Forged Masters: The European Gallery Scandal

On March 1, 2016, the quiet reverence of the Caumont Centre d’Art in Aix-en-Provence was shattered by the arrival of the Central Office for the Fight Against Cultural Goods Trafficking (OCBC). Their target was not a thief, but a painting: Venus with a Veil, a small oil on oak panel attributed to the German Renaissance master Lucas Cranach the Elder. The work, dated 1531, served as the star attraction and catalogue cover for the exhibition “The Collections of the Prince of Liechtenstein.”

Investigators acted on a warrant issued by Parisian Judge Aude Buresi. They removed the panel from the gallery walls in front of stunned staff, marking the public explosion of a European Gallery Scandal that had festered in the shadows of the European art market since 2014. The seizure was a direct challenge to the Princely Collections of Liechtenstein, which had purchased the work in 2013 for €7 million ($9. 7 million at the time) from the prestigious Colnaghi gallery in London. The raid signaled that French authorities possessed credible evidence—later revealed as a tip-off regarding modern pigments—that this “masterpiece” was a modern forgery.

The confiscation triggered a diplomatic and legal firestorm. The Prince of Liechtenstein, Hans-Adam II, owner of one of the world’s most significant private art collections, found his judgment and his acquisitions team publicly questioned. The OCBC did not act on a whim; they carried suspicions that the Venus was part of a massive inventory of fakes linked to Giuliano Ruffini, a French collector living in Italy. This event forced the art world to confront a terrifying possibility: that a single workshop had successfully infiltrated the highest echelons of the market, fooling Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The 20-Point Dossier: Key Facts of the Scandal

To understand the scope of this investigation, we present the core data points established by French and Italian authorities between 2015 and 2025.

| Question | Fact / Answer |

|---|---|

| 1. What was seized? | Venus with a Veil, attributed to Lucas Cranach the Elder (dated 1531). |

| 2. When was the raid? | March 1, 2016. |

| 3. Where did it occur? | Caumont Centre d’Art, Aix-en-Provence, France. |

| 4. Who ordered the seizure? | Judge Aude Buresi, Paris Tribunal. |

| 5. Who owned the painting? | Hans-Adam II, Prince of Liechtenstein. |

| 6. What was the purchase price? | €7 million (approx. $9. 7 million in 2013). |

| 7. Who sold the work? | Colnaghi Gallery, London (sourced from Giuliano Ruffini). |

| 8. Who is the suspected mastermind? | Giuliano Ruffini, a French collector based in Reggio Emilia. |

| 9. Who is the suspected forger? | Lino Frongia, an Italian painter (acquitted/charges dismissed in jurisdictions). |

| 10. What triggered the investigation? | An anonymous letter sent to French police in 2014. |

| 11. What scientific proof exists? | Titanium white (modern pigment) and plastic-coated fibers found in the paint. |

| 12. How was the panel aged? | Thermal analysis suggests the wood was baked to induce cracks. |

| 13. Was the painting returned? | Yes, in 2021, after the Prince was deemed an “owner of good faith.” |

| 14. Is it authentic? | French courts ruled it a forgery based on the 213-page expert report. |

| 15. How fakes are suspected? | Authorities estimate between 25 and 50 works. |

| 16. What is the total fraud value? | Estimated over €200 million. |

| 17. Who else bought these works? | Sotheby’s (Frans Hals), The Metropolitan Museum of Art, private collectors. |

| 18. What is Ruffini’s defense? | He claims he never attributed the works, leaving authentication to experts. |

| 19. What police unit led the raid? | OCBC (Central Office for the Fight Against Cultural Goods Trafficking). |

| 20. What is the current status? | Civil and criminal litigations continue in France and Italy as of 2025. |

The Mechanics of the Deception

The seizure at Caumont was the culmination of a two-year covert inquiry. The Venus had entered the market with a provenance that appeared impeccable on the surface yet disintegrated under scrutiny. Ruffini claimed the work came from the collection of André Borie, a civil engineer, yet no concrete records placed the painting in Borie’s possession during his lifetime. The painting bypassed standard scrutiny because recognized experts, including those at the Louvre, had initially expressed interest or validated its quality.

Judge Buresi commissioned a detailed scientific analysis from the Center for Research and Restoration of the Museums of France (C2RMF). The results, finalized in a 213-page report, were damning. The presence of titanium white in the pearl necklace—a pigment not available until the 1920s—proved the work could not have been painted in 1531. Furthermore, the “craquelure” (the network of fine cracks that usually indicates age) was inconsistent with natural drying processes. The report concluded the panel had been subjected to rapid thermal cycling, baking the wood to simulate centuries of wear.

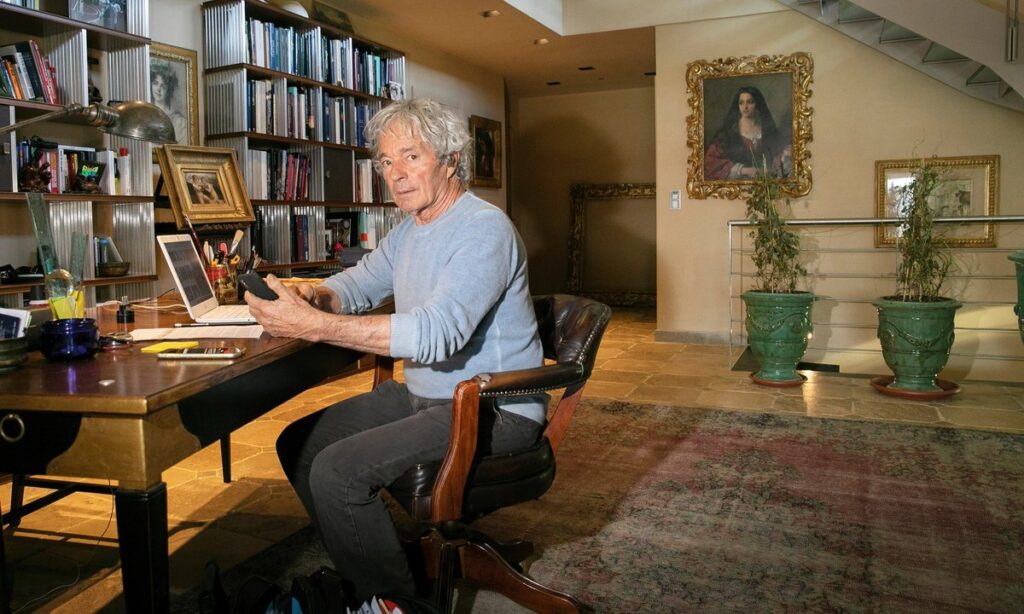

Article image: Forged Masters: The European Gallery Scandal

The Prince of Liechtenstein’s collection fought the seizure, arguing that the painting was genuine and that the seizure violated property rights. In 2021, the Paris Court of Appeal ordered the return of the painting to the Prince. The court did not validate the painting’s authenticity—in fact, it acknowledged the strong evidence of forgery—but ruled that the Prince, having bought the work in good faith, should not be permanently deprived of his property. The Venus returned to the Liechtenstein vaults, no longer a masterpiece, but a €7 million piece of evidence in one of history’s most sophisticated art crimes.

The Ruffini Network: Mapping the hierarchy of a suspected forgery ring

The seizure of the Cranach Venus was not an incident but the tug on a thread that unraveled a sophisticated, multi- criminal enterprise. Investigators led by Judge Aude Buresi have mapped a hierarchy that extends far beyond Giuliano Ruffini, the charismatic French collector at the center of the scandal. The network, described by prosecutors as a “gang fraud” operation, allegedly generated up to €200 million through the sale of Old Master forgeries, relying on a strict division of labor between the creator, the face, and the financiers.

At the creative heart of this network stands Lino Frongia, a Parmesan painter known for his skill in “magical realism” and Neo-Mannerist styles. Italian authorities arrested Frongia on June 26, 2023, in Montecchio, executing a European Arrest Warrant issued by the Paris Judicial Tribunal. While Frongia has publicly denied involvement, French investigators identify him as the “hand” behind the canvases. His technical proficiency allowed him to mimic the brushwork of diverse masters, from the German Renaissance style of Lucas Cranach to the loose, expressive strokes of Frans Hals. In 2019, Frongia was briefly detained after a San Francesco attributed to El Greco was seized from an exhibition in Treviso, but a Bologna court initially refused his extradition. The 2023 arrest marked a serious turning point, with charges of fraud and money laundering on the artist nicknamed the “Moriarty of forgers” by the British press.

