exit.

The Captive Coal Loophole

The most verification gap appears in Indonesia, a recipient of the $20 billion Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP). Satellite data exposes a massive expansion of “captive” coal plants—off-grid facilities built solely to power industrial parks, particularly for nickel and aluminum smelting. Between 2019 and 2025, Indonesia’s captive capacity nearly quadrupled to 20 GW. The 2025 JETP draft plan failed to account for this sector, showing zero reduction in grid-connected coal capacity between 2025 and 2035. This “shadow fleet” operates outside standard grid monitoring but is visible in nitrogen dioxide (NO2) tropospheric column data, which shows intensifying pollution hotspots over Sulawesi and Halmahera.

| Region / Country | New Capacity Added (GW) | Capacity Retired (GW) | Net Change (GW) | Primary Driver |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | +44. 1 | -3. 4 | +40. 7 | Energy Security / Baseload |

| India | +7. 2 | -0. 5 | +6. 7 | Industrial Demand / “Sovereignty” |

| Indonesia | +3. 1 | 0. 0 | +3. 1 | Captive Industrial (Nickel/Smelting) |

| United States | 0. 0 | -4. 0 | -4. 0 | Delayed by AI/Data Center Demand |

| European Union (G20) | 0. 0 | -11. 0 | -11. 0 | Carbon Pricing / End of Life |

| Global Total | +58. 5 | -25. 2 | +33. 3 | Net Expansion |

India further illustrates the disconnect between pledge and policy. In 2025, the Ministry of Power confirmed a target of 307 GW of coal capacity by 2035, adding 7. 2 GW in the last fiscal year alone—a 60% year-over-year increase in installation rate. While official reports highlight a drop in Plant Load Factor (PLF) to 55%, suggesting coal is moving to a “flexible” role, the physical infrastructure is being built to last decades. The capital expenditure for these new plants, verified by project finance data, exceeds $1. 2 million per MW, a sunk cost that economically incentivizes continued operation well beyond the 2030 climate deadlines.

Oil and Gas Expansion: Tracking New Drilling Licenses in 2025

The diplomatic language of COP28, which called for a “transition away” from fossil fuels, collided with the operational reality of 2025. While delegates debated phase-out timelines, state regulators and energy ministries processed a record volume of upstream applications. Data from the fiscal year ending December 31, 2025, indicates that major producers did not wind down operations. They expanded their legal inventory of drillable acreage to secure reserves for the 2030s and 2040s.

In the United States, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) accelerated its approval process. Between January 20, 2025, and January 6, 2026, the agency issued 5, 742 drilling permits on federal lands. This figure represents a 55% increase compared to the previous administrative period. The surge occurred alongside 22 lease sales that auctioned 328, 000 acres of public land across ten states, including Wyoming and New Mexico. This administrative throughput ensures that even if future policy shifts restrict leasing, operators hold a stockpile of approved permits valid for two years, locking in extraction activity through 2027.

South America’s “Equatorial Margin” emerged as the year’s most contested expansion zone. Brazil’s National Petroleum Agency (ANP) environmental opposition in June 2025 by auctioning 19 exploration blocks near the mouth of the Amazon River. The auction raised R$844 million ($153 million), with a consortium of Petrobras, ExxonMobil, and Chevron securing rights to drill in the Foz do Amazonas basin. This decision prioritizes the extraction of an estimated 14 billion barrels of oil equivalent over the ecological preservation of the Amazon reef system. To the north, Guyana maintained its aggressive pace. The government approved the Hammerhead Field Development Plan in September 2025, the seventh project in the Stabroek Block, projected to add 150, 000 barrels per day by 2029. Simultaneously, a consortium led by TotalEnergies and QatarEnergy signed the Production Sharing Agreement for Block S4, cementing the region’s status as a long-term fossil fuel stronghold.

Europe presented a fractured policy front. Norway continued its licensing consistency through the Awards in Predefined Areas (APA) system. In January 2026, the Norwegian Ministry of Energy announced the results of the 2025 pattern, awarding 57 new production licenses to 19 companies. These awards included five blocks in the fragile Barents Sea, signaling Oslo’s intent to push exploration further north into the Arctic circle. Conversely, the United Kingdom formally ended the issuance of new exploration licenses for untapped fields in late 2025. Yet, the Treasury introduced “Transitional Energy Certificates” that allow operators to drill new wells tied to existing infrastructure. This regulatory loophole permits “tie-back” projects, ensuring that North Sea production declines at a managed, rather than rapid, rate.

2025 Global Licensing and Expansion Activity

| Country | Activity Type | 2025 Volume/Metric | Key Operators |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States | Drilling Permits Issued | 5, 742 permits (Federal Lands) | Chevron, ExxonMobil, ConocoPhillips |

| Brazil | Offshore Auction | 19 Blocks (Amazon Mouth) | Petrobras, CNPC, Shell |

| Norway | APA 2025 Licensing | 57 Production Licenses | Equinor, Aker BP, Vår Energi |

| Guyana | Field Approval | Hammerhead (7th Project) | ExxonMobil, Hess, CNOOC |

| China | Production Target | 760-780 million BOE | CNOOC, PetroChina |

| Saudi Arabia | Capacity Expansion | 12. 3 million bpd target | Saudi Aramco |

In the Middle East, state-owned giants focused on capacity maximization rather than new exploration frontiers. Saudi Aramco executed its capital plan to raise maximum sustainable capacity to 12. 3 million barrels per day by the end of 2025. This infrastructure build-out contradicts the International Energy Agency’s Net Zero scenario, which requires no new oil fields beyond those approved by 2021. Similarly, the UAE’s ADNOC advanced its gas self-sufficiency strategy, allocating billions to the Hail and Ghasha projects. These investments are not short-term hedges. They are multi-decade capital commitments that necessitate sustained production to generate returns.

China’s offshore giant, CNOOC, set a production target of 760 to 780 million barrels of oil equivalent for 2025, a record high. The company’s strategy involves maintaining flat but elevated capital expenditure, directing 61% of its budget toward development and 16% toward exploration. This distribution confirms that Chinese state planners view domestic oil security as a priority that supersedes immediate decarbonization. The synchronization of these activities across four continents reveals a uniform industry response to climate pledges: acknowledge the in public forums, yet accelerate extraction in the field.

