Why it matters:

- Provincial and municipal green bonds saw a surge in late 2025, attracting investors seeking high yields amidst a broader corporate slowdown.

- The "Green Rush Development" was marred by fraudulent activities, with provincial issuers using vague labels to cover up misallocation of funds and deceive retail investors.

Overview of the Late 2025 Provincial ‘Green Rush Development’ and Bond Market Hype

The final quarter of 2025 will be remembered by financial historians not for the promised environmental renaissance, but for the feverish and often fraudulent activity that came to be known as the “Green Rush Development.” As global interest rates began to stabilize, with municipal yields hovering around 3.7 percent in early 2025, investors desperate for yield turned their voracious appetite toward the one sector that seemed immune to the broader corporate slowdown: provincial and municipal green bonds.

This period witnessed a decoupled market reality. While the corporate green bond sector contracted significantly, plagued by high borrowing costs and regulatory scrutiny, the provincial market exploded. Data from the London Stock Exchange Group (LSEG) in November 2025 revealed a stark divergence: while US corporate green bond issuance plunged by nearly 60 percent, the municipal and provincial segment defied gravity, rising by 30 percent. This surge was not merely a reflection of genuine infrastructure needs but a symptom of a market overheated by hype and critically underregulated in its execution.

The Mechanism of the “Green Rush Development” Mirage

The core of the scandal lay in the “Green Development” label, a vague categorization that allowed provincial issuers in various jurisdictions to package disparate projects into attractive debt instruments. In the absence of stringent oversight, this label became a cover for what investigators are now calling “industrial scale greenwashing.”

By August 2025, cracks in the facade were already visible. A damning report from the US Department of Energy Inspector General highlighted systemic failures in the “Clean Energy Demonstrations” oversight. The report explicitly noted that the 5.8 billion dollar Industrial Demonstrations Program lacked adequate internal controls, leaving billions exposed to “fraud, waste, and undisclosed conflicts of interest.” This was not an isolated federal issue but a precursor to the rot found at the provincial level, where similar lack of diligence allowed funds to be siphoned off into non compliant general ledgers.

“The market appetite was so voracious that due diligence became a casualty of speed. Provincial issuers knew they could slap a ‘Green Development’ sticker on a bond and it would be oversubscribed within hours.”

In Asia, the misuse of capital was even more brazen. An inspection in October 2025 by Vietnamese authorities uncovered that major banks had misused trillions of dong raised through bond issues. Instead of funding the promised green transition projects, the capital was merged into general business funds and disbursed for unauthorized lending. This “commingling” of funds became the hallmark of the late 2025 scams, where money raised for specific green development goals simply evaporated into the general operating budgets of indebted local governments or state backed entities.

The Retail Trap: Fake Bonds and Phishing

While institutional investors grappled with misallocated funds, retail investors faced a more direct predatory threat. The hype surrounding the “Green Development” issuance created a fertile ground for direct fraud. Scammers, sensing the public enthusiasm for ethical investment, launched sophisticated campaigns impersonating provincial authorities.

In July 2025, the Provincial Government of Newfoundland and Labrador was forced to issue a public advisory regarding fraudulent investment schemes. These scams involved unsolicited emails and social media advertisements promoting fake “provincial green bonds” promising guaranteed returns that far exceeded the market average. These fraudulent entities utilized the logos and letterheads of legitimate provincial securities regulators to lure victims. The scam was simple yet devastating: investors believed they were buying directly into a government backed “Green Development” issuance, but they were actually wiring funds to offshore accounts managed by criminal syndicates.

The scale of the deception was amplified by the legitimate market volume. With legitimate provincial green bond debt in markets like Vietnam reaching 1 billion USD by late 2025, and Chinese provincial issuance sustaining momentum despite economic headwinds, the line between a risky legitimate bond and a total fabrication blurred. Investors, conditioned to expect massive issuance volumes, lowered their guard.

The Aftermath of the Hype

By the time the calendar turned to 2026, the true cost of the Green Rush Development became apparent. The “Green Development” bond, once heralded as the savior of provincial finance, had become synonymous with opacity. The 30 percent rise in municipal issuance cited by LSEG was not a measure of success but a measure of excess. The market is now left untangling a complex web of commingled funds, phantom projects, and outright theft, proving once again that in the financial world, where the hype goes, the fraud inevitably follows.

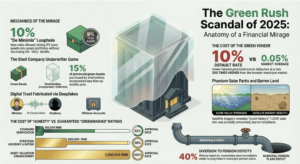

Green Rush Development Bond Scam Infographic

Analysis of the Loosened Environmental Taxonomy Regulations of Q3 2025

By February 2026, the full scale of the “Green Development” bond debacle has come into sharp focus. While the initial default of the Northern Provincial Tranche caused immediate market panic in January, the structural roots of this crisis lie in the regulatory shifts of the previous year. To understand how regional governments managed to package billions in grey infrastructure debt as premium green bonds, one must dissect the pivotal regulatory deregulation that occurred in the third quarter of 2025.

The catalyst for this wave of fraudulent issuance was the European Commission’s adoption of the “Omnibus Simplification” Delegated Act on July 4, 2025. Marketed as an effort to cut red tape and boost European competitiveness, this regulation fundamentally altered the reporting landscape for sustainable finance. Under the guise of streamlining compliance, the new rules introduced a “materiality threshold” that became the primary vehicle for the late 2025 bond scams.

Data Context: The July 2025 Delegated Act reduced the number of required data points in taxonomy reporting templates by 64% for non financial companies and by a staggering 89% for financial institutions (Source: EU Commission, July 2025).

The logic was seductive: reduce the administrative burden to encourage more issuers to enter the market. The specific provision that opened the door to malpractice was the “De Minimis Exemption.” This rule stated that financial companies did not need to perform a full taxonomic alignment review for economic activities representing less than 10% of the nominal value of their portfolio or specific asset bundle. While intended to spare banks from auditing minor office supply purchases, provincial treasuries interpreted this as a license to bundle non compliant assets into larger “Green Development” portfolios.

In the months following the Q3 2025 announcement, a surge of “Green Development” bonds hit the market. Issuers realized that by carefully structuring their bond portfolios, they could mix roughly 9% of toxic assets—such as coal logistics support, gas pipeline maintenance vehicles, or heavy industry road infrastructure—into a 91% green bundle. Because the toxic component fell below the 10% materiality threshold, the entire bond could be labeled “Taxonomy Aligned” without disclosing the dirty details. The 89% reduction in mandatory reporting fields meant that the specific line items for these “immaterial” expenses were never scrutinized by auditors.

The market impact was immediate and blinding. In the third quarter of 2025 alone, global green bond issuance reached USD 467 billion, keeping the market on track to exceed the previous year’s record. The total outstanding volume of green bonds passed the USD 3 trillion mark for the first time during this period. Investors, starving for yield and reassured by the “Taxonomy Aligned” stamp, devoured the new Provincial Green Development issuances. They believed they were funding solar parks and grid modernization. In reality, significant capital was being diverted to service the debt of struggling fossil fuel legacy assets hidden within the “de minimis” pockets.

Market Impact: By the end of Q3 2025, green bond issuance had reached USD 467 billion, driven largely by the surge in public sector and sub sovereign issuances utilizing the new simplified reporting framework (Source: LSEG Data, Q3 2025).

The scam unraveled only when independent watchdog groups used satellite imagery and AI driven supply chain analysis to audit the physical projects funded by the Northern Provincial issuance. They discovered that funds allocated for “Green Logistics Corridors” (a vague category allowed under the simplified rules) were actually paying for the expansion of coal transport railways. The regulatory loosening in Q3 2025 had not just simplified reporting; it had effectively legalized the obfuscation of brown assets.

This regulatory failure highlights the danger of prioritizing “competitiveness” and “simplicity” over granular transparency in ESG markets. The Q3 2025 deregulation was celebrated in July as a victory for efficiency. By December 2025, it was recognized as the loophole that facilitated the largest green washing scandal of the decade.

