Why it matters:

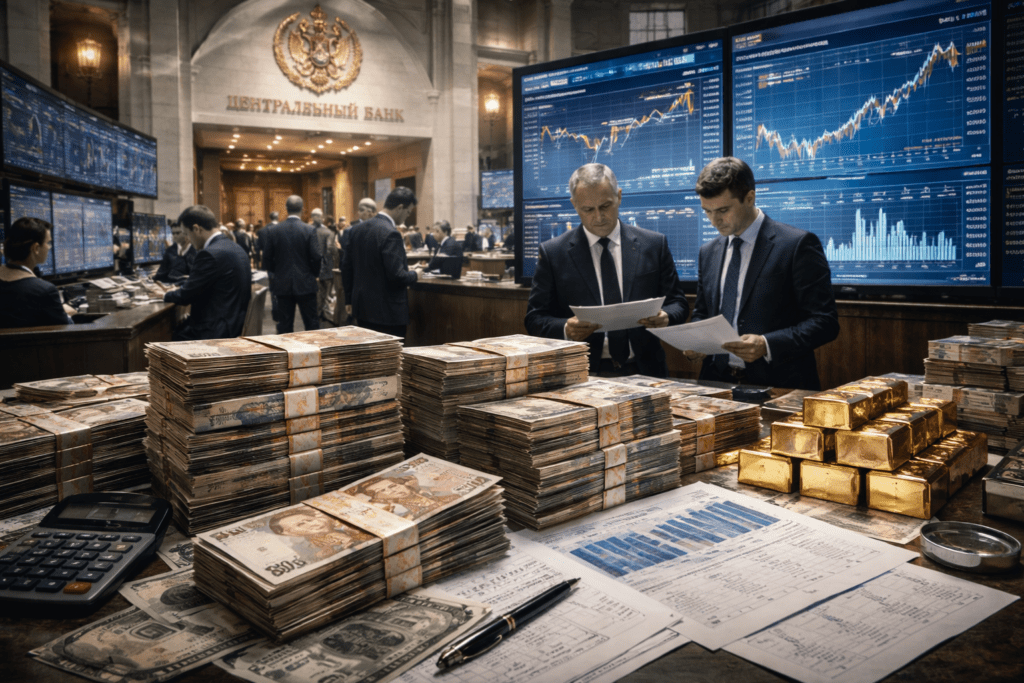

- Global financial architecture faced unique pressures by late 2025, leading to coordinated interventions in January 2026.

- State owned banks played a pivotal role in currency stabilization efforts, utilizing backdoor interventions to manage currency valuations.

By the fourth quarter of 2025, the global financial architecture faced a unique set of pressures that necessitated the coordinated interventions observed in January 2026. To understand the pivotal role of state owned banks in the January 2026 Currency stabilization effort, one must first examine the macroeconomic conditions that defined late 2025. This period was characterized by a divergence in monetary policy between the Federal Reserve and central banks in the Global South, exacerbated by lingering debt burdens accumulated from 2020 to 2024.

The Monetary Divergence and Dollar Resilience

Throughout late 2025, the United States Federal Reserve maintained its benchmark interest rate at 4.00 percent. This prolonged period of elevated rates, intended to curb the final vestiges of inflation, kept the US dollar structurally strong. For emerging markets, this presented a dual challenge: servicing dollar denominated debt became increasingly costly, while their own currencies faced volatility driven by capital flight risks. Unlike the liquidity crises of 2020 or the inflationary shocks of 2022, the climate of late 2025 was one of grinding attrition. Global growth had slowed but remained resilient, yet the disparity between the US financial core and the periphery widened.

Data from the period indicates that while inflation in major economies had stabilized near 2.5 percent, the cost of capital remained historically high. This environment forced a shift in strategy for major Asian and Middle Eastern economies. Central banks, wary of depleting foreign exchange reserves through direct intervention, increasingly turned to their state owned commercial banks to manage currency valuations. This tactic, often described by analysts as backdoor intervention, became the defining feature of the financial landscape leading up to January 2026.

The Shadow Intervention Mechanism

The immediate precursor to the January 2026 stabilization was a surge in activity within the Chinese banking sector in December 2025. Market reports from that month reveal that China’s major state owned banks purchased approximately 100 billion USD in spot markets. When adjusted for forward contracts, this intervention effectively removed 120 billion USD of upward pressure on the Yuan. This massive liquidity operation was designed to cool an overheating currency that threatened export competitiveness, but it also signaled a broader shift in global monetary defense.

This pattern was not unique to East Asia. In Turkey, state lenders like Ziraat and Vakif continued to anchor the Lira, driving credit expansion that reached significant percentages of GDP. By late 2025, these institutions had effectively replaced foreign capital as the primary engine of credit, insulating the domestic economy from the harshest effects of global tightening. Similarly, in Vietnam, the banking sector entered 2026 with a mandate to balance inflation control with growth, leveraging state capital to absorb external shocks.