The financial data supports this physical expansion. Rystad Energy reported that while global upstream investment dipped slightly by 2%, deepwater allocations rose by 3%, driven by high-cost, long-pattern projects in Suriname and Mexico. This capital flow into deepwater assets suggests the industry expects demand to remain strong well into the 2030s. The issuance of licenses in 2025 serves as the leading indicator for emissions in 2030. By locking in legal rights to drill today, governments have pre-approved the carbon emissions of the decade.

Renewable Tripling Goal: 2026 Capacity Addition Metrics

The COP28 mandate to triple global renewable energy capacity to 11, 000 gigawatts (GW) by 2030 has bifurcated into two distinct realities: China’s hyper-acceleration and the rest of the world’s stagnation. As of January 1, 2026, the International Energy Agency (IEA) and IRENA confirm that the world is not on a linear trajectory to meet the 11 TW target. While 2025 set a nominal record for capacity additions, the underlying mechanics reveal a dangerous concentration of progress that masks widespread failures in Western markets and the Global South.

In the fiscal year ending December 31, 2025, the global energy sector commissioned approximately 780 GW of new renewable capacity. On the surface, this represents a strong year-over-year increase from the 585 GW added in 2024. yet, a forensic audit of the data indicates that nearly 60% of this expansion occurred within the borders of a single nation: China. The “tripling” goal, designed as a global shared load, has devolved into a unilateral industrial push by Beijing, while the G7 nations shared accounted for less than 15% of the year’s total additions.

The 2025 Capacity Audit

The verified data for 2025 capacity additions exposes the widening chasm between diplomatic pledges and physical infrastructure. China’s National Energy Administration (NEA) reported a 434 GW of combined wind and solar installations in 2025—315 GW of solar PV and 119 GW of wind. This single-year addition exceeds the total installed power generation capacity of Germany and France combined. In contrast, the United States, by the January 2025 revocation of Executive Order 14008 and subsequent policy reversals, saw renewable installations contract by 12% relative to 2024 projections.

| Region/Country | 2025 Solar Added (GW) | 2025 Wind Added (GW) | Total Renewable Added (GW) | Share of Global Growth |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | 315. 0 | 119. 0 | 434. 0 | 55. 6% |

| European Union | 58. 0 | 19. 0 | 77. 0 | 9. 9% |

| United States | 24. 0 | 7. 5 | 31. 5 | 4. 0% |

| India | 28. 0 | 4. 0 | 32. 0 | 4. 1% |

| Rest of World | 145. 0 | 60. 5 | 205. 5 | 26. 4% |

| GLOBAL TOTAL | 570. 0 | 210. 0 | 780. 0 | 100% |

The mathematical reality is that the “Rest of World” category is failing to achieve the necessary growth rates. To meet the 11, 000 GW target by 2030, the world needed to install approximately 1, 100 GW annually starting in 2025. The actual figure of 780 GW leaves a deficit of 320 GW for this year alone. This shortfall compounds the requirement for 2026-2030, pushing the necessary annual addition rate to over 1, 250 GW—a physical impossibility without immediate, command-economy style intervention in Western markets.

The Grid Connection Bottleneck

The primary constraint in 2025 was not capital availability but physical interconnection. IEA data confirms that over 3, 000 GW of renewable projects remain stuck in grid connection queues globally, with the United States and Europe accounting for nearly half of this backlog. In the US, the average wait time for grid interconnection has extended to 5 years. Consequently, investment dollars are flowing into generation assets that cannot be energized. In 2025, curtailment rates in key regions like California and Western China spiked to over 10%, meaning significant portions of zero-carbon electricity were discarded because the transmission infrastructure could not absorb the load.

Furthermore, the “tripling” metric ignores the simultaneous expansion of fossil fuel capacity. While China led the world in renewables, it also commissioned 93 GW of new coal and gas capacity in 2025 to stabilize its grid against the intermittency of its massive solar fleet. This “dual-track” method ensures energy security but negates the decarbonization impact of the renewable additions. The net result is an energy system that is growing larger, not necessarily cleaner, in absolute emissions terms.

2030 Trajectory Assessment

Current projections from the Global Energy Monitor indicate that at the 2025 pace, global renewable capacity can reach approximately 8, 500 GW by 2030—falling 2, 500 GW short of the COP28 pledge. The deficit is almost entirely attributable to the slow pace of deployment in the G7 and the absence of financing for the Global South. Excluding China, the world is on track to only double, not triple, its renewable capacity. The diplomatic victory of Dubai is being dismantled by the logistical and political realities of 2026.

Grid Infrastructure: Interconnection Queues and Transmission Delays

The global energy transition is currently dying in a waiting room. While policymakers celebrate record investment in solar panels and wind turbines, the physical and bureaucratic required to connect these assets to the grid has seized up. Data from 2024 and 2025 reveals that the primary obstacle to decarbonization is no longer the cost of generation, but the impossibility of interconnection. As of late 2025, more renewable capacity is stuck in regulatory limbo than is currently operating worldwide.

In the United States, the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL) confirmed in its Queued Up: 2025 Edition that the backlog of projects seeking grid connection reached approximately 2, 300 gigawatts (GW) by the end of 2024. This figure exceeds the total installed electric generating capacity of the entire country. The queue includes 1, 400 GW of generation and 890 GW of storage. Yet, the completion rate for these projects has plummeted. LBNL data indicates that only 13% of projects entering the queue between 2000 and 2019 reached commercial operation. The median wait time for projects built between 2018 and 2024 has doubled to over four years compared to the early 2000s, pushing 2030 climate into the mid-2030s.

Europe faces an identical paralysis. Reports from late 2025 identify 1, 700 GW of renewable projects stalled in interconnection queues across 16 nations. This backlog is three times the capacity required to meet the EU’s 2030 energy. In the United Kingdom, the queue swelled to over 700 GW before emergency reforms were enacted in 2025 to purge “zombie” projects—speculative applications that reserve grid capacity without financing or land rights. These phantom projects clog the system, forcing viable infrastructure to wait up to 15 years for a connection date.