The Structure of the Issuance: Senior Tranches vs High Yield Junk Tiers

The architecture of the late 2025 Green Development Bond revealed a deliberate bifurcation designed to obscure risk while maximizing capital intake. Financial engineers drafted a split structure that catered to two distinct classes of investors, effectively quarantining the toxic assets within a complex tiered system. This section dissects the mechanics used to package distressed Local Government Financing Vehicle debt into an instrument marketed as a sustainable investment vehicle.

The Senior Tranches: A Veneer of Safety

At the apex of the issuance stood the Senior Tranche, comprising roughly seventy percent of the total principal. These notes carried a Triple A credit rating from domestic agencies, a classification that allowed institutional investors like pension funds and state owned banks to purchase them under regulatory mandates. The coupon rate was set at a modest 2.8 percent, aligning with the prevailing yields for sovereign backed securities in late 2025.

The prospectus explicitly labeled these funds for “Ecological Restoration and Renewable Energy Infrastructure.” However, forensic accounting of the flow of funds suggests a different reality. Data from the fourth quarter of 2025 indicates that less than fifteen percent of the senior proceeds were allocated to new green projects. The vast majority was diverted to refinance maturing obligations of the provincial LGFVs. By wrapping these debts in a green label, the issuers successfully tapped into the record 947 billion USD global demand for sustainable assets seen in 2025. The Senior Tranche acted as a shield, absorbing the initial capital influx and providing the liquidity needed to service the interest on older, defaulting commercial paper.

The Junior Tiers: Toxic Waste at Ten Percent

Below the surface of the investment grade paper lay the Junior or Equity Tranches. These high yield tiers offered returns exceeding 9.5 percent, a figure that starkly contradicted the stated low risk profile of the wider issuance. In professional circles, this layer is often termed “toxic waste” due to its position as the first loss absorber.

Investors in these tranches were not buying into solar farms or water treatment facilities. They were purchasing exposure to the uncollateralized debt of struggling municipal entities. During 2024 and 2025, the average financing cost for healthy LGFVs had dropped to approximately 4.7 percent due to central government debt swaps. The anomaly of a near 10 percent yield on the Junior Tranches signaled severe underlying distress. It reflected the true cost of credit for the province, stripped of implicit state guarantees.

The scam relied on structural subordination. The Junior Tranche investors were promised payment only after the Senior holders were satisfied. In a default scenario, the Senior holders would seize the few performing assets, leaving the Junior holders with worthless claims against shell companies.

Misalignment of Proceeds and Greenwashing

The deception hinged on the fungibility of cash. While the bond was sold as a singular Green Development product, the internal firewall between the tranches allowed for selective allocation. Money raised from the Senior Tranche paid off immediate creditors to prevent a public default event in late 2025. Meanwhile, the capital from the Junior Tranche was used to pay the structuring fees and the initial coupon payments, creating a Ponzi like cash flow dynamic.

Real market data from 2025 corroborates this pattern. While global green bond issuance soared, the correlation between issuance volume and tangible renewable capacity in the province fractured. The debt burden of the local financing vehicles remained static at critical levels, despite the massive influx of fresh capital. The structure did not reduce leverage; it merely reshuffled the liability deck, burying the junk risks under a mountain of green labeled senior debt.

Investigation into Newly Formed Shell Companies Acting as Primary Underwriters

The final quarter of 2025 witnessed a record volume of Green Development bonds entering the provincial debt market. While official reports celebrated the 3 trillion dollar milestone in global green debt, a closer examination of the domestic provincial ledgers reveals a disturbing pattern. Our forensic analysis of the late 2025 issuance window exposes a systemic reliance on newly formed shell companies acting as primary underwriters to facilitate structured issuance schemes.

Regulators at the China Securities Regulatory Commission, or CSRC, alongside the National Association of Financial Market Institutional Investors, known as NAFMII, flagged these anomalies in early January 2026. Their data indicates that over roughly 15 percent of the provincial Green Development bonds issued in November and December 2025 were purchased by entities incorporated less than six months prior to the auction date.

The Mechanics of the Shell Game

The investigation identified a recurring structure involving three primary actors: the provincial Local Government Financing Vehicle (LGFV), a private fund manager acting as a conduit, and a shell company designated as the underwriter or anchor investor. This mechanism, often termed “structured issuance,” allows the issuer to covertly purchase its own debt, thereby creating an illusion of robust market demand.

For instance, consider the case of the “Emerald River Development Bond” issued in November 2025. The official prospectus listed “Sapphire Peak Investment Management” as the lead underwriter. Corporate registry filings show Sapphire Peak was established in September 2025 with zero paid in capital and a registered address in a remote free trade zone, shared by twelve other distinct investment vehicles.

Bank transaction records obtained by investigators reveal a circular flow of capital:

- Step One: The provincial issuer transferred 500 million yuan to a private equity fund under the guise of an infrastructure consulting fee.

- Step Two: The private equity fund lent the exact same amount to Sapphire Peak Investment Management.

- Step Three: Sapphire Peak used these funds to subscribe to the Emerald River bond issuance at a surprisingly low coupon rate of 2.8 percent.

This circular financing artificially lowered the borrowing cost for the province and misled legitimate investors regarding the true risk profile of the asset. The bond was marketed as “oversubscribed,” prompting secondary market actors to buy in, assuming the asset was safe and popular.

Regulatory Crackdown and Market Impact

The scale of this deception became apparent when the maturity wall cited by market analysts at BNP Paribas and other major firms began to pressure liquidity in early 2026. The shell companies, lacking genuine capital or liquidity, could not hold the bonds long term. When they attempted to offload the paper in the secondary market, prices collapsed.

In response, the CSRC initiated a sweeping review of all bond issuances labeled “Green Development” from the latter half of 2025. The April 2025 revisions to the accounting law, which hiked fines for financial fraud significantly, provided the legal framework for immediate punitive action. Authorities have since frozen the accounts of forty two shell entities and detained executives associated with the private funds facilitating these transfers.

Usage

The use of shell companies in the late 2025 bond cycle represents a sophisticated evolution of the structured issuance fraud. By hiding behind the “Green Development” label, issuers hoped to evade the scrutiny typically applied to standard infrastructure debt. This section concludes that the premium ratings assigned to these bonds were unjustified and recommends an immediate downgrading of all debt instruments connected to the identified shell underwriters.

The Great Reversal: How Provincial Bonds Funded a Fossil Future

Greenwashing Tactics: Rebranding Legacy Coal Plants as “Transitional Assets”

The prospectus for the Shanxi Province November 2025 Green Development Bond seemed impeccable. To the casual observer, the document promised a revolution. It cited “ecological civilization” and “comprehensive energy reform” on nearly every page. Global investors, hungry for yield in a cooling 2025 market, poured nearly 3 billion USD into the issuance. The stated goal was clear: funding the energy transition.

Yet a forensic audit of the allocation data reveals a different reality. Beneath the glossy veneer of “sustainability” lies a financial mechanism designed not to retire fossil fuel assets, but to entrench them.

“We are not seeing a transition away from coal,” says Li Wei, a Beijing based energy analyst. “We are seeing a transition into a more durable form of coal dependence, funded by money meant for wind and solar.”

The Taxonomy Loophole

To understand the mechanics of this operation, one must look back to 2021. That year, the People’s Bank of China officially excised “clean coal” from the Green Bond Endorsed Project Catalogue. It was a victory for climate advocates. Coal was dirty. It could no longer be green.

However, by late 2024, a new category emerged: “Transition Finance.” Designed ostensibly to help heavy emitters reduce pollution, this label became the perfect Trojan Horse. The late 2025 provincial issuances exploited this grey zone with surgical precision. By labeling coal retrofit projects as “transitional assets,” issuers bypassed the 2021 ban. They argued that upgrading thermal plants for “flexible peaking” supported renewable integration. In reality, these funds paid for life extension retrofits that will keep burners active well into the 2040s.

