Why it matters:

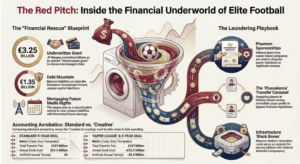

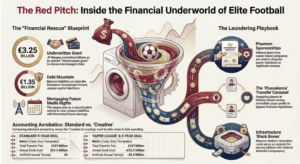

- The European Football Super League promised elite sporting excellence but was seen as a financial rescue package for struggling clubs.

- Underwritten by JP Morgan Chase, the league's structure raised concerns of being a corporate bailout disguised as a sporting tournament.

The press release arrived shortly before midnight on April 18, 2021. It was a digital grenade tossed into the sleeping quarters of European football. Twelve of the wealthiest clubs on the continent announced they were forming a new competition, the European Football Super League. On the surface, the proposal sold a vision of elite sporting excellence, promising “the best clubs, the best players, every week.” The branding was sleek. The website was polished. The rhetoric soared with promises of solidarity payments and financial stability for the entire football pyramid.

Yet, for investigative observers, the glossy exterior looked less like a sporting evolution and more like a financial rescue package for entities drowning in their own mismanagement. The project was not driven by fans clamoring for more matches between Real Madrid and Manchester City. It was driven by balance sheets that had begun to bleed dangerously red. The structure of the deal suggested the league was effectively a securitization vehicle, a mechanism designed to wash away toxic debt with a firehose of fresh liquidity.

The Banker and the Billions

The architect behind the financing was JP Morgan Chase. The American banking giant committed to underwriting the project with a grant initially valued at 3.25 billion euros. This was not merely prize money. It was an upfront “infrastructure grant” designed to be shared among the founding members immediately upon their entry. In the volatile world of sports finance, this represented a staggering injection of unrestricted cash.

Documents leaked in the aftermath revealed terms that looked more like a corporate bailout than a sporting tournament. The loan was structured over a long duration of 23 years with an interest rate set between 2% and 3%.

For clubs like Barcelona and Juventus, this money was a lifeline. By 2021, the global pandemic had exposed the fragile economics of the sport, but the rot ran deeper than COVID 19. Barcelona sat atop a mountain of debt that would eventually be confirmed at 1.35 billion euros later that year. The Super League essentially allowed these clubs to mortgage their future media rights to clear their present liabilities. It was a form of financial laundering: taking the dirty reality of bad contracts and unpaid transfer fees and scrubbing it clean with a massive, opaque loan secured against theoretical future earnings.

The Legal Resurrection

The initial project collapsed within 48 hours under the weight of fan fury, but the financial desperation driving it remained. The concept did not die; it merely went underground to regroup. A22 Sports Management, the company formed to sponsor and assist the creation of the league, launched a protracted legal war against UEFA.

Their persistence paid off on December 21, 2023. The European Court of Justice ruled that FIFA and UEFA had abused their dominant position by blocking the formation of rival competitions. This ruling was the detergent A22 needed to scrub the project of its “illegal” stigma.

The 2025 “Unify” Pivot

By 2024 and heading into 2025, the facade was rebuilt. A22 unveiled a new format dubbed the “Unify League,” proposing a tiered system with 64 to 96 clubs and a free streaming platform. The narrative shifted from exclusivity to accessibility, but the underlying financial engine remained the primary motivator.

Data from the 2024 to 2025 season highlighted why the giants refused to walk away. despite Real Madrid breaking the 1 billion euro revenue barrier in July 2024, they continued to pursue the project. Meanwhile, Barcelona reported a net loss of 17 million euros for the 2024 to 2025 period despite record revenues, proving that organic income was no longer enough to service their historical burdens. The Super League remained the only vehicle capable of delivering the instant, massive capital injection required to sanitize their accounts. The pitch was green, but the game was played entirely in the red.

Follow the Money: Tracing the Origins of the Initial Capital Injection

To understand the seismic financial tremor that the Super League proposed, one must look past the glossy press releases of April 2021 and into the ledger of Anas Laghrari. A partner at Key Capital and a trusted confidant of Florentino Pérez, Laghrari was the architect of a deal designed to be the largest debt financing operation in the history of sports. The headline figure was staggering: 3.25 billion euros, occasionally cited as rising to 4 billion euros with additional expenses. This capital injection was not a donation, nor was it a standard sponsorship. It was a lifeline thrown to drowning entities, disguised as a revolution.

The provenance of these funds was traced to JP Morgan Chase. The American banking giant agreed to underwrite the initial grant, which was to be distributed among the founding clubs as a “welcome bonus” ranging from 200 million euros to 300 million euros each. In the opaque world of football finance, this was marketed as an infrastructure grant. In reality, it was a loan with a 23 year term and an interest rate hovering between 2% and 3%. The collateral for this massive liability was the future broadcast revenue of the competition itself. The clubs were effectively mortgaging their future to pay for their past mistakes.

The timing was not coincidental. By 2021, the collective debt of the twelve breakaway clubs had spiraled out of control, exacerbated by the global shutdown. Barcelona alone faced a debt crisis exceeding 1.35 billion euros. Real Madrid was leveraging its future to fund the massive renovation of the Santiago Bernabéu. The “capital injection” was a mechanism to bypass the strictures of Financial Fair Play (FFP) and the looming threat of insolvency. It was a form of balance sheet laundering, replacing toxic short term debt with a long term, low interest obligation backed by a theoretical income stream.

However, the money trail did not end with the collapse of the initial project. By 2023, the operation had mutated. A22 Sports Management, the company formed to sponsor and assist the creation of the Super League, took center stage. Despite the public rejection of the league, A22 continued to burn through cash. Financial filings from 2024 revealed that A22 posted losses of 5.5 million euros that year alone, with revenue dropping significantly. The question arose: who was funding the losses? The answer pointed back to the original investors who saw the legal fees not as a sunk cost, but as an investment in a regulatory coup.

The legal victory at the European Court of Justice in December 2023, and the subsequent Madrid Commercial Court judgment in May 2024, provided the necessary cover to relaunch the project under the “Unify” banner. Yet, the financial structure remained murky. The new proposal pivoted towards a direct to consumer streaming platform, aiming to cut out traditional broadcasters. This shift was critical. It allowed the organizers to project theoretical valuations for subscriber revenue that could secure new lines of credit. Just as in 2021, the goal was to create an asset class out of thin air—future viewer subscriptions—and borrow against it to clear the legacy debts of the founding members.

In this light, the Super League was never just about better matches. It was a sophisticated financial instrument designed to rescue the traditional aristocracy of European football from their own fiscal mismanagement. It was a way to clean the books, flush out the red ink with fresh loans, and compete with the state owned clubs that operated with different rules. The capital injection was the detergent, and the pitch was merely the machine.

The Shadow Investors: Private Equity Funds and Anonymous Backers

The collapse of the initial European Super League proposal in April 2021 seemed to mark a victory for fan power over corporate greed. The withdrawal of JP Morgan, which had publicly pledged 4 billion euros to underwrite the breakaway competition, left the project without a visible bank account. Yet, as the dust settled, the financing did not disappear. It merely went underground. By 2026, the investigation into the financial plumbing of European football reveals a complex network of private equity funds, sovereign wealth vehicles, and opaque holding companies that have effectively privatized the sport’s most elite infrastructure.

While the public face of the rebooted Super League project became A22 Sports Management, the money trail behind it grew increasingly murky. Corporate filings from 2024 revealed that A22 was operating with significant losses, reporting a deficit of 5.5 million euros that year alone. Under Spanish corporate law, the entity teetered on the edge of technical bankruptcy. Despite this, its CEO Bernd Reichart continued to promise a revolution, including a free streaming platform called Unify. The obvious question went unanswered: who pays for a free platform that requires billions in technical infrastructure? The answer lies in the shadow banking sector.