The Transmission Deficit

The bureaucratic delays mask a more severe physical reality: the world is not building enough wires. The International Energy Agency (IEA) reported in 2025 that while clean energy investment hit $2. 2 trillion, grid investment stagnated at roughly $400 billion per year—half the level required to integrate new generation. This investment gap has resulted in a near-total collapse of new transmission construction in mature markets.

In the United States, the construction of high-voltage transmission lines has ceased. Data from Americans for a Clean Energy Grid shows that in 2024, developers completed only 322 miles of high-voltage transmission lines (rated 345 kV or higher). This represents a catastrophic decline from 2013, when the U. S. built nearly 4, 000 miles of such infrastructure. The Department of Energy estimates the grid must expand by 57% by 2035 to accommodate clean energy mandates, yet the current build rate is less than 10% of the required pace.

The Cost of Congestion

The failure to expand transmission capacity forces grid operators to curtail (discard) cheap renewable energy because it cannot be transported to demand centers. This waste is measurable and rising.

In California, the Independent System Operator (CAISO) curtailed 3. 4 million megawatt-hours (MWh) of wind and solar in 2024, a 29% increase from the previous year. Solar energy accounted for 93% of this wasted power. In Texas, the ERCOT grid curtailed over 8 terawatt-hours (TWh) of wind and solar in 2024, largely due to the inability to move power from the windy western plains to cities in the east. In Europe, the cost of this is: €7. 2 billion worth of clean power was curtailed in just seven countries in 2024 due to grid bottlenecks.

| Region | Queue Backlog (GW) | Transmission Build Rate (2024) | Primary Bottleneck |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States | ~2, 300 GW | 322 miles (High Voltage) | Permitting & Cost Allocation |

| European Union | ~1, 700 GW | Stagnant Cross-Border Links | Grid Congestion & Speculative Queuing |

| United Kingdom | ~722 GW | Reform Phase (Post-2025) | “Zombie” Projects Blocking Capacity |

| China | Data unclear | High (Ultra-High Voltage focus) | Internal Coal vs. Renewable Dispatch |

The data confirms that the energy transition has hit a hard ceiling imposed by infrastructure neglect. Without a massive, immediate acceleration in transmission construction—measured in thousands of miles, not hundreds—the clean energy pipelines celebrated in diplomatic accords can remain theoretical, trapped in spreadsheets rather than powering the grid.

Nuclear Power: Small Modular Reactor Deployment Status

As of December 2025, the global deployment of Small Modular Reactors (SMRs) reveals a clear between diplomatic enthusiasm and physical construction. While the 2020s were marketed as the decade of the SMR “renaissance,” actual grid-connected capacity remains negligible outside of Russia and China. In the West, the sector is characterized by a high volume of regulatory paperwork and a near-total absence of operational hardware.

The Western Stumble: Cancellations and Cost Overruns

The flagship project for the United States nuclear revival, NuScale Power’s Carbon Free Power Project (CFPP) in Idaho, remains terminated as of late 2025. Originally slated to demonstrate the VOYGR reactor design, the project collapsed in November 2023 after updated cost estimates surged to $89 per megawatt-hour (MWh)—a 53% increase from earlier projections. Without the $4 billion in federal subsidies, independent analysis by the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) placed the true cost closer to $120/MWh, rendering it uncompetitive against wind, solar, and natural gas.

This cancellation reverberated through 2024 and 2025, forcing a recalibration of expectations. No commercial SMRs are generating electricity in North America or Europe as of December 31, 2025. The economic reality of “nth-of-a-kind” cost reductions has yet to be tested, as the industry struggles to build the “-of-a-kind” units required to start the learning curve.

Operational Reality: The Eastern Monopoly

While Western nations debate licensing frameworks, China and Russia possess the only commercially operational SMRs in the world.

China: The Shidaowan High-Temperature Gas-Cooled Reactor (HTR-PM) in Shandong province began commercial operation in December 2023 and operated throughout 2024 and 2025. It generates 200 MW using a pebble-bed design that eliminates the risk of a meltdown. In 2025, China National Nuclear Corporation (CNNC) advanced construction on the ACP100 (Linglong One) in Hainan, with grid connection scheduled for 2026.

Russia: The Akademik Lomonosov, a floating nuclear power plant equipped with two KLT-40S reactors, continues to supply heat and power to Pevek in the Arctic. Furthermore, Rosatom is constructing a land-based SMR in Yakutia using the RITM-200N design. Although originally targeted for 2028, commissioning was postponed in January 2025 to 2030 to accommodate a capacity doubling to 110 MW.

2025 Construction Milestones

even with the absence of operational units, 2025 marked the commencement of physical “nuclear construction” for select Western projects, distinguishing them from mere paper proposals.

- Canada: In May 2025, Ontario Power Generation (OPG) received approval to begin construction on the GE Hitachi BWRX-300 at the Darlington site. This unit is the most advanced Western SMR project, with a target completion date of late 2028.

- United States (Tennessee): Kairos Power poured the nuclear safety-related concrete for its Hermes demonstration reactor in Oak Ridge in May 2025. This non-power generating unit is a serious step for licensing molten salt technology.

- United States (Wyoming): TerraPower’s Natrium reactor received a favorable safety evaluation from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) in December 2025. While non-nuclear construction began in 2024, the project faces a 2030 completion timeline, delayed by fuel supply constraints.