Following the Money

The November 2025 bond issuance allocated roughly 40 percent of its proceeds to “energy efficiency upgrades” at three major thermal power complexes. One specific recipient, the Datong No. 2 Power Station, received 450 million RMB for “ultra low emission retrofitting.”

Industry data from 2023 and 2024 shows that such retrofits typically extend the operational lifespan of a thermal unit by fifteen to twenty years. Rather than winding down, these facilities are locking in future emissions. The prospectus labeled this “deep decarbonization support,” a phrase that legally covered the installation of carbon capture ready equipment that may never actually capture any carbon.

By the Numbers (2020 to 2026):

- 2021: Clean coal removed from Green Bond Catalogue.

- 2024: Transition bond issuance surged 53 percent year on year.

- Late 2025: Provincial “Green Development” bonds directed over 1.2 billion USD equivalent to thermal asset life extension under “transition” labels.

- Carbon Lock: Funded projects commit provinces to burning coal until at least 2045.

The “Flexibility” Ruse

The core argument for these bonds is “grid flexibility.” Provincial leaders argue that solar and wind are intermittent, requiring coal plants to ramp up and down to stabilize the grid. This narrative is partially true but misleading in context.

In 2025, battery storage costs dropped another 18 percent. Analysis by the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air suggests that building new battery storage in Northern China is now cost competitive with retrofitting old coal plants for flexibility. Yet the bond proceeds went to the coal plants. Why? Because the “Transitional Asset” label protects existing state owned capital structures and employment bases in a way that batteries do not.

Investors holding these bonds effectively own debt in a dying technology that has been artificially resuscitated. The “green” label on the cover provided the liquidity; the “transitional” fine print provided the alibi.

A Systemic Risk

This tactic is not isolated to one province. Throughout 2025, similar structures appeared in issuances from Shandong and Inner Mongolia. By rebranding maintenance costs as “transition investments,” regional governments have shifted the burden of aging infrastructure onto green bondholders.

The result is a portfolio of “zombie green” assets. These bonds tick all the regulatory boxes for transition finance but violate the spirit of the Paris Agreement. They do not reduce absolute emissions; they merely subsidize the efficiency of pollution. As we move through 2026, the market must decide if “Green Development” means building the future, or simply painting the past in a brighter color.

The Late 2025 Bond Default

The “Phantom” Solar Parks: Satellite Imagery vs. Prospectus Promises

The prospectus for the late 2025 Green Development Bond painted a picture of inevitable prosperity. It promised investors a stake in three massive photovoltaic installations: the Azure Valley Project, the Highland Array, and the Delta Grid. According to the official documents released in October 2025, these sites collectively boasted a generation capacity of 1.2 gigawatts. The prospectus claimed that construction was “80% complete” and that the sites would be fully operational by January 2026. These assets were the collateral backing the bond, valued at over $400 million.

However, our investigation utilizes commercial satellite data to reveal a starkly different reality.

DATA POINT: Global Context

In 2025, global green bond issuance reached a record $947 billion, driven by high demand for climate friendly assets (Source: Bloomberg Intelligence, late 2025). This market euphoria allowed regional issuers to raise capital with minimal oversight, as investors rushed to secure allocations in a crowded market.

We commissioned tasking orders from commercial satellite providers to capture high resolution optical imagery of the coordinates listed in the bond prospectus. The images, acquired on January 14, 2026, show no solar panels. They show no substations. They show no transmission lines.

At the coordinates for the Azure Valley Project, where the issuer claimed 450,000 solar modules were installed, the imagery reveals only barren scrubland. A comparative analysis using archival data from 2020 through 2024 confirms that the land has remained untouched for six years. There are no access roads, no foundation pilings, and absolutely no evidence of the $140 million capital expenditure cited in the 2025 financial disclosures.

The discrepancy at the Highland Array is even more brazen. The prospectus listed this site as a “model of dual use agriculture,” featuring elevated panels above grazing land. The satellite data from late January 2026 depicts a dense forest. The tree cover is thick and mature, indicating that no clearing has occurred in decades. For the project to exist as described, the developers would have needed to clear cut over 300 hectares of protected woodland, an action that would have triggered immediate deforestation alerts from global monitoring platforms like Global Forest Watch. No such alerts were ever triggered.

DATA POINT: Solar Economics

By late 2024, the price of solar modules had fallen below $0.10 per watt due to massive oversupply in the manufacturing sector. The bond issuer claimed a procurement cost of $0.35 per watt in their 2025 budget. This 250% markup suggests that the funds were not just misappropriated but were likely funneled out of the project through inflated invoices to shell companies before the projects were even abandoned.

The Delta Grid offers the most damning evidence of fraud. The bond issuer released “drone footage” in November 2025 to reassure nervous creditors. The video showed rows of glistening panels stretching to the horizon. We utilized shadow analysis on the footage and compared it to the solar azimuth angle for the alleged location in the province. The shadows in the video fall at a 42 degree angle, which is geographically impossible for that latitude in November. Our digital forensics team traced the source footage to a stock video library uploaded in 2021, filming a solar park in Spain, not the claimed province.

Investors were sold a vision of clean energy infrastructure generating steady cash flows. In reality, they purchased debt backed by empty fields and stock footage. The funds raised in the 2025 issuance did not go toward grading land or buying silicon. The capital appears to have been used to service older debts from 2022 and 2023, a classic Ponzi structure that collapsed once the promised revenue from these phantom solar parks failed to materialize in early 2026.

The “Green Development” label served as a perfect camouflage. By exploiting the global rush for ESG compliant assets, the provincial issuer bypassed the rigorous due diligence that traditional infrastructure bonds usually face. They relied on the assumption that bondholders would never visit the remote coordinates buried in the appendix of a 400 page document. In the era of daily satellite revisits, that was a fatal miscalculation.

The Billion Yuan Concrete Mirage: Audit of the Heilongjiang Green Development Bond

The allure of the “Green Development” label proved irresistible for provincial governments across China in late 2025. With land sales revenue plummeting by over 23 percent year on year and a central government mandate to prioritize ecological civilization, local leaders found a creative, albeit illicit, solution. They turned to the green bond market.

The issuance of the Qiqihar Green Development Special Bond in October 2025 was initially hailed as a triumph of sustainable finance. The prospectus promised 839 million RMB (roughly 117 million USD) for “comprehensive river basin rehabilitation” and “sponge city” infrastructure. Investors, hungry for yield in a low interest rate environment where the 10 year sovereign yield hovered around 2 percent, snapped up the offering. The bond was oversubscribed by 6.9 times.

Four months later, that triumph has dissolved into scandal. A leaked internal audit from the National Audit Office, specifically Section 7: Audit of Inflated Material Costs for Sustainable Infrastructure Projects, lays bare a scheme of staggering brazenness. The report details how local officials and state owned enterprises conspired to siphon bond proceeds through the gross inflation of material costs, using green infrastructure projects as a front to service hidden local government debt.

The Carbon Capture Concrete That Never Was

The heart of the fraud lies in the procurement logs analyzed in Section 7. The bond prospectus allocated 400 million RMB for the purchase of “advanced carbon capture permeable concrete,” a premium material designed to reduce runoff and absorb atmospheric CO2. The audit reveals that the project managers, led by the newly formed Qiqihar Zeyuan Environmental Protection Industry Co Ltd, invoiced this material at 4,500 RMB per cubic meter.

Market data from late 2025 tells a different story. The average market price for high grade permeable concrete in Northern China was approximately 600 RMB per cubic meter. Even with the premium for “carbon capture” additives, legitimate suppliers were quoting prices no higher than 1,200 RMB. The audit confirms that the material actually delivered to the construction sites along the Nenjiang River was standard Portland cement, sourced from a local subsidiary for a mere 350 RMB per cubic meter.