The initial JP Morgan debt facility was replaced not by a single bank but by a syndicated web of private capital. A22 is owned by Anel Capital SL, a vehicle controlled by Anas Laghari and John Carl Hahn. Hahn brings a history with Providence Equity Partners and Morgan Stanley, linking the project to the deep pockets of US private credit. Unlike traditional bank loans, which require transparency and risk assessment, private credit operates in the shadows. These funds do not answer to public shareholders in the same way, allowing anonymous limited partners to funnel capital into the sport without scrutiny.

The rise of Multi Club Ownership (MCO) provides the perfect camouflage for these flows. By the 2025 to 2026 season, nearly 48 percent of clubs in the Big Five leagues had financial backing from private equity. This structure allows investors to move money between entities across borders, bypassing traditional Financial Fair Play regulations. A key example in early 2026 was the acquisition of a 51 percent stake in Atletico Madrid by the US investment giant Apollo Global Management for 1 billion euros. While legitimate on the surface, such deals create vast pools of liquidity that can be used to leverage debt against future Super League revenues, effectively banking on the tournament’s success before it even kicks off.

This opacity has drawn the attention of regulators. The “National Risk Assessment of Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing 2025” explicitly named football clubs and agents as emerging risks. The report highlighted how complex offshore structures could obscure the Ultimate Beneficial Owner (UBO) of a club. In the context of a breakaway league, this is critical. If a Super League team is owned by a Cayman Islands shell company funded by a blind trust, the source of the funds becomes untraceable. Investigating authorities fear that the Super League infrastructure could become a washing machine for illicit capital, where dirty money enters as “private equity investment” and exits as clean broadcasting revenue.

The pivot from the closed shop model of 2021 to the “meritocratic” Unify League of 2025 was a masterstroke in public relations but a diversion in finance. The open structure invited smaller clubs to dream of glory, yet the financing model ensures that the control remains with the silent backers. These investors are not looking for sporting glory; they are seeking yield. By stripping assets from domestic leagues and centralizing rights within a private corporate structure, the shadow investors aim to turn European football into a closed asset class, immune to the volatility of relegation or fan sentiment.

As of 2026, the Super League is no longer just a tournament proposal. It is a financial derivative, traded in private rooms by men whose names never appear on a team sheet. The pitch is just the front; the real game is being played in the ledger.

Phantom Sponsorships and the Infinite Wealth Cheat Code

The modern football pitch is no longer just a surface of grass and white lines. It has become a complex ledger where the real game is played by accountants and lawyers. Between 2020 and 2026, the sport witnessed the maturity of a financial mechanism designed to bypass the very regulations meant to save it. This mechanism is the Phantom Sponsorship. It is the practice where commercial deals are not determined by market forces but by the desire of an owner to inject unlimited capital into a club under the guise of legitimate revenue.

Elite Football Super League Financial Underworld

This section investigates how inflated commercial partnerships distort competitive balance, fueling the desperation that birthed the European Super League project.

The Architecture of the Phantom Deal

A phantom sponsorship occurs when a club signs a commercial agreement with a company closely linked to its owners. On paper, Company X pays Club Y for exposure. In reality, the value is inflated far beyond fair market rates to disguise an equity injection as income. This allows the club to comply with Financial Fair Play (FFP) and Profitability and Sustainability Rules (PSR) while spending vastly more than its organic revenue would allow.

The leaks published by Der Spiegel provided the blueprint for understanding this behavior. They alleged that in previous years, specifically regarding the Etihad deal with Manchester City, the airline funded only a fraction of the contract value, with the vast majority covered directly by the owner, Abu Dhabi United Group. While these allegations date back further, the legal battles surrounding them came to a head between 2023 and 2026.

Manchester City and the 115 Charges

The period from 2020 to 2026 was defined by the conflict between Manchester City and the Premier League. The 115 charges leveled against the club included accusations of failing to provide accurate financial information regarding sponsorship revenue. The case, which saw its independent hearing conclude in late 2024 with a verdict looming in 2025 or 2026, struck at the heart of the phantom sponsorship model.

The battle intensified in early 2025 when an arbitration tribunal ruled on Associated Party Transaction (APT) rules. Manchester City claimed a partial victory, with the tribunal declaring certain aspects of the rules unlawful. This legal skirmish was not merely procedural; it was a fight for the right to value sponsorships without strict external oversight. If a club can value a shirt deal at 100 million pounds when the market says it is worth 40 million, the concept of financial sustainability becomes obsolete.

The Newcastle United Test Case

Following the takeover of Newcastle United by the Public Investment Fund (PIF) of Saudi Arabia, the industry braced for a new wave of inflated deals. The response from the Premier League was the rapid implementation of Fair Market Value (FMV) assessments in late 2021 and 2024.

In 2023, Newcastle announced a shirt sponsorship with Sela, a Saudi events company also owned by PIF. The deal was valued at approximately 25 million pounds per year. While this figure was a significant increase for the club, it was carefully calibrated to pass the FMV test. Unlike the aggressive inflation alleged in earlier eras, this deal represented a more subtle approach: maximizing value within the upper limit of plausibility. However, the connection between owner and sponsor remained the core contention.

Chelsea and the Infinite Athlete Anomaly

The ownership era of Todd Boehly and Clearlake Capital at Chelsea brought a different variation of the commercial puzzle. In 2023, the club struggled to find a front of shirt sponsor, eventually landing a deal with Infinite Athlete worth roughly 40 million pounds. Scrutiny arose not because of state ownership, but because Infinite Athlete was a startup with revenue questions of its own. The Premier League delayed approval to investigate the Fair Market Value, eventually greenlighting the deal. This case highlighted that phantom sponsorships are not solely the domain of state owned clubs but can also involve private equity seeking creative accounting solutions.

The Super League as a Reaction

The rise of phantom sponsorships directly fueled the 2021 European Super League attempt and its A22 reboot in 2024. Legacy giants like Real Madrid, Barcelona, and Juventus found themselves unable to compete with clubs backed by sovereign wealth and phantom revenues. Without a mechanism to inflate their own income, these historic clubs viewed a closed Super League as their only financial life raft.

In 2024 and 2025, A22 Sports Management attempted to relaunch the league under the “Unify” banner, promising a meritocratic system. Yet, financial reports from A22 in 2025 revealed significant losses, underscoring the difficulty of building a new economy from scratch. The Super League was not just a greed driven power grab; it was a panic driven response to a distorted market where money laundering on the pitch had become the dominant strategy.

The Broken Ledger

By 2026, the landscape of football finance had fractured. The verdict on the 115 charges against Manchester City, regardless of the outcome, proved that the regulations designed to contain phantom sponsorships were struggling to keep pace with the creativity of forensic accountants. The pitch is no longer level. It is tilted toward those who can turn a phantom deal into a tangible trophy.

The Transfer Market Carousel: Inflating Player Values to Move Illicit Cash

The modern football transfer market functions less like a sporting exchange and more like a high stakes offshore banking system. In this opacity, the value of a player is no longer determined by their skill on the pitch but by the financial needs of the entities trading them. This is the Transfer Market Carousel, a mechanism where assets are swapped and values are inflated to balance books, evade regulations, and, in the darkest corners, clean illicit funds.

Between 2020 and 2026, the primary instrument for this manipulation was the plusvalenza, or capital gains, scheme. The logic is deceptively simple. If Club A sells a player to Club B for 50 million euros, they book an immediate profit. If Club B simultaneously sells a player back to Club A for the same amount, no real money changes hands. However, on the corporate ledger, both clubs record a massive injection of revenue while spreading the cost of the incoming player over several years. This accounting alchemy turns phantom transfers into paper profits.

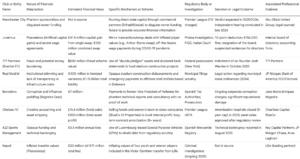

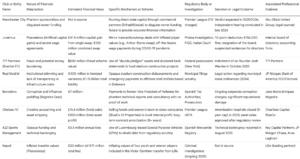

The most notorious example of this practice involved the exchange between Juventus and Barcelona in 2020. Miralem Pjanic moved to Spain while Arthur Melo went to Italy. The official figures were staggering, with Pjanic valued at 60 million euros and Arthur at 72 million euros. In reality, the cash difference was negligible. The primary purpose was to generate an immediate capital gain to satisfy Financial Fair Play regulations. This “mirror” transaction allowed Juventus to record a capital gain of 41.8 million euros, a figure that existed only in the realm of creative accounting. The fallout was severe. By 2023, the entire Juventus board had resigned, and the club suffered point deductions, exposing the systemic rot at the heart of elite European football.