Giuliano Ruffini operated as the “face” of the enterprise, carefully cultivating a persona of the “lucky amateur.” Rather than claiming expertise, Ruffini presented himself as a collector who stumbled upon unrecognized treasures, leaving the dangerous work of attribution to eager experts and market-hungry dealers. To explain the sudden appearance of so masterpieces, Ruffini relied on a “ghost” provenance: the collection of Andrée Borie. Borie, a gallery owner and Ruffini’s former partner who died in 1980, became the convenient, unverifiable source for dozens of works. By claiming these paintings had sat in her private collection for decades, Ruffini bypassed the scrutiny usually applied to fresh market discoveries.

Article image: Forged Masters: The European Gallery Scandal

The financial and logistical infrastructure was allegedly managed by Mathieu Ruffini, Giuliano’s son, and Jean-Charles Méthiaz. Mathieu Ruffini is charged with money laundering, with investigators tracing a €740, 000 wire transfer from his accounts to Lino Frongia—a payment prosecutors is compensation for the forgeries. Méthiaz, operating through a Delaware-registered shell company called “The Art Factory,” served as a crucial buffer. He consigned the Cranach Venus to Christie’s and later facilitated its sale to the Prince of Liechtenstein, distancing Giuliano Ruffini from the direct transaction and adding a of corporate legitimacy to the sales.

Physical evidence seized during raids in Reggio Emilia provided a glimpse into the network’s technical methods. In the basement of Ruffini’s home, police discovered a large industrial oven. While Ruffini claimed it was used for cooking salmon for large dinner parties, forensic experts suspect it served a more nefarious purpose: baking fresh oil paintings to induce premature cracking (craquelure), a hallmark of age that frequently fools initial visual inspections. This “baking” technique, combined with the use of period-correct wood panels frequently sourced from cheap antique furniture, allowed the forgeries to pass basic dating tests.

Key Figures in the Ruffini Investigation

| Name | Role | Status (as of 2024) | Alleged Activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Giuliano Ruffini | The Face / Distributor | Extradited to France (Dec 2022), under house arrest | Marketed paintings as “unattributed” finds; used Borie provenance. |

| Lino Frongia | The Artist (Suspected) | Arrested in Italy (June 2023) on European Warrant | Creation of fakes mimicking Hals, Cranach, Gentileschi, El Greco. |

| Mathieu Ruffini | The Financier | Charged with money laundering | Managed financial flows; transferred €740k to Frongia. |

| Jean-Charles Méthiaz | The Intermediary | Under investigation | Used “The Art Factory” (Delaware) to consign works to auction houses. |

Alchemy of Deception: Baking canvases and sourcing period pigments

The seizure of the Cranach Venus was not a legal intervention; it was the breach of a high-tech illusion. While the art market relied on the connoisseur’s eye—a subjective tool to psychological manipulation—the forgers relied on a sophisticated “kitchen” designed to defeat the objective tools of science. At the center of this alchemy was a blend of authentic period materials and accelerated aging techniques so precise they initially blinded the world’s leading experts.

The primary weapon in this deception was the manipulation of time itself. An anonymous letter sent to French authorities in 2014 alleged that Giuliano Ruffini, the dealer at the heart of the scandal, utilized a “well-hidden oven” at his home in Codena, Italy, to bake fresh oil paintings. This thermal shock was intended to induce craquelure—the network of fine cracks that naturally forms over centuries as paint dry and contract. Scientific analysis of the seized Venus with a Veil later corroborated this theory. A 213-page report commissioned by the French courts found a cracking network consistent with “artificial ageing,” suggesting the panel had been subjected to rapid heating to simulate 500 years of wear in a matter of hours.

To defeat carbon dating and dendrochronology (tree-ring dating), the forgers employed a method known as “palimpsest.” They sourced genuine, low-value paintings from the 16th and 17th centuries—frequently depicting minor religious scenes or portraits by unknown followers—and scraped the surfaces down to the original wood or canvas. This provided a scientifically perfect support. When experts dated the oak panel of the Venus or the wood of the St. Jerome, the results were indisputably from the correct era. The wood was real; only the image upon it was a lie.

| Work Attributed To | Sale Price / Value | Scientific “Smoking Gun” | Laboratory |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frans Hals | $11. 75 Million | Synthetic 20th-century materials in ground | Orion Analytical |

| Lucas Cranach the Elder | €7. 0 Million | Artificial thermal aging (baking); Titanium White | C2RMF (French Museums) |

| Parmigianino (Circle of) | $842, 500 | Phthalocyanine Green (invented 1936) | Orion Analytical |

The undoing of this technical wizardry came down to molecular hubris. In 2016, Sotheby’s acquired Orion Analytical, a materials analysis firm led by James Martin, to investigate the St. Jerome attributed to the circle of Parmigianino. Martin took 21 samples from the painting. Every single sample contained Phthalocyanine Green, a synthetic pigment not invented until 1936, four centuries after the artist’s death. The forgers had successfully sourced period-appropriate lead-tin yellow and lapis lazuli for other works, but this single anachronism in the green mixture shattered the illusion. Similarly, the Venus was found to contain Titanium White, a pigment that did not exist before 1921, buried deep within its paint.

The hand behind these creations is believed to be Lino Frongia, a northern Italian painter arrested in 2019 and again in 2023. Unlike the infamous forger Han van Meegeren, who created clumsy pastiches, Frongia was a skilled Mannerist capable of channeling the “soul” of the Old Masters. His technique involved a “magical realist” application of paint that appealed to modern tastes while mimicking ancient brushwork. He did not copy existing famous works; he created “missing” masterpieces that the market was desperate to find. This psychological insight, combined with the technical rigor of baking and period supports, allowed the ring to bypass the initial skepticism of the world’s most prestigious institutions.

Paper Trails: Fabricating provenance documents for nonexistent histories

The genius of the forgery ring lay not just in the chemistry of the paint, but in the architecture of the lie. While the physical artworks were executed with forensic precision, their entry into the legitimate market required a credible history—a provenance that could explain why masterpieces by Lucas Cranach the Elder, Frans Hals, and Parmigianino had remained invisible to scholars for centuries. The solution was the invention of a “ghost” collection, anchored by a single, unassuming document that became the of a multimillion-euro fraud.

At the center of this fabrication was the name André Borie. Giuliano Ruffini, the French collector at the heart of the scandal, consistently claimed that the works he brought to market originated from Borie, a civil engineer and recipient of the Legion of Honour who had helped construct the Mont Blanc tunnel. According to Ruffini, Borie was the father of his former partner, Andrée Borie, and had bequeathed a trove of Old Masters to him. This backstory provided the perfect cover: a wealthy, private individual who collected discreetly, explaining the total absence of the paintings in prior auction catalogues or academic literature.

The primary physical evidence supporting this narrative was a handwritten list dated 1973. This document, ostensibly a record of the transfer of ownership, listed six specific paintings ceded to Ruffini. For investigators, this piece of paper was the “Rosetta Stone” of the fraud. It served a dual purpose: it established a legal claim of ownership for Ruffini while simultaneously backdating the history of the works to a pre-internet era, making verification nearly impossible for eager buyers. By anchoring the paintings to a dead man in the 1970s, the forgers erased the need for 16th or 17th-century documentation, replacing centuries of silence with a single, plausible link.

The “Borie provenance” acted as a laundering method. Once a painting was accepted as part of this hidden collection, the absence of earlier records was no longer a red flag but a selling point—a “fresh to market” discovery that dealers and auction houses crave. The Venus with a Veil, attributed to Cranach and sold to the Prince of Liechtenstein for €7 million, relied heavily on this manufactured obscurity. The painting’s sudden appearance was not treated with suspicion but with excitement, as experts rushed to authenticate a “lost” treasure rather than investigate its bureaucratic history.

In cases, the paper trail was by the complicity—unwitting or otherwise—of intermediaries. When the Saint Jerome attributed to the circle of Parmigianino was sold at Sotheby’s New York in 2012 for $842, 500, it carried the weight of expert attributions that had been secured based on the painting’s visual quality, which then retroactively validated the thin provenance. The forgers understood that in the high- world of Old Masters, a beautiful painting frequently blinds experts to a shallow history. The documents did not need to be extensive; they just needed to be sufficient to allow greed to suspend disbelief.