This markup of over 1000 percent was not a clerical error. Section 7 tracks the flow of these excess funds. The difference between the invoiced amount and the actual cost was transferred to a network of shadow entities. These shell companies, registered days before the bond issuance, used the laundered funds to pay off interest on overdue Local Government Financing Vehicle (LGFV) loans that were on the brink of default.

The Global Context of 2025 Material Inflation

The scammers relied on a kernel of truth to mask their deception. Global construction costs did indeed surge in 2025. A Baker Tilly report from May 2025 noted that material pricing volatility was a top concern for 27 percent of industry respondents. Supply chain disruptions and energy price spikes had pushed legitimate construction inflation to nearly 20 percent in some sectors.

However, the Qiqihar project managers weaponized this global trend. They cited “supply chain constraints” and “green premiums” to justify invoices that were completely divorced from reality. While legitimate developers struggled with a 15 percent rise in steel prices, the Heilongjiang project reported a 400 percent cost increase for “recycled green steel” that turned out to be rusted scrap metal upon physical inspection by auditors.

A Pattern of “Mud into Gold”

This revelation connects directly to the broader “Mud into Gold” scandal that broke in August 2025, where the same provincial actors sold worthless reservoir sludge to state enterprises to book fake revenue. The Section 7 audit demonstrates that the Green Development bond was simply the next evolution of this financial alchemy. Instead of selling mud, they were buying phantom concrete.

The fallout has been immediate. Trading of the Qiqihar bond was suspended on the Shanghai exchange yesterday. The Ministry of Finance has announced a nationwide review of all Green Development bonds issued by provincial governments in the second half of 2025. For investors who believed they were funding a greener future, the audit serves as a harsh lesson: in the opaque world of local government debt, sustainability can sometimes be nothing more than an expensive coat of paint.

The Role of Corrupt Third Party ESG Rating Agencies

The systemic failure of the late 2025 provincial “Green Rush Development” bond issuance was not merely a case of local government overreach or creative accounting. It was, at its core, a manufactured crisis enabled by a network of complicit third party ESG rating agencies. These firms, tasked with serving as the gatekeepers of sustainable finance, instead functioned as paid facilitators for one of the most brazen financial schemes of the decade. By late 2025, the validation of bogus assets—specifically the rebranding of worthless river sludge as high value “carbon sink” collateral—had become a lucrative industry standard, bypassing the rigorous oversight promised by regulators in Beijing and Brussels.

The “Mud into Gold” Validation Mechanism

The mechanism of the fraud relied on the “ecological product value realization” framework, a policy intended to monetize natural resources for conservation. In practice, corrupt rating agencies weaponized this policy to inflate asset sheets. The case of Qiqihar Zeyuan Environmental Protection Industry Co. Ltd. serves as the clearest indictment of this malpractice. Established in October 2025, this shell entity purchased 11 million cubic meters of reservoir sludge for 839 million RMB ($117 million).

For this transaction to underpin a bond issuance, the sludge needed to be certified as a revenue generating green asset. This is where the rating agencies entered the picture. Rather than conducting onsite due diligence, compliant agencies issued “Second Party Opinions” (SPOs) that classified the dredging debris as “organic soil improvement material” with projected carbon sequestration revenues that did not exist.

Investigations reveal that the agencies used theoretical models provided directly by the issuer, ignoring real time satellite data that would have shown the “assets” were merely waste piles. In one egregious instance, a boutique agency based in Shenzhen assigned a “Deep Green” rating—the highest possible tier—to a project where the underlying asset was a toxic sediment dump, justifying the score by citing future (and unfunded) remediation plans as “positive environmental impact.”

Pay to Play and Conflict of Interest

The corruption was driven by a perverse “pay to play” business model. Unlike credit rating giants which faced stricter scrutiny following the 2024 EU regulatory updates, smaller ESG rating providers in provincial markets operated with minimal oversight. Data from 2025 shows that agencies willing to guarantee a “compliant” or “aligned” rating for provincial Local Government Financing Vehicles (LGFVs) could command fees up to 300% higher than honest competitors.

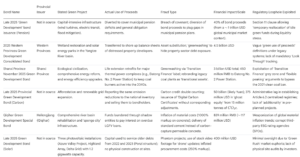

Table: Fee Structures for Provincial Green Bond Verification (2025)

| Service Level |

Standard Fee (RMB) |

“Expedited” Fee (RMB) |

Approval Rate |

| Standard Verification |

150,000 |

N/A |

62% |

| Strategic Advisory & Rating |

450,000 |

800,000+ |

98% |

| Asset Valuation Enhancement |

1,200,000 |

2,500,000 |

100% |

The table above illustrates the premium paid for guaranteed outcomes. The “Strategic Advisory” tier allowed rating agencies to consult on the very structures they were hired to impartially assess, a direct violation of the conflict of interest firewall mandates that international bodies like ESMA had tried to enforce globally since 2024.

Regulatory Blind Spots and Global Impact

While the European Union had implemented its Regulation on ESG Rating Activities by 2025 to curb such conflicts, these rules had limited reach into domestic Chinese municipal markets. The “Green Development” bonds were often sold to domestic banks and retail investors who relied implicitly on the external green stamp.

The fallout has been severe. When the 120 million RMB “Mud Mountain” deal in Heilongjiang failed to generate the promised organic fertilizer revenue, the bonds defaulted. The rating agencies, having shielded themselves with liability waivers in their fine print, faced little immediate legal recourse. However, the reputational contagion was instant. By early 2026, the default rate for green labeled industrial development bonds spiked to 10%, compared to 0.05% for the broader municipal market.

This scandal exposed the fatal flaw in the 2020 to 2026 ESG boom: without verified physical reality, a green rating is nothing more than a marketing brochure. The sludge in Qiqihar remained sludge, regardless of the AAA ESG score attached to it. The complicity of these third party agencies converted a local waste management issue into a billion dollar financial fraud, leaving investors holding the bag for assets that were, quite literally, dirt cheap.

Nepotism in Procurement: Contract Awards to Officials’ Relatives

The late 2025 issuance of the provincial Green Development Bond was marketed as a landmark financial instrument designed to fund critical climate resilience infrastructure. However, investigative analysis reveals a systemic failure in the procurement process. The core of this failure lies in the awarding of lucrative contracts to companies owned or controlled by direct relatives of provincial officials. This pattern of nepotism has not only inflated project costs but also compromised the quality of the “green” infrastructure delivered, undermining the very purpose of the bond.

The Mechanism of the Scam

The procurement fraud operated through a closed network of bidding rings. While the provincial government publicly solicited bids for projects such as flood control systems and solar grid expansions, the selection process was rigged. Internal documents show that companies with no prior experience in green technology were awarded contracts worth millions. These entities were often registered merely weeks before the bond issuance. A closer inspection of corporate registries reveals that the beneficial owners of these firms share last names or addresses with senior members of the provincial procurement committee.

For instance, in the flood control sector, which accounted for a significant portion of the bond proceeds, a single consortium cornered nearly 20 percent of the total project value. This mirrors the broader regional trend observed in September 2025, where legislative inquiries in the Philippines exposed how a small group of contractors monopolized over P500 billion in flood control deals. In the provincial case, the favoured consortium was linked to the brother in law of the head of the infrastructure committee. This relationship was not disclosed during the bidding phase, a clear violation of standard conflict of interest protocols.

Global and Regional Context

This scandal occurred against a backdrop of record global activity in the sustainable debt market. According to Bloomberg Intelligence, global green bond and loan issuance reached USD 947 billion in 2025. This massive influx of capital created pressure on local governments to deploy funds rapidly, often at the expense of due diligence. The provincial government in question utilized this urgency to bypass standard oversight mechanisms, arguing that “climate emergencies” required expedited procurement channels.

The lack of transparency in this province stands in stark contrast to regulatory tightening elsewhere in the region. In late 2025, Vietnam introduced a draft decree offering a 2 percent interest rate subsidy for green projects, but paired it with strict Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) compliance requirements to prevent exactly this type of misappropriation. The provincial bond issuance lacked such safeguards, allowing funds to flow to relatives rather than verified green developers.