The HALEU Supply Chain emergency

A serious bottleneck for non-light water SMRs (like TerraPower and X-energy) is the absence of a domestic supply chain for High-Assay Low-Enriched Uranium (HALEU). As of 2025, Russia’s Tenex remains the only commercial supplier of HALEU globally. The U. S. Department of Energy allocated initial HALEU batches to developers in 2025 from limited stockpiles, but commercial- enrichment facilities in the U. S. (such as Centrus Energy’s Ohio plant) are not expected to meet fleet demand until the early 2030s. This fuel insecurity forces Western developers to design reactors for fuel that does not yet exist in their supply chain.

| Project Name | Location | Technology | Status (Dec 2025) | Est. Grid Connection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shidaowan HTR-PM | China | HTGR (Gas-Cooled) | Operational (Commercial) | Active (2023) |

| Akademik Lomonosov | Russia | PWR (Floating) | Operational (Commercial) | Active (2020) |

| Darlington New Nuclear | Canada | BWRX-300 (Water) | Under Construction | 2028-2029 |

| Hermes Demo | USA (TN) | Molten Salt | Under Construction | 2027 (Non-power) |

| Natrium | USA (WY) | Sodium Fast | Site Prep / Licensing | 2030 |

| CAREM-25 | Argentina | PWR | Stalled (Funding cuts) | Indefinite |

| Carbon Free Power Project | USA (ID) | NuScale VOYGR | Cancelled | N/A |

Financial Viability and Cost Projections

The economic case for SMRs in the 2020-2025 period. The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimated in 2025 that SMR overnight capital costs in the EU hover around $10, 000 per kW, significantly higher than the $6, 600 per kW for traditional large- nuclear. While proponents that factory manufacturing can eventually lower costs, the “learning rate” requires serial production that has not started. Until order books fill sufficiently to justify factory tooling, SMRs remain bespoke construction projects with premium price tags.

The Finance Gap: Auditing the New shared Quantified Goal

The financial architecture of the Paris Agreement has collapsed into a emergency of accounting. In November 2024, at the COP29 summit in Baku, diplomats announced the New shared Quantified Goal (NCQG), the successor to the long-overdue $100 billion target. The final agreement set a floor of $300 billion annually by 2035, a figure that negotiators hailed as a “tripling” of ambition. yet, a forensic audit of the data against the Independent High-Level Expert Group (IHLEG) requirements reveals a catastrophic disconnect. The agreed sum represents less than 13% of the $2. 4 trillion in external finance that emerging markets and developing economies (excluding China) require annually by 2030 to meet climate.

The between the diplomatic pledge and the economic need is not a gap; it is a chasm. While the Baku text includes a broader, non-binding aspiration to mobilize $1. 3 trillion per year from “all public and private sources,” it provides no enforcement method to ensure this capital materializes. The reaction from the Global South was immediate and visceral. The African Group of Negotiators dismissed the $300 billion figure as “a joke,” while India’s delegation labeled the outcome a “betrayal” of the principles of equity. The data supports their fury: the $300 billion target, set for a decade from, fails to account for inflation, meaning its real-world purchasing power in 2035 can likely be lower than the original $100 billion pledge made in 2009.

| Metric | Diplomatic Pledge (NCQG) | Verified Need (IHLEG/UNCTAD) | Deficit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Annual Core Finance Target | $300 Billion (by 2035) | $2. 4 Trillion (by 2030) | -$2. 1 Trillion |

| Adaptation Specifics | Undefined / Aggregated | $400 Billion (Minimum) | Data Unavailable |

| Primary Instrument | Loans & Private Mobilization | Grants & Concessional Finance | Structural Mismatch |

| Contributor Base | Developed Nations (Voluntary for others) | Global North + MDB Reform | Political Deadlock |

The structural integrity of these financial flows is equally compromised. The OECD confirmed that developed nations finally met the original $100 billion goal in 2022, reporting a total of $115. 9 billion. yet, this “achievement” relies on face-value accounting that masks a predatory lending model. Oxfam’s 2024 analysis indicates that the “grant equivalent” value—the actual financial effort minus repayment obligations—was only between $28 billion and $35 billion. Approximately 69% of public climate finance provided in 2022 was in the form of loans, frequently at non-concessional rates. Consequently, climate finance is not reducing the load on the Global South; it is a sovereign debt emergency. For every dollar of climate aid received, developing nations are increasingly forced to cut public services to service external debt, creating a feedback loop of vulnerability.

The “contributor base” debate—the diplomatic fight to force high-emitting emerging economies like China and the Gulf states to pay—ended in a stalemate. The final Baku text encourages these nations to contribute on a voluntary basis, a loophole that preserves the. While China has engaged in South-South cooperation, providing over $4 billion globally, there is no mandatory framework to track or verify these flows comparable to the obligations of traditional donor countries.

“This new finance goal is an insurance policy for humanity… But like any insurance policy – it only works – if premiums are paid in full, and on time.” — Simon Stiell, UN Climate Change Executive Secretary, November 2024.

Current fiscal trends suggest the premiums are not being paid. In 2024, while global clean energy investment surpassed $2 trillion, the vast majority of this capital remained concentrated in advanced economies and China. Conversely, the OECD projects that Official Development Assistance (ODA) budgets faced cuts of 9% to 17% in 2025 due to domestic fiscal tightening in the G7. This retraction occurs simultaneously with a surge in fossil fuel subsidies, which tripled in advanced economies between 2020 and 2022 to shield consumers from energy price spikes. The financial signal is unambiguous: governments are prioritizing short-term fossil fuel stability over the long-term capitalization of the transition.

The “Baku to Belém Roadmap,” intended to the gap to the $1. 3 trillion target by COP30 in 2025, relies heavily on the mobilization of private capital. Yet, the track record of private finance mobilization is poor. For every $1 of public finance, MDBs have historically mobilized less than $1 of private capital in low-income countries. Without a radical restructuring of the World Bank and IMF—specifically regarding Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) and risk guarantees—the $1. 3 trillion figure remains a theoretical construct, disconnected from the liquidity constraints of the real economy.

Loss and Damage: Tracking Fund Disbursements to V20 Nations

The operationalization of the Fund for Responding to Loss and Damage (FRLD) at COP28 was hailed as a diplomatic triumph, yet the financial data for the fiscal year ending December 31, 2025, reveals a method that is functionally insolvent relative to the of destruction. While the diplomatic consensus exists on paper, the banking reality tells a different story: the fund remains a “ghost account,” holding less than 0. 2% of the capital required to address the physical disintegration of the Twenty (V20) nations.

As of November 2025, the total pledged capital to the FRLD stood at approximately $788 million. Of this amount, less than $400 million had been physically transferred to the World Bank-hosted trust. In clear contrast, the V20 Group of Finance Ministers estimated the economic losses for their member states in 2025 alone at $395 billion. This creates a coverage gap of 99. 8%, forcing nations to absorb climate shocks through sovereign debt rather than the promised grants.