Works Linked to the “André Borie” Provenance

| Attributed Artist | Artwork Title | Sale/Valuation | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lucas Cranach the Elder | Venus with a Veil | Sold for €7, 000, 000 (2013) | Seized by French authorities; declared a modern forgery. |

| Frans Hals | Portrait of a Man | Sold for $11, 750, 000 (2011) | Sale rescinded by Sotheby’s; pigments found to be modern. |

| Orazio Gentileschi | David Contemplating the Head of Goliath | Valued at approx. €25, 000, 000 | Seized in London; subject of ongoing litigation. |

| Parmigianino (Circle of) | Saint Jerome | Sold for $842, 500 (2012) | Sale rescinded; synthetic phthalocyanine green pigment detected. |

| Bronzino | Portrait of a Man | Offered for €3, 000, 000 | Seized by French investigators. |

The investigation revealed that the 1973 list was likely a retroactive fabrication, created to fit the inventory of forgeries as they were produced. By 2019, French magistrates had issued arrest warrants based on the belief that this “paper trail” was nothing more than a smokescreen designed to the sale of freshly painted works. The reliance on a single, unverifiable source—the estate of a deceased engineer—exposed a widespread vulnerability in the art market, where provenance research is frequently treated as a formality rather than a forensic need.

The $10 Million Refund: Sotheby’s and the Fake Frans Hals

The seizure of the Cranach Venus in France sent a shockwave through the executive offices of Sotheby’s in New York. If the Venus—sourced from the obscure French collector Giuliano Ruffini—was a forgery, then every work associated with him was radioactive. For Sotheby’s, the immediate danger was a portrait attributed to the Dutch Golden Age master Frans Hals, titled Portrait of a Man. The auction house had brokered the private sale of this work in 2011 for $10. 75 million to Seattle property developer Richard Hedreen. With the integrity of the Old Master market crumbling, Sotheby’s could not afford to wait for a court order. They needed scientific certainty, and they needed it immediately.

In 2016, Sotheby’s retained James Martin, the founder of Orion Analytical, a materials analysis firm based in Williamstown, Massachusetts. Martin, a forensic specialist who had previously exposed the Knoedler Gallery fakes, was tasked with subjecting the Hals to rigorous testing. The were absolute: if the painting was genuine, Sotheby’s would save face; if it was a fake, they faced an eight-figure liability and a reputational catastrophe.

The Forensic Smoking Gun

Martin’s analysis dismantled the attribution to Frans Hals with clinical precision. The painting, which had been authenticated by leading art historians and even declared a “national treasure” by the French government in 2008, contained materials that did not exist in the 17th century. Martin identified the presence of phthalocyanine blue, a synthetic pigment manufactured in the 1930s, and titanium white, which was not available to artists until the 1920s. These pigments were not surface retouches; they were deep within the foundational paint, proving the work was a modern creation intended to deceive.

Article image: Forged Masters: The European Gallery Scandal

Faced with irrefutable scientific evidence, Sotheby’s acted unilaterally. In 2016, the auction house rescinded the sale and refunded EPC Nevada LLC, Hedreen’s company, the full purchase price of $10. 75 million. This decision, while protecting their client, left Sotheby’s with a $10 million hole in their ledger and a forged painting in their possession. The auction house then turned its legal artillery on the sellers: London dealer Mark Weiss and the investment firm Fairlight Art Ventures.

The Legal Battle for Restitution

The subsequent legal war exposed the unclear financial of the high-end art trade. Sotheby’s sued Mark Weiss Ltd. and Fairlight Art Ventures to recover the refunded millions. The sellers had originally purchased the painting from Ruffini in 2010 for €3 million, marking up the price by over 250% for the sale to Hedreen just a year later. Weiss and Fairlight fiercely contested the forgery allegations, relying on the “connoisseurship” defense—that the eye of the expert outweighed the data of the scientist.

yet, as the 2019 trial method, the defense fractured. Mark Weiss settled with Sotheby’s hours before court proceedings began, agreeing to pay $4. 2 million without admitting liability. Fairlight Art Ventures, led by hedge fund manager David Kowitz, refused to settle, arguing they were “financiers” of the deal and not contractually liable to Sotheby’s. The High Court in London disagreed. In December 2019, Justice Robin Knowles ruled in favor of Sotheby’s, ordering Fairlight to pay approximately $5. 3 million plus interest and costs. The court’s decision reinforced a new reality in the art market: scientific testing had usurped the traditional authority of the connoisseur.

Financial Anatomy of the Scandal

The flow of money in the Frans Hals transaction illustrates the immense profit margins that drive the trade in unproven Old Masters. The table details the escalation of value from the source to the final buyer.

| Transaction Stage | Date | Amount (USD approx.) | Parties Involved |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Purchase | 2010 | $3, 400, 000 (€3m) | Giuliano Ruffini to Mark Weiss & Fairlight Art Ventures |

| Private Treaty Sale | 2011 | $10, 750, 000 | Weiss/Fairlight to Richard Hedreen (via Sotheby’s) |

| Gross Profit | 2011 | $7, 350, 000 | Split between Weiss and Fairlight |

| Refund | 2016 | $10, 750, 000 | Sotheby’s to Richard Hedreen |

| Settlement | 2019 | $4, 200, 000 | Mark Weiss to Sotheby’s |

| Court Judgment | 2019 | $5, 300, 000+ | Fairlight Art Ventures to Sotheby’s |

The ruling against Fairlight was upheld by the Court of Appeal in November 2020, cementing the liability of art investors who partner with dealers. The case also prompted Sotheby’s to acquire Orion Analytical later in 2016, bringing James Martin in-house as the Director of Scientific Research. This move signaled a permanent shift in the industry: the era of authentication by “eye” alone was over.

Scientific Forensics: How Orion Analytical exposed the modern blue

The seizure of the Cranach Venus in March 2016 triggered a panic that rippled from Aix-en-Provence to New York, but it was the forensic analysis of a different painting that provided the irrefutable proof of a modern forgery ring. Following the raid, Sotheby’s, which had sold a portrait attributed to Frans Hals for $11. 2 million in 2011, voluntarily submitted the work to Orion Analytical, a materials analysis firm in Williamstown, Massachusetts. The firm’s founder, James Martin, was tasked with a specific objective: to determine if the Portrait of a Man was a 17th-century masterpiece or a 21st-century fabrication.

Martin’s examination utilized Raman spectroscopy, a technique that uses laser light to identify the molecular fingerprint of pigments. The results were devastating for the Old Master market. Buried deep within the painting’s ground —the preparatory surface applied directly to the canvas before the artist begins—Martin detected Phthalocyanine Blue. This synthetic pigment, known chemically as PB15, was not invented until 1935, three centuries after Frans Hals died in 1666. Its presence in the foundational meant the work could not be a restored original; it was a total forgery created on a modern timeline.

| Painting Attributed To | Pigment Identified | Pigment Invention Date | Artist Death Date | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frans Hals | Phthalocyanine Blue (PB15) | 1935 | 1666 | Modern Forgery |

| Parmigianino (Circle of) | Phthalocyanine Green (PG7) | 1938 | 1540 | Modern Forgery |

| Lucas Cranach the Elder | Titanium White (Rutile) | 1916 | 1553 | Modern Forgery |

The discovery of Phthalocyanine Blue was the “smoking gun” investigators needed. Unlike lead-tin yellow or azurite, which were standard in the 1600s, this modern blue is a hallmark of 20th-century industrial chemistry. Martin’s report detailed that the pigment was not a surface accretion from a later restoration but was integral to the painting’s structure. In the case of the Saint Jerome attributed to the circle of Parmigianino, Martin found Phthalocyanine Green in more than twenty distinct locations across the panel, confirming a systematic use of modern materials by the forger.

The of these findings extended beyond a single sale. The presence of identical modern contaminants across multiple works linked to the same source—Giuliano Ruffini—suggested a single, highly skilled operation rather than fakes. The forger had gone to great lengths to mimic the visual style of the Old Masters, using period-correct wood panels and convincing craquelure, but had failed to account for the molecular signature of the ground. This scientific oversight exposed the entire enterprise.

In December 2016, responding directly to the emergency, Sotheby’s acquired Orion Analytical and appointed James Martin as its Director of Scientific Research. This move signaled a permanent shift in the art market’s validation process, elevating molecular science above the traditional “connoisseurship” of art historians. The era where a trained eye alone could authenticate a multimillion-dollar masterpiece had ended; the new standard required that the chemistry of the paint align with the history of the artist.

The Eye vs. The Lab: Why Connoisseurship Failed to Detect the Frauds

The exposure of the Ruffini ring did not just reveal a criminal enterprise; it shattered the epistemological foundation of the Old Master market. For centuries, the attribution of multi-million dollar artworks relied primarily on “the eye”—the, accumulated knowledge of seasoned art historians who could purportedly distinguish a brushstroke by Frans Hals from a follower’s by looking. The Ruffini forgeries were weaponized against this very reliance. They were not cheap copies but “original fakes,” designed specifically to exploit the psychological blind spots of connoisseurship.

