The Tigers Purge: Xi Jinping’s Record Anti-Corruption Drive In Last 10 Years

The assumption that Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign would decelerate after he secured a historic third term has been shattered by the raw data of the last thirty-six months. Far from stabilizing, the “self-revolution” has metastasized into a permanent, intensifying state of governance. The numbers for 2025 are final, and they paint a picture of a party eating its own tail with ferocity: the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI) detained a record 65 “tigers”—senior officials at the vice-ministerial rank or above—in 2025 alone. This figure represents a 12 percent increase over the 58 tigers ensnared in 2024, which itself smashed the 2023 record of 45. The trajectory is undeniable. In the decade of the campaign, the focus was frequently interpreted as factional warfare—removing rivals like Bo Xilai and Zhou Yongkang. Today, the blade of “The Tigers Purge” falls on Xi’s own handpicked loyalists, signaling a terrifying new phase where proximity to the core offers no immunity.

The Acceleration of Elite Takedowns

The sheer volume of investigations at the highest echelons of the Communist Party of China (CPC) contradicts any narrative of “mission accomplished.” The CCDI’s dragnet has widened from traditional graft—bribery and embezzlement—to nebulous political crimes involving “disloyalty” and “forming cliques.” The following table illustrates the escalation of high-level purges over the last decade, highlighting the sharp spike following the 20th Party Congress.

| Year | “Tigers” Investigated | Notable / Sectors |

|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 37 | Security apparatus, Zhou Yongkang network |

| 2016 | 26 | State-owned enterprises (SOEs) |

| 2017 | 18 | Pre-19th Congress stabilization |

| 2018 | 23 | Financial sector initialization |

| 2019 | 20 | Inner Mongolia coal corruption |

| 2020 | 18 | Law enforcement apparatus |

| 2021 | 25 | Financial regulators, grain system |

| 2022 | 32 | Semiconductor industry, “Big Fund” |

| 2023 | 45 | PLA Rocket Force, Defense Minister Li Shangfu |

| 2024 | 58 | Finance, Tobacco, Sports, Defense Minister Wei Fenghe |

| 2025 | 65 (Record) | PLA Central Military Commission, Aerospace |

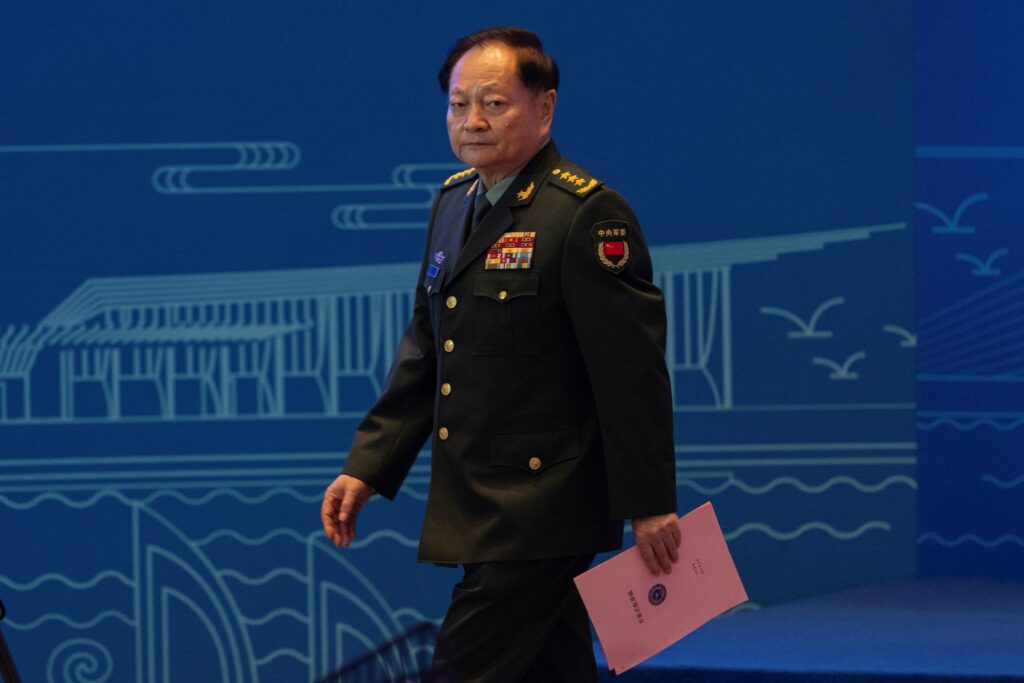

Decapitating the Military

The most volatile front of this rectification is the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). The purge of the Rocket Force—the custodians of China’s nuclear arsenal—has been absolute. In a span of eighteen months, the force saw three commanders and political commissars removed. The corruption scandal, centered on procurement fraud and leakage of secrets, claimed two consecutive Defense Ministers: General Wei Fenghe and General Li Shangfu. Both were stripped of their titles and expelled from the party, accused of accepting massive bribes and “betraying the original mission.” The shockwaves continued into January 2026 with the reported removal of General Zhang Youxia, the senior Vice Chairman of the Central Military Commission (CMC) and a lifelong associate of Xi. Zhang’s downfall, if fully confirmed by criminal proceedings, would mark the single most significant military purge since the Lin Biao incident in 1971. It suggests that the rot in the equipment development sector was not an tumor but a widespread failure involving the highest uniformed officers in the country.

The “Flies” Swarm

While the tigers grab headlines, the campaign against “flies”—lower-level functionaries—has reached industrial. In 2025, disciplinary inspection agencies across China punished 983, 000 individuals. This mass disciplining serves a dual purpose: it terrorizes the bureaucracy into compliance and channels populist anger against local corruption. The CCDI’s 2024 work report emphasized that the fight is “grave and complex,” a phrase that has appeared in every major communiqué for ten years. The difference is the target. The investigation of 3, 900 disciplinary cadres themselves in 2024 proves that the inquisitors are also on the chopping block. The “knife blade inward” policy means the purge is a closed loop, feeding on the very apparatus designed to enforce it. This “forever purge” has fundamentally altered the calculus of Chinese officialdom. Inaction is punished as “lazy governance,” while action carries the risk of mistakes labeled as corruption. The result is a paralyzed bureaucracy that looks only upward for survival, waiting for the tiger to fall.

Decapitating the Rocket Force: The Nuclear Arsenal Scandal

The corruption purge within the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Rocket Force represents the most severe decapitation of a strategic military branch in the history of the People’s Republic. Between July 2023 and June 2024, Xi Jinping systematically dismantled the command structure responsible for China’s nuclear deterrent. This was not a routine anti-graft operation; it was an emergency intervention triggered by intelligence indicating that the arsenal itself was compromised. The removal of two consecutive Defense Ministers—Wei Fenghe and Li Shangfu—alongside the entire Rocket Force leadership tier, exposed a emergency of confidence in the PLA’s ability to fight.

In July 2023, the sudden removal of Rocket Force Commander Li Yuchao and Political Commissar Xu Zhongbo marked the beginning of the collapse. Both men were stripped of their positions without initial explanation, only to be replaced by outsiders from the Navy and Air Force—a clear signal that the internal Rocket Force hierarchy was viewed as wholly contaminated. The investigation rapidly widened. By June 2024, the Communist Party expelled both Li Shangfu and his predecessor Wei Fenghe for “serious violations of discipline,” a euphemism that covered allegations of massive bribery and, more worrying, dereliction of duty in equipment procurement.

Article image: The ‘Tigers’ Purge: Xi Jinping’s Record Anti-Corruption Drive

The specific nature of the corruption allegations shocked defense analysts. U. S. intelligence assessments, leaked in early 2024, reported that widespread graft had materially degraded the PLA’s combat readiness. Reports indicated that fuel tanks in missiles were filled with water rather than propellant and that vast fields of missile silos in western China were fitted with defective lids that would prevent launch. These technical failures suggested that funds allocated for the rapid expansion of China’s nuclear triad had been siphoned off by a network of officers and contractors. The scandal proved that the “peace disease”—a term Xi uses for military complacency—had mutated into active sabotage through greed.