The Disbursement Gap: 2025 Fiscal Audit

The following table contrasts the diplomatic pledges made since 2023 with the actual liquidity available for disbursement in late 2025. The data confirms that while the “Global Shield” insurance method triggered small payouts, the core FRLD did not problem a single project grant until the debut call for proposals at COP30 in Belém.

| Metric | Value (USD) | Status |

|---|---|---|

| Total Estimated V20 Damages (2025) | $395, 000, 000, 000 | Verified Loss |

| Total FRLD Pledges | $788, 000, 000 | Committed |

| Actual Funds Transferred to Trust | $398, 000, 000 | Liquid |

| Funds Available for 2025-2026 Projects | $250, 000, 000 | Allocated |

| US Pledge (Withdrawn Nov 2025) | $17, 500, 000 | Defaulted |

| Global Shield Payouts (e. g., Ghana) | ~$3, 000, 000 | Disbursed |

The withdrawal of the United States from the FRLD Board in late 2025, following a pledge of only $17. 5 million, signaled a collapse in confidence from the world’s largest historical emitter. This exit decapitated the fund’s momentum, leaving the European Union and minor contributors to sustain a method that requires billions, not millions. The administrative costs of the fund, managed by the World Bank, consumed approximately $4. 8 million in the half of 2025 alone, further eroding the capital available for disaster victims.

The Sovereign Debt “Doom Loop”

For V20 nations, the absence of functional loss and damage financing has triggered a “debt doom loop.” Without access to grants, countries must borrow to rebuild infrastructure destroyed by climate events they did not cause. In 2025, V20 nations paid $131 billion in external debt service—money that flowed out of economies to creditors in the Global North. This outflow is 331 times larger than the total liquidity sitting in the Loss and Damage Fund.

“We are not receiving aid; we are paying interest on our own destruction. The financial architecture penalizes us for being. Every hurricane is a new loan, and every drought is a credit downgrade.”

The “Global Shield against Climate Risks,” an insurance-based alternative favored by the G7, remains the only active disbursement channel. In 2024 and 2025, it triggered payouts for drought in Ghana totaling roughly $2. 9 million. While these funds provided rapid liquidity, they operate on an insurance model where premiums must be paid, frequently subsidized by aid that could have been used elsewhere. This commodifies disaster response, treating climate reparations as an actuarial product rather than a justice obligation.

2026 Outlook: The Insolvency emergency

The debut call for proposals launched at COP30 offers $250 million for the 2025-2026 period. If distributed equally among the 68 eligible V20 members, each nation would receive approximately $3. 6 million—insufficient to rebuild a single or hospital in most jurisdictions. The data indicates that without a mandatory contribution method based on historical emissions, the Loss and Damage Fund can remain a diplomatic shell, offering performative sympathy while the V20 debt load accelerates toward $1 trillion by 2030.

Private Equity: ESG Fund Allocation vs. Fossil Asset Retention

The financial mechanics of the climate emergency have found a quiet, unregulated harbor in private equity. While public corporations face increasing pressure to decarbonize, a parallel “shadow market” has emerged where fossil fuel assets are not retired, but transferred. Data from the 2025 Private Equity Climate Risks Scorecard confirms that as of January 2025, the energy portfolios of 21 leading private equity firms generated 1. 17 gigatons of CO2 equivalent annually. This figure rivals the total yearly emissions of the global aviation industry and exceeds the carbon output of the 2023 Canadian wildfires.

This transfer of assets constitutes a form of emissions arbitrage. Publicly traded oil and gas majors, seeking to clean their balance sheets for ESG compliance, sell dirty infrastructure to private equity firms that operate outside the scope of public disclosure rules. In 2024, private equity investment in fossil fuel companies rose by 131% year-over-year to $15. 31 billion. During the same period, the sector’s deal value for renewables increased by only 64%. This indicates that private capital is aggressively acquiring the very assets that public markets are attempting to shed.

The Disclosure Gap

The gap between reported emissions and physical reality is clear. KKR, one of the sector’s largest players, reported approximately 14, 000 metric tons of greenhouse gas emissions in its sustainability disclosures. Yet, an April 2024 analysis by the Private Equity Stakeholder Project estimated the actual climate impact of KKR’s portfolio at 64. 3 million tons—roughly 6, 500 times the reported figure. This reporting gap allows firms to market “energy transition” funds while simultaneously extracting value from intensive fossil fuel infrastructure.

The acquisition of Global Infrastructure Partners by BlackRock in late 2024 exemplifies this trend. The deal more than doubled the number of fossil fuel companies in BlackRock’s private portfolio, raising the percentage of its energy assets tied to fossil fuels from 24% to 41%. Across the industry, 65% of energy portfolio companies owned by the top 20 private equity firms remain tied to fossil fuels as of January 2025. At the current rate of divestment, the sector would not exit fossil fuels until 2090.

Capital Expenditure Realities

Bloomberg NEF’s June 2025 report on “Fund-Enabled Capex” provides a mathematical verification of capital priorities. For every $1 of capital expenditure allocated to fossil fuels by global investment funds, only 48 cents flowed to low-carbon assets. This ratio of 0. 48: 1 sits well the 4: 1 ratio required to meet the Paris Agreement. The data rejects the narrative that private equity is a primary driver of the green transition; instead, it functions as a life-support system for aging carbon infrastructure.

| Firm Name | % Energy Portfolio in Fossil Fuels | Est. Annual Emissions (MtCO2e) | 2025 Climate Scorecard Grade |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kayne Anderson | 100% | N/A* | F |

| Quantum Capital Group | >90% | High Intensity | D |

| EIG Global Energy Partners | 82% | 255. 0 | F |

| Carlyle Group | 77% | 214. 0 | D |

| KKR | 64% | 64. 3 | C |

| Apollo Global Management | 60% | 3. 6 | B |

| *Specific emissions data unavailable due to absence of public disclosure. Source: Private Equity Climate Risks Scorecard 2025. | |||

The Human Cost of Privacy

The consequences of this opacity extend beyond atmospheric carbon. A June 2025 report analyzed the localized impact of private equity-backed fossil infrastructure, estimating that these assets cause between $11 billion and $15 billion in annual health damages in the United States alone. These costs manifest in respiratory illnesses and premature deaths in communities surrounding coal plants and LNG terminals—assets that have been “saved” from retirement by private capital injection. The financial returns of these funds are thus directly subsidized by public health deficits.