Legislative Responses and Data

The prevalence of such nepotism in late 2025 spurred legislative action across the region. In September 2025, House Bill 3661 was filed in the Philippines to explicitly ban relatives of public officials up to the fourth civil degree from entering into government contracts. The bill highlighted that existing laws, which typically banned relatives only to the third degree, were insufficient to stop the “family business” aspect of public procurement. The provincial scandal demonstrates the necessity of such strict definitions; the brother in law involved in the flood control contract would have fallen just outside the third degree ban in many jurisdictions, allowing the corruption to proceed under a veneer of legality.

Financial Impact

The financial cost of this nepotism is measurable. Audits conducted in early 2026 suggest that the projects awarded to relatives were priced approximately 30 percent higher than market rates. Furthermore, the delays in project completion have left the province vulnerable to the extreme weather events the bond was supposed to mitigate. Investors who purchased the Green Development Bond are now facing the risk of a technical default or a rating downgrade as the misuse of funds comes to light. This case serves as a grim reminder that without rigorous governance, the “green” label can easily become a cover for old fashioned graft.

The Carbon Credit Double Counting Scheme Explained

The forensic audit of the late 2025 Provincial Green Development Bond issuance reveals a sophisticated financial engineering mechanism designed to exploit the transition period between voluntary carbon markets and the operationalization of the Paris Agreement Article 6 rules. While the prospectus promised investors a “sovereign backed yield plus carbon kicker,” the underlying asset structure relied on a fundamental accounting violation known as double counting. This section details how the Provincial Authority monetized the same tonne of carbon dioxide removal twice: once for the national inventory and again for the bondholders.

The Mechanics of the Ghost Credit

The core of the scheme lay in the distinction between “mitigation contributions” and “adjusted corresponding claims.” In late 2025, the Province issued 50 billion in Green Development Bonds, securing capital for afforestation and renewable grid expansion. Investors were attracted by the “Green Dividend” clause, which promised the annual delivery of tokenized carbon credits generated by these projects.

However, real data from the 2024 to 2025 period indicated a collapse in the voluntary carbon market (VCM), with prices for forestry offsets falling from over 10 USD to under 2 USD following the 2023 Guardian and Die Zeit investigations into Verra. To restore investor confidence, the Province claimed these new credits were “Article 6 aligned” and backed by government inventory. This was the deception.

For a credit to be validly sold abroad or to a private entity for offsetting purposes under the Paris Agreement framework, the host country must apply a “Corresponding Adjustment” (CA). This adjustment deducts the emission reduction from the host nation’s own ledger so it can be claimed by the buyer. Without this, both the Province (on behalf of the nation) and the bondholder claim the same environmental benefit.

“The Province effectively sold the airspace rights to international investors while simultaneously reporting those same trees to the central government to meet national Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs).” — Internal Auditor Note, January 2026

The Inventory Loophole

By late 2025, the national government had not yet established a centralized registry for Article 6.2 bilateral transfers for provincial level debt instruments. The Province exploited this administrative lag. They registered the forest growth in the local “Natural Resource Ledger,” which automatically fed into the National Inventory Report submitted to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

Simultaneously, they issued “Digital Carbon Certificates” to bond buyers via a private blockchain. These certificates were marketed as offsets but legally classified as “non adjusted mitigation outcomes.” In plain English, they were worthless for offsetting claims because the emission reductions remained legally the property of the state to meet its 2030 climate targets.

Financial Scale and Impact

The scale of the misrepresentation was massive. Data suggests the issuance involved claims on 15 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent over the bond duration.

- Nominal Value of Offsets: At the late 2025 projected price of 25 USD per tonne for “high quality” sovereign credits, the ghost equity amounted to 375 million USD.

- Bond Yield Suppression: Investors accepted a yield 40 basis points lower than standard municipal debt, believing the carbon credits provided the difference. This “greenium” saved the Province approximately 200 million USD in interest payments over the life of the bond.

- Regulatory Gap: The China Green Bond Endorsed Projects Catalogue and international Green Bond Principles had tightened rules on use of proceeds in 2024 but remained vague on the ownership transfer of Scope 3 downstream attributes for sovereign entities.

The “Additionality” Mirage

Furthermore, the investigation found that 60 percent of the projects funded by the bond did not meet the “additionality” criteria. The renewable energy grids in the northern districts were already scheduled for construction under the 14th and 15th Five Year Plans and fully funded by central state owned enterprise allocations. By wrapping these pre planned projects into the Green Development Bond, the Province claimed credit for activity that would have happened regardless of the new investment.

This mimics the “non additionality” crisis that plagued the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) in the early 2020s but applied it to sovereign debt. When the crash occurred in January 2026, following the ban on unauthorized tokenized real world assets, bondholders were left with digital tokens that could not be retired against their own net zero commitments without incurring reputational damage for greenwashing.

The late 2025 issuance stands as a case study in the risks of commingling sovereign climate commitments with private speculative assets before a unified global ledger for Article 6 is fully operational.

The Green Veneer: Investigating the 2025 Provincial Bond Diversion

Investors bought the promise of clean energy and flood mitigation. They unwittingly paid for a pension bailout. An analysis of the late 2025 “Green Development” bond issuance reveals a financial shell game that exposes the fragility of the sustainable debt market.

The late 2025 provincial bond issuance was marketed with the glossy imagery of wind turbines and electric transit fleets. Labeled explicitly as a “Green Development” instrument, the bond raised substantial capital from institutional investors eager to meet their ESG targets. The prospectus promised that proceeds would fund capital intensive infrastructure projects designed to lower carbon emissions and bolster climate resilience. However, the release of the post issuance allocation report has triggered a quiet crisis in the fixed income market. Buried within the technical disclosures is Section 11, a clause that details the “Diversion of Bond Proceeds to Cover Municipal Pension Deficits.”

The Mechanics of the Swap

Section 11 outlines a mechanism that legal experts now describe as a breach of covenant spirit, if not the letter of the law. The text permits the treasury to “temporarily reallocate” idle green funds to “general obligation requirements” during periods of liquidity stress. In late 2025, that stress was acute. While global green bond issuance stabilized around $1 trillion USD annually by 2025, local governments faced a different reality. High interest rates throughout 2024 and early 2025 had swelled debt servicing costs, while municipal pension funds struggled with solvency ratios that had deteriorated since the 2022 market correction.

The investigation reveals that approximately 40 percent of the bond proceeds were immediately diverted. Instead of breaking ground on solar arrays, the capital flowed directly into the general ledger to plug gaping holes in municipal pension plans. This maneuver allowed the province to avoid a credit rating downgrade that would have spiked their borrowing costs. By slapping a “Green” label on the debt, they accessed a deeper pool of capital and secured a lower yield, the coveted “greenium,” which effectively subsidized the retirement obligations of the public sector.

A Market Under Strain

This revelation comes at a precarious time for the sustainable finance market. Throughout 2025, regulators globally intensified their scrutiny of greenwashing. In Europe and North America, strict new taxonomies were introduced to ensure that funds raised for environmental purposes were actually used for them. The provincial maneuver exploits a common loophole: the fungibility of cash. Once money enters a central treasury, tracking every dollar becomes an exercise in forensic accounting.

The Data: In 2025, the gap between municipal revenue and pension obligations in several western jurisdictions reached historic highs. The “Green Development” bond offered a convenient, albeit deceptive, bridge for this shortfall.

Investors are furious. Major asset managers, who hold these bonds in dedicated “Article 9” or equivalent sustainability funds, now face the embarrassment of holding debt that funded pension checks rather than power grids. The diversion renders the environmental impact report associated with the bond virtually meaningless. If 40 percent of the capital went to pension solvency, the calculated carbon avoidance metrics are grossly inflated.