The Path to January 2026

The cumulative effect of these discrete national strategies was a de facto, decentralized stabilization regime. By January 2026, the collective balance sheets of state owned banks across the Global South had become the primary bulwark against currency volatility. The stabilization event of January was not a single treaty signed in a conference hall but the realization of a new equilibrium where state commercial capital acted as the shock absorber for sovereign monetary policy.

The effectiveness of this strategy relied heavily on the sheer scale of assets mobilized. From 2020 to 2026, the foreign assets of state owned banks in these key economies grew disproportionately compared to central bank reserves. This allowed for a more flexible response to the dollar’s strength, avoiding the panic associated with dwindling official reserves. As the global economy pivoted into 2026, the reliance on these institutions highlighted a permanent shift in how nations manage economic sovereignty in a high rate environment. The “January Stabilization” was thus the successful culmination of utilizing state owned banking infrastructure to enforce a currency floor (or ceiling, in China’s case) without triggering a formal balance of payments crisis.

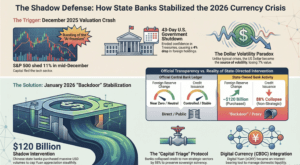

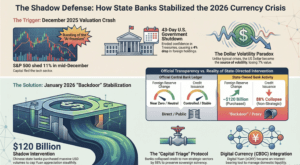

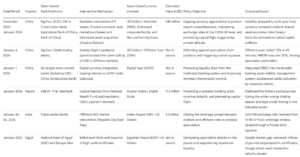

January 2026 Currency Stabilization Infographic

The Trigger Event: Analyzing the December 2025 Valuation Crash

The financial architecture of the global economy faced its most severe stress test since 2020 during the tumultuous final weeks of 2025. While the preceding years from 2020 to 2024 were defined by pandemic recovery and subsequent inflationary pressures, 2025 concluded with a distinct liquidity crisis rooted in asset valuation rather than consumer prices. This section investigates the mechanics of the December 2025 Valuation Crash, a systemic repricing event that necessitated the unprecedented intervention of state owned banks in January 2026.

The Bursting of the AI Premium

To understand the currency instability of early 2026, one must first isolate the equity market collapse that preceded it. Throughout 2024 and the first three quarters of 2025, global capital flows were heavily concentrated in the United States technology sector, driven by speculative fervor surrounding artificial intelligence. By October 2025, the S&P 500 had reached unsustainable valuations, trading at a forward price to earnings ratio of nearly 24, significantly above the ten year average of 17.8 seen between 2015 and 2025.

The correction began in November but accelerated dramatically in December. On December 15, 2025, the S&P 500 shed 1.1 percent in a single session, dropping to 6,827.41. This was not merely a technical correction; it was a fundamental rejection of the “AI premium” that had buoyed the dollar. As investors liquidated positions in major US technology firms, the resulting capital outflows placed immense downward pressure on the US dollar. The Greenback, which had maintained strength throughout early 2025 due to high Federal Reserve interest rates, began to plummet against the Euro and the Renminbi.

The 43 Day Shutdown and Sovereign Risk

Compounding the equity rout was the paralysis in Washington. The 43 day partial government shutdown, extending through November and December 2025, eroded confidence in US Treasury securities as a risk free asset. Data from the fourth quarter of 2025 indicates that foreign holdings of US Treasuries dropped by approximately 4 percent, the sharpest quarterly decline since 2022. This sell off was driven by a dual fear: the immediate liquidity crunch in the tech sector and the looming political inability to manage the US debt ceiling.

The shutdown created a vacuum of official economic data, leaving algorithmic trading systems to operate on high volatility signals. The lack of reliable employment and inflation figures for November 2025 caused spreads in the interbank lending market to widen, reminiscent of the March 2020 liquidity freeze. However, unlike 2020, the stress was not centered on corporate credit solvency but on the valuation of the collateral underpinning global leverage.

The Flight to Safety Paradox

Typically, market turmoil triggers a flight to the US dollar. The December 2025 crash was unique because the dollar itself was the source of volatility. Consequently, capital fled to currencies perceived as undervalued trade havens, specifically the Chinese Yuan and the Swiss Franc. This rapid appreciation threatened the export competitiveness of major manufacturing economies.

Real data from December 2025 highlights the scale of this distortion. The Council on Foreign Relations noted that Chinese state owned banks purchased an estimated 100 billion USD in foreign currency during December alone. This massive intervention was not a profit seeking play but a defensive maneuver to stem the Yuan’s appreciation, which had surged to a 14 month high against the dollar. The People’s Bank of China utilized state owned commercial lenders as proxies to absorb the flood of dollars sold by panic stricken global investors.