Giuliano Ruffini and his associates, including the suspected painter Lino Frongia, understood that experts crave discovery. The fakes were technically brilliant, frequently filling convenient gaps in an artist’s oeuvre or utilizing rare materials that dazzled the viewer into suspending disbelief. When the National Gallery in London displayed David with the Head of Goliath in 2014, curator Letizia Treves praised its “incredible power” and the “brilliant chromatic effect” of its lapis lazuli support. The sheer audacity of painting on a slab of semiprecious stone acted as a magician’s misdirection, blinding the expert eye to the absence of provenance before 2012. The material itself became the authentication.

This reliance on visual intuition proved catastrophic when tested against modern forensic science. The turning point came with the involvement of James Martin, founder of Orion Analytical (later acquired by Sotheby’s). Unlike art historians, Martin did not look at the soul of the painting; he looked at its molecular structure. His findings were not matters of opinion but of chemical fact. In the case of the Portrait of a Man attributed to Frans Hals, which had been declared a French national treasure, Martin’s analysis found phthalocyanine blue in the deep paint. This synthetic pigment was not invented until the 1930s, three centuries after Hals’s death. The “masterpiece” was chemically impossible.

The table details the specific scientific smoking guns that dismantled the attributions of the ring’s most high-profile sales.

| Artwork | Attributed To | The Connoisseur’s Verdict | The Lab’s Verdict (Orion Analytical / C2RMF) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Venus with a Veil | Lucas Cranach the Elder (dated 1531) | Authenticated by Dieter Koepplin; purchased by Prince of Liechtenstein for €7M. as a “perfect” addition to the oeuvre. | Forged Support: Painted on oak (Cranach used lime wood). Thermal Aging: Cracks inconsistent with natural aging; panel baked to induce craquelure. |

| Portrait of a Man | Frans Hals | Declared a “National Treasure” by France; authenticated by Louvre curators. Sold for $10M+ to Mark Weiss/Fairlight. | Anachronistic Pigment: Presence of Phthalocyanine Blue (invented 1930s) in ground. |

| Saint Jerome | Parmigianino (Circle of) | Exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (2014-2015); authenticated by Mario di Giampaolo. Sold at Sotheby’s for $842, 500. | Anachronistic Pigment: Phthalocyanine Green (modern synthetic) found in 21 different sample locations. |

| David with the Head of Goliath | Orazio Gentileschi | Exhibited at National Gallery, London (2014). Praised for “stunning” execution on rare lapis lazuli stone. | Material Distraction: The lapis lazuli support masked the absence of history. Post-scandal analysis identified it as a modern fabrication linked to the Ruffini studio. |

The failure of the experts was not technical; it was widespread. The “eye” is susceptible to confirmation bias—the desire to believe that a beautiful, homeless masterpiece has finally been found. The forgers provided the beauty; the market provided the greed. It was only when the “lab” bypassed the aesthetic surface to interrogate the physical reality of the objects that the illusion collapsed. The scandal forced a permanent shift in the industry: provenance and connoisseurship are no longer sufficient. Without a molecular passport, no Old Master is safe.

The Prince’s Loss: The Liechtenstein Collection and the Forged Venus

The seizure of the Venus with a Veil was more than a legal procedure; it was a direct strike against one of the world’s most prestigious private art holdings. For Prince Hans-Adam II of Liechtenstein, the acquisition of the panel in 2013 was meant to be a crowning addition to the Princely Collections, a repository of European masterpieces that rivals national museums. Instead, the 1531 panel became the centerpiece of a humiliation that exposed the fragility of expert authentication in the face of high-tech forgery.

The Prince had purchased the work for €7 million (approximately $9 million) from the venerable London gallery Colnaghi. The transaction appeared impeccable on paper. Colnaghi, then owned by Konrad Bernheimer, had acquired the painting just months earlier for €3. 2 million from a manager of an American investment fund. The rapid markup—more than doubling in price—was justified by the gallery as a market correction for a “rediscovered” masterpiece. The work came with the blessing of renowned Cranach scholars, including Werner Schade and Dieter Koepplin, who authenticated the panel based on stylistic analysis. For the Liechtenstein curators, the provenance seemed plausible, tracing back to a private Belgian collection in the 19th century. In reality, the trail led back to Giuliano Ruffini.

When French investigators from the OCBC removed the painting from the Caumont Centre d’Art, they did not just take a picture; they took a €7 million asset. The Prince’s reaction was immediate and furious. In a move that sent shockwaves through the French museum world, the Princely Collections suspended all loans to French institutions. “The Princely Collections were surprised by this seizure, which was not preceded by any discussion,” stated the Prince’s lawyer, Éric Morain. The diplomatic freeze threatened upcoming exhibitions at the Louvre and Versailles, leveraging the Prince’s massive cultural capital against the French state’s judicial.

The Forensic Battleground

The legal battle that ensued turned the Venus into a specimen for forensic warfare. The court-appointed experts at the Center for Research and Restoration of the Museums of France (C2RMF) subjected the panel to rigorous analysis, producing a report that dismantled the attribution to Cranach. The findings were technical, specific, and damning.

The primary evidence of forgery lay in the physical aging of the panel. Investigators discovered a “cracking network” in the paint that did not match natural centuries-old decay. Instead, the craquelure appeared consistent with “artificial ageing,” a process where the painting is baked in an oven to induce premature cracking. This technique, designed to fool the naked eye, failed under microscopic scrutiny, which revealed that the cracks were too uniform and deep, absence the organic randomness of 500-year-old oil paint.

Article image: Forged Masters: The European Gallery Scandal

Further analysis targeted the pigments. While the forger had been careful to use period-appropriate materials in areas, the chemical composition of the yellow paint used for Venus’s necklace raised alarms. The Liechtenstein collection’s own experts, including dendrochronologist Peter Klein, argued that the oak panel dated to approximately 1520, consistent with the 1531 date on the painting. They also fiercely contested the pigment analysis, asserting that the lead-tin yellow found was consistent with Renaissance palettes. yet, the prosecution’s experts identified anomalies in the lead isotopes and the presence of modern impurities that had no place in a 16th-century workshop.

| Metric | Details |

|---|---|

| Purchase Price (2013) | €7, 000, 000 (Sold to Prince of Liechtenstein) |

| Previous Price (2013) | €3, 200, 000 (Acquired by Colnaghi) |

| Original Seller | Giuliano Ruffini (via intermediaries) |

| Support Material | Oak panel (Cranach typically used lime wood) |

| Key Forensic Flaw | Artificial craquelure (baking) & pigment anomalies |

A Hollow Victory

The criminal investigation dragged on for five years, leaving the painting in legal limbo. In 2021, a Paris appeals court finally ordered the return of the Venus to the Prince of Liechtenstein. The ruling, yet, was not an exoneration of the painting but a procedural decision: the court determined that the Prince, having bought the work in good faith, was the rightful owner regardless of its authenticity. The painting was returned, but its reputation was shattered.

The Princely Collections continue to defend the work publicly, displaying it as a genuine Cranach and citing their own expert reports. Yet, the market consensus has shifted irrevocably. The Venus with a Veil stands as a cautionary symbol of the “Ruffini Affair,” a €7 million reminder that even the most well-funded and expert-backed collections are to the sophisticated alchemy of modern forgery.

The Parmigianino Dispute: The Metropolitan Museum of Art under scrutiny

The scandal that began in a provincial French gallery soon breached the walls of one of the world’s most prestigious institutions: The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. At the center of this transatlantic dispute was a small oil on panel depicting Saint Jerome, a work that had ascended from the murky “Circle of Parmigianino” to the exalted status of an autograph work by the Mannerist master himself. This elevation, validated by the Met’s curators, would serve as a humiliating case study in the failure of connoisseurship against forensic science.

In January 2012, Sotheby’s New York sold the Saint Jerome for $842, 500. The auction house catalogued the work cautiously as “Circle of Parmigianino,” a designation implying it was painted by a follower or studio assistant rather than Girolamo Francesco Maria Mazzola himself. The buyer, a private collector, believed the work held greater chance. Their optimism seemed justified when, in April 2014, the Metropolitan Museum of Art accepted the painting on loan. For ten months, the panel hung in the museum’s European Paintings galleries, its label upgraded to “attributed to Parmigianino.” This institutional endorsement multiplied the work’s market value, transforming a speculative purchase into a rediscovered masterpiece.

The Met’s embrace of the painting was not passive. A museum spokeswoman later confirmed that the work was accepted “for study” and that curators had discussed its attribution with leading scholars. Among those was Mary Vaccaro, a specialist who had included the work in her 2002 monograph. The museum’s validation provided the serious provenance and scholarly weight that dealers like Giuliano Ruffini—the work’s original source—relied upon to legitimize their inventory. The Saint Jerome was no longer just a painting; it was a Met-approved asset.