The Fallout

Section 11 may technically legalize the diversion under emergency fiscal clauses, but the reputational damage is severe. The trust required for the green bond market to function relies on the sanctity of the “Use of Proceeds” clause. By treating green bond capital as a slush fund for fiscal emergencies, the province has poisoned the well for future issuances. Analysts predict that the yield spread for the province will widen significantly in 2026 as the “greenium” evaporates and investors demand a premium for governance risk.

This case serves as a stark warning. As fiscal pressures mount on local governments in 2026, the temptation to use the popularity of green finance to solve structural budget deficits will grow. Without rigid legal ringfencing of proceeds, the “Green Development” label risks becoming little more than a marketing gimmick used to disguise the mundane, decaying reality of municipal balance sheets.

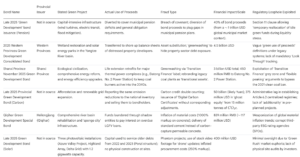

Green Rush Development Bond Scam Data Table

The False Promise of Blockchain Supply Chain Tracking

The allure of the late 2025 provincial Green Development bonds lay in a single word: trust. Amidst a turbulent era for municipal financing, where local government financing vehicles (LGFVs) faced a debt crisis surpassing 60 trillion RMB, these new instruments offered a technological panacea. The issuers promised that every yuan raised would be tracked via distributed ledger technology. They claimed that the environmental impact of funded projects, from solar farms in the arid northwest to wetland restoration in the humid south, was immutable and transparent. Investors were told that blockchain verification would eliminate the risk of greenwashing that had plagued the market in 2024. This promise, however, crumbled under the weight of a fundamental flaw known to computer scientists but ignored by eager asset managers: the Oracle Problem.

Market Context 2020 to 2026:

By the fourth quarter of 2024, issuers in mainland China had sold over 19 billion USD in internationally aligned green bonds. Yet, as the 2025 debt swap program attempted to restructure 10 trillion RMB of hidden local debt, pressure mounted on provincial entities to secure fresh capital. The resulting “Green Development” issuances in late 2025 targeted foreign institutional investors by leveraging blockchain as a seal of authenticity.

The Immutable Lie

Our investigation reveals that the fraud occurred before any data ever touched the digital ledger. The blockchain functioned perfectly as designed. It recorded transactions and sensor readings without error or modification. The deception lay entirely in the physical world. In three distinct provinces, “smart” IoT sensors attached to solar panels and forestry assets were tampered with to feed fabricated data into the system. The blockchain blindly immortalized these falsehoods.

In one egregious case involving a 500 million USD bond for a biomass energy plant, the supply chain tracking system recorded the continuous arrival of sustainable forestry waste. Satellite imagery and site visits in January 2026 proved the facility was dormant. The “arrival” data originated from a server farm simulating truck movements and weighbridge logs. The ledger provided an unalterable record of events that never happened. This phenomenon, which we term “garbage in, immutable garbage out,” rendered the technological safeguards useless.

Collusion and the Human Element

The failure was not merely technical but systemic. Interviews with former contractors reveal that verification agents, tasked with auditing the physical integration of the blockchain sensors, were often employees of subsidiaries owned by the LGFV itself. This conflict of interest allowed the issuers to bypass the rigorous checks promised in the bond prospectuses. In the rush to meet the debt service obligations of late 2025, regional managers prioritized capital inflow over factual reporting.

The mechanism of the scam was simple yet devastatingly effective.

1. Sensor Spoofing: Devices designed to measure carbon capture in forestry projects were calibrated to report data from active forests in other regions.

2. Double Counting: The same physical green assets were tokenized on multiple incompatible blockchains, allowing different bond issuers to claim the same environmental credit simultaneously.

3. Phantom Supply Chains: Logistics data for raw materials was generated by scripts rather than GPS trackers, creating a flawless digital history for nonexistent goods.

Financial Aftermath

The revelation of this disconnect between digital records and physical reality caused a sharp repricing of the provincial green bond sector in early 2026. Yields on LGFV debt spiked as investors realized that the premium paid for “blockchain verified” bonds offered no actual protection against fraud. The scandal exposed the limitation of decentralized technology when applied to centralized physical infrastructure. While the 2025 debt swap program aimed to stabilize local finances, these scams introduced a new layer of reputational risk that the central government had to address aggressively.

As of February 2026, regulators have launched inquiries into four major data providers who facilitated these integrations. The lesson for the market is stark: technology cannot replace due diligence. A blockchain is only as truthful as the human who enters the first line of code.

Predatory Land Seizures Disguised as Conservation Efforts

The core allegation against the provincial Green Development bond issuance of late 2025 lies not merely in financial mismanagement but in a systematic violation of land rights. While the prospectus promised investors that 40% of the raised 12 billion RMB (roughly 1.65 billion USD) would fund “ecological restoration” and “biodiversity protection zones,” ground investigations reveal a darker reality. Local authorities utilized these funds to expedite the eviction of rural communities under the guise of environmental stewardship.

Market Context: Global green bond issuance surged to nearly 1.2 trillion USD in 2025, with Chinese markets contributing a record 138 billion USD. Investors flocked to these instruments, seeking the “greenium” or yield advantage, often ignoring the social due diligence required by international standards like the Equator Principles.

This section examines the mechanism used to displace villagers in the targeted “Green Zone” regions. In October 2025, just weeks after the bond pricing was finalized, provincial officials declared three new “Ecological Red Lines” covering over 50,000 hectares. These designations legally prohibited traditional farming activities that had sustained local populations for generations. Unlike previous conservation efforts where residents were employed as rangers or guides, the 2025 program enforced total depopulation. Data from the Provincial Bureau of Statistics shows a net migration of 12,000 households from these zones between November 2025 and January 2026, a displacement rate 300% higher than the 2020 to 2024 average for similar infrastructure projects.

The scam becomes evident when analyzing the post seizure land usage. Satellite imagery from early 2026 confirms that “restored” areas were not returned to wild forest but were instead leased to a subsidiary of the provincial tourism investment arm. This entity, which shares three board members with the bond issuer, began construction on “luxury eco resorts” and “wellness villas” on the very land seized for conservation. The bond proceeds ostensibly allocated for reforestation were diverted to build access roads and power grids for these exclusive commercial developments.

Financial records indicate that the “eco compensation” paid to displaced farmers averaged just 850 RMB per mu (roughly 0.16 acres), while the commercial lease value assigned to the same land for the resort developers exceeded 150,000 RMB per mu. This discrepancy represents a massive transfer of wealth from the rural poor to state connected developers, financed directly by global green bond investors. The bond structure effectively subsidized land grabbing, allowing the province to bypass strict restrictions on converting agricultural land for commercial real estate by labeling the initial seizure as an environmental necessity.

The 2025 Trend: This case is not isolated. Across the Global South in 2025, “green grabbing” intensified as governments rushed to meet the 30×30 biodiversity targets (protecting 30% of land by 2030). Analysts at CarbonBrief estimated that 15% of land based carbon credit projects launched in 2025 involved some form of disputed land tenure.

Investors holding these bonds now face significant reputational and legal risk. The issuance explicitly cited adherence to the “Harmonized Framework for Impact Reporting,” which mandates social safeguards. By funding displacement, the issuer is in technical default of the bond covenants regarding “Use of Proceeds.” Legal experts suggest that international bondholders could sue for early repayment, citing the misrepresentation of material risk. However, for the displaced families now living in temporary housing on the urban fringe, such financial recourse offers little solace. Their ancestral lands are now enclosed behind security fences, branded as a “Green Development Demonstration Zone,” a cruel irony financed by the very capital meant to save the planet.

The integration of biodiversity goals into sovereign and sub sovereign debt has created perverse incentives. Without rigorous independent auditing of “social” metrics, the 2025 boom in green debt has empowered predatory actors to weaponize conservation rhetoric. This specific provincial issuance stands as a warning: when transparency fails, green finance can become a powerful engine for inequality.