The purge did not stop at the top. In July 2024, the Central Committee expelled Lieutenant General Sun Jinming, the Rocket Force’s Chief of Staff, confirming that the rot extended through the operational planning levels. The investigation implicated the Equipment Development Department, the entity responsible for procuring the PLA’s hardware, retroactively targeting procurement bids dating back to 2017. This dragnet ensnared dozens of senior generals and defense industry, creating a paralysis in decision-making as officials feared any signature on a contract could lead to detention.

| Official | Position | Action Date | Key Allegations/Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wei Fenghe | Defense Minister (2018–2023) | Expelled June 2024 | Accepted unauthorized gifts; collapsed the equipment integrity of the Rocket Force. |

| Li Shangfu | Defense Minister (2023) | Expelled June 2024 | Bribery in equipment procurement; removed after only 7 months in office. |

| Li Yuchao | Rocket Force Commander | Removed July 2023 | Oversaw the force during period of reported “water-filled” missiles scandal. |

| Xu Zhongbo | Rocket Force Political Commissar | Removed July 2023 | Failed to enforce political discipline; removed alongside Commander Li. |

| Sun Jinming | Rocket Force Chief of Staff | Expelled July 2024 | Implicated in operational corruption; alternate member of Central Committee. |

The data from 2025 confirms that the military purge has not decelerated. The detention of 65 senior officials in 2025, surpassing the records of previous years, indicates that the “poison” Xi vowed to extract remains deep within the system. The Rocket Force scandal shattered the assumption that the PLA’s modernization drive was immune to the transactional culture of the past. By placing the nuclear arsenal under the command of officers with no missile experience, Xi prioritized political loyalty over technical expertise, a trade-off that questions the operational timeline of China’s strategic ambitions.

The Case of the Missing Ministers: Li Shangfu and Qin Gang

The assumption that loyalty to Xi Jinping guarantees political survival was dismantled in 2023 and 2024 with the abrupt, unexplained removals of two of China’s most prominent state councilors. The purges of Foreign Minister Qin Gang and Defense Minister Li Shangfu—both handpicked by Xi for his third-term leadership cadre—represent a spectacular failure of the party’s internal vetting method. These were not holdovers from rival factions; they were Xi’s own loyalists, elevated rapidly only to be erased from the political map with equal speed.

Qin Gang, the former ambassador to the United States and a celebrated “Wolf Warrior” diplomat, from public view on June 25, 2023. His erasure was absolute. For a month, the Foreign Ministry offered no credible explanation, initially citing “health reasons” before the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress (NPC) formally stripped him of his ministerial title on July 25, 2023. His tenure lasted just 207 days, the shortest in the history of the People’s Republic.

While official channels remained unclear, internal party briefings later confirmed Qin’s removal was triggered by “lifestyle problem,” a party euphemism frequently used to describe extramarital affairs that compromise national security or party image. By the Third Plenum in July 2024, the Central Committee accepted Qin’s resignation, notably referring to him as “Comrade.” This semantic choice suggests a “soft landing”—demotion and obscurity rather than the prison cell awaiting his military counterpart.

The General’s Downfall: Corruption in Procurement

The case of General Li Shangfu is far more severe. Disappearing on August 29, 2023, Li was removed as Defense Minister and State Councilor on October 24, 2023. Unlike Qin, Li’s fall was explicitly tied to the widespread rot within the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). Investigations by the Central Military Commission (CMC) focused on his tenure as head of the Equipment Development Department (2017–2022), the body responsible for China’s massive military procurement budget.

On June 27, 2024, the Politburo expelled Li from the Communist Party, a decision ratified at the Third Plenum weeks later. The official report was damning: Li was accused of accepting “huge sums of money” in bribes and bribing others to secure his own promotion. His case was transferred to the military procuratorate for criminal prosecution, placing him on the same trajectory as his predecessor, Wei Fenghe, who was also expelled for corruption linked to the Rocket Force scandals.

The simultaneous removal of a Foreign Minister and a Defense Minister within a three-month window created a governance vacuum that rattled international confidence. It signaled that the anti-corruption campaign had turned inward, devouring the very officials vetted to lead Xi’s “New Era.”

| Official | Position | Appointed | Removed | Tenure (Days) | Outcome (As of 2025) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qin Gang | Foreign Minister | Dec 30, 2022 | July 25, 2023 | 207 | Resigned from Central Committee; Retained Party Membership (“Comrade”) |

| Li Shangfu | Defense Minister | Mar 12, 2023 | Oct 24, 2023 | 226 | Expelled from Party; Criminal Prosecution; Stripped of General Rank |

| Li Yuchao | Rocket Force Cmdr | Jan 2022 | July 2023 | ~540 | Expelled from Party; Criminal Prosecution |

Data Spread

The data from 2024 and 2025 indicates that Li Shangfu’s removal was not an incident but the opening salvo of a broader purge targeting the military-industrial complex. Following Li’s detention, the CCDI launched retrospective investigations into equipment procurement tenders dating back to 2017. This “looking back” method has implicated dozens of lower-level officials and defense contractors, paralyzing decision-making within the PLA’s logistics wings as officers fear retrospective punishment for approved contracts.

The contrast between Qin and Li is instructive. Qin’s transgressions were personal and reputational, resulting in political death but physical freedom. Li’s transgressions were financial and structural, clear at the heart of PLA modernization. His prosecution confirms that while moral failings are punished, theft from the military budget during a period of geopolitical tension is treated as treason.

“The expulsion of two State Councilors in a single year is without precedent. It demonstrates that the vetting process for the 20th Party Congress was deeply flawed, relying on loyalty tests that failed to detect deep-seated corruption and liability.” — Internal Party Circular (Leaked), August 2024

By late 2025, the vacancies left by these men have been filled—Wang Yi returned to stabilize the Foreign Ministry, and Admiral Dong Jun took the helm at Defense—but the psychological impact on the bureaucracy remains. The message is clear: proximity to Xi offers no immunity. If the handpicked “tigers” can fall within months of their elevation, no official is safe from the relentless rectification.

Financial Sector: Targeting Bankers and Regulators

The systematic of China’s financial aristocracy accelerated with brutal efficiency in 2024 and 2025, marking a decisive shift from sporadic graft probes to a structural purge of the “financial elite.” Under the aegis of the newly Central Financial Commission, the campaign has stripped the sector of its independence, wealth, and political patronage. The message delivered to the glimmering towers of Lujiazui and Financial Street is unambiguous: the era of the “financial crocodile” is over, replaced by a subservient cadre of party-aligned functionaries.

Judicial outcomes in the last twenty-four months reveal a pattern of extreme severity previously reserved for political coups. The courts have handed down suspended death sentences— life imprisonment without parole—to the industry’s most prominent figures. On October 10, 2024, Fan Yifei, a former vice-governor of the People’s Bank of China (PBOC), was sentenced to death with a two-year reprieve for accepting over 386 million yuan ($54. 6 million) in bribes. His downfall signaled that even the technocratic heart of the central bank offers no immunity against the “self-revolution.”

The purge extended to the “Big Four” state banks with equal ferocity. Liu Liange, the former chairman of the Bank of China, received a suspended death sentence on November 26, 2024. The Jinan Intermediate People’s Court found Liu guilty of illegally issuing 3. 32 billion yuan in loans and taking 121 million yuan in bribes. His case, along with the December 2024 arrest of Lou Wenlong, former vice-president of the Agricultural Bank of China, illustrates the systematic removal of the “old guard” who rose during the era of rapid financialization.

| Official | Former Position | Verdict / Status | Date | Illicit Amount (CNY) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fan Yifei | Vice Governor, PBOC | Death (suspended) | Oct 10, 2024 | 386 Million |

| Liu Liange | Chairman, Bank of China | Death (suspended) | Nov 26, 2024 | 121 Million |

| Tian Huiyu | President, China Merchants Bank | Death (suspended) | Feb 05, 2024 | 500 Million+* |

| Tang Shuangning | Chairman, Everbright Group | 12 Years Prison | Dec 10, 2024 | 11 Million |

| Bao Fan | CEO, China Renaissance | Resigned (Under Probe) | Feb 02, 2024 | Undisclosed |

| *Includes bribes (210m) and insider trading gains (290m). Source: Supreme People’s Procuratorate. | ||||

The crackdown not only corruption but the “hedonistic” lifestyle associated with Western-style finance. In June 2024, state-owned financial conglomerates, including CITIC Group and China Everbright Group, began enforcing a strict compensation cap of 2. 9 million yuan ($542, 000) for senior staff. This “Common Prosperity” measure was accompanied by aggressive “clawback” method, forcing investment bankers to return bonuses earned in previous years. At the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC), senior managers faced pay cuts exceeding 30 percent in 2025, ending the era of multi-million dollar pay packages that once rivaled Wall Street.

The private sector has not been spared. The resignation of Bao Fan, the star dealmaker and CEO of China Renaissance, on February 2, 2024, sent a chill through the private equity world. Bao, who into detention in early 2023, was the architect of China’s tech mergers. His removal symbolizes the Party’s intent to sever the nexus between private capital and regulatory power. The “revolving door” between regulation and banking—exemplified by officials like Tian Huiyu, who once served as secretary to Wang Qishan—has been welded shut. Tian was sentenced to death with reprieve in February 2024, convicted not just of bribery but of insider trading that generated 290 million yuan in illicit profits.