The illusion collapsed in 2016. Following the seizure of the Cranach Venus in France, Sotheby’s grew suspicious of other works linked to Ruffini. The auction house took the extraordinary step of recalling the Saint Jerome and submitting it to Orion Analytical, a materials analysis firm led by James Martin. The scientific verdict was absolute and devastating. Martin took 21 samples from various sites on the panel. Every single sample contained phthalocyanine green, a synthetic pigment created in 1936—four centuries after Parmigianino’s death in 1540.

| Test Subject | Methodology | Key Finding | Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pigment Samples | Micro-sampling (21 sites) | Presence of Phthalocyanine Green | Pigment invented in 1936; impossible for 16th-century work. |

| Binder Analysis | Chemical composition | Modern synthetic resin | Inconsistent with Renaissance oil binding media. |

| Attribution Status | Pre-Analysis | “Attributed to Parmigianino” (The Met) | High market value; institutional validation. |

| Attribution Status | Post-Analysis | Modern Forgery | Value reduced to zero; sale rescinded. |

The presence of a modern industrial pigment in a painting that had hung on the walls of the Met exposed a widespread vulnerability in the art world: the reliance on the “eye” of the connoisseur over the rigour of the lab. While art historians debated brushwork and composition, the chemical reality of the paint remained unchecked until the scandal forced a review. The Met, having displayed a forgery as a genuine Renaissance work, retreated into silence, stating only that the attribution had been a matter of scholarly debate.

The financial was immediate. Sotheby’s rescinded the 2012 sale and fully refunded the buyer. The auction house then turned its legal sights on the seller, Lionel de Saint Donat-Pourrières, a Luxembourg-based merchant who had consigned the work. In a lawsuit filed in the U. S. District Court for the Southern District of New York, Sotheby’s demanded repayment of the sale proceeds. Saint Donat-Pourrières attempted to challenge the forensic findings, hiring his own expert, Maurizio Seracini. In a twist that sealed the painting’s fate, Seracini concurred with Orion Analytical: the work was “without doubt a 20th-century fabrication.”

In November 2018, Judge George B. Daniels issued a default judgment against Saint Donat-Pourrières, who had withdrawn from the American legal proceedings. The court ordered him to pay Sotheby’s $1. 2 million, a sum covering the original sale price, interest, legal fees, and the cost of the forensic testing that proved the fraud. The judgment established a serious precedent: auction houses could and would claw back funds for works proven to be fakes, even years after the hammer fell. For the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the episode remains a quiet but permanent blemish, a reminder that in the modern art market, prestige is no substitute for provenance.

The Orazio Gentileschi Lapidation: A study in gallery complicity

The scandal surrounding the Ruffini ring reached the highest echelons of the British art establishment with the exposure of a small, dazzling work attributed to the Baroque master Orazio Gentileschi. Titled David Contemplating the Head of Goliath, the painting was not an oil on canvas but a technical marvel executed directly onto a slab of lapis lazuli. This choice of support—a semi-precious stone prized for its intense ultramarine hue—served as the forger’s masterstroke. It bypassed the need for complex background painting while simultaneously seducing experts with its material rarity. The “lapidation” of the art market was literal: a fake built on stone that fooled the world’s most venerable institutions.

Article image: Forged Masters: The European Gallery Scandal

In 2013, the National Gallery in London accepted the work on loan for its exhibition Making Colour. The gallery’s endorsement provided the imprimatur of authenticity, transforming a work with no pre-1990s provenance into a verified masterpiece. Curator Letizia Treves publicly praised the painting, describing its “incredible wall power” and the “emphatic juxtaposition” of the stone support. This institutional enthusiasm proceeded without the rigorous technical analysis that would later unravel the fraud. The gallery’s decision to display the work laundered its reputation, signaling to the market that the piece was beyond reproach.

The Mechanics of the Deception

The forgery relied on a sophisticated understanding of academic desire. By using a lapis lazuli support, the forger—suspected to be the Italian painter Lino Frongia—created an object that appeared “bizarre” yet historically plausible. The stone itself acted as a shield against standard dating methods like dendrochronology, which is used for wood panels. The painting’s emergence followed the standard Ruffini playbook: a “discovery” in a minor auction or private collection, followed by a rapid ascent through the hands of intermediaries to a major dealer.

| Year | Event | Key Entities Involved |

|---|---|---|

| 2012 | “Discovery” of the work | Giuliano Ruffini, Intermediaries |

| 2013 | Acquisition by London dealer | The Weiss Gallery |

| 2014 | Exhibition at National Gallery | National Gallery (London), Letizia Treves |

| 2016 | Scandal breaks; authenticity questioned | French OCBC, Vincent Noce |

| 2019 | Arrest warrants issued | Judge Aude Buresi, Lino Frongia |

The Weiss Gallery in London, a prominent Old Master dealer, handled the sale of the work to a private collector. Unlike the forged Frans Hals, which resulted in a swift $10 million refund from Sotheby’s, the Gentileschi case remained legally and financially unclear. The dealer maintained the work’s authenticity long after the scandal broke, citing the National Gallery’s display as evidence of its legitimacy. This circular logic—dealers citing museums, and museums relying on dealers—exposed a widespread failure in the vetting process for “newly discovered” Old Masters.

Institutional Silence and

When the French investigation identified the Gentileschi as a likely product of the Ruffini ring, the National Gallery faced severe criticism. Art critic Jonathan Jones, who had initially called the painting “bizarre” during its exhibition, later recanted his admiration, asking if the gallery had been “scammed.” The institution’s response was muted; a spokesperson stated they had “no obvious reasons to doubt” the attribution during the loan period. This defense highlighted a serious vulnerability: the reliance on connoisseurship over forensic science when the object fits a curator’s narrative.

The “David” on lapis lazuli remains a potent symbol of the scandal. It demonstrated that even the most technically astute forgeries rely less on chemical perfection than on social engineering. By exploiting the desire for rare materials and lost masterpieces, the forgers turned the expertise of curators into a weapon against the truth. The stone support, intended to signal eternal value, instead became the tombstone for the credibility of those who authenticated it.

Auction House Liability: The Contractual Minefield

The exposure of the Ruffini ring did not embarrass the world’s leading auction houses; it triggered a cascade of rescission demands that tested the ironclad contracts underpinning the art market. At the center of this legal storm was the “Authenticity Guarantee,” a standard clause in Sotheby’s and Christie’s conditions of sale. While frequently viewed by collectors as a safety net, the Ruffini scandal revealed these clauses to be complex legal method that could trap auction houses between aggrieved buyers demanding refunds and sellers refusing to return the proceeds.

Between 2016 and 2020, Sotheby’s found itself fighting a multi-front war to recover millions paid out for works that forensic science had subsequently declared “counterfeit.” The battle lines were drawn over specific contractual definitions: what constitutes a “counterfeit,” and crucially, what defines the “generally accepted views of scholars” at the time of sale.

The $10. 75 Million Frans Hals Dispute

The most significant legal test occurred in London’s High Court, centering on the Portrait of a Gentleman attributed to Frans Hals. Sotheby’s had sold the work in 2011 to American property developer Richard Hedreen (via his company EPC Nevada) for $10. 75 million. Following the 2016 raid and subsequent forensic analysis by Orion Analytical—which found modern synthetic pigments in the paint —Sotheby’s rescinded the sale and refunded Hedreen in full.

yet, the sellers—London dealer Mark Weiss and his investment partner, Fairlight Art Ventures—refused to reimburse the auction house. The ensuing litigation, Sotheby’s v. Mark Weiss Ltd & Ors, exposed the mechanics of high- art finance.

| Party | Role | Financial Liability / Action |

|---|---|---|

| Sotheby’s | Agent / Auction House | Refunded buyer $10. 75 million in 2016 |

| Mark Weiss Ltd | Seller (Dealer) | Settled for $4. 2 million before 2019 trial |

| Fairlight Art Ventures | Seller (Investor) | Ordered to pay approx. $5. 3 million + costs |

| EPC Nevada | Buyer | Received full refund; returned painting |

The defense hinged on the “Generally Accepted Views” (GAV) proviso. This clause protects sellers from liability if the auction house’s description of the lot accorded with the generally accepted views of scholars at the date of the sale, even if that view later changes. Fairlight argued that because experts had praised the painting in 2011, the sale should stand. The Court of Appeal rejected this in 2020, ruling that because the work was “newly discovered” and had not been physically examined by a consensus of experts, no “generally accepted view” existed. The judgment forced Fairlight to repay its share of the proceeds, establishing a precedent that investors in art deals are “principals” to the consignment and share liability for fakes.

The Parmigianino Precedent

A similar played out in New York regarding the fake Saint Jerome attributed to Parmigianino. Sotheby’s had sold the work in 2012 for $842, 500. After Orion Analytical identified the presence of phthalocyanine Green—a pigment not invented until 1936—Sotheby’s rescinded the sale in 2015.