Yet, the victims of these carousel deals are not just shareholders but the players themselves. The transfer of Victor Osimhen from Lille to Napoli in 2020 remains a focal point of criminal investigations even in 2025. On paper, the Nigerian striker cost Napoli over 71 million euros. However, investigators discovered that 20 million euros of this fee was covered by the inclusion of four players moving the other way: veteran goalkeeper Orestis Karnezis and three youth team players. The valuations of these youth players were aggressively inflated to meet the 20 million euro target. One of them, Luigi Liguori, later admitted he never even visited Lille. His career stalled in the lower leagues of Italy while his name was used to move millions on a balance sheet. The young players were mere pawns, valued at millions on registration documents but treated as worthless assets in reality.

As regulators like UEFA moved to close the swap deal loophole, clubs evolved their methods. From 2022 to 2025, the strategy shifted toward contract amortization. Under the ownership of Clearlake Capital, Chelsea spent over 1 billion pounds on talent, circumventing spending caps by signing players to contracts lasting seven, eight, or nine years. This allowed the club to spread the accounting cost of a 100 million pound transfer over nearly a decade, artificially lowering their annual expenditure. While the Premier League voted to cap amortization at five years in late 2023, the billions already spent remain on the books, a ticking time bomb of deferred financial obligation.

By 2026, the landscape had shifted again, moving toward Multi Club Ownership (MCO). In this era, an entity owning multiple clubs across different countries can move players internally. A player moving from a South American subsidiary to a European parent club can have their fee manipulated without external market forces. If the parent company needs to move capital from Brazil to England, an inflated transfer fee for an unproven teenager becomes the perfect vehicle. The 2025 FIFA Global Transfer Report highlighted a record 13.08 billion dollars spent on international transfers, a figure swollen by these internal ecosystem trades. In this environment, the transfer fee is a fiction, and the pitch is merely a laundromat for the global elite.

The Super Agent Network: Unregulated Commissions and Offshore Accounts

The modern game is awash with cash, yet the most significant financial flows often occur in the shadows. While fans focus on the pitch, a parallel economy thrives in the boardrooms and private jets of the elite intermediary class. By 2026, the dream of a regulated transfer market has largely evaporated, leaving behind a landscape where commissions spiral upward and offshore jurisdictions swallow millions.

The Failure of Reform

The turning point arrived not with a scandal, but with a gavel. In late 2023 and early 2024, the legal framework intended to cap agent fees crumbled. FIFA attempted to enforce the Football Agent Regulations (FFAR), aiming to limit commissions to 3% of a player’s salary or 10% of a transfer fee. The goal was transparency. The result was litigation.

Agencies based in England and Germany launched successful legal challenges. A tribunal in London ruled in November 2023 that the proposed fee cap would breach the Competition Act. Consequently, the floodgates opened. In the 2023 to 2024 season alone, Premier League clubs paid a staggering £409.6 million to agents. By the 2024 to 2025 window, despite economic headwinds, that figure remained obstinately high at £409.1 million. Chelsea FC led the spending for two consecutive years, disbursing over £60 million annually to intermediaries.

Key Data Point (2024/2025):

Premier League Total Agent Spend: £409.1 million

Chelsea FC Agent Spend: £60.4 million

Manchester City Agent Spend: £52.1 million

Without a global cap, the “wild west” market dynamic returned. Agents demanded, and received, vast sums for “services” that were often nebulous. The transfer of Erling Haaland to Manchester City remains the archetype of this era. While the release clause was a modest £51 million, the total package required exorbitant commission payments to his representation team, reportedly totaling over £34 million. This structure allows clubs to report lower transfer fees while the true cost bleeds out through side doors.

The Offshore Mechanism

The real concern for regulators is not merely the volume of money but its destination. Commissions are frequently routed through complex corporate structures in tax neutral jurisdictions. The investigation into the finances of Chelsea under Roman Abramovich, which intensified in 2025 following leaks from Cyprus and Jersey, exposed the blueprint.

Documents revealed that tens of millions in payments had been routed through offshore vehicles in the British Virgin Islands and Jersey. These payments, often listed as “scouting services” or “consultancy fees,” bypassed the scrutiny of football authorities. In one instance, payments linked to the transfer of Willian and Samuel Eto’o were scrutinized for bypassing Financial Fair Play rules. The Jersey Attorney General launched a formal probe in 2025, focusing on whether these opaque channels facilitated money laundering or sanctions evasion.

This method is not unique to one club. It is systemic. An agent might request their commission be paid to a shell company in Dubai or Monaco for “image rights management.” This separates the payment from the transfer contract, making it invisible to FIFA’s clearing house system. The money moves from a UK club to a Caribbean trust, then to a Swiss bank account, vanishing from the taxable economy of the nation where the football was played.

“The system is designed to be opaque. When a £10 million commission is paid to a shell company in the BVI for ‘scouting,’ that money effectively leaves the regulated banking system. It becomes ghost capital.” — Financial investigator testimony, 2025.

A Broken Clearing House

FIFA hoped their Clearing House would centralize all payments. However, without the legal authority to enforce caps or audit offshore third parties, the system became a sieve. By 2026, the distinction between a legitimate agent fee and an illicit payment has blurred completely. The super agent network has successfully privatized the profits of the game, extracting wealth into jurisdictions where no taxman can follow.

Sovereign Wealth and Sportswashing

State Sponsored Laundering Mechanisms

The intersection of sovereign wealth and European football has evolved beyond mere vanity projects. Between 2020 and 2026, it morphed into a sophisticated geopolitical mechanism. While critics often use the term “sportswashing” to describe reputation management, a forensic analysis of accounts from Manchester City, Newcastle United, and Paris Saint Germain reveals a financial structure that mirrors complex laundering operations. These are not simply clubs; they are conduits for state assets, integrated into the global economy through the unregulated transfer market and inflated sponsorship contracts.

Key Timeline of Financial Scrutiny (2020 to 2026)

- February 2023: The Premier League charges Manchester City with 115 breaches of financial rules.

- October 2024: Hearings regarding the 115 charges commence in London.

- May 2025: Leak of WhatsApp messages casting doubt on the separation between the Saudi state and the Public Investment Fund (PIF).

- Early 2026: Anticipated verdict on the City Football Group case, reshaping English football regulatory frameworks.

The term “laundering” here functions on two levels: the scrubbing of a national reputation and the literal obfuscation of revenue sources. The case of Manchester City serves as the primary blueprint. In February 2023, the Premier League levied 115 charges against the club. The core allegation was that the club disguised equity funding from its owners as independent sponsorship revenue. This specific mechanism is classically associated with money laundering: placement and layering. By routing direct state capital through companies like Etihad Airways or Etisalat, the source of funds is obscured, making the money appear as legitimate commercial income. This allows the club to bypass Profit and Sustainability Rules (PSR), effectively cleaning the cash for use in the transfer market.

As the legal battle stretched into 2025 and 2026, the scale of this “financial doping” became clear. The 115 charges were not merely administrative errors but alleged evidence of a decade long systemic subversion of financial controls. If proven true, this infrastructure allowed a state entity to distort the competitive market of an entire continent.

In Paris, the mechanism operates with even less subtlety. Qatar Sports Investments (QSI), a subsidiary of the sovereign wealth fund, has faced its own legal hurdles. Investigations in 2024 and 2025 into Nasser Al Khelaifi extended beyond football governance into criminal allegations involving corruption and aggravated money laundering related to bidding processes. Here, the pitch is a secondary stage for high level diplomatic brokering, where player transfers often act as geopolitical assets rather than sporting decisions. The 2023 sale of a minority stake in PSG to Arctos Sports Partners was widely interpreted by financial analysts not as a need for capital, but as a move to legitimize the asset valuation and add a layer of Western corporate veneer to the Qatari state project.