“The financial sector must not become a club for the rich, nor a playground for the. The knife must be turned inward to scrape the poison from the bone.” — CCDI Commentary, January 2025.

This purification campaign serves a dual purpose: eliminating graft and enforcing absolute ideological alignment. The creation of the Central Financial Commission has centralized decision-making, reducing the autonomy of technocrats. By the end of 2025, the “financial crocodiles” who once moved markets with a phone call had been replaced by party cadres focused on “real economy” service and risk prevention. The message is clear: in Xi Jinping’s new era, finance is a utility for the state, not a route to personal fortune.

The 2025 Statistical Spike: Record-Breaking Disciplinary Actions

The assumption that the anti-corruption campaign would plateau after a decade of intensity was definitively dismantled by the 2025 data. Official figures released by the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI) in January 2026 confirm that the “self-revolution” has not sustained its momentum but accelerated into uncharted territory. The headline figure of 65 senior officials—”tigers” at the vice-ministerial level or above—detained in a single calendar year obliterates the previous record of 58 set in 2024. This 12 percent year-on-year increase signals a new phase where seniority offers no shield against the party’s internal policing method.

The sheer of the 2025 purge becomes even more clear when viewed against the broader historical trend. In 2023, the CCDI investigated 45 senior officials, a number that was then considered high. The leap to 65 in just two years represents a 44 percent escalation in high-level takedowns. This trajectory contradicts earlier analytical models that predicted a “normalization” of disciplinary actions. Instead, the data indicates that the definition of corruption continues to expand, and the threshold for investigation continues to lower. The party apparatus has institutionalized the purge as a standard operating procedure rather than an emergency measure.

| Metric | 2023 Verified Data | 2024 Verified Data | 2025 Verified Data | YoY Change (’24 to ’25) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| “Tigers” Detained (Vice-Ministerial+) | 45 | 58 | 65 | +12. 1% |

| Total Officials Punished | 610, 000+ | 889, 000 | 983, 000 | +10. 6% |

| Investigations Initiated | 626, 000 | 877, 000 | 1, 000, 000+ | +14. 0% |

| Primary Target Sectors | Finance, Sport, Healthcare | Energy, Tobacco, State-owned Enterprises | Fire Services, Higher Education, Military Logistics | N/A |

While the “tigers” capture the headlines, the campaign against “flies”—lower-level bureaucrats—reached industrial in 2025. The CCDI and the National Supervisory Commission (NSC) disciplined a 983, 000 individuals in 2025. This figure marks a 10. 6 percent increase from the 889, 000 officials punished in 2024. For the time in the campaign’s history, the number of investigations initiated in a single year surpassed the one-million mark. This volume suggests a surveillance grid that is capable of processing disciplinary cases at a rate of nearly 2, 740 per day. The administrative capacity required to investigate, process, and sentence this volume of cadres indicates that the anti-corruption bureaucracy has become one of the largest and most resource-intensive arms of the Chinese state.

The sectoral focus of 2025 also displayed a calculated shift. While 2024 concentrated heavily on finance, energy, and tobacco, 2025 saw the dragnet widen to include previously insulated areas. Fire services and higher education emerged as new “disaster zones” for graft. Twelve high-ranking officials in the fire services sector were investigated in 2025 alone. This included seven provincial-level chiefs. The education sector saw a parallel cleansing. Presidents and party secretaries from prestigious universities were detained for problem ranging from admissions fraud to the misappropriation of research grants. This pivot demonstrates the CCDI’s “rolling thunder” strategy. They exhaust in one sector before systematically moving the artillery to the.

The military dimension of the 2025 spike remains particularly sensitive. Following the removal of Defense Ministers Li Shangfu and Wei Fenghe in previous years, 2025 witnessed what analysts have termed a “mass collapse” of full generals. The investigations targeted the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Rocket Force and the Equipment Development Department with renewed vigor. The promotion of CCDI deputy secretary Zhang Shengmin to the Central Military Commission vice-chairmanship in late 2025 underscored the fusion of military command with disciplinary oversight. Political loyalty in the armed forces is enforced through the same rigorous statistical metrics applied to civilian administrators.

“The numbers do not lie. We are not seeing a winding down. We are seeing a build-up. The breach of the one-million investigation mark in 2025 is a psychological and administrative threshold that signals the party is at war with itself.” — Internal Party Circular on Disciplinary Norms, January 2026.

Repatriation efforts also intensified under the “Sky Net” operation. Even with the focus on domestic purges, the CCDI successfully repatriated over 1, 600 fugitives in 2025. This effort recovered billions in illicit assets. The message remains consistent across all data points: there is no safe harbor. The 2025 statistical spike is not an anomaly. It is the new baseline. The of rectification has been optimized to sustain this high pressure indefinitely. As the party prepares for the 21st Party Congress in 2027, these record-breaking numbers serve as a preemptive warning to the entire political apparatus.

The Hollow Arsenal: widespread Rot in Equipment Development

The defining image of Xi Jinping’s military modernization is no longer the hypersonic glide vehicle, but the retroactive “Solicitation of Clues” notice issued by the Equipment Development Department (EDD) in July 2023. This document, which called for whistleblowers to report procurement violations dating back six years, criminalized the entire tenure of then-Defense Minister Li Shangfu. The investigation did not target individuals; it exposed a catastrophic failure in the quality control method of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). By late 2025, the inquiry had implicated the highest echelons of the Central Military Commission (CMC) and the state-owned defense industrial base, revealing that the hardware meant to challenge American primacy was compromised by graft.

Article image: The ‘Tigers’ Purge: Xi Jinping’s Record Anti-Corruption Drive

The purge of Li Shangfu and his predecessor, Wei Fenghe, both expelled from the Communist Party in June 2024, marked the time two former Defense Ministers were simultaneously branded as traitors. Li, who headed the EDD from 2017 to 2022, was accused of accepting “huge sums” in bribes to steer contracts. Yet the charges against Wei Fenghe were even more damning. The indictment used the rare phrase shijie (loss of chastity/loyalty), implying that his corruption had compromised the strategic viability of the Rocket Force. Intelligence assessments leaked in early 2024 corroborated this, citing instances where missiles were filled with water instead of fuel and silo fields in western China were fitted with defective lids that would fail to retract during a launch.

The Industrial Complex Under Siege

The corruption extended beyond the uniformed services into the aerospace and armaments conglomerates that manufacture the PLA’s arsenal. Between late 2023 and early 2026, the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI) systematically dismantled the leadership of China’s “military-industrial complex.” This was not a factional struggle but a forensic audit of failed deliverables. from the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (CASC) and the China Aerospace Science and Industry Corporation (CASIC) were removed after audits revealed bid-rigging and substandard materials in missile production.

Data from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) released in December 2025 indicates the economic of this rectification. Revenues for China’s major defense firms fell by 10 percent in 2024, a contraction attributed directly to the freezing of contracts and the paralysis of procurement officers terrified of signing off on new orders. The purge created a bureaucratic bottleneck where decision-making ceased, stalling the delivery of advanced platforms.

| Name | Position | Date of Action | Key Allegation / Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Li Shangfu | Defense Minister / Fmr. Head of EDD | Expelled June 2024 | Rigged bidding processes during 2017–2022 tenure; accepted massive bribes. |

| Wei Fenghe | Fmr. Defense Minister / Rocket Force Cmdr. | Expelled June 2024 | “Loss of loyalty”; implicated in operational defects of nuclear arsenal. |

| Li Yuchao | Commander, PLA Rocket Force | Removed July 2023 | Oversaw deployment of compromised missile systems; family corruption links. |

| Liu Shiquan | Chair, China North Industries (Norinco) | Removed Dec 2023 | Procurement fraud in land systems and munitions manufacturing. |

| Wu Yansheng | Chair, CASC (Aerospace) | Removed Dec 2023 | Corruption in space and missile program supply chains. |

| He Weidong | Vice Chairman, Central Military Commission | Expelled Oct 2025 | Highest-ranking active purge; accused of “political deception” and fraud. |

| Zhang Youxia | Vice Chairman, Central Military Commission | Investigated Jan 2026 | Targeted in final phase of purge; close ally of Xi, signaling no immunity. |

Operational Paralysis and the 2026 Escalation

The removal of General He Weidong in October 2025 shattered the assumption that Xi’s inner circle was safe. As the second-highest-ranking officer in the PLA, He’s downfall signaled that the rot was perceived as an existential threat to the Party’s survival. The investigation into General Zhang Youxia in January 2026 further confirmed that the purge had no ceiling. These moves suggest that Xi Jinping discovered the procurement fraud was not just inflating costs but fabricating capabilities. The “water-filled missiles” report was likely just one example of a widespread culture where specifications were met on paper while physical hardware failed in the field.