The structural incentive remains clear. As long as private markets offer a venue for high-emission assets to operate without the scrutiny applied to public companies, the global emissions ledger can remain unbalanced. The 1. 17 gigaton footprint of these 21 firms is not a legacy problem; it is an active, growing liability that undermines the diplomatic progress claimed in public forums.

The operationalization of Article 6—the Paris Agreement’s engine for global carbon trading—was celebrated at COP29 in Baku as a diplomatic triumph. The data for 2025, yet, reveals a method paralyzed by complexity and fraud. While diplomats in Belém (COP30) finalized rulebooks, the physical market for “high-integrity” credits remained statistically insignificant compared to the volume of “junk” offsets flooding the voluntary sector.

The Integrity Deficit: 84% Failure Rate

The fundamental premise of carbon markets—that one tonne of CO2 credited equals one tonne of CO2 removed—collapsed under scrutiny in 2025. A landmark meta-analysis published in Nature Communications (late 2024) and corroborated by 2025 field audits found that 84% of issued credits represented no real emissions reductions.

This “integrity deficit” has rendered the majority of the Voluntary Carbon Market (VCM) useless for genuine climate mitigation. In October 2025, a joint study by the University of Oxford and the University of Pennsylvania concluded that the asset class is ” with intractable problems,” recommending the phasing out of nearly all offsets except those backed by permanent geological storage.

The market response has been a capital flight to quality, but at insufficient volume. While the total value of the market ticked up to $1. 04 billion in 2025 due to higher prices for premium credits, the issuance of new credits dropped to 270 million tonnes—the lowest level since 2020. Buyers are no longer trusting the standard verification bodies, forcing a contraction in liquidity just when the method was meant to.

Article 6. 2: The Bilateral Mirage

Under Article 6. 2, countries can trade “Internationally Transferred Mitigation Outcomes” (ITMOs) to meet their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). In theory, this allows capital to flow to the most decarbonization projects. In practice, it has created a fragmented archipelago of bilateral deals with negligible physical impact.

As of December 2025, even with 108 bilateral agreements being signed, actual verified transfers of ITMOs remain microscopically small. The only fully operationalized transfer chain by early 2025 was the Switzerland-Thailand corridor.

| Metric | Verified Figure | Context |

|---|---|---|

| Signed Bilateral Agreements | 108 | Diplomatic frameworks (e. g., Singapore-Ghana, Japan-JCM). |

| Verified ITMO Transfers | <50, 000 tonnes | Primary volume from Swiss-Thai E-Bus program (1, 916 tonnes initial tranche). |

| Global Emissions (2025) | 38. 1 billion tonnes | ITMOs cover 0. 0001% of global emissions. |

| “Junk” Credit Volume | ~812 million tonnes | Legacy credits with no environmental integrity. |

The Switzerland-Thailand deal, hailed as a “beacon moment,” involved the transfer of just 1, 916 credits in its tranche—a rounding error in global emissions. Meanwhile, Singapore’s aggressive deal-making (contracting 2. 175 million tonnes from Ghana, Peru, and Paraguay) is a future pledge, with delivery scheduled for 2026–2030. The gap between signed MOUs and verified atmospheric reductions is currently over 1, 000 to 1.

The Double Counting Trap and Registry Failure

The central safeguard of Article 6 is the “Corresponding Adjustment” (CA)—an accounting method where the host country deducts sold credits from its own ledger to prevent double counting. Without CAs, both the buyer and seller claim the same emission reduction, rendering the trade environmentally null.

By the end of 2025, the UN had failed to implement a centralized, interoperable registry capable of tracking these adjustments in real-time. Instead, the system relies on a patchwork of national registries that do not speak to one another.

“The Article 6 outcome in Baku creates a system that is so complex and reliant on external officials… it can be difficult to use as a basis for high-integrity actions.” — Carbon Market Watch, November 2024

This absence of infrastructure has allowed “zombie credits” from the defunct Clean Development method (CDM) to re-enter the system. At COP30 in Belem, negotiators extended the transition deadline for CDM projects to June 2026. This decision legalizes the laundering of millions of tonnes of low-quality credits—generated by projects like large hydro and coal efficiency schemes from the 2010s—into the new Paris Agreement framework.

Article 6. 4: A Regulatory Bottleneck

The centralized UN crediting method (Article 6. 4) was meant to replace the CDM with higher standards. While the Supervisory Body finally approved its methodology (for landfill gas) in October 2025, the pipeline is clogged.

Over 1, 000 legacy projects have applied to transition, but only 14 had completed the process by late 2025. The rigorous “downward adjustment” of baselines required by the new rules makes of these projects financially unviable, leading to a standoff between project developers demanding access and a Supervisory Body attempting to maintain minimal integrity.

The result is a market in stasis. The “high-integrity” credits promised by the Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market (ICVCM) are scarce, commanding premiums that few buyers are can to pay, while the cheap, “junk” credits that fueled corporate net-zero claims for a decade are slowly being strangled by regulation, leaving a void that has not been filled.

Green Steel: Production Volumes of Hydrogen-Reduced Iron

The industrial decarbonization narrative for 2025 hinged on the commercial emergence of “green steel”—specifically, iron reduced by hydrogen rather than coal-fired blast furnaces. The data for the fiscal year ending December 31, 2025, reveals a clear between press release capacity and physical output. While global crude steel production held steady at approximately 1. 9 billion tonnes, the volume of commercially traded Hydrogen-Reduced Iron (H2-DRI) remained a statistical rounding error, accounting for less than 0. 2% of the global total. The “green steel revolution” promised by European policymakers has stalled, colliding with the economic reality of hydrogen costs that rendered projects unviable without permanent subsidy.