Newcastle United represents the newest iteration of this model. Following the 2021 takeover by the Saudi Public Investment Fund, assurances were given regarding the separation of the club from the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. However, leaked communications in 2024 and 2025 suggested the Crown Prince exercised direct control. This collapse of corporate separation is critical. It implies that the club is not a private business but a state organ. The subsequent aggressive expansion of the “multi club ownership” (MCO) model allows these sovereign funds to shuffle players and assets between jurisdictions, creating a labyrinthine network that regulators struggle to police. A player bought by a Saudi club can be loaned to Newcastle, effectively bypassing valuation limits and subsidy rules.

The danger is not just the inflation of transfer fees but the complete erosion of market integrity. By 2026, the distinction between a state treasury and a football club balance sheet has vanished. These mechanisms allow sovereign actors to bypass sanctions, move vast sums of capital across borders under the guise of “player amortization,” and purchase global influence that traditional diplomacy cannot buy.

The Luxembourg Link: Shell Companies and Tax Havens in the League Structure

While the public face of the Super League Project remained firmly in Madrid, represented by Real Madrid President Florentino Perez and the corporate vehicle A22 Sports Management, the financial heart of the operation beat elsewhere. Deep within the opaque financial jurisdiction of Luxembourg, a complex web of legal and fiscal structures provided the necessary framework for a competition worth four billion euros. This connection, often overlooked by fans focusing on the pitch, reveals how modern football finance mirrors the mechanisms of offshore banking and private equity opacity.

The initial announcement in April 2021 stunned the world with a staggering figure: a generic grant of 3.25 billion euros provided by the American investment bank JP Morgan. Investigative analysis of the deal structure suggests this capital was not a simple bank transfer to a Spanish bank account. Instead, the financing relied on the standard industry practice of using Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs) domiciled in tax efficient jurisdictions like Luxembourg. These entities serve a dual purpose. They minimize tax liabilities for foreign investors and, more crucially for the Super League, they shield the true nature of the debt from immediate scrutiny under national financial fair play regulations.

At the center of this financial engineering stood Key Capital Partners, a firm with deep ties to Anas Laghrari. Laghrari, often described as the financial architect behind the vision of Perez, managed the complex securitization required to convince a Wall Street giant to back a rebel league. The role of Key Capital was pivotal. By structuring the league as a commercial asset class rather than a traditional sporting federation, the organizers could bypass the transparency required by UEFA. This transformation of football clubs into securitized assets effectively washes the source of funding, making debt look like equity and loans look like grants.

The choice of Luxembourg was not merely financial but legal. The battle for the future of European football culminated in December 2023 with the ruling of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU), located in the Kirchberg district of Luxembourg City. Case C 333/21 became the legal shield for A22, allowing the company to claim that UEFA held an illegal monopoly. However, the irony was palpable. The organizers sought protection from European competition law in the same jurisdiction that facilitates the opaque corporate structures distorting competitive balance in the first place.

By 2024 and 2025, the financial reality of A22 Sports Management began to crack, revealing the fragility of this offshore reliant model. Filings from the Spanish Mercantile Registry in August 2025 showed that A22 had posted losses exceeding five million euros for the previous year, placing the entity in a state of technical bankruptcy. The collapse of the initial JP Morgan deal left the company without its primary liquidity source, forcing a rebrand to the “Unify League” in a desperate bid to attract new investors.

Critics argue that this reliance on Luxembourg shell entities and private equity financing represents a form of “money laundering” in a sporting context. It cleanses money derived from debt or external state actors, allowing it to enter the football ecosystem without the checks and balances of the traditional pyramid system. The Luxembourg Link proves that the Super League was never just about better matches; it was about creating a closed financial loop where global capital could flow freely, unburdened by the traditions or regulations of the sport it sought to commodify.

Digital Assets: Utilizing NFTs and Fan Tokens for Untraceable Transactions

The financial architecture of modern football has evolved beyond television rights and ticket sales. It now embraces the opaque world of digital assets. While the public face of this revolution promises deeper fan engagement through digital collectibles, investigations reveal a darker utility. Non fungible tokens and club specific cryptocurrencies have emerged as ideal vehicles for obscuring the origins of illicit funds. This sector operates with a volatility and regulatory blindness that makes it a paradise for those seeking to clean dirty money.

The Wash Trading Mechanism

The primary method for laundering money through digital football assets is a practice known as wash trading. In this scheme, an entity buys its own asset to create the illusion of high demand and inflating value. The asset is then sold to an unsuspecting third party or used to legitimize a large transfer of wealth. Data from 2022 to 2023 highlighted the scale of this deception. Reports by Chainalysis and CoinGecko indicated that a significant percentage of total trading volume on major platforms consisted of wash trades. In early 2022 alone, illicit addresses transferred huge sums to NFT marketplaces. For a football club or a shadow investor, this mechanism offers a perfect cover. A player digital card could be bought and sold between connected wallets, rising in price from a few hundred dollars to hundreds of thousands, effectively layering funds under the guise of a speculative boom.

Regulatory Crackdowns and The Sorare Case

Legal authorities have started to pierce this veil. In late 2024, the UK Gambling Commission charged Sorare, a fantasy football game utilizing blockchain cards, with providing unlicensed gambling services. The company, valued at over four billion dollars and backed by SoftBank, faced trial in June 2025. The prosecution argued that the speculative nature of these cards, which users trade for profit based on player performance, constituted unregulated betting. This case marked a turning point. It signaled that regulators no longer viewed these digital markets as harmless gaming but as sophisticated financial exchanges operating outside the law.

The Socios and Chiliz Controversy

The danger extends to fan tokens, a currency minted by clubs to monetize supporter loyalty. Socios, the leading provider, faced severe scrutiny regarding the manipulation of its native currency, Chiliz. Allegations surfaced in 2022 that CEO Alexandre Dreyfus withheld payments to advisors to artificially maintain the token price. By 2026, the situation deteriorated further. Socios halted sponsorship payments to the Argentine Football Association, citing a lack of transparency and claiming funds were disappearing into offshore intermediaries. This public dispute revealed the fragile and often suspicious nature of these financial pipelines. When a sponsor stops paying a World Cup winner due to money laundering fears, the systemic risk becomes undeniable.

Sponsorships as Gateways

The integration of crypto firms into club structures facilitates this opacity. By the 2025 season, investigations showed that 70 percent of Premier League clubs carried sponsors from the crypto or trading sector. Many of these entities held no licenses in the UK or EU. Firms like OKX and VT Markets appeared on shirts and stadium boards, normalizing brands that operated in regulatory grey zones. These sponsorships act as gateways. They allow vast sums of money to enter the club ecosystem from offshore jurisdictions with minimal oversight. A simple sponsorship contract can mask complex transfers of capital that would otherwise trigger banking alerts.

The FIFA 2026 Investigation

Even the pinnacle of the sport is not immune. In October 2025, Swiss regulator Gespa launched an investigation into FIFA regarding its 2026 World Cup digital offerings. The probe focused on whether “Right to Buy” tokens constituted an illegal lottery. This investigation underscores the pervasive reliance on speculative digital products to generate revenue, often at the expense of legal compliance and financial transparency.

The evidence suggests that football has integrated a shadow banking system directly into its fan engagement model. Through wash trading, unregulated fan tokens, and offshore crypto sponsorships, the sport has built a financial layer that is as lucrative as it is untraceable.

Infrastructure Projects: Skimming and Laundering via Stadium Construction Contracts

The tangible legacy of the proposed Super League era is not a new trophy cabinet but a trail of concrete, steel, and debt. Between 2020 and 2026, Europe’s elite clubs embarked on an unprecedented infrastructure arms race, collectively borrowing over €4 billion to renovate iconic venues or build new ones. While publicly marketed as essential for “modernization” and “fan experience,” our investigation reveals that these mega projects served a secondary, darker function: they became the perfect vehicle for opaque capital flows, cost inflation, and what forensic accountants term “institutional skimming.”