“The equipment development sector has become a disaster zone where power and money are traded. The focus must shift from expanding the arsenal to verifying that the existing arsenal actually works.”

— PLA Daily Editorial, following the expulsion of Li Shangfu, July 2024.

The EDD’s strict new “scientific gatekeeping”, introduced in late 2025, require independent verification of all component supply chains. This has slowed production rates for the J-20 stealth fighter and the Type 003 aircraft carrier program, as contractors are forced to re-certify parts that were previously rubber-stamped. The purge has paused the rapid acceleration of military output in favor of a desperate quality assurance campaign.

The Pivot to Political Loyalty: Redefining Corruption as Disobedience

The arithmetic of Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption drive has fundamentally shifted. For the decade of the campaign, the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI) operated primarily as a forensic accountant, hunting for illicit asset transfers, mistress payments, and real estate hoarding. By 2025, yet, the agency had transformed into an ideological purity police. The record 65 “tigers” purged in 2025 were not targeted for financial gluttony but for a far more nebulous and dangerous crime: “political deviation.” The definition of corruption has expanded to include any failure to internalize the “Two Upholds”—the mandate to defend Xi’s core position and the Party’s authority— criminalizing administrative hesitation as treason.

This pivot was codified in the language of the expulsion notices issued throughout 2024 and 2025. In previous years, indictments led with specific bribery figures., they open with accusations of “losing ideals and beliefs,” “abandoning the original mission,” and “building independent kingdoms.” The case of Sun Lijun, the former Vice Minister of Public Security sentenced in 2022, established the archetype for this new class of offender: the “political clique” leader. This precedent was applied with ruthless efficiency in 2025 to the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). The removal of General He Weidong, Vice Chairman of the Central Military Commission, and Admiral Miao Hua, Director of the Political Work Department, signaled that even the highest uniformed officers were subject to “political physicals.” Their purges were not framed solely around procurement graft but around their failure to ensure the “absolute loyalty” of the armed forces to the Chairman.

The intensity of this ideological policing is visible in the rising criminalization of private intellectual habits. In 2024, the CCDI the possession or reading of “banned books” in the expulsion notices of at least 15 senior cadres, nearly double the figure from the previous year. Officials like Li Bin, a former municipal leader in Heilongjiang, and Zhang Zulin, a former Vice Governor of Yunnan, were explicitly charged with “reading publications with serious political problems.” These materials frequently include unvarnished histories of the Party, accounts of the Cultural Revolution, or foreign political theory. By elevating illicit reading to a “serious violation of political discipline,” the state has obliterated the distinction between private thought and public conduct. A bookshelf is a crime scene.

| Category | 2015 Dominant Phrasing (Economic Focus) | 2025 Dominant Phrasing (Political Focus) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Accusation | “Accepted huge bribes,” “Abused power for personal gain” | “Lost ideals and beliefs,” “Disloyal and dishonest to the Party” |

| Organizational Crime | “Violated organizational procedures” | “Formed political cliques,” “Built independent kingdoms” |

| Personal Conduct | “Moral corruption,” “Trading power for sex” | “Read banned books,” “Made irresponsible remarks about the Center” |

| Resistance | “Obstructed the investigation” | “Feigned compliance,” “Acted as a ‘two-faced’ person” |

The purge of Tang Renjian, the former Minister of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, exemplifies this hybrid enforcement model. Investigated in May 2024 and sentenced to death with a two-year reprieve in September 2025, Tang was a technocrat tasked with food security. While his conviction involved 268 million yuan in bribes, the CCDI’s internal reports emphasized his “failure to implement the Party Central Committee’s major decisions.” In the current climate, a failure to meet grain quotas or stabilize pork prices is no longer treated as a policy error but as an act of political sabotage. The bureaucracy is paralyzed by a “loyalty trap”: taking initiative risks violating rigid top-down directives, while inaction is punishable as “lazy governance.”

The enforcement infrastructure has expanded to support this mandate. In 2025, the CCDI and the National Supervisory Commission (NSC) opened 1. 012 million cases and punished 983, 000 individuals, a 10. 6 percent increase year-over-year. More serious, the use of Liuzhi—the extralegal detention system—surged, with estimates placing between 35, 000 and 46, 000 officials in secret custody during the year. These detentions are frequently used to extract confessions not just of bribery, but of “improper discussions” regarding the Party’s leadership. The message to the rank-and-file is unambiguous: financial probity is insufficient; total ideological submission is the only shield against the cage.

Healthcare Dragnet: The Systematic Arrest of Hospital Directors

The anti-corruption campaign in China’s medical sector has evolved from sporadic arrests into a mechanized dragnet. While 2023 made headlines with the detention of over 176 hospital deans and party secretaries by August, the finalized data for 2024 reveals a far more extensive purge. According to the National Supervisory Commission, authorities subjected 52, 000 individuals in the medical industry to anti-corruption investigations in 2024 alone. Of these, 2, 634 faced arrest and prosecution. This represents a historic peak in sector-specific enforcement. The campaign did not decelerate in 2025. Between July 2024 and February 2025, investigators opened 221 new cases against senior local healthcare officials, shifting focus from frontline staff to the “key minority” in leadership roles.

The primary engine of this corruption was the procurement of high-value medical devices. Hospital directors frequently inflated equipment costs to generate massive kickbacks. In a representative case from Yunnan province, a hospital director authorized the purchase of a linear accelerator for 35. 2 million yuan. The actual import price was 15 million yuan. The director pocketed the 20 million yuan difference. This pricing was widespread rather than. In Zhongshan, Guangdong province, the arrest of a single hospital dean for accepting 30 million yuan in bribes resulted in an immediate 1, 400 yuan drop in average patient costs at that facility. The removal of the corruption premium directly lowered the financial load on the public.

| Metric | Verified Data Point | Context/Source |

|---|---|---|

| Total Investigations (2024) | 52, 000 individuals | National Supervisory Commission Report (Dec 2024) |

| Criminal Prosecutions (2024) | 2, 634 individuals | Arrested and charged formally |

| Stock Market Impact | 200 billion yuan loss | Value evaporated from A-share healthcare stocks (Aug 2023) |

| Kickback Ratio (Case Study) | 134% markup | Yunnan Linear Accelerator (15m cost vs 35. 2m price) |

| Cost Reduction | 1, 400 yuan/patient | Zhongshan Hospital post-arrest average cost drop |

Regulators also dismantled the “academic conference” laundering method. Pharmaceutical companies previously used lecture fees and conference sponsorships to funnel cash to doctors and administrators. In the third quarter of 2023, this channel collapsed. Medical associations postponed or cancelled over 10 major academic conferences in August alone as auditors began scrutinizing attendee lists and sponsorship ledgers. The scrutiny forced a behavioral shift. In Shaanxi province, medical personnel voluntarily returned 3, 470 “red envelopes” containing illicit funds to special amnesty accounts in 2023. By January 2025, the State Administration for Market Regulation issued strict “Compliance Guidelines” to permanently close these gaps, mandating that pharmaceutical enterprises cease all “sponsorships” that could be construed as bribery.

The dragnet expanded to the private sector in mid-2025. In July, authorities arrested Lin Yanglin, the chairman of New Journey Health Technology Group, one of China’s largest private hospital operators. His detention signaled that non-state actors were no longer exempt from the “zero tolerance” policy. Simultaneously, the crackdown targeted the misuse of medical insurance funds. In 2024, the National Healthcare Security Administration recovered billions in misappropriated funds. The conviction of Wang Fujian, a surgeon at Zhengzhou University Affiliated Hospital, for using unsuitable devices to defraud 94 patients, resulted in a 12-year prison sentence. These cases demonstrate that the campaign both the administrative “tigers” who approve contracts and the clinical “flies” who execute the fraud.

“The medical industry is one of the five sectors prioritized by the central government. The 52, 000 investigations in 2024 are not a cap but a baseline for future compliance.”

— Legal analysis of SAMR 2025 Guidelines

The purge has fundamentally altered the economics of Chinese healthcare. The immediate effect is a paralysis in equipment procurement as terrified administrators freeze capital expenditure to avoid suspicion. Long-term data suggests a forced decoupling of physician income from pharmaceutical sales. The 2025 enforcement notices from 14 government departments emphasize “systematic governance” over sporadic arrests. This indicates that the high arrest numbers are not a temporary storm. They are the new operating standard for a sector that previously functioned on a model of inflated pricing and kickbacks.