The seller, Lionel de Saint Donat-Pourrières, refused to return the funds. In 2018, a U. S. District Court ordered him to repay the auction house $1. 2 million, a sum covering the original sale price, interest, legal fees, and the cost of the forensic testing. This ruling reinforced the auction house’s power to unilaterally determine authenticity based on scientific evidence, a right explicitly reserved in their conditions of business.

Christie’s and the “Doubts” Defense

While Sotheby’s litigated, Christie’s largely avoided the direct financial of the Ruffini scandal through caution. Reports confirmed that Christie’s Paris had been offered the same Frans Hals in 2008 but declined to sell it. The auction house’s specialists harbored “doubts” about the attribution and provenance, specifically the absence of a documented history prior to Ruffini. Similarly, the Venus with a Veil attributed to Lucas Cranach the Elder—later sold by Colnaghi to the Prince of Liechtenstein for €7 million—had reportedly been rejected by Christie’s due to inconclusive tests.

This highlights a serious variance in risk appetite. Christie’s refusal to consign the works protected them from the rescission demands that later entangled their rival. The Prince of Liechtenstein, unlike the buyers at Sotheby’s, did not have the recourse of an auction house authenticity guarantee for his private purchase. Instead of accepting a refund and returning the work, the Prince’s collection maintained the Cranach’s authenticity, engaging in a protracted legal battle to recover the seized painting from French authorities, which they finally achieved in 2021.

The Lino Frongia Connection: The Hand Behind the Masters

While Giuliano Ruffini operated as the charismatic frontman of the operation—charming curators and placing works in princely collections—investigators believe the technical wizardry originated in the studio of a quiet, respected painter in Northern Italy. Pasquale “Lino” Frongia, a graduate of the Fine Arts Academy of Bologna, emerged in 2016 as the primary suspect accused of physically creating the forgeries that fooled the world’s top experts.

Frongia does not fit the profile of a criminal mastermind. Born in 1958 in Montecchio, Emilia-Romagna, he established a legitimate reputation as a Neo-Mannerist painter, known for works influenced by De Chirico’s “magic realism” and technical proficiency that rivaled the Old Masters he studied. His skill in replicating the brushwork of Titian, Rubens, and El Greco was not a secret; it was his calling card. yet, French investigators allege that this talent was weaponized to produce the “Ruffini Old Masters,” including the Cranach Venus, the Frans Hals Portrait of a Man, and the El Greco Saint Francis.

The Smoking Gun: The Swiss Transfer

The link between the painter and the salesman was cemented by financial records uncovered by the Central Office for the Fight Against Cultural Goods Trafficking (OCBC). Investigators traced a wire transfer of €740, 000 ($800, 000) sent to Frongia’s Swiss bank account by Mathieu Ruffini, Giuliano’s son.

When pressed by authorities, Frongia claimed the payment was for legitimate “sales and restoration work” performed for the Ruffini family. Yet, the magnitude of the sum—far exceeding standard restoration fees—raised immediate red flags. This financial trail provided the OCBC with the hard evidence needed to secure European arrest warrants.

The El Greco Seizure

Frongia’s direct involvement in the trade of these works was exposed during an exhibition in Treviso in 2016. The show, titled El Greco in Italy, featured a painting of Saint Francis loaned by none other than Lino Frongia himself. Acting on a European Investigation Order, Italian police seized the painting from the gallery wall on the exhibition’s final day.

Frongia maintained the work was a genuine masterpiece he had purchased. yet, forensic analysis later revealed the presence of modern pigments inconsistent with the 16th century, mirroring the anomalies found in the Cranach Venus. This seizure marked the time Frongia was publicly identified not just as an associate of Ruffini, but as a trafficker of the works in his own right.

The Sgarbi Factor and the “Torch” Scandal

Frongia’s defense has been vocally supported by Vittorio Sgarbi, a controversial Italian art critic and former Undersecretary of Culture. Sgarbi has repeatedly attested to Frongia’s innocence, describing him as “the greatest living Old Master.” yet, this relationship faced scrutiny in 2024 during a separate investigation involving a 17th-century painting by Rutilio Manetti.

Italian prosecutors alleged that a stolen Manetti canvas, The Capture of Saint Peter, had been altered to disguise its origins. The alteration involved the addition of a torch to the composition—a detail absent in the original stolen work. In October 2024, reports surfaced that Frongia had admitted to prosecutors that he added the torch at Sgarbi’s request. This admission of altering an Old Master to change its identity struck a devastating blow to his credibility regarding the Ruffini forgeries.

Legal Standoff: The Extradition Battle

The legal of Frongia has been a diplomatic tug-of-war between France and Italy.

| Date | Action | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| September 2019 | European Arrest Warrant issued by Judge Aude Buresi. | Arrested in Emilia-Romagna. Released in Feb 2020 after Bologna court “inconsistent charges.” |

| December 2022 | Giuliano Ruffini extradited to France. | Ruffini charged with gang fraud; pressure mounts on Frongia. |

| June 2023 | Second European Arrest Warrant issued. | Re-arrested by Carabinieri in Montecchio. |

| October 2024 | Manetti/Sgarbi Investigation. | Frongia implicated in altering a stolen painting; extradition to France still stalled. |

even with the 2023 arrest, Italian courts have resisted extraditing Frongia to Paris, a sharp contrast to the fate of Giuliano Ruffini, who was delivered to French authorities in late 2022. While Ruffini sits under house arrest in Paris facing charges of gang fraud and money laundering, Frongia remains in Italy. The refusal to extradite hinges on technicalities of Italian law regarding the specific evidence presented by the French judge, leaving the “Moriarty” of the operation out of reach of the primary prosecution, even as the evidence of his craftsmanship piles up in forensic labs across Europe.

Market Contagion: The Collapse of Trust in the Old Master Sector

The seizure of the Cranach Venus did not remove a single painting from a gallery wall; it punctured the hermetic seal of confidence that sustains the high-end art trade. By mid-2016, the that a sophisticated forgery ring had chance infiltrated the collections of the Prince of Liechtenstein, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the National Gallery created a phenomenon dealers termed “market contagion.” The presumption of authenticity, once the bedrock of Old Master transactions, inverted overnight. Works were no longer innocent until proven guilty; they were suspect until proven scientifically unimpeachable.

The immediate financial impact was catastrophic. In the half of 2016, Christie’s reported a 33% decline in Old Master sales compared to the previous year. While the auction house publicly attributed this to a “supply absence,” internal memos and market analysis from ArtTactic revealed a darker reality: buyers were paralyzed. The fear was not limited to works directly linked to Giuliano Ruffini; it metastasized to any painting absence an ironclad, multi-century paper trail. A “flight to quality” became a flight to safety, with capital aggressively pivoting toward the Impressionist and Contemporary sectors, where provenance is easier to verify and forensic dating is less ambiguous.

The case of the David Contemplating the Head of Goliath, attributed to Orazio Gentileschi, exemplifies how this contagion breached the highest citadels of expertise. Displayed proudly by London’s National Gallery in 2014, the work was later revealed to be another Ruffini-linked object. When a institution of such standing—armed with conservators and scholars—could be deceived by a modern fabrication on lapis lazuli, the private collector ceased to trust their own eyes. The National Gallery’s silent withdrawal of the work did little to quell the panic; it confirmed that the gatekeepers were asleep.

| Metric | 2015 (Pre-Scandal Peak) | 2016-2017 (Scandal Impact) | 2024 (Long-term Trend) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Christie’s Old Master Sales (H1) | £2. 9 billion (Global Art Total) | -33% decline in category revenue | Continued stagnation |

| European Old Master Market Size | $1. 63 billion (Global) | Sharp contraction in volume | $384 million (Record Low) |

| Key Forgery Refunds | N/A | $10. 75m (Sotheby’s / Frans Hals) | Ongoing litigation |

| Buyer Sentiment | Stable / Traditional | “emergency of Confidence” | Shift to Contemporary |

The contagion forced auction houses into a defensive posture in their history. Sotheby’s, reeling from the $10. 75 million refund paid to Richard Hedreen for the fake Frans Hals, took the drastic step of acquiring Orion Analytical in late 2016. By bringing James Martin—the forensic scientist who identified the synthetic phthalocyanine green in the Hals and Parmigianino forgeries—in-house, Sotheby’s admitted that connoisseurship was dead. The “eye” of the expert was no longer sufficient collateral for a multimillion-dollar loan or sale; only the mass spectrometer could underwrite the market.