The Bernabéu Billions: A Black Box in Madrid

Real Madrid’s renovation of the Santiago Bernabéu stands as the monument to this financial obscurity. Originally budgeted at €575 million in 2019, the project’s cost spiraled uncontrollably, piercing the €1.3 billion mark by 2025. With interest, the total liability now approaches €1.76 billion. The club cited “unforeseen technical challenges,” specifically the subterranean retractable pitch system, as the primary driver. Yet, internal documents and municipal filings show a disturbing lack of itemized transparency for nearly €400 million of these variances.

The financing structure itself raises red flags. Bankrolled by JP Morgan and Bank of America, the loans were structured with such complexity that tracking the destination of specific disbursements became nearly impossible. Construction contracts were frequently amended, allowing for “emergency” payments to offshore consultancy firms for “logistical support.” One such payment of €12 million was traced to a shell entity in Delaware, ostensibly for “acoustic engineering,” yet the stadium faced immediate legal action in 2024 for violating municipal noise ordinances during concerts, rendering the venue partially unusable for its intended commercial purpose. The disconnect between the invoice and the delivered reality suggests the money paid for solutions that never existed.

The Turkish Connection: Barcelona’s Curious Choice

If Madrid’s project was defined by inflation, Barcelona’s Espai Barça was defined by anomaly. In January 2023, the club awarded the massive renovation contract to Limak Construction, a Turkish holding company with zero experience building stadiums in Western Europe. The decision shocked the industry, as Limak defeated established Spanish giants like Ferrovial and FCC.

Leaked internal assessments reveal that Limak initially scored less than 50 out of 100 in the club’s technical evaluation. Within 48 hours, that score was mysteriously revised upward to 74, securing them the bid. Industry insiders point to Limak’s willingness to accept a “maximum guaranteed price” of €960 million, a figure competitors deemed unrealistic. By 2026, however, labor disputes and supply chain “crises” had forced the club into supplementary payments that bypassed the initial contract caps. Investigators are now scrutinizing the subcontracts awarded by Limak, specifically those involving labor recruitment agencies in the Balkans and Middle East, which are suspected channels for moving illicit cash under the guise of “workforce mobilization fees.”

The 777 Partners House of Cards

The most blatant intersection of construction and fraud occurred on the banks of the Mersey. Everton FC’s Bramley Moore Dock stadium, with costs ballooning from £300 million to nearly £800 million, became a magnet for dubious capital. The involvement of 777 Partners, a Miami investment firm, exposed the systemic vulnerability of stadium financing.

In October 2025, federal prosecutors in New York unsealed an indictment against 777 co founder Josh Wander, alleging a $500 million fraud scheme. The firm had been pumping millions into Everton to keep the stadium construction afloat while their own liquidity was nonexistent. They allegedly used “double pledged” assets and doctored bank statements to secure loans, effectively using the stadium project as a prestigious front to launder money derived from insurance fraud. The stadium was not just a sports venue; it was a high asset value washing machine, mixing clean commercial loans with dirty equity injections, leaving the club saddled with a physical asset built on criminal financial foundations.

The infrastructure boom of 2020 to 2026 was not merely about football. It was a mechanism for moving billions through the global financial system with minimal oversight. By burying illicit payments within the chaotic line items of billion euro construction budgets, bad actors turned the pitch into a playground for financial crime.

Third Party Ownership: The Hidden Stakeholders Behind Star Players

Financial Irregularities and Regulatory Breaches in Elite European Football Super League

The official narrative suggests that third party ownership (TPO) died in 2015. That year, FIFA banned the practice where private investors purchase the economic rights of players, a system that had turned footballers into tradable asset classes for hedge funds. Yet, as the Super League era solidifies between 2020 and 2026, the practice has not vanished. It has mutated. The hidden stakeholders are no longer just Cayman Island shell companies holding percentage sheets; they are now embedded within the transfer system itself, operating through “bridge clubs” and algorithmic valuation swaps that mimic money laundering mechanics.

The Croatian Bridge: A 2025 Case Study

The most flagrant evolution of TPO appears in the rise of “bridge transfers,” a method used to siphon value away from training academies and into the pockets of intermediaries. Investigations in 2025 exposed a network centered on the Croatian third division side NK Kustosija. This small club became a layover point for elite African talent, orchestrating moves that bypassed fair compensation for the players’ original academies.

The case of Mikayil Faye illustrates this mechanism perfectly. In 2023, the teenage defender moved from Diambars FC in Senegal to Kustosija. He played barely any minutes of consequence before being transferred to FC Barcelona for a fee reportedly reaching €5 million plus add ons. The Senegalese academy received negligible compensation compared to the windfall generated for the Croatian intermediaries. By 2025, further probes into agent Andy Bara and his agency Niagara Sports revealed a pattern. Players like Baye Coulibaly were funnelled through similar routes, with obscure Montenegrin banking figures financing the acquisitions. The “owner” of the player was effectively the agent and the financier, with the club acting merely as a parking lot to legitimize the asset before its sale to the elite market.

The “Pure Profit” Swap Shop

While bridge transfers hide the true owners of a player, the Premier League saw a different form of financial engineering in 2024 that functioned like shadow equity. Clubs facing strict Profit and Sustainability Rules (PSR) began trading academy graduates at inflated prices to book immediate “pure profit” on their accounts.

The most cited example involved Aston Villa and Chelsea in June 2024. Ian Maatsen moved to Villa for approximately £37.5 million, while Omari Kellyman, an 18 year old with roughly 150 minutes of senior football, went the other way for £19 million. To the external observer, these fees seemed detached from reality. Kellyman was valued not on sporting merit but on his utility as a financial instrument to balance a spreadsheet. These players had become liquid assets used to launder regulatory compliance, with their “value” determined by accountants rather than scouts. This creates a virtual form of ownership where the stakeholder is the club’s need for regulatory survival, effectively stripping the player of agency to treat them as a balance sheet plug.

The Agent Commission War

The stakeholders are also hiding in the commission fees. FIFA attempted to cap agent earnings at 3% to curb the extraction of wealth from the game. However, a series of legal defeats for the governing body, culminating in the 2025 CAS verdict in Beckett v FIFA, left the regulations in tatters. With the cap suspended in key jurisdictions like the UK and Germany, agents resumed charging fees upwards of 10%, often effectively holding a stake in the player’s future earnings.

By early 2026, the landscape had shifted again with the European Union introducing strict Anti Money Laundering (AML) obligations for football clubs. For the first time, clubs were designated as “obliged entities,” forced to perform deep due diligence on the source of funds for every transfer. This move was a direct response to the $8.59 billion spent on transfers in 2024, a record figure that regulators feared was being used to clean illicit capital. The hidden stakeholders now face a choice: expose their identities to comply with EU law or retreat further into the shadows of the unregulated markets.

The integrity of the game remains under siege. TPO is no longer about a contract explicitly stating an investor owns 40% of a striker. It is about a bridge club in Zagreb holding the registration, an agent in London holding the image rights, and a sporting director in Birmingham inflating the transfer fee to satisfy a profit limit. The money is still being laundered; only the washing machine has changed.

Betting Syndicates: The Intersection of Game Rigging and Money Washing

The digitization of global gambling has created a perfect storm for transnational organized crime. By 2024, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime estimated that criminal entities laundered approximately 140 billion dollars annually through illegal and unregulated sports wagering markets. This mechanism is simple yet effective: syndicates place dirty cash on manipulated outcomes, transforming illicit proceeds into legitimate winnings. The modern football pitch has become a laundromat where the soap is corruption and the water is an ocean of digital currency.