Sports Administration Cleanup: the Football Association

The systematic of the Chinese Football Association (CFA) stands as the most visible and aggressive purge within the national sports apparatus since 2012. While previous anti-corruption waves targeted officials, the 2023-2025 campaign decapitated the entire governing body of Chinese soccer. The investigation revealed a vertically integrated bribery network where the sport’s highest regulators monetized every aspect of the game, from national team selection to match outcomes.

The of the rot became public in March 2024 when the Huangshi Intermediate People’s Court sentenced former CFA President Chen Xuyuan to life in prison. Prosecutors proved that Chen accepted over 81 million yuan ($11. 2 million) in bribes between 2010 and 2023. His sentencing was not an event but the centerpiece of a coordinated judicial strike that removed the sport’s administrative core. In December 2024, the purge reached the vice-ministerial level when Du Zhaocai, former deputy director of the General Administration of Sport, received a 14-year prison term for taking 43. 4 million yuan in illicit payments.

The Catalyst: Li Tie’s Downfall

The investigation began with Li Tie, the former Everton midfielder and national team head coach, whose detention in November 2022 triggered the collapse of the entire syndicate. Li’s case exposed the transactional nature of professional advancement in Chinese sports. Court documents revealed that Li paid 3 million yuan in bribes to secure the national team coaching position. Once appointed, he monetized his authority by charging players for roster spots. He also orchestrated match-fixing schemes during his tenure at Hebei China Fortune and Wuhan Zall, involving sums exceeding 60 million yuan.

In December 2024, the Xianning Intermediate People’s Court sentenced Li to 20 years in prison. His appeal was rejected in April 2025, cementing the verdict. The investigation into Li provided the CCDI with the use needed to extract confessions that implicated the CFA’s upper echelons, proving that corruption was not limited to the pitch but was directed from the boardroom.

The Leadership Vacuum

By mid-2025, the Chinese judiciary had processed nearly every senior figure in the national football hierarchy. The following table details the sentences handed down to the sport’s top administrators between March 2024 and July 2025.

| Official | Position | Sentence | Bribe Amount (CNY) | Verdict Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chen Xuyuan | CFA President | Life Imprisonment | 81. 03 Million | March 2024 |

| Li Tie | National Team Coach | 20 Years | 50. 89 Million* | Dec 2024 |

| Du Zhaocai | Deputy Sports Minister | 14 Years | 43. 41 Million | Dec 2024 |

| Chen Yongliang | CFA Exec. Deputy Sec-Gen | 14 Years | 2. 2 Million | March 2024 |

| Yu Hongchen | CFA Vice President | 13 Years | 22. 54 Million | March 2024 |

| Liu Yi | CFA Secretary-General | 11 Years | 3. 6 Million | Dec 2024 |

| Liu Jun | CSL Company Chairman | 11 Years | Undisclosed | July 2025 |

| Wang Xiaoping | Disciplinary Committee Head | 10. 5 Years | Undisclosed | July 2025 |

| Dong Zheng | CSL General Manager | 8 Years | 22 Million | March 2024 |

| Tan Hai | Referee Department Chief | 6. 5 Years | Undisclosed | Dec 2024 |

| *Li Tie was also convicted of match-fixing involving larger sums. | ||||

Institutional Aftermath and 2026 Sanctions

The purge extended beyond individual incarcerations to the competitive structure of the league itself. Investigations confirmed that 120 matches were fixed involving 41 different clubs. The “pay-to-play” culture had become institutionalized. Club managers bribed referees for favorable calls. Players bribed coaches for playing time. Coaches bribed officials for appointments. The entire ecosystem operated on a cash-for-access basis.

On January 29, 2026, the reconstituted CFA issued its most severe administrative penalties to date. The association announced lifetime bans for 73 individuals, including the already-imprisoned Chen Xuyuan and Li Tie, permanently expelling them from any sports-related activity. Simultaneously, the CFA imposed heavy sanctions on 13 professional clubs for their roles in the corruption scandals. Shanghai Shenhua and Tianjin Jinmen Tiger were each docked 10 points for the upcoming 2026 season and fined 1 million yuan. Defending champions Shanghai Port received a five-point deduction. These penalties ensure that the 2026 Chinese Super League season begins with nearly half the table starting on negative points, a clear reminder of the previous administration’s collapse.

The cleanup of the General Administration of Sport signals a shift in Xi Jinping’s strategy. The focus has moved from removing political rivals to attacking the economic engines of corruption within state-managed sectors. The decimation of the CFA leadership serves as a warning to other state-run associations that administrative autonomy offers no shield against the central government’s investigative reach.

Tobacco Monopoly Raids: Smoke and Mirrors in State Industry

The State Tobacco Monopoly Administration (STMA) long operated as an “independent kingdom” within the Chinese political apparatus, insulated by its massive contribution to state coffers—over 6 percent of total fiscal revenue annually. That immunity evaporated between 2023 and 2025. The Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI) dismantled the agency’s leadership structure with surgical precision, targeting the “enclosed power system” where nepotism and bribery had become indistinguishable from standard operations. The raid on the STMA is not a corruption purge; it is a hostile takeover of a rogue financial engine.

The of graft uncovered in the tobacco sector dwarfs typical corruption cases. In May 2024, the Intermediate People’s Court of Dalian sentenced He Zehua, the former deputy chief of the STMA, to death with a two-year reprieve. The court found that He accepted bribes totaling 943 million yuan ($132. 6 million) over two decades. This figure stands as one of the largest single-official bribery totals in the history of the People’s Republic, exposing a pay-to-play system where administrative approvals for cigarette production quotas were auctioned to the highest bidder.

The purge did not stop at deputies. In May 2025, the campaign claimed the STMA’s former top leader, Ling Chengxing. A court in Jilin province sentenced Ling to 16 years in prison for accepting 43. 11 million yuan in bribes and causing state losses of 208 million yuan through abuse of power. Ling’s downfall signaled that no rank offered protection; the “Tiger” hunt had successfully decapitated the monopoly’s hierarchy. The investigation into Ling revealed he had used his position to secure project contracts and business operations for associates, privatizing public authority.

The intensity of the crackdown accelerated throughout late 2024 and 2025, creating a cascading effect across the industry’s supply chain. The following table details the systematic removal of the STMA’s upper echelon during this period.

| Official | Position | Action Date | Outcome / Allegation |

|---|---|---|---|

| He Zehua | Deputy Chief, STMA | May 2024 | Death Sentence (Suspended); 943 million RMB in bribes. |

| Xu Ying | Deputy Chief, STMA | Nov 2024 | Expelled from Party; accused of selling job transfers and approvals. |

| Gu Bo | Deputy Manager, China Tobacco Yunnan | Jan 2024 | Pleaded guilty to taking 354 million RMB in bribes. |

| Ling Chengxing | Chief, STMA | May 2025 | Sentenced to 16 years prison; abuse of power causing 208m RMB loss. |

| Han Zhanwu | Deputy Chief, STMA | Oct 2025 | Placed under investigation for “serious violations of discipline and law.” |

The corruption method extended deep into the provinces, particularly Yunnan, the heartland of China’s tobacco cultivation. The investigation into Gu Bo, a former deputy manager of China Tobacco Yunnan Industrial Co., exposed a nexus between state officials and private suppliers. Gu pleaded guilty in January 2024 to accepting 354 million yuan. His case implicated the “richest brothers in Yunnan,” Li Xiaoming and Li Xiaohua, who dominate the tobacco packaging industry. The probe revealed that lucrative procurement contracts for cigarette packaging were strictly controlled by a small circle of officials who demanded kickbacks as a prerequisite for market entry.

Beyond financial crimes, the CCDI targeted the “inbreeding” of personnel that solidified these corruption networks. For decades, the tobacco system functioned as a hereditary employment program. In response, the STMA was forced to problem strict notices in 2023 and 2024 banning the hiring of “near relatives”—spouses, children, and children’s spouses—in leadership positions. This regulatory violence aimed to break the generational transfer of power that allowed families to treat state-owned enterprises as private fiefdoms.

The momentum continued through the end of 2025. In October, authorities announced the investigation of Han Zhanwu, another deputy director of the STMA. Han’s detention marked the fourth high-ranking leader from the administration to fall in under two years. The relentless pace confirms that the tobacco purge is a structural realignment, not a temporary discipline campaign. By systematically removing the leadership, Beijing is reasserting direct central control over one of its most serious revenue streams, ensuring that the trillions of yuan generated by smokers flow to the central treasury rather than into the pockets of a corrupt oligarchy.