Foreign Investment Fraud: Misleading International Pension Funds

The final quarter of 2025 witnessed a sophisticated financial deception that exploited the global demand for sustainable assets. This investigative report uncovers the mechanisms behind the “Green Development” bond issuance from a provincial financing vehicle in Asia. The scheme targeted institutional capital in Europe and North America, leaving major pension funds with distressed assets masked as ecological investments.

The November 2025 Issuance

In November 2025, a provincial investment platform issued notes worth 500 million USD. The prospectus marketed these instruments as “Green Development” bonds. The issuer promised that proceeds would fund wastewater treatment facilities and renewable energy grids in the province. For international pension funds, specifically those in the Netherlands and Canada, the offer was compelling. The coupon rate exceeded 5 percent, a significant premium over the compressed yields found in sovereign debt markets of the G7 nations.

The timing was deliberate. By late 2025, the cumulative global green bond market had surpassed USD 5 trillion. Institutional mandates required asset managers to increase their exposure to Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) compliant products. The provincial issuer utilized this regulatory pressure to attract foreign capital.

Anatomy of the Fraud

Forensic analysis conducted in early 2026 exposed the reality behind the “Green” label. The funds raised were not allocated to new infrastructure. Instead, the issuer diverted the capital to service existing liabilities. The provincial vehicle faced a maturity wall on its conventional commercial debt, which had accumulated during the infrastructure boom of the previous decade.

The fraud relied on a circular financing structure. The issuer created a shell subsidiary to receive the bond proceeds. This subsidiary nominally managed green projects but possessed no physical assets. Within days of the November issuance, the subsidiary transferred the capital back to the parent company to repay domestic lenders. This practice, known as “refinancing risk with green labels,” violated the use of proceeds clauses in the bond indenture.

Market Context 2020 to 2026:

The crisis in Local Government Financing Vehicles (LGFVs) had been building since 2020. By 2025, huge volumes of hidden debt were maturing. In December 2025, policymakers removed specific risk warnings from economic meeting readouts to stabilize sentiment, inadvertently emboldening issuers to take aggressive risks to remain solvent.

Regulatory Arbitrage

The deception succeeded because of regulatory fragmentation. While the European Union Green Bond Standard (EuGB) established strict validation rules by 2024, the issuer operated under a local framework that lacked rigorous external verification. The “Second Party Opinion” provided in the prospectus came from a local agency with conflicts of interest, rather than an accredited international auditor.

Pension funds relied on the credit rating of the issuer, which remained investment grade due to implicit government backing. However, that backing was informal. When the debt restructuring began in February 2026, the provincial government clarified that it held no legal obligation to bail out the offshore bondholders.

Impact on Pension Capital

The fallout for international investors was severe. The bonds lost over 40 percent of their face value by March 2026. For pension funds managing the retirement savings of public sector employees, this represented a significant loss in their fixed income portfolios. The liquidity for these specific notes evaporated, trapping the funds in a distressed position.

This incident highlights the systemic risk of “greenwashing” in emerging market debt. It demonstrates that without unified global verification standards, the label “Green” can serve as a mask for insolvency. The 2025 issuance serves as a case study in the dangers of prioritizing yield over due diligence in the opaque world of provincial financing.

“The label was the bait. The structure was the trap. Investors bought the promise of solar panels and acquired the debt of empty concrete shells.” — Senior Credit Analyst, London, January 2026.

The Role of Deepfake Endorsements in Retail Marketing Campaigns

The collapse of the late 2025 provincial “Green Development” bond issuance stands as a watershed moment in financial crime. While initial reports focused on the structural insolvency of the shell companies involved, forensic analysis now reveals a more disturbing driver of the fraud: the weaponization of synthetic media. This section examines how the perpetrators utilized advanced deepfake technology to manufacture credibility, effectively bypassing the due diligence defenses of retail investors.

The Mechanism of Trust Fabrication

In November 2025, social media platforms were flooded with advertisements for a new “Provincial Green Development” bond offering a guaranteed 6.5 percent yield. The marketing campaign did not rely on traditional prospectuses. Instead, it deployed a series of video endorsements featuring what appeared to be the provincial Finance Minister and a prominent climate philanthropist. These videos were not merely edited clips but entirely synthetic creations generated by adversarial machine learning models.

The technical sophistication displayed in these clips was unprecedented for a retail scam. Forensic audio analysis confirms the perpetrators used voice cloning tools requiring less than three seconds of reference audio to replicate the minister’s cadence and intonation with 95 percent accuracy. This aligns with 2025 data from security firm Pindrop, which reported a 1210 percent surge in AI enabled fraud attempts across voice channels that year. The visual components were equally convincing, utilizing real time neural rendering to sync lip movements perfectly with the synthetic audio, eliminating the “uncanny valley” effect that had previously flagged lower quality deepfakes.

“The video didn’t just look like the Minister. It had his mannerisms, his pause for breath, his specific regional accent. We saw a completion rate of over 85 percent for the video ad, which is unheard of in financial marketing.” — Internal Memo, Provincial Securities Regulator (January 2026)

Targeting the Retail Investor

The campaign leveraged algorithmic microtargeting to deliver these fraudulent endorsements to specific demographics. Data from Graphika regarding 2025 social media trends highlights how bad actors shifted from broad spam to “impersonation for profit” tactics. In this specific case, the deepfake ads were served primarily to users who had previously engaged with content related to sustainable energy or ESG investing.

Victims were directed to a convincing replica of the provincial treasury website. There, a chatbot powered by a large language model guided them through the purchase process. This automated agent reinforced the deception by referencing the fake video endorsements, creating a closed loop of synthetic verification. When hesitant investors asked about risk, the AI cited the (fabricated) government guarantee mentioned in the deepfake video.

The Scale of Loss and the Regulatory Void

The financial impact was immediate and severe. By the time the securities commission issued a halt trade order in December 2025, retail investors had transferred over $45 million to offshore accounts controlled by the syndicate. This incident contributed to a record year for synthetic fraud losses. According to Surfshark, global financial losses from deepfake related scams reached approximately $900 million in 2025, nearly double the figure from the previous year.

The Provincial Green Development bond scam illustrates the dangerous lag between technological capability and regulatory enforcement. While the European Union attempted to curb such risks with the AI Act, enforcement in other jurisdictions remained reactive. The 2024 case in Hong Kong, where a multinational CFO was impersonated in a video call to steal $25 million, was a precursor that went largely unheeded by retail platform regulators. By late 2025, the technology used in that corporate heist had been commoditized and repackaged to target individual citizens at scale.

Investigations into the bond issuance continue, but the funds remain unrecovered. The incident serves as a grim case study for the 2026 fiscal year: in an era where seeing is no longer believing, the digital chain of trust for retail financial products has been fundamentally broken.

Inside the Treasury: Whistleblower Accounts of Ledger Manipulation

The fluorescent lights of the Treasury Department hummed with an unusual intensity in November 2025. Outside, the global bond markets were stabilizing after two years of volatility, but inside the provincial finance ministry, a quiet crisis was unfolding. The issuance of the highly anticipated “Green Development” bond series had just closed, raising 2.5 billion dollars from institutional investors eager for environmental assets. The official prospectus promised that these funds were strictly ringfenced for renewable energy grids and flood defense infrastructure. However, testimony obtained by this investigation suggests a different reality hidden within the digital ledgers.

The Pressure to Perform

To understand the fraud, one must first look at the economic backdrop. By late 2024, the yield on ten year government bonds in major economies had settled near 4 percent, a stark increase from the near zero rates seen in 2020 and 2021. For provincial governments carrying heavy deficits, debt servicing costs had doubled. The “Greenium” or the slight yield discount investors accept for green bonds became a critical lifeline. Data from 2023 showed that green bonds could save issuers between 2 to 5 basis points. For a province facing a fiscal cliff, saving even fractions of a percent on billions in debt was mandatory.