This shift imposed a “forensic tax” on the sector. Sellers of legitimate works faced new, invasive demands for pigment analysis and dendrochronology (wood dating) before consignments were accepted. The friction slowed the pipeline of genuine masterpieces, the supply crunch. In December 2021, even as the market attempted to recover, Christie’s and Sotheby’s London evening sales grossed a combined £29. 3 million—a nearly 20% drop from pre-pandemic levels. The “Ruffini effect” had permanently altered the risk profile of the Old Master category, turning it into a niche market for the brave, while the speculative money moved permanently to Basquiat and Banksy.

The collapse was not financial but existential. The scandal demonstrated that the market’s method for truth-telling—scholarship, museum exhibition, and auction house vetting—were widespread failures against a forger who understood that the industry wanted to believe in miracles more than it wanted to check the chemistry.

The French Investigation: Judge Aude Buresi and the Criminal Probe

By 2015, the whispers surrounding Giuliano Ruffini’s “discoveries” had coalesced into a formal criminal inquiry led by Judge Aude Buresi of the Paris Tribunal de Grande Instance. Unlike the civil disputes characterizing the Sotheby’s and Christie’s battles, Buresi’s mandate was penal: she was hunting for a gang fraud operation. Her investigation, as a probe into “organized gang fraud” and “money laundering,” pierced the veil of the Old Master market, transforming a series of attribution errors into a hunt for a sophisticated criminal enterprise.

Buresi’s strategy was aggressive. Following the March 2016 seizure of the Cranach Venus in Aix-en-Provence, she ordered a forensic of the artwork that sent shockwaves through the dealer community. The Center for Research and Restoration of the Museums of France (C2RMF), housed in the Louvre, was tasked with the analysis. While their final report on the Venus remained a battleground of interpretation—with experts arguing the data was “inconclusive”—other seized works provided the scientific smoking guns the prosecution needed.

The forensic breakthrough came not from the Venus alone, but from the broader inventory linked to Ruffini. Analysis of a Portrait of a Man attributed to Frans Hals, which had passed through Ruffini’s hands to a Seattle collector, revealed the presence of titanium white—a pigment not commercially available until the 1920s. Furthermore, investigators found traces of “plastic-coated air abrasive” in the paint, a material used in modern sandblasting, completely anachronistic for a 17th-century Dutch master. These findings suggested a factory-like production line where modern materials were chemically aged to fool the naked eye.

“The presence of titanium white in a purported 17th-century work is not an anomaly; it is a confession of forgery written in chemistry.”

In her of the source, Buresi turned her sights to Lino Frongia, the Emilian painter long suspected of being the brush behind the operation. In 2019, she issued European arrest warrants for both Giuliano Ruffini and Frongia. The warrants alleged that Ruffini acted as the marketing mastermind while Frongia provided the technical wizardry. A raid on Ruffini’s property in Reggio Emilia yielded a piece of circumstantial evidence that became legendary in the press: a large industrial oven, which investigators theorized was used to “bake” fresh oil paintings to induce premature cracking, mimicking centuries of age.

The legal battle for extradition was protracted. For years, Italian courts resisted handing over the suspects. In February 2020, a Bologna court rejected the warrant for Frongia, citing inconsistent evidence. yet, Buresi. In December 2022, the legal dam broke: Giuliano Ruffini was finally extradited to Paris. Upon his arrival, he was indicted on charges of gang fraud and money laundering and placed under house arrest. Six months later, in June 2023, Italian authorities arrested Frongia again under a new European warrant issued by Buresi, signaling a renewed offensive in the case.

| Date | Event | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| March 2016 | Seizure of Cranach’s Venus | Public confirmation of criminal probe; C2RMF analysis ordered. |

| May 2019 | European Arrest Warrants Issued | Buresi formally Ruffini and Frongia for extradition. |

| February 2020 | Bologna Court Rejection | Italian judges refuse to extradite Frongia; investigation stalls. |

| December 2022 | Ruffini Extradited to France | Mastermind charged with gang fraud and money laundering in Paris. |

| June 2023 | Second Arrest of Lino Frongia | New warrant executed in Emilia, reviving the of the forger. |

As of late 2024, the investigation remains active, with Buresi’s office continuing to compile evidence for a chance mega-trial. The inquiry has expanded to scrutinize the network of intermediaries—experts, curators, and smaller dealers—who validated these works. Buresi’s probe suggests that the “Forged Masters” were not the work of a solitary genius, but the product of a complicit ecosystem that prioritized profit over provenance.

Laundering Through Art: Using forged masters to clean illicit capital

The allure of the Old Master market for financial criminals lies not in the brushstrokes, but in the opacity of the transaction. While the public scandal focused on the deception of museums and collectors, investigators from the Central Office for the Fight Against Cultural Goods Trafficking (OCBC) and the US Department of Justice uncovered a parallel utility for these forged works: they served as highly vehicles for laundering illicit capital. Between 2015 and 2025, the intersection of high- forgery and money laundering evolved from simple fraud—hiding the proceeds of a fake sale—into complex schemes where the artwork itself acted as a fabrication of value, allowing dirty money to enter the legitimate financial system under the guise of cultural arbitrage.

In the case of the Ruffini ring, the financial architecture was as carefully constructed as the craquelure on the panels. French investigators, led by Judge Aude Buresi, traced a network of payments that bore the classic hallmarks of —the stage of money laundering designed to distance funds from their illegal source. The sale of the Venus with a Veil, attributed to Lucas Cranach the Elder, was not a direct transaction between artist and collector. Instead, the work moved through a nebulous entity known as “The Art Factory.” Records indicate Ruffini sold the work to this intermediary for €510, 000, a fraction of its €7 million sale price to the Prince of Liechtenstein. This initial low-value transfer created a paper trail of legitimate acquisition, allowing the subsequent markup to appear as capital appreciation rather than the proceeds of a crime.

The investigation into Ruffini’s financial flows revealed the specific mechanics used to distribute these proceeds. Bank records seized by authorities showed that Mathieu Ruffini, Giuliano’s son, transferred approximately €740, 000 from a UBS Swiss account to Lino Frongia, the painter alleged to have created the works. To bypass anti-money laundering (AML) triggers, these payments were not flagged as commissions for new works—which would raise questions about the “Old Master” provenance—but were instead disguised as fees for “restoration” and legitimate sales of minor works. This misclassification allowed the network to reintegrate the fraud’s profits into the Italian banking system as clean business income.

| Case / Network | method Used | Asset Involved | Laundered Amount (Est.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ruffini Ring (France/Italy) | via “restoration” fees and intermediaries | Forged Old Masters (Cranach, Hals) | €220 Million (Total Fraud Value) |

| Beaufort Securities (UK/US) | Phantom sale / Stock fraud cleaning | Picasso Personnages (Fraudulent Paperwork) | £6. 7 Million |

| Eurojust Network (EU-wide) | Complicit auction houses & fake catalogues | 2, 100+ Fake Warhols/Banksys | €200 Million (chance Damage) |

The utility of art as a laundering vessel was further exposed in the 2018 indictment of London art dealer Matthew Green. While distinct from the Ruffini ring, the Green case provided the blueprint for how “phantom sales” of masterworks—real or forged—clean dirty cash. Green was charged by US authorities for attempting to launder £6. 7 million for an undercover agent posing as a stock manipulator. The scheme involved the sale of a Picasso, Personnages (1965). Crucially, the painting was never intended to change hands physically. Green proposed drafting false ownership papers to simulate a sale, allowing the “buyer” to transfer illicit funds to the gallery. The gallery would then “buy back” the work at a lower price, returning the money as clean legitimate proceeds from an art deal, minus a laundering fee. Forgers adapted this method: by using a fake painting with zero intrinsic value, they could execute similar wash trades without risking a genuine multi-million dollar asset.

The of such operations was laid bare in November 2024, when a massive European operation coordinated by Eurojust dismantled a network spanning Italy, Spain, France, and Belgium. Authorities arrested 38 individuals and seized over 2, 100 forged works attributed to modern masters like Banksy, Warhol, and Picasso. Unlike the boutique operation of the Old Master forgers, this network industrialized the laundering process. They utilized complicit auction houses to publish catalogues featuring the fakes, creating a public record of value. By selling these works through legitimate auctions, the network converted the manufacturing cost of the fakes—negligible materials—into verified auction house checks, the gold standard of clean capital. The investigation estimated the chance economic damage at €200 million, highlighting how the volume of forgeries serves as a massive engine for financial integration.

These cases demonstrate that the forged master is not a fraudulent object but a financial instrument. In the hands of a launderer, a fake painting is a bearer bond with a subjective value. It allows criminals to move vast sums across borders, bypass banking compliance, and explain sudden influxes of wealth as the stroke of luck in a volatile market. The “restoration” payments to Frongia and the shell company invoices in the Ruffini affair were not just administrative details; they were the essential gears of a machine designed to turn paint into clean cash.