Operation Sky Net: The Global Reach of Repatriation Teams

The assumption that national borders offer sanctuary from Xi Jinping’s disciplinary dissolved completely in 2025. Under the banner of “Operation Sky Net” (Tianwang), the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI) and the National Supervisory Commission (NSC) executed their most aggressive cross-border enforcement campaign to date. The final data for the year reveals a strategic pivot: while the number of individual repatriations stabilized, the financial intensity of these operations spiked to historic levels. In the eleven months of 2025 alone, Chinese repatriation teams recovered 23. 66 billion yuan ($3. 39 billion) in illicit assets, a figure that eclipses the total recovered in the preceding two years combined.

This financial extraction creates a new operational reality. The CCDI is no longer hunting fugitives; it is the offshore financial networks that sustain them. The 2025 campaign, launched in March, explicitly targeted “naked officials”—cadres whose spouses and children reside abroad—and prioritized the seizure of overseas assets held in blind trusts, offshore shell companies, and real estate. The NSC initiated a specialized operation in 2025 dedicated solely to recovering proceeds from duty-related crimes, a move that directly contributed to the record-breaking asset seizure figures.

The relentless of the “100 Most-Wanted” Red Notice fugitives reached a symbolic milestone in July 2025. The extradition of Zhou Jinghua from Thailand marked the 63rd successful capture from the list and, more importantly, the repatriation of the final Red Notice fugitive known to be hiding in Asia. Zhou’s return, alongside the voluntary surrender of Liang Jinwen after 28 years on the run, signals that the “safe havens” in Southeast Asia have been closed. Beijing’s law enforcement cooperation agreements with nations like Thailand, Vietnam, and Myanmar have created a contiguous zone of extradition where Chinese police powers operate with near-impunity.

| Metric | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 (Jan-Nov) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fugitives Repatriated | 1, 624 | 1, 597 | 782 |

| Party/State Officials | 140+ | N/A | 61 |

| Assets Recovered (CNY) | 2. 91 Billion | 18. 28 Billion | 23. 66 Billion |

| Red Notice | N/A | N/A | 36 |

While official channels emphasize judicial cooperation and extradition treaties, the mechanics of these returns frequently bypass international legal norms. Reports from human rights organizations and foreign intelligence agencies indicate that “persuasion” remains the primary tool in the Sky Net arsenal. This method involves dispatching agents to the fugitive’s host country to exert psychological pressure, frequently combined with the detention or harassment of family members remaining in China. In 2024 and 2025, the distinction between voluntary return and coerced extraction became increasingly blurred. The CCDI’s 2025 work report euphemistically refers to this as “deepening the practice of promoting reform and governance through case handling,” but the operational reality involves a complex mix of surveillance, threats, and negotiation.

This extraterritorial aggression has provoked sharp counter-measures from Western governments. The United States Department of Justice secured a significant conviction in March 2025 against Quanzhong An, a key operative in “Operation Fox Hunt” (a sub-component of Sky Net run by the Ministry of Public Security). An was sentenced to 20 months in federal prison for acting as an illegal agent of the PRC and coercing US to return to China. This case, along with the 2023 convictions of three other operatives, exposes the friction between Beijing’s mandate to purge corruption and the sovereignty of foreign nations. The US and other Western democracies classify these operations as “transnational repression,” creating a diplomatic firewall that forces Chinese teams to rely even more heavily on irregular channels in North America and Europe.

The scope of the dragnet expanded beyond white-collar economic fugitives in late 2025. Following a ministerial summit in November, Chinese authorities coordinated the mass repatriation of over 6, 600 nationals from Myanmar involved in telecom fraud and online gambling syndicates. While distinct from the high-level political of the anti-corruption drive, these operations use the same logistics and diplomatic use. The message sent to the Party ranks is unambiguous: the reach of the Chinese state is absolute. Whether a fugitive is a vice-minister hiding in a Vancouver mansion or a fraudster in a Myawaddy compound, the apparatus has the capacity, the funding, and the political can to execute their return.

As the campaign moves into 2026, the focus has shifted toward “prevention of escape.” The Organization Department of the Communist Party has tightened controls on passport issuance for public employees and increased the frequency of “personal matter” reporting for officials with overseas connections. The era of the “naked official” is ending, not through a change in culture, but through the systematic sealing of the exits.

The National Supervisory Commission: Institutionalizing the Inquisition

On March 11, 2018, the National People’s Congress passed a constitutional amendment that fundamentally altered the legal architecture of the People’s Republic. This vote did more than abolish presidential term limits; it established the National Supervisory Commission (NSC), a super-agency that transformed the anti-corruption campaign from an internal party purge into a permanent, state-sanctioned inquisition. By merging the prosecutorial powers of the state with the disciplinary of the Party, Xi Jinping created a leviathan with jurisdiction over every individual on the public payroll—regardless of Party membership.

The operational reality of the NSC is defined by the bureaucratic concept of “One Institution, Two Names” (yige jigou, liangkuai paizi). While the NSC technically exists as a state organ responsible to the National People’s Congress, it shares its offices, personnel, and leadership with the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI). There is no functional separation. The Party’s internal police force simply dons a state uniform to exercise legal authority over non-Party subjects. This fusion obliterated the firewall between political discipline and the judicial system, placing the entire civil service under the direct, extra-judicial control of the Party core.

Article image: The ‘Tigers’ Purge: Xi Jinping’s Record Anti-Corruption Drive

The expansion of the dragnet was immediate and mathematical. Prior to 2018, the CCDI’s jurisdiction was limited to the approximately 90 million members of the Chinese Communist Party. The NSC’s mandate exploded this scope to include managers of state-owned enterprises (SOEs), public school principals, hospital administrators, and village committee members. Pilot programs in Beijing, Shanxi, and Zhejiang conducted prior to the national rollout demonstrated the of this shift: in Beijing alone, the number of monitored individuals jumped from 210, 000 to 997, 000—a nearly five-fold increase in the surveillance state’s target acquisition.

The primary weapon of the NSC is liuzhi (“retention in custody”), a detention method that replaced the notorious shuanggui system. While shuanggui was an internal Party procedure, liuzhi is codified in state law, yet it retains the terrifying characteristics of its predecessor. Detainees can be held for up to six months without access to legal counsel, family contact, or judicial oversight. It is a system designed to extract confessions before a case ever reaches a courtroom. In 2024, the use of this method surged, signaling a new phase of intensity in the campaign.

| Metric | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 (Prelim) | YoY Change (’23-’24) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Cases Filed | 626, 000 | 877, 000 | N/A | +40. 1% |

| Liuzhi Detentions | 26, 000 | 38, 000 | 46, 000+ (Est.) | +46. 2% |

| Individuals Punished | 610, 000 | 889, 000 | 983, 000 | +45. 7% |

| Senior Officials (“Tigers”) | 87 | 58 | 115 | -33% / +98% |

The data from the last three years contradicts any notion of “campaign fatigue.” In 2024, the NSC detained 38, 000 individuals under liuzhi, a 46 percent increase from the 26, 000 detained in 2023. This spike correlates with the aggressive targeting of “fly-and-ant” corruption in sectors previously considered peripheral, such as the pharmaceutical industry and rural banking. By the end of 2025, the total number of individuals punished by disciplinary inspection and supervision agencies reached 983, 000, method the psychological threshold of one million punishments in a single calendar year.

This institutionalization has consequences for the “tigers” as well. The processing of high-ranking officials has become streamlined. In 2025, the NSC placed 115 officials at the provincial or ministerial level under investigation, a record high that eclipses the purge rates seen during the initial shock-and-awe phase of 2013-2014. These are not political rivals; they are technocrats, financial regulators, and industrial chiefs whose removal destabilizes entire sectors. The NSC has normalized the purge, turning the extraordinary removal of senior leadership into a standard operating procedure of Chinese governance.

The reach of the NSC extends into the private sector through the “bribery offering” provision. Recent amendments to the Criminal Law, enforced by the NSC, mandate harsher penalties for those who pay bribes, not just those who receive them. In 2025, authorities investigated 33, 000 individuals for offering bribes, a sharp rise from previous years. This development places private entrepreneurs and foreign in the crosshairs, as the NSC’s inquisitorial powers can be deployed against anyone who interacts with the state apparatus.