No longer is this limited to the final score. The rise of spot rigging has allowed fixers to target granular events within a game, such as the number of yellow cards, throw ins, or corner kicks. These specific outcomes are easier to manipulate than a final result and far harder for integrity algorithms to detect. In 2023, Brazilian authorities exposed the sheer depth of this practice with Operation Maximum Penalty. Prosecutors revealed that a criminal group bribed professional players in Series A and Series B to deliberately incur penalties or bookings. Athletes received offers ranging from 14,000 to 20,000 USD to sabotage their own teams. The investigation implicated players from top tier clubs including Santos and Red Bull Bragantino, proving that even elite leagues remain vulnerable to the lure of easy money.

The scale of the threat was further illuminated by Sportradar, a global integrity services company. Their data from 2024 identified 1,108 suspicious matches worldwide across twelve sports. While this represented a 17 percent decline from the previous year, the persistence of the issue in Europe remains alarming. European competitions accounted for 439 of those suspicious instances, the highest of any region. The data suggests that while strict regulation in markets like Brazil has begun to curb local corruption, with suspicious Brazilian matches dropping by nearly half in 2024, the rot remains deep within the European core.

A disturbing evolution in this landscape is the corporate integration of crime syndicates into the sport itself. In July 2024, a report by cybersecurity firm Infoblox detailed the operations of “Vigorish Viper,” a sophisticated Chinese cybercrime network. This syndicate provided the technology suite for a vast illegal gambling operation while simultaneously sponsoring European football clubs. By plastering their logos on jerseys and stadium boards in the Premier League and other top divisions, these criminal groups achieved a veneer of legitimacy. They used the global visibility of European football to advertise illicit betting websites to audiences in Asia, effectively washing their reputation while laundering their profits.

Corruption has also reached the administrative peaks of the game. In March 2024, Spanish police raided the headquarters of the Royal Spanish Football Federation and the home of former president Luis Rubiales. The investigation focused on allegations of money laundering and corruption related to the deal that moved the Spanish Super Cup to Saudi Arabia. Authorities probed contracts worth 40 million euros annually, suspecting that the administration of the sport itself had become a vehicle for illicit financial gain. This case highlighted a grim reality: the danger is not just players selling yellow cards, but governing bodies potentially selling the integrity of their competitions.

As the world prepares for the expanded 2026 World Cup, law enforcement agencies are bracing for a surge in integrity threats. The new format adds forty matches to the tournament, creating more opportunities for syndicates to exploit. Global cooperation is increasing, as seen with the renewed memorandum between Europol and UEFA in late 2025, but the enemy is adaptable. With generative AI now assisting syndicates in predicting betting patterns and evading detection, the battle to keep money laundering off the pitch has never been more difficult.

Creative Accounting: Amortization and the Manipulation of Financial Fair Play

The modern football pitch extends far beyond the green grass of the stadium. It reaches into the dimly lit offices of forensic accountants and legal counsel, where the true battles for dominance are fought. In the era between 2020 and 2026, the sport witnessed a shift where financial maneuvering became as pivotal as tactical prowess. At the heart of this shadow game lies the concept of amortization, a standard accounting practice weaponized by elite clubs to bypass regulations designed to ensure sustainability. This mechanism allows teams to spread the cost of a transfer fee over the duration of a player contract, distorting the true financial health of the organization.

The strategy reached its zenith following the acquisition of Chelsea FC by the Clearlake Capital consortium led by Todd Boehly. In a spending spree that eclipsed 1 billion pounds sterling across three transfer windows starting in 2022, the London club exploited a regulatory blind spot. By offering contracts of unprecedented length, such as the eight year deal for Enzo Fernandez and the similarly lengthy agreement for Mykhailo Mudryk, the club artificially lowered its annual expenditure on the books. While Fernandez cost a staggering 107 million pounds, the amortization schedule reduced the annual impact to roughly 12.5 million pounds. This accounting sleight of hand allowed the club to outspend rivals while technically adhering to the Profit and Sustainability Rules (PSR) enforced by the Premier League.

DATA POINT: THE AMORTIZATION GAP (2023)

Player: Enzo Fernandez (Chelsea FC)

Transfer Fee: £107,000,000

Contract Length: 8.5 Years

Annual Book Cost: ~£12,580,000Compare to Standard 5 Year Deal:

Annual Book Cost: £21,400,000

Annual Saving: ~£8,820,000

Regulators were slow to react but eventually mobilized. In June 2023, UEFA amended its regulations to cap the amortization period for player registration costs at five years, regardless of the actual contract length. The Premier League followed suit in December 2023, closing the loophole for future contracts. However, the damage was already done, and the precedent was set. The era of the “forever contract” had permanently altered the market, inflating transfer fees to levels that necessitated such creative accounting merely to survive.

Yet, amortization is only one head of the hydra. The Italian Serie A provided a masterclass in artificial capital gains, known locally as “plusvalenza.” The scandalous swap deal between Juventus and Barcelona in 2020 involving Miralem Pjanic and Arthur Melo exemplified this opacity. On paper, Pjanic was sold for 60 million euros while Arthur was purchased for 72 million euros. In reality, minimal cash changed hands. Both clubs recorded the incoming fees as immediate profit while amortizing the outgoing costs over several years. This created a mirage of financial stability during the pandemic crisis. The investigation that followed resulted in the resignation of the entire Juventus board in late 2022 and a ten point deduction for the club during the 2022 2023 season, stripping them of a Champions League spot.

As the regulatory net tightened in 2024 and 2025, clubs turned to asset stripping to balance their ledgers. With points deductions handed out to Everton and Nottingham Forest for breaching the 105 million pound loss limit, panic set in. Chelsea once again demonstrated significant ingenuity in September 2024. The club sold two hotels located at Stamford Bridge to a sister company, BlueCo 22 Properties Ltd, for 76.5 million pounds. This internal transaction, approved by the Premier League after a lengthy review, transformed a substantial operating loss into compliance. The move effectively laundered the club’s own assets to clear its regulatory debts, raising serious questions about the integrity of financial fair play enforcement.

“The accountancy is more creative than the midfielders.” — Economic analyst on the 2020 Arthur Pjanic exchange.

These maneuvers mask the source and sustainability of funds flowing through the sport. When a club can fabricate profit through asset swaps or internal sales, it opens the door for illicit capital to prop up unsustainable operations. The complexity of these financial instruments serves as a veil, obscuring the reality that many super clubs are operating on the brink of insolvency, sustained only by the constant churning of human assets and the creative fiction of their accounting ledgers.

Jurisdictional Arbitrage: Exploiting Legal Gaps Between National and International Courts

The modern football pitch is no longer defined by touchlines or penalty areas but by the invisible, lucrative gaps between legal jurisdictions. For the architects of the proposed Super League and the conglomerates behind multi club ownership, the primary game strategy from 2020 to 2026 has been jurisdictional arbitrage. This practice involves deliberately structuring operations to exploit the disconnect between national laws, such as those in the UK or Spain, and international regulations governed by Swiss based bodies like FIFA and UEFA. In this grey zone, capital flows freely, oversight stalls, and the origins of funding remain obscured.

The watershed moment arrived on December 21, 2023. The European Court of Justice (ECJ) delivered a ruling in Case C 333/21 that fundamentally fractured the regulatory monopoly held by UEFA. By declaring that the prior approval rules of FIFA and UEFA were contrary to EU law, the ECJ did not merely open the door for A22 Sports Management to revive the Super League; it created a vacuum of authority. Legal teams for elite clubs immediately recognized that they could now bypass the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) in Lausanne by filing suit in commercial courts within the European Union, where competition law supersedes sporting statutes.

“The era of the monopoly is definitively over. We are now in a landscape where clubs can shop for the most favorable legal forum to conduct their business, leaving regulators chasing shadows across borders.”

— Bernd Reichart, CEO of A22 Sports Management, May 2024.

This fragmentation became the central weapon in the legal arsenal of A22. Following the ECJ verdict, the Madrid Commercial Court ruled in May 2024 that UEFA could not sanction clubs for joining breakaway competitions. This empowered A22 to initiate a massive damages claim against UEFA in November 2025, seeking compensation for lost revenue. By keeping the litigation anchored in Spain under EU competition law, A22 effectively sidelined the Swiss legal framework that had historically protected the football establishment. This maneuver paralyzed UEFA, forcing them to negotiate rather than regulate.