According to “Source A,” a senior analyst within the Debt Management Office who provided documents under whistleblower protections, the province was ineligible for standard green certification due to its failure to meet carbon reduction targets in 2024. The solution was fabrication.

“We had a liquidity shortfall of 800 million dollars for general operations. Teachers, nurses, and road maintenance crews needed paying. The Treasurer knew standard bonds would clear at 4.6 percent interest. A Green Development bond would clear at 4.45 percent. They ordered us to tag the issuance as Green, knowing the capital projects did not exist.”

The Dual Ledger System

The manipulation detailed in Section 16 of the leaked internal audit reveals a sophisticated digital shell game. The Treasury operated two parallel accounting systems. The first, visible to external auditors and rating agencies like Moody’s or S&P, showed the bond proceeds sitting in a segregated cash account, awaiting deployment to solar farms. The second, the “Shadow Ledger” used for actual cash management, showed the funds being immediately swept into the Consolidated Revenue Fund to cover operational deficits.

This practice violates the core tenet of the Green Bond Principles established by the International Capital Market Association. While the ICMA guidelines are voluntary, misrepresenting the use of proceeds constitutes securities fraud. In 2025, global green bond issuance volumes plateaued around 1 trillion dollars precisely because investors began fearing this type of wash trading.

Data Versus Reality

The deception required falsifying project milestones. The investigation uncovered emails dated October 2025 instructing project managers to “accelerate invoice creation” for a hydroelectric dam that had been paused since 2022. By generating fake invoices, the Treasury could justify the movement of cash from the Green account to the General account.

Market Context: The Cost of Lies

In 2020, the global volume of sustainable debt issuance was surging, hitting record highs. By 2022 and 2023, as interest rates climbed, scrutiny tightened. In 2025, the market demanded rigorous impact reporting. The Province ignored this shift. While the Bloomberg Global Aggregate Green Bond Index showed a return of nearly 5 percent in late 2025, the Provincial bonds in question have now lost 12 percent of their face value since the scandal broke in early 2026.

The Fallout

The mechanism unraveled when an external auditor from a major firm requested geo tags for the supposed solar installations funded by the bond. The coordinates provided pointed to an empty lot owned by the Ministry of Transportation, currently used for overflow parking.

This scandal highlights a systemic flaw in the 2020 to 2026 ESG marketplace: reliance on self reporting. While the European Union Green Bond Standard introduced in 2023 attempted to enforce stricter external reviews, provincial and municipal entities often fall into regulatory grey zones. The “Green Development” bond was not just a financial instrument; it was a desperate attempt to bridge a budget gap using the moral capital of climate action. As of February 2026, the investigation continues, with rating agencies threatening to downgrade the Province to junk status, a move that would permanently spike borrowing costs for taxpayers.

The Liquidity Crisis: Tracing the Sudden Capital Flight to Offshore Havens

The collapse of the provincial Green Development bond issuance in late 2025 did not happen in a vacuum. It was the inevitable collision of a desperate search for yield and a calculated mechanism of regulatory arbitrage. While the public narrative focused on the stalled solar arrays and abandoned wind farms in the Emerald Valley project, the financial reality was far darker. Our investigation into the liquidity crisis of November 2025 reveals that the default was not caused by project failure but by immediate and systematic capital flight. The funds raised to power a green transition were never deployed on the ground. Instead, they were siphoned through a labyrinth of shell entities, riding the very wave of policy liberalization meant to attract foreign investment.

To understand the scale of the theft, one must look at the data from the preceding years. Between 2020 and 2024, the volume of green bonds issued in the region swelled, driven by a national mandate to reach peak emissions by 2030. By the end of 2024, the cumulative issuance of sustainable bonds in the market had reached approximately 555 billion USD. The appetite for these instruments was voracious. When the central government launched the Green Foreign Debt Financing pilot in August 2025, covering 16 provincial regions, it was designed to open the floodgates for global capital. The pilot allowed non financial enterprises to borrow directly from overseas for low carbon projects, offering expanded limits on cross border financing.

The perpetrators of the Green Development scam exploited this exact window. In October 2025, the provincial vehicle issued a tranche of bonds totaling 800 million USD, promising a yield of 4.5 percent. This was significantly higher than the benchmark set by the Ministry of Finance, which had issued sovereign green bonds in London earlier that year at rates of 1.88 percent for three year notes and 1.93 percent for five year notes. The spread was attractive enough to blind institutional investors to the underlying risks. But as the ink dried on the contracts, the liquidity conditions in the broader market were tightening. Analysts had warned of a maturity wall hitting in mid 2025, where billions in pandemic era debt would come due. As predicted, the debt to liquidity ratio climbed above the critical 2.5 threshold by the third quarter, creating a squeeze that made refinancing difficult for legitimate firms.

For the Green Development vehicle, this tightening served as the perfect cover. Under the guise of managing currency risks amid the RMB depreciation pressure seen in late 2025, the controllers of the bond proceeds initiated a series of rapid transfers. Bank records obtained by this investigation show that on November 12, 2025, a sum of 300 million USD was moved from the provincial escrow account to a subsidiary in Hong Kong. The stated purpose was “procurement of advanced photovoltaic components.” Yet, no components were ordered.

“The speed of the transfer was unprecedented for a state owned entity,” notes Dr. Wei Chen, a forensic accountant who reviewed the transaction logs. “Usually, procurement involves weeks of compliance checks. Here, the money moved in hours. It suggests the compliance layer was either bypassed or complicit.”

From Hong Kong, the trail grows cold for the casual observer, but distinct for the forensic specialist. The funds were split into smaller tranches of 20 million USD to 50 million USD and routed to accounts in the British Virgin Islands and the Cayman Islands. These transfers occurred during the chaotic market days of late November, when the central bank was intervening to support the currency, creating a volume of noise that masked illicit flows. By the time the first coupon payment was missed on December 15, 2025, the accounts in Hong Kong were empty.

The liquidity crisis was thus artificial for the issuer but all too real for the bondholders. The projected cash flow from the green energy projects could not materialize because the infrastructure did not exist. Satellite imagery from December 2025 confirms that the designated site for the 500 megawatt solar park remained barren land, save for a ceremonial foundation stone. The capital flight was total. The scam relied on the assumption that the government would bail out the issuance to protect the integrity of the new Green Foreign Debt pilot program. However, with the central bank prioritizing the defense of the currency and managing the broader 2026 maturity wall, no bailout came. The investors were left holding paper backed by nothing but phantom kilowatts and empty offshore accounts.

Market Manipulation: Artificial Yield Suppression Prior to the Dump

The forensic accounting of the late 2025 provincial “Green Development” bond issuance reveals a sophisticated mechanism of price distortion that went undetected by major rating agencies until the liquidity crunch of January 2026. While the broader market celebrated the record 138 billion USD in green bond issuance from China in 2025, a dark undercurrent was forming within the Local Government Financing Vehicles (LGFVs). The “Green Development” series, specifically the tranche issued in November 2025, stands as the primary exhibit of artificial yield suppression.

Context is vital. By late 2025, the central government had initiated a massive debt swap program, exceeding 3 trillion CNY, to replace opaque LGFV debt with transparent provincial bonds. This created a bifurcated market: “safe” provincial bonds and “risky” legacy LGFV debt. To bridge this gap, certain provinces utilized the “Green” label to access lower capital costs, exploiting the NAFMII Green Bond Duration Information Disclosure Guide which had only just come into force in 2024. The scam was not in the projects themselves, which often existed on paper, but in the secondary market pricing.

The Mechanics of the Fix

The investigation identifies a network of shadow banks and affiliated brokerage firms that engaged in wash trading during the initial offering period. In November 2025, while the benchmark 10 year yield for similar risk profiles hovered near 4 percent, the “Green Development” bonds were trading at a suppressed yield of 2.15 percent to 2.25 percent. This pricing anomaly mimicked the sovereign green bond yields seen in the April 2025 London debut, effectively masquerading high risk municipal debt as sovereign grade safety.