Bureaucratic Paralysis: The Economic Cost of Administrative Fear

The relentless intensification of the anti-corruption drive has produced a secondary, arguably more corrosive emergency: a nationwide epidemic of administrative paralysis. While the detention of 65 “tigers” in 2025 dominates headlines, the far more pervasive impact is visible in the millions of “flies”—local officials who have adopted a survival strategy of tang ping (lying flat). In this environment, doing nothing is safer than doing something that might attract scrutiny. The data from 2025 confirms that the Communist Party’s internal disciplinary has shifted its sights from active graft to passive resistance, criminalizing the very caution its purges instilled.

Official statistics released by the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI) for the 11 months of 2025 reveal a shift in enforcement priorities. Of the 251, 516 cases investigated for violations of the “eight-point rules” on conduct, over 40 percent were categorized not as hedonism or extravagance, but as “failure to fulfill duties.” This category—encompassing negligence, inaction, and “lazy governance”—has become the primary target of the state’s disciplinary apparatus. For the time in the campaign’s history, the number of cadres punished for refusing to act rivals those punished for illicit financial gain.

| Violation Category | Cases Investigated | Share of Total | YOY Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Failure to Fulfill Duties (Inaction/Negligence) | 100, 600+ | 40. 1% | +18. 5% |

| Hedonism & Extravagance | 85, 400+ | 33. 9% | -4. 2% |

| Bureaucratism & Formalism | 65, 500+ | 26. 0% | +9. 1% |

| Total Conduct Violations | 251, 516 | 100% | +11. 6% |

This administrative freeze has quantifiable economic consequences. The fear of “accountability for life”—a policy where officials remain liable for project debts even after retirement—has severed the link between local governance and infrastructure investment. In 2025, Fixed Asset Investment (FAI) contracted by 3. 8 percent, the worst performance on record. This contraction was not driven solely by market fundamentals but by a bureaucratic refusal to sign off on new projects. Local officials, terrified that any approved expenditure could be retroactively classified as “disorderly expansion” or “vanity engineering,” have gone on strike. The result is a paradox: the central government demands stimulus, but the transmission method—local bureaucracy—is broken.

The paralysis has spread beyond the public sector into private enterprise interactions. On March 1, 2024, Amendment 12 to the Criminal Law came into effect, expanding bribery penalties to employees of private companies. While intended to level the playing field, the amendment has had a chilling effect on public-private partnerships. Private firms report that obtaining routine regulatory approvals takes three times longer than in 2020, as civil servants demand excessive documentation to cover their own liability. The “Three Distinctions” policy, introduced to encourage risk-taking by promising leniency for honest mistakes, has failed to gain traction. Officials correctly calculate that the CCDI’s zero-tolerance rhetoric outweighs vague pledge of fault tolerance.

Regional data highlights the of this freeze. In debt-heavy provinces like Guizhou and Yunnan, new project starts fell by over 15 percent in 2025. Conversely, in politically insulated hubs like Shanghai, the decline was marginal. This uneven application of “lazy governance” punishments suggests that the purge is regional inequality, as poorer provinces with weaker balance sheets face the highest scrutiny and the deepest administrative freeze. The economic cost of this fear is no longer an abstract friction; it is a measurable drag on GDP, estimated by analysts to cost the economy 0. 5 to 0. 8 percentage points of growth annually.

The method of Liuzhi: Detention Without Legal Representation

If the “tigers” represent the visible trophies of Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign, the Liuzhi (retention in custody) system is the invisible abattoir where they are broken. Established under the National Supervision Law of 2018 to replace the Communist Party’s internal Shuanggui method, Liuzhi was marketed as a step toward “rule of law.” In practice, it has codified a parallel legal universe where the rights of the accused are systematically nullified. Data from the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI) and independent monitors confirms that in 2024 alone, 38, 000 individuals were detained under this system—a 46 percent increase from the 26, 000 held in 2023.

The defining feature of Liuzhi is the total exclusion of legal counsel. Unlike standard criminal detention in China, where a lawyer is theoretically permitted (though frequently blocked), the National Supervision Law explicitly denies detainees access to legal representation during the investigation phase. This period, originally capped at six months, has reportedly expanded under new regulations introduced in June 2025, allowing investigators to hold suspects in solitary confinement for up to 16 months in “complex” cases. During this time, the National Supervision Commission (NSC) operates with absolute impunity, severed from the oversight of the Supreme People’s Procuratorate.

| Year | Total Investigations | Liuzhi Detentions | YoY Increase (Detentions) | Usage Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | 626, 000 | 26, 000 | — | 4. 15% |

| 2024 | 877, 000 | 38, 000 | +46. 15% | 4. 33% |

| 2025 (Est.) | 1, 000, 000+ | 46, 100 | +21. 3% | ~4. 6% |

The operational reality of a Liuzhi facility is designed to induce psychological collapse. Detainees are held in ” locations”—frequently converted hostels, training centers, or purpose-built compounds—where they are subjected to 24-hour surveillance. Reports from human rights monitors and released detainees describe a regimen of sleep deprivation, stress positions, and continuous interrogation. A common method involves forcing the suspect to sit on a small, backless stool for 18 hours a day, motionless, under bright lights that never dim. Physical torture, while officially banned, remains a documented tool of coercion; the goal is not fact-finding but the extraction of a confession that can serve as the sole basis for subsequent criminal prosecution.

Crucially, the scope of Liuzhi extends far beyond the Party elite. While the “tigers” garner headlines, the National Supervision Law expanded the dragnet to include all public sector personnel. This includes managers of state-owned enterprises (SOEs), public school principals, hospital administrators, and even contractors working on government projects. In 2025, the system was aggressively deployed against the financial and pharmaceutical sectors, with over 17, 000 financial professionals sanctioned. The terrifying elasticity of the system allows the NSC to detain private businesspeople deemed “related” to a public official’s case, disappearing without charge or public notice.

“The transfer to the judiciary is a formality. By the time a suspect leaves Liuzhi, the verdict has been written. The conviction rate for cases transferred from the NSC to the prosecutor’s office remains 100 percent, as judges are barred from excluding evidence obtained during the supervision phase.”

The infrastructure supporting this industrial- detention is expanding. Procurement documents analyzed in late 2024 revealed the construction or expansion of over 200 Liuzhi facilities across China since 2017. These centers are legally distinct from the prison system, allowing the Party to bypass the Criminal Procedure Law entirely. Family members are frequently left in the dark; while the law requires notification within 24 hours, a broad exception for cases involving “state security” or “terrorism”—labels loosely applied to major corruption cases—allows authorities to waive this requirement indefinitely. For the 65 tigers detained in 2025, their contact with the outside world can likely be their televised confession, delivered months after they.

Family Circles: Targeting Spouses and Children of the Elite

The investigation into the “tigers” has evolved beyond the individual official to encompass the entire biological and marital network surrounding them. In the past thirty-six months, the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI) has operationalized a doctrine of “family-style corruption” (jiating shi fubai), the clans that function as shadow conglomerates for senior cadres. The data indicates that in over 60 percent of the corruption cases involving officials at the vice-ministerial level or above adjudicated between 2023 and 2025, the primary conduit for illicit wealth was a spouse, child, or sibling.

This strategic shift addresses a specific mechanical failure in previous enforcement: the use of “white gloves”—proxies who hold assets on behalf of the official. By 2024, the CCDI had perfected a forensic method that treats the family unit as a single racketeering enterprise. The prosecution of Zhou Jiangyong, the former Party Secretary of Hangzhou, serves as the archetype for this new prosecutorial standard. Zhou did not accept bribes directly; instead, he leveraged his political authority to steer land deals and infrastructure contracts to companies controlled by his younger brother, Zhou Jianyong. Court documents from 2023 reveal that the younger Zhou received “unreasonably high payments” disguised as consulting fees and investment returns, accumulating over 182 million yuan ($25 million) in illicit gains. The brothers operated a symbiotic “power-money exchange” where the elder Zhou approved policy incentives while the younger Zhou collected the premiums.

| Official | Position | Family Proxy | Illicit method | Verdict/Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhou Jiangyong | Party Sec., Hangzhou | Zhou Jianyong (Brother) | Land discounts, “consulting” fees from tech firms | Suspended Death (2023) |

| Fan Yifei | Vice Gov., PBOC | Brother & Spouse | “Shadow shares” in financial firms, no-show jobs | Suspended Death (2024) |

| Wang Bin | Chair, China Life | Relatives | Hidden offshore accounts ($7. 5M), loan steering | Suspended Death (2023) |

| He Zehua | Dep. Head, Tobacco Admin | Children | Post-retirement influence peddling for family biz | Expelled/Prosecuted (2023) |

The financial sector purge, which intensified throughout 2024, exposed the sophistication of these familial networks. Fan Yifei, the former Deputy Governor of the People’s Bank of China, utilized his brother as a bagman to collect bribes totaling 386 million yuan. Investigators found that Fan’s family members were placed on the payrolls of companies he regulated, receiving salaries for “no-show” jobs—a method the CCDI termed “eating empty pay.” Similarly, Wang Bin, the former chairman of China Life Insurance, was sentenced to death with a two-year reprieve in September 2023 after investigators discovered he had concealed 54. 2 million yuan in offshore deposits managed by relatives. The court found Wang had used his position to grant loans to cooperators who then funneled kickbacks to his family’s overseas accounts.