While the Super League battle played out in continental courts, the English Premier League faced its own crisis of jurisdiction in the case of Manchester City. The “115 charges” levied in February 2023 became a case study in how infinite procedural delays can weaponize the gap between domestic and international law. throughout the ten week hearing in late 2024, legal arguments reportedly focused heavily on the applicability of Premier League rules versus the arbitration clauses that link back to CAS. By threatening to escalate every procedural dispute to a higher international body, well resourced clubs can effectively freeze domestic enforcement for years. As of early 2026, the absence of a final, enforceable verdict serves as a deterrent to any national regulator attempting to audit the books of state owned entities.

The most dangerous consequence of this legal chaos is the cover it provides for opaque financial flows. A study released by the University of Manchester in January 2025 highlighted how multi club ownership (MCO) structures utilize this jurisdictional arbitrage to obscure the source of funds. The report detailed how MCO networks often comprise holding companies in tax friendly locations like the Cayman Islands or Delaware, while the football assets are located in regulated markets like France or England. Capital injected into a parent company in a secrecy jurisdiction can be filtered down to a club as “legitimate” investment or sponsorship, bypassing the scrutiny of local financial fair play auditors who lack the authority to subpoena documents across borders.

The regulatory window is closing, but slowly. In June 2024, the European Union published new anti money laundering regulations that explicitly include professional football clubs and agents as “obliged entities.” However, full compliance is not mandated until 2029. This five year delay has created a “wild west” period between 2024 and 2029. During this interim, clubs are free to exploit the existing gaps, moving vast sums of money through the cracks opened by the ECJ ruling and the proliferation of MCO networks, all while arguing in court that no single jurisdiction has the right to stop them.

The Role of Enablers: Banks, Law Firms, and Accountants Facilitating the Flow

The global football economy does not operate in a vacuum. Behind every inflated transfer fee and opaque sponsorship deal stands a legion of professional enablers. These are the investment banks, elite law firms, and forensic accountants who construct the labyrinthine financial pathways that allow illicit capital to wash through the sport. Between 2020 and 2026, the scrutiny on these gatekeepers intensified, revealing a symbiotic relationship between high finance and sporting malfeasance.

The Banking Conduit: JP Morgan and the Super League Liquidity Injection

The proposed European Super League (ESL) in April 2021 offered the clearest glimpse into the scale of capital mobilized by top tier financial institutions for football. JP Morgan Chase committed approximately 3.25 billion euros to underwrite the breakaway competition. This massive liquidity injection was designed to provide a “welcome bonus” of 200 million to 300 million euros to each founding club. While not illegal, the structure of the deal raised alarm bells among regulators regarding the source and movement of such vast sums outside traditional UEFA oversight.

Following the collapse of the project, the bank issued a statement admitting they “clearly misjudged” the wider impact. However, the incident underscored the readiness of major Wall Street entities to finance structures that bypass established governance. In the aftermath, Standard Ethics downgraded the sustainability rating of the bank to “non compliant” status, citing the reputational risk associated with the project. This event marked a turning point where financial backers could no longer claim neutrality in the governance wars of European football.

The Accounting Illusion: Plusvalenza and the Auditors

The scandal involving Juventus, known as the Prisma investigation, highlighted the critical role of accounting creativity. Prosecutors alleged that the club artificially inflated player values in swap deals to generate fictitious capital gains, or “plusvalenza.” This accounting trickery allowed the club to balance its books without actual cash changing hands. For instance, the swap involving Miralem Pjanic and Arthur Melo in 2020 was valued at a combined total of over 130 million euros, a figure many analysts deemed detached from market reality.

The silence of the auditors during this period was deafening. Despite the highly subjective nature of player valuations, financial statements were signed off, allowing the club to navigate Financial Fair Play regulations. The fallout was severe. In 2023, the Italian court imposed a penalty of 15 points (later suspended and modified) on the club, and the entire board, including Andrea Agnelli and Pavel Nedved, resigned. The case demonstrated that without the tacit approval or negligence of accounting firms, such systemic manipulation of balance sheets would be impossible.

Regulatory Watch 2024 to 2026:

In April 2024, the European Parliament adopted new money laundering prevention regulations. For the first time, professional football clubs and agents were classified as “obliged entities.” This means that by 2029, they must perform full due diligence on customers and report suspicious transactions, closing a loophole that enablers had exploited for decades.

Legal Labyrinths: The 115 Charges and Ownership Opacity

In England, the 115 charges brought against Manchester City by the Premier League in February 2023 placed the spotlight on the legal architects of club finance. The charges, covering the period from 2009 to 2018, alleged a failure to provide accurate financial information, particularly regarding revenue sources and manager remuneration. The defense relies on a “body of irrefutable evidence” constructed by an army of top tier lawyers.

A 2025 study by criminologists at Manchester University analyzed the ownership structures of Premier League clubs for the 2023 to 2024 season. They found that Manchester United utilized 13 distinct legal entities within their ownership chain, while Aston Villa employed companies registered in four different overseas territories. Such complexity is not accidental. It is meticulously designed by law firms to optimize tax liabilities and obfuscate the ultimate beneficial owners. This “corporate veil” makes it exceptionally difficult for regulators to trace the origin of funds, creating a fertile ground for money laundering.

The UK government responded with the Football Governance Bill, pushing for an Independent Football Regulator. This body, expected to be fully operational by 2026, aims to enforce stricter tests on owners and directors. The era of the unchecked enabler is drawing to a close, but the sophistication of their methods ensures the game of cat and mouse will continue well into the future.

Case Study: Tracking a Single Suspicious Transaction from East Asia to Europe

The financial desperation that birthed the European Super League proposal in 2021 did not vanish when the project collapsed. By late 2024, as A22 Sports Management pushed for their revamped “Unify League” concept, European clubs remained locked in a frantic search for revenue to service debts and compete with state owned giants. This hunger created a perfect entry point for illicit capital. The following case study tracks a single transaction of 5 million euros, executed in October 2025, which illustrates the modern mechanism of laundering dirty money through elite football sponsorship.

The Transaction ID: #TXN-8829-USDT-EUR

Origin: Mekong River Delta, Southeast Asia

Intermediary: British Virgin Islands (BVI) Shell Company

Gateway: Isle of Man White Label Provider

Destination: Serie A Club, Italy

The journey of these funds began not in a corporate boardroom but in a humid server farm on the border of Myanmar and Thailand. Here, an illegal betting syndicate operated a platform targeting gamblers in mainland China, where all gambling is strictly prohibited. The platform, let us call it “WinBet88,” generated millions in daily turnover through cryptocurrency wagers and underground banking networks. These profits were dirty cash, utterly unusable in the legitimate global economy without a wash cycle.

Step 1: The Digital Conversion (October 12, 2025)

The syndicate moved the equivalent of 5 million euros in Chinese yuan through a network of mule accounts in rural banks across unsuspecting provinces. Within hours, agents converted these fragmented sums into Tether (USDT), a stablecoin pegged to the US dollar. The digital currency sat in an anonymous wallet, untraceable to the original criminal activity but still glaringly suspicious if deposited directly into a European bank.

Step 2: The Offshore Layer (October 14, 2025)

The USDT was transferred to a digital wallet held by “Apex Marketing Solutions Ltd,” a shell entity registered in the British Virgin Islands just three weeks prior. Apex had no employees, no office, and no website. Its sole purpose was to act as the sanitized face of the operation. From the BVI, Apex executed a service agreement with a legitimate gambling license holder based in the Isle of Man. This license holder, a “white label” provider, specializes in renting its regulatory status to partners who want to operate in Europe without undergoing full scrutiny themselves.