The most significant indicator of this stagnation occurred on June 20, 2025, when ArcelorMittal, the largest steel producer in Europe, formally halted its flagship decarbonization projects in Bremen and Eisenhüttenstadt, Germany. even with having access to €1. 3 billion in federal subsidies, the company returned the funds, citing the “absence of commercially viable renewable hydrogen” and uncompetitive energy economics. This cancellation marked a turning point; it was not a delay in permitting, but a rejection of the fundamental business case for hydrogen-based steelmaking in the current energy market. Similarly, Thyssenkrupp Steel suspended its tender for green hydrogen in March 2025, admitting that bidder prices were “significantly higher” than the threshold required for solvent operation.

In Sweden, frequently as the vanguard of this technology, progress remains confined to construction sites and pilot facilities rather than commercial shipping lanes. Stegra (formerly H2 Green Steel) continued construction on its Boden facility throughout 2025, but the plant did not produce commercial volumes during the audit period, with the start of operations pushed to 2026. The HYBRIT consortium (SSAB, LKAB, Vattenfall) successfully demonstrated large- hydrogen storage in 2025 but remained in the pilot phase, producing only minute quantities of fossil-free steel for promotional partnerships with automotive manufacturers like Volvo. The promised flood of zero-carbon steel into the European market did not materialize.

Paradoxically, the only operational facilities method commercial in 2025 were located in China, the world’s largest carbon emitter. The HBIS Group’s plant in Zhangjiakou, Hebei Province, operated a 1. 2 million-tonne hydrogen metallurgy demonstration project. In late 2024 and throughout 2025, HBIS integrated this output into a new continuous casting line for automotive sheets. yet, verification audits suggest that even this facility relies on “hydrogen-enriched” gases derived from coke ovens or coal gasification rather than 100% electrolytic green hydrogen, meaning the carbon intensity is lower than a blast furnace but far from zero.

| Project / Company | Location | 2025 Target Status | Actual 2025 Status | Verified Output (Mt) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ArcelorMittal (DrI/EAF) | Germany | Construction Start | Project Cancelled (June 2025) | 0. 0 |

| Thyssenkrupp (tkH2Steel) | Germany | Hydrogen Procurement | Tender Suspended (March 2025) | 0. 0 |

| Stegra (H2 Green Steel) | Sweden | Initial Production | Construction Ongoing | 0. 0 |

| HBIS Group (Zhangjiakou) | China | Commercial Ops | Operational (Demo ) | ~0. 8 – 1. 2* |

| HYBRIT Pilot | Sweden | Pilot Operations | Operational (Pilot Only) | <0. 05 |

| *Output estimate based on nameplate capacity; fuel source contains grey hydrogen mix. | ||||

The failure to launch in 2025 from the “Green Premium”—the cost difference between hydrogen-reduced iron and conventional coal-based pig iron. In 2025, green hydrogen traded at prices three to four times higher than the thermal equivalent of metallurgical coal. Without a global carbon price exceeding $150 per tonne, the economics of H2-DRI remain inverted. Consequently, the global steel industry’s emissions intensity did not drop in 2025; instead, producers optimized existing blast furnaces or expanded gas-based Direct Reduced Iron (DRI) capacity, which reduces emissions by only 40-50% compared to coal, locking in fossil fuel dependency for another investment pattern.

EV Saturation: Sales Penetration Rates in Emerging Markets

While Western markets grappled with demand plateaus and policy reversals in 2025, the Global South emerged as the primary engine of electric vehicle (EV) expansion. Verified sales data for the fiscal year ending December 31, 2025, indicates a decoupling of global trends: as European and North American adoption curves flattened, emerging markets in Asia and Latin America experienced exponential saturation, driven not by environmental ideology but by aggressive price parity and Chinese export dominance.

China, the global epicenter of this shift, officially breached the “tipping point” in 2025. Data from the China Passenger Car Association (CPCA) confirms that New Energy Vehicles (NEVs) accounted for 51% of all new car sales year-to-date by August 2025, relegating the internal combustion engine to minority status in the world’s largest auto market. This saturation was fueled by a price war that saw battery-electric models undercut gasoline equivalents, a yet to materialize in the West.

The Southeast Asian Surge

The most rapid acceleration occurred in Southeast Asia, where Chinese OEMs (Original Equipment Manufacturers) utilized the region as a primary export valve. Thailand, traditionally a Japanese automotive stronghold, saw EV penetration surge to 18% by November 2025, up from 11% in 2024. This growth, yet, revealed acute infrastructure disparities; registration data shows the Bangkok Metropolitan Region absorbed 69% of all Thai EV sales, creating a localized saturation emergency while provincial adoption lagged due to charging deserts.

Vietnam presented a unique case of vertical integration. Domestic manufacturer VinFast delivered a record 175, 099 units in 2025, doubling its 2024 performance. This single-brand dominance pushed Vietnam’s EV market share to approximately 30%, surpassing European nations. Conversely, Indonesia’s market, leveraging its nickel reserves, saw penetration jump from 5% in 2024 to nearly 18% in 2025, with sales volume surpassing 55, 000 units by Q3.

Latin America: The Hybrid

Brazil and Mexico diverged from the Asian “BEV-” (Battery Electric Vehicle) model, favoring flexible fuel solutions. In Brazil, the market grew by 42. 1% in 2025, reaching a 5% total market share. yet, the composition of this fleet is distinct: Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicles (PHEVs) accounted for two-thirds of sales, driven by models like the BYD Song which offer ethanol compatibility. Mexico, serving as a manufacturing hub for the North American market, recorded domestic sales of 96, 636 electrified units, achieving a penetration rate of roughly 9. 5%.

| Market | 2024 Penetration (%) | 2025 Penetration (%) | Primary Driver |

|---|---|---|---|

| China | 36. 0% | 51. 0% | Price Parity / BEV Dominance |

| Vietnam | 16. 0% | 30. 0% | VinFast Domestic Supply |

| Thailand | 11. 4% | 18. 0% | Chinese Imports (BYD/MG) |

| Indonesia | 5. 0% | 18. 0% | Fiscal Incentives / Nickel Policy |

| India (4W) | 2. 5% | 4. 3% | Fleet Adoption / Tata Motors |

| India (3W) | 20. 8% | 31. 8% | Cost of Operations / Last Mile |

| Brazil | 3. 5% | 5. 4% | PHEV Preference |

India: The Two-Wheeled Revolution

India’s electrification story remains distinct from the global passenger car narrative. While 4-wheeler penetration rose modestly to 4. 3% (196, 724 units), the true saturation occurred in the micro-mobility sector. Electric 3-wheelers, the backbone of urban transit, reached a penetration rate of 31. 8% in 2025, up from 20. 8% the previous year. Two-wheelers accounted for 56% of all EV sales in the country, with 1. 28 million units sold. This data confirms that for the world’s most populous nation, the “EV transition” is primarily a fleet and logistics phenomenon rather than a private ownership trend.