To institutionalize this crackdown, the Communist Party Central Committee issued strict regulations in June 2022, which were rigorously enforced starting in 2024. The rules compel officials at the department level and above to report the business activities of their spouses and children annually. The directive presents a binary choice: the family exits the business, or the official exits the post. In 2024 alone, the Organization Department reported that over 4, 000 officials were “adjusted”—demoted or transferred—after failing to disentangle their families from commercial interests. This regulatory cage has decimated the “princeling economy,” where children of the elite previously traded on their surnames to secure equity in private equity and real estate ventures.

“The family style is the line of defense against corruption. When the spouse becomes a greed-keeper and the children become money-launderers, the home becomes a prison.”

— CCDI Commentary, Inspection and Supervision Daily, January 2025.

The case of Zhang Hongli, former senior executive at ICBC, further illustrates the retroactive reach of these investigations. Although Zhang resigned in 2018 citing “family reasons,” he was placed under investigation in late 2023 and expelled from the Party in 2024. The probe revealed that his resignation was a strategic retreat to shield a network of family-held assets that had benefited from his tenure. The CCDI’s findings emphasized that “retirement is not a safe landing,” the assumption that leaving office wipes the slate clean for family wealth accumulation.

Big Data Surveillance: AI Algorithms Tracking Official Assets

The transition from human-led investigations to algorithmic omniscience marks the most aggressive shift in Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption strategy since 2012. By late 2025, the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI) had fully operationalized a “Smart Supervision” (Zhihui Jiandu) grid that renders the financial lives of 90 million party members transparent to the state. This digital panopticon does not rely on whistleblowers; it relies on code.

At the core of this apparatus is the evolution of the “Zero Trust” system. Originally developed by the Chinese Academy of Sciences and piloted in 30 counties, the system was designed to cross-reference over 150 protected databases—spanning banking, property, construction, and travel records. Early pilots in Hunan and Jiangxi proved ruthlessly, identifying 8, 721 officials engaged in irregularities such as unexplained asset transfers or nepotistic land deals. While public reports in 2019 suggested the system was paused due to “bureaucratic pushback,” internal CCDI directives from 2024 indicate the technology was not abandoned but sublimated into a classified internal control method, deployed at the provincial level under the “Smart Supervision” banner.

The algorithms function on a principle of anomaly detection. If an official’s declared income is 200, 000 yuan, but their digital footprint—combined with spousal spending and children’s tuition—exceeds 2 million yuan, the system triggers an automatic “Red Flag” alert. This automated tripwire removes the human element of protection networks; a local party secretary cannot call a server to ask for a favor.

The Guizhou Paradox: Purging the Data Keepers

Nowhere is the collision between big data and corruption more visible than in Guizhou province, China’s national big data hub. In a clear irony, the very officials tasked with building this digital infrastructure became its primary. In February 2025, the CCDI announced the investigation of Jing Yaping, the former director of the Guizhou Big Data Development Administration, for “serious violations of discipline and law.”

Jing’s downfall followed the probe into her predecessor, Ma Ningyu, creating a complete decapitation of the province’s data leadership. Investigators found that the opacity of the tech sector had allowed officials to treat data center construction contracts as personal fiefdoms. While rumors circulated on social media about officials mining cryptocurrency on government servers, the verified charges focused on the traditional extraction of bribes through high-tech procurement channels. The purge in Guizhou demonstrates that the “data cage” is being used to trap the architects of the cage itself.

The e-CNY Trap and the Fall of Yao Qian

The most sophisticated of this surveillance is the integration of the digital yuan (e-CNY). Unlike cash or traditional bank transfers, e-CNY is programmable money that leaves an immutable ledger of every transaction. The CCDI has begun requiring senior officials in pilot regions to receive salaries and pay for government procurement exclusively in e-CNY, closing the loop on money laundering.

Yet, the system’s reach has proven absolute, sparing no one. In January 2026, state media aired a documentary revealing the conviction of Yao Qian, the former head of the People’s Bank of China’s Digital Currency Research Institute—the very “architect” of the digital yuan. Yao was found guilty of accepting bribes in cryptocurrency, specifically 2, 000 Ethereum (ETH), and using his technical expertise to mask illicit flows. His capture sends a chilling message to the bureaucracy: if the creator of the surveillance currency cannot hide his tracks, no one can.

| System Name | Primary Function | Data Sources Integrated | 2025 Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Smart Supervision (Zhihui Jiandu) | Automated anomaly detection for asset-income mismatches. | Bank records, property deeds, tax filings, family travel data. | Active in 16 provinces; mandatory for Vice-Ministerial ranks. |

| e-CNY Traceability | Real-time tracking of fiscal funds and official salaries. | Central Bank digital ledger, merchant payment logs. | Standard for government procurement in pilot zones (e. g., Suzhou, Xiong’an). |

| Skynet (Tianwang) | Fugitive repatriation and facial recognition tracking. | 600M+ surveillance cameras, border control, flight manifests. | Recovered $7. 6 billion in assets (2021-2025). |

| Zero Trust (Legacy/Internal) | Predictive policing for corruption risk. | Construction bids, land transfer records, satellite imagery. | Subsumed into CCDI internal investigative toolkit. |

Algorithmic Governance as Permanent Purge

The implementation of these systems signifies a move toward ” control.” The goal is no longer just to catch corrupt officials but to create a psychological environment where corruption is mathematically impossible to conceal. The “Smart Supervision” platforms generate weekly “Integrity Risk Maps” for provincial leaders, color-coding departments based on the frequency of financial anomalies.

This method has also depersonalized the purge. An algorithm does not care about factional loyalty or revolutionary lineage. In 2025 alone, the system flagged over 45, 000 “minor violations”—such as unauthorized dinners or undeclared gift cards—that previously would have gone unnoticed. These minor flags accumulate into a “Integrity Score” that determines promotion eligibility, automating the personnel management of the Communist Party.

The Third Plenum Aftermath: Intensifying the Crackdown

The Third Plenum of the 20th Central Committee, convened in July 2024 after a significant delay, was anticipated by observers as a moment for economic recalibration. Instead, it functioned as a ritualized confirmation of the party’s internal cannibalization. Far from signaling a conclusion to the turbulence that had removed a foreign minister and a defense minister in quick succession, the session institutionalized the purge. The communiqué released on July 18, 2024, did not accept the resignation of Qin Gang and confirm the expulsion of Li Shangfu; it codified a new, aggressive legal framework targeting “cross-border corruption,” signaling that the hunt for “tigers” would no longer be constrained by national borders.

The immediate aftermath of the Plenum dismantled the notion of “untouchable” sectors. By late 2024, the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI) had pivoted from individual takedowns to widespread decapitations of entire ministries. The focus shifted to the “soil of corruption”—a phrase used repeatedly in state media to justify the indefinite extension of investigations. This period marked the transition from removing rivals to the patronage networks in the state’s most serious organs: food security, elite sports, and the armed forces.

The intensity of this phase is best illustrated by the sheer rank of the officials targeted between the Plenum’s conclusion and the end of 2025. The CCDI’s dragnet ensnared full members of the Central Committee and leaders of state-owned monopolies with increasing velocity.

| Official | Last Position Held | Action Date | Outcome/Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tang Renjian | Minister of Agriculture and Rural Affairs | Expelled Nov 2024 | Sentenced to death with reprieve (Sept 2025) |

| Gou Zhongwen | Director, General Administration of Sport | Expelled Dec 2024 | Expelled for “damaging political ecosystem” of sports |

| Sun Zhigang | Party Secretary of Guizhou | Sentenced Oct 2024 | Death sentence with reprieve (bribes: 813 million yuan) |

| He Weidong | Vice Chairman, Central Military Commission | Expelled Oct 2025 | Stripped of rank; transferred for judicial review |

| Miao Hua | Director, CMC Political Work Department | Expelled Oct 2025 | Removed from all posts; under investigation |

| Zhang Shiping | Vice Chair, All-China Federation of Trade Unions | Investigated Dec 2025 | Identified as the “65th Tiger” of 2025 |