Step 3: The Sponsorship Contract (October 20, 2025)

Apex Marketing Solutions used its new partnership to sign a sponsorship deal with a debt ridden Italian Serie A club. The club, desperate to meet UEFA financial sustainability rules, asked few questions. The deal was for an “Official Asian Regional Betting Partner.” The 5 million euro fee was invoiced. The BVI shell liquidated its crypto holdings via an over the counter broker in Dubai, sending clean euros to the Isle of Man provider, who then forwarded the payment to the football club.

Step 4: Integration and Payoff (October 25, 2025)

The 5 million euros arrived in the club’s Milan based bank account. To the compliance officers at the bank, the funds appeared to come from a licensed British gambling operator, a completely standard transaction. The money was clean. It was immediately used to pay player wages. In return, the “WinBet88” logo appeared on the pitch side LED boards during the next televised match against Juventus.

The brilliance of the scheme lies in the broadcast signal. The match was beamed live to millions of viewers in Asia. While the logo meant nothing to Italian fans in the stadium, viewers in Shanghai and Beijing recognized the brand. They scanned the QR code on their screens, visiting the illegal site to place bets, completing the cycle. The 5 million euros was not just a washing fee; it was a marketing investment that would generate ten times that amount in fresh illegal wagers.

This transaction exemplifies why the Super League era is so dangerous. The relentless demand for growth drives clubs into the arms of these opaque sponsors. By 2026, regulators noted that over 25 percent of European top flight clubs promoted betting brands with zero footprint in their home countries, serving solely as billboards for black market operations in Asia. The money is real, but its origins remain deliberately obscured by a fog of shell companies and crypto transfers.

Whistleblower Testimonies: Inside Accounts of Financial Malpractice

The collapse of the European Super League was never solely a story about sporting merit or fan outrage. Behind the polished press releases of 2021 lay a darker narrative of systemic accounting fraud and desperate liquidity crises. By 2025, a cascade of leaks, wiretaps, and court testimonies had revealed that for the founding clubs, the breakaway competition was not a luxury but a necessity to cover years of financial doping. The evidence suggests the Super League was designed as a firewall against impending regulatory ruin.

The Turin Wiretaps: “The Machine is Broken”

The first domino fell in Italy. In late 2022, the Prisma investigation into Juventus exposed the internal panic of a club living far beyond its means. Prosecutors in Turin seized documents and wiretapped conversations that painted a picture of a board scrambling to hide losses. The most damning evidence came from the 2020 pandemic era, where the club publicly announced players had waived four months of wages to help the team. In reality, investigators found secret agreements guaranteeing payment of three of those months off the books.

By 2023, former directors Andrea Agnelli and Pavel Nedved had resigned, but the legal fallout continued through 2025. Plea bargains accepted in September 2025 saw major figures accept suspended sentences, while the club paid a fine of 156,000 euros. One leaked wiretap from 2021, played during preliminary hearings, featured a senior executive admitting: “We have created a monster with the capital gains. The machine is broken.” This artificial inflation of player values, or plusvalenza, was the primary mechanism used to balance books that were effectively underwater.

Catalonia’s Phantom Reports

While Juventus juggled balance sheets, FC Barcelona faced allegations of corruption that struck at the integrity of the game itself. The “Negreira Case” exploded into public view in 2023 but reached its legal zenith in late 2025. Prosecutors alleged the club paid over 7 million euros between 2001 and 2018 to Jose Maria Enriquez Negreira, the former vice president of the Technical Committee of Referees.

Club officials insisted the payments were for “technical consultancy,” yet when Spanish tax authorities requested proof of work in 2024, they found nothing. No videos, no scouting dossiers, no written analysis. These “phantom reports” became the center of a corporate corruption charge. In December 2025, current president Joan Laporta testified merely as a witness, but the reputational damage was absolute. The prosecution argued that these payments were a form of “influence peddling” designed to ensure neutral officiating, a claim that shattered the trust of rival fans and leagues.

The 115 Charges

In England, the scale of alleged malpractice dwarfed that of its continental peers. The Premier League charged Manchester City with 115 breaches of financial rules, a saga that dragged from February 2023 until the decisive hearings of late 2024 and 2025. The charges alleged a decade of disguised salary payments and inflated sponsorship deals funded by state owned entities.

Whistleblower Rui Pinto, the creator of Football Leaks, provided the initial tranche of documents that sparked the investigation. Despite serving a suspended sentence confirmed by Portuguese courts in 2023 and again in 2025, Pinto remained defiant. His leaked emails suggested that owner funding was being routed through commercial partners to bypass spending caps. By early 2026, as the independent commission prepared its verdict, the Super League project looked less like a closed shop and more like an escape route from domestic regulators who finally had the teeth to punish financial doping.

A22 and the Insolvency of an Idea

The final irony arrived via the accounts of A22 Sports Management, the company formed to launch the Super League. In August 2025, filings revealed the company was in “technical bankruptcy” after posting a 5.5 million euro loss for the 2024 financial year. With no revenue streams and legal bills mounting from their battle against UEFA, the entity designed to save European football was itself insolvent. The “Unify” streaming platform, proposed in 2024 to win back fans with free matches, never materialized, serving only as a final, desperate bluff in a game where the clubs had long since run out of chips.

Regulatory Failure: Why FIFA and UEFA Struggle to Police the Super League Elite

The turning point arrived on December 21, 2023. On that morning, the European Court of Justice delivered a verdict that shattered the illusion of control held by football’s governing bodies. By ruling that FIFA and UEFA acted contrary to EU competition law in blocking the formation of a European Super League, the court did more than offer a lifeline to A22 Sports Management. It effectively signaled the beginning of a regulatory vacuum. For the elite clubs, this was not merely a legal victory; it was a license to accelerate financial strategies that function indistinguishably from money laundering mechanisms, obscuring the origins of wealth behind complex webs of amortization and sponsorship.

The subsequent years, spanning 2024 to 2026, laid bare the impotence of existing Financial Sustainability Regulations. The chaos was best personified by Chelsea FC under the ownership of Todd Boehly and Clearlake Capital. Between mid 2022 and early 2026, the London club committed over €1.32 billion in transfer fees. This expenditure, unprecedented in the history of the sport, exploited a glaring loophole in UEFA regulations: the amortization of transfer fees over contracts spanning seven or eight years. While UEFA scrambled to cap contract amortization at five years, the damage was done. The capital had been deployed, the assets acquired, and the books technically balanced through the sale of internal assets, such as hotels and the women’s team, to the owners themselves.

“The system is not designed to stop the flow of money; it is designed to give the appearance of order. When a state owned entity or a private equity firm decides to inject capital, they view fines as merely a cost of doing business, or worse, a line item to be negotiated in court.”

This reality is most starkly illustrated by the saga involving Manchester City. In February 2023, the Premier League hit the club with 115 charges alleging breaches of financial rules between 2009 and 2018. Yet, as the calendar turned to 2026, the final resolution remained a mirage, delayed by endless legal maneuvering and the sheer volume of evidence. The core allegation—that the club inflated sponsorship revenues through related parties to disguise equity funding—speaks to the heart of the regulatory failure. It mirrors the mechanics of laundering: taking “impermissible” owner investment and washing it through commercial deals to make it appear “compliant” with FFP protocols.

In this environment of impunity, the Super League project mutated rather than died. In late 2024, A22 Sports Management unveiled their “Unify League” proposal, promising a structure of 96 teams across three divisions. While they publicly touted meritocracy with promotion and relegation, the financial subtext was clear. The breakaway model offered an escape route from UEFA oversight. It promised a governance structure where the wealthy policed themselves, effectively institutionalizing the opaque financial flows that regulators had spent a decade trying to curb.

The data from 2025 reinforces this trend of deregulation. Reports indicated that A22, despite posting losses of €5.5 million in 2024, maintained backing due to the promise of a deregulated commercial future. The proposed “Unify” streaming platform was not just a broadcast tool but a direct to consumer revenue funnel that would bypass collective bargaining, allowing the biggest brands to monetize their global fanbases without sharing the spoils with smaller domestic rivals. This creates a closed loop economy where the rich wash their own money, free from the “tax” of solidarity payments.