The Role of Freeports: Hiding Dubious Inventory in Geneva and Singapore

The “Forged Masters” scandal did not operate in a vacuum; it relied on a global infrastructure of opacity designed to sever artworks from their history. At the heart of this system were freeports—maximum-security storage facilities in Geneva, Singapore, and Luxembourg that function as extraterritorial zones where art can be bought, sold, and stored without customs duties or transaction taxes. For the network moving the Ruffini forgeries, these facilities were not warehouses; they were black boxes where “fresh” Old Masters could emerge from the void, stripped of scrutiny, and prepared for market entry.

The method of obfuscation was exposed in 2015, not by a forgery investigation, but by the arrest of Yves Bouvier, the so-called “Freeport King.” Bouvier, who owned major in the Geneva Freeport and established the Singapore Freeport (frequently called “Asia’s Fort Knox”), was detained in Monaco following allegations of fraud by Russian oligarch Dmitry Rybolovlev. While the Bouvier affair centered on price inflation, it shattered the seal of silence protecting these zones. It revealed a world where inventory lists were nonexistent, ownership was obscured by shell companies, and paintings could change hands multiple times without ever leaving the vault.

This environment was the ideal incubator for the works associated with Giuliano Ruffini. The Saint Jerome, attributed to Parmigianino and sold at Sotheby’s New York in 2012 for $842, 500, was consigned by Lionel de Saint Donat-Pourrières, a broker based in Luxembourg—home to another high-security freeport opened by Bouvier in 2014. When the painting was later declared a “modern forgery” by Orion Analytical in 2018, the court documents highlighted the complex, cross-border movement of the work, facilitated by the unclear logistics networks that freeports anchor. The absence of a verifiable paper trail, a hallmark of freeport transactions, allowed the painting’s sudden appearance to be framed as a “rediscovery” rather than a fabrication.

In Geneva, the oldest and largest of these facilities, the inventory is estimated to hold over 1. 2 million works of art. Following the 2016 “Panama Papers” leak, which linked the freeport to the Nazi-looted Seated Man with a Cane by Modigliani, Swiss authorities were forced to act. On January 1, 2016, the Swiss Customs Act was amended to require an inventory of owners for goods stored in freeports, a direct response to the reputational risk posed by scandals involving looted antiquities and forged masters. This regulatory tightening sent shockwaves through the market, forcing dealers to either declare their holdings or move them to less regulated jurisdictions.

| Year | Jurisdiction | Action / Event | Impact on Market |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | Monaco / Singapore | Arrest of Yves Bouvier | Exposed the inner workings of the freeport system; triggered global scrutiny. |

| 2016 | Switzerland | Swiss Customs Act Amendment | Mandated 6-month time limit on “export” goods; required owner identification. |

| 2018 | European Union | European Parliament “TAX3” Report | Labeled freeports as high-risk zones for money laundering and tax evasion. |

| 2020 | EU / Global | 5th Anti-Money Laundering Directive | Extended AML obligations to art dealers and freeport operators. |

| 2022 | Singapore | Sale of Le Freeport | Sold for $28M (a massive loss from $100M cost) to crypto-billionaire Jihan Wu. |

The Singapore Freeport, opened in 2010 near Changi Airport, was intended to be the Asian hub for this trade. yet, the global crackdown on tax evasion and the specific heat from the Bouvier and Ruffini scandals turned the facility into a liability. By 2019, the facility was reportedly losing money, and in September 2022, Bouvier sold the Singapore Freeport to Jihan Wu, a Chinese cryptocurrency billionaire, for SGD 40 million (approx. $28 million)—a fraction of its $100 million construction cost. The fire sale marked the end of an era where art could be stored indefinitely in a legal limbo, shielded from the inquiries of provenance researchers and law enforcement.

The collapse of the freeport model’s secrecy has been serious in tracing the “Forged Masters.” Without the ability to hide the physical location and ownership history of these panels, the network’s ability to introduce new fakes has been severely. The 2016 seizure of the Cranach Venus in France was a physical manifestation of this new transparency; the painting was not hidden in a Geneva vault but was on public display, making it to the judicial warrant that eventually exposed its modern pigments.

The chart illustrates the correlation between the tightening of freeport regulations and the decline in “fresh” Old Master discoveries entering the market from unclear sources.

“The freeport was never just a storage facility. It was a jurisdiction of its own, designed to turn art into a bearer bond—anonymous, untraceable, and liquid. When that secrecy broke, the of the forgery ring broke with it.” — European Financial Crimes Investigator, 2019.

Institutional Blindness: The Louvre and the National Gallery Defenses

The scandal exposed a widespread failure within Europe’s most hallowed cultural institutions, revealing that the desire for discovery had eclipsed the rigor of verification. For decades, the art market relied on the “eye” of the connoisseur—a subjective validation by renowned scholars that could turn an unknown canvas into a multimillion-dollar asset. The Ruffini affair shattered this tradition, proving that even the world’s premier museums could be seduced by forgeries that, scientifically, were not even close calls.

The most damning indictment of this institutional blindness occurred in Paris. In 2008, the Louvre, guided by its curators, declared the Portrait of a Man attributed to Frans Hals a “National Treasure” (Trésor National). This classification is reserved for works of major heritage importance and legally blocks their export to allow the state time to acquire them. Blaise Ducos, the Louvre’s curator of Dutch and Flemish paintings, championed the work, describing it as a “masterpiece painted by the great Dutch artist” and a important addition to the canon. The French government launched a national fundraising campaign to generate €5 million to purchase the portrait. The acquisition only failed because the museum could not raise the funds during the financial emergency, not because of any forensic doubt. The Louvre had authenticated a modern fake, bestowing upon it the highest possible state honor based almost entirely on stylistic assessment.

Across the channel, the National Gallery in London demonstrated a similar lapse in due diligence. In 2013, the museum included a painting of David with the Head of Goliath, attributed to Orazio Gentileschi, in its major exhibition “Making Colour.” The work, painted on a clear slab of lapis lazuli, was another Ruffini discovery. even with the National Gallery’s reputation for technical prowess, the institution displayed the work without conducting the detailed scientific analysis that would have likely flagged anomalies. By placing the painting on its walls, the National Gallery implicitly endorsed its authenticity, inflating its market value and credibility. When the scandal broke, the museum adopted what critics termed an “ostrich defense,” retreating into silence rather than publicly addressing how a modern forgery bypassed its vetting.

The defense offered by these institutions—and the dealers who supplied them—hinged on the limitations of connoisseurship. Giuliano Ruffini consistently maintained that he never claimed the works were by Old Masters; he simply presented them to experts who, eager for a discovery, applied the attributions themselves. This defense weaponized the arrogance of the art establishment against itself. When scientific analysis finally occurred, the results were indisputable. James Martin of Orion Analytical found that the “National Treasure” Hals contained phthalocyanine blue, a pigment not created until the 1930s, and titanium white, which did not exist in the 17th century. Furthermore, he discovered traces of plastic-coated air abrasive materials in the paint, a clear sign of modern artificial aging techniques.

The financial was immediate for the market intermediaries, while the museums largely evaded direct monetary penalty but suffered reputational damage. Sotheby’s, which had sold the Hals and a fake Saint Jerome attributed to Parmigianino, was forced to rescind the sales and litigate against the sellers to recover millions. The auction house subsequently acquired Orion Analytical, admitting that the “eye” of the expert was no longer sufficient protection against high-level fraud.

Financial Impact of the Ruffini Forgeries

| Artwork | Attribution | Sale Price / Valuation | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Portrait of a Man | Frans Hals | $10, 750, 000 | Sotheby’s refunded buyer; declared “modern forgery” by court. |

| Venus with a Veil | Lucas Cranach the Elder | €7, 000, 000 | Seized by French authorities; Prince of Liechtenstein refunded. |

| Saint Jerome | Circle of Parmigianino | $842, 500 | Sotheby’s refunded buyer; Orion Analytical proved modern pigments. |

| David with the Head of Goliath | Orazio Gentileschi | Undisclosed (High Value) | Exhibited at National Gallery; later identified as suspect. |

The “Pascucci” Connection: Fabricating History

While the seizure of the Cranach Venus at the Caumont Centre d’Art garnered headlines, the underlying of the scandal relied on a sophisticated narrative strategy: the exploitation of historical looting to mask modern creation. Central to this deception was the figure of Pasquale “Lino” Frongia—frequently misidentified in early reports or conflated with minor associates under the moniker “Pascucci”—whose role extended beyond the easel to the construction of plausible deniability. Investigators found that the “Pascucci” angle was not a single individual but a method: a deliberate conflation of forged works with the chaotic dispersal of genuine collections during the 20th century.