“The data from 2025 proves that the ‘Global South’ is no longer a laggard but a leader in specific EV segments. yet, the between vehicle sales and charging infrastructure in cities like Bangkok and Mumbai suggests we are hitting a ‘hard ceiling’ of physical saturation, where grid stability, not consumer demand, becomes the limiting factor.”

The in 2025 is clear: while the West debates tariffs and range anxiety, emerging markets are absorbing capacity at rates that earlier International Energy Agency (IEA) projections. The saturation of Chinese exports into these regions has lowered the entry barrier, making 2025 the year the “electric premium” evaporated for billions of consumers.

Aviation Fuels: Sustainable Aviation Fuel Supply Chain Audit

The aviation sector’s decarbonization strategy, heavily reliant on the rapid scaling of Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF), collided with physical and economic realities in 2025. even with a decade of press releases promising a “green revolution” in flight, verified production data for the fiscal year ending December 31, 2025, reveals a market paralyzed by feedstock scarcity, prohibitive costs, and supply chain fraud. The International Air Transport Association (IATA) confirmed that global SAF production reached approximately 2. 1 million tonnes in 2025. While this represents a doubling of 2024 volumes, it accounts for a statistically negligible 0. 7% of global jet fuel consumption. The industry remains 99. 3% dependent on fossil kerosene, rendering the “net-zero by 2050” flight route mathematically impossible under current trajectories.

The between diplomatic ambition and industrial capacity is most visible in the United States. The “SAF Grand Challenge,” launched by the Biden-Harris administration with a target of producing 3 billion gallons annually by 2030, is failing to meet the necessary growth rates. Federal data indicates that domestic production through the third quarter of 2024 totaled only 93 million gallons. Even with optimistic projections for late 2025, the U. S. is producing less than 5% of the volume required to stay on track for its 2030 goal. The gap is not logistical but structural; the capital expenditure required to build the necessary biorefineries has not materialized at the pace required to displace conventional refining infrastructure.

The Feedstock Fraud emergency

The integrity of the SAF supply chain faced a severe credibility emergency in 2025 regarding its primary feedstock: Used Cooking Oil (UCO). Hydroprocessed Esters and Fatty Acids (HEFA), the technology responsible for over 80% of current SAF production, relies heavily on waste oils. yet, demand has outstripped the genuine supply of waste grease from restaurants and industrial kitchens.

Investigations by European and American regulatory bodies in 2024 and 2025 uncovered widespread “laundering” of virgin palm oil. Traders in Asia were found to be exporting fresh palm oil—linked to deforestation—relabeling it as “waste oil” to bypass sustainability criteria and capture premium subsidies in the EU and US markets. In Europe, which imports 80% of its UCO, primarily from China, the volume of “used” oil entering the bloc exceeded the theoretical collection capacity of the exporting regions. This fraudulent arbitrage undermines the carbon reduction claims of the fuel; burning virgin palm oil in jet engines can result in higher lifecycle emissions than conventional fossil jet fuel due to land-use change.

The Cost Barrier

The economic audit of 2025 proves that SAF remains a luxury good rather than a commodity fuel. As of January 2026, the price differential between SAF and conventional Jet A-1 fuel remains prohibitive for an industry operating on thin margins.

| Fuel Type | Price per Metric Ton (USD) | Price Premium vs. Fossil Jet |

|---|---|---|

| Conventional Jet A-1 | $741 | — |

| HEFA-SAF (Bio-based) | $2, 286 | +208% |

| e-SAF (Synthetic/Power-to-Liquid) | ~$7, 695 | +938% |

This price gap imposed an additional $3. 6 billion in fuel costs on the airline industry in 2025 alone. With the European Union’s ReFuelEU Aviation mandate forcing a 2% blend rate starting January 1, 2025, European carriers were forced to absorb these costs or pass them to passengers. Consequently, ticket prices on routes subject to mandates saw surcharges rise, yet the environmental benefit was diluted by the feedstock provenance problem above.

The Synthetic Fuel Mirage

Perhaps the most serious failure in the 2025 audit is the absence of “Power-to-Liquid” (PtL) or e-fuels. These synthetic fuels, made from green hydrogen and captured carbon dioxide, are theoretically beyond the limits of biomass. yet, as of late 2025, commercial production of e-SAF was virtually non-existent. The European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) reported that no synthetic SAF projects had reached a Final Investment Decision (FID) by the start of the mandate period. The projected cost of over $7, 600 per tonne makes e-SAF economically unviable without massive, sustained public subsidies that governments have been hesitant to guarantee.

“The capacity is limited and the number of sellers is limited… even modest changes in supply or demand can create pronounced imbalances.” — International Air Transport Association (IATA) Statement, December 2025.

The 2025 data confirms that the aviation sector is not transitioning; it is. The reliance on a finite, fraud- supply of waste oil has created a bottleneck that HEFA technology cannot solve. Without a breakthrough in e-fuel economics or a massive diversion of agricultural land to fuel production—a move that would trigger food security crises—the aviation industry’s emissions can continue to track with passenger demand, which remains strong upward.

Maritime Shipping: Methanol and Ammonia Vessel Order Books

The maritime sector’s transition to alternative fuels hit a mathematical wall in 2025. While press releases from major carriers touted a “green revolution,” the verified order book data from DNV’s Alternative Fuels Insight (AFI) platform reveals a sharp contraction in momentum. After a surge in 2024, orders for methanol-capable vessels plummeted by approximately 53% in 2025, dropping to just 61 vessels compared to 149 the previous year. This retraction exposes the industry’s collision with the “supply gap”—the physical absence of green fuel to power these ships.