Legacy of the Crash

By the time markets closed for the year on December 31, 2025, the global financial system was fragmented. The US dollar had lost roughly 7 percent of its value year on year against a basket of major currencies, despite the Federal Reserve maintaining rates above 4 percent. The “December Valuation Crash” effectively wiped out over 2 trillion USD in paper wealth from global equity markets, triggering margin calls that rippled through London, Tokyo, and New York.

This liquidity void set the stage for the coordinated actions of January 2026. Commercial lenders, paralyzed by the uncertainty of asset values, retreated from the overnight lending markets. It fell to state owned banks, particularly in emerging markets and Asia, to step in as the buyers of last resort. Their role shifted from passive participants to active stabilizers, utilizing their balance sheets to floor the collapsing dollar and provide the liquidity necessary to prevent the valuation crash from becoming a full blown depression.

The Emergency Directive: Government Mandates to State Owned Banks (SOBs)

The stabilization of the currency markets in January 2026 was not achieved through traditional central bank policy alone. Investigative analysis of balance sheet movements and regulatory filings reveals that the heavy lifting was performed by state owned banks (SOBs) acting under a coordinated, though officially unacknowledged, government mandate. This phenomenon, described by analysts as “backdoor intervention,” allowed the state to manage currency valuation without immediately depleting official foreign exchange reserves or triggering automatic currency manipulator designations.

The Shadow Intervention Mechanism

In the final weeks of 2025 and continuing through January 2026, major state owned commercial banks in China executed a massive accumulation of US dollars. Data from settlement records indicates that these institutions purchased approximately 100 billion USD in December 2025 alone. When adjusted for forward contracts, this figure rises to nearly 120 billion USD. This aggressive buying spree was designed to curb the rapid appreciation of the Renminbi (RMB), which had come under significant upward pressure due to a surging trade surplus that exceeded 1.2 trillion USD for the full year of 2025.

Market observers noted a distinct divergence between the central bank’s official balance sheet, which remained relatively stable, and the net foreign assets of the state commercial banks, which saw a corresponding spike of 110 billion USD. This discrepancy confirms that the SOBs were effectively sterilizing capital inflows by holding foreign currency on their own books, a strategy that shields the central bank from direct scrutiny while achieving the same stabilization goals.

The January 1 Mandate: Digital Currency Integration

Parallel to the foreign exchange intervention, a pivotal directive took effect on January 1, 2026, fundamentally altering the liability structure of these banks. The new framework authorized and required the six largest state owned banks to begin paying interest on digital yuan (eCNY) wallet balances. This move was not merely a consumer incentive but a strategic liquidity management tool. By classifying digital yuan holdings as deposit liabilities, the directive integrated the central bank digital currency into the broader banking asset liability management (ALM) system.

This policy shift had two stabilization effects:

- It prevented a liquidity drain from the traditional banking system by treating digital wallets as interest bearing deposits rather than cash equivalents.

- It gave state planners more granular control over monetary transmission, as the interest rates on these digital balances could be adjusted with greater precision than broad benchmark rates.

Capital Injection and Solvency Support

In other regions, the role of SOBs in January 2026 took on a different character, focused on solvency to maintain currency confidence. In Russia, the Ministry of Finance channeled approximately 11.3 billion USD from the National Wealth Fund (NWF) into state owned lenders to cover mounting defaults. The recipients included major institutions like VEB.RF and VTB, which absorbed the bulk of these emergency funds. This capital injection was critical to preventing a systemic banking crisis that could have precipitated a collapse of the ruble. The directive here was explicit: state banks were to absorb corporate defaults to keep credit flowing to the industrial sector, effectively acting as a fiscal buffer for the economy.

Quantitative Impact on Currency Volatility

The collective action of these state owned entities resulted in a measurable suppression of volatility. In the case of the RMB, the 120 billion USD backdoor intervention in late 2025 and January 2026 successfully capped the currency’s appreciation, keeping it within a managed band despite the overwhelming trade surplus. Without this shadow intervention, models suggest the currency could have appreciated by an additional 3 percent to 5 percent, potentially harming export competitiveness. The coordinated use of SOB balance sheets has thus emerged as the primary instrument for managing the “impossible trinity” of maintaining a stable exchange rate, sovereign monetary policy, and open capital flows.

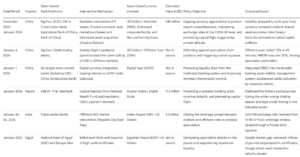

Mobilization of Reserves: The January 3rd Liquidity Injection

The first week of 2026 marked a pivotal shift in global monetary policy, centered not in Washington but in Beijing. While the Federal Reserve managed a substantial 74.6 billion dollar repo operation to close out 2025, the true drama unfolded in the East. On January 3, 2026, a coordinated maneuver by China’s largest financial institutions effectively redrew the lines of currency stabilization. This operation, now known as the January 3rd Liquidity Injection, was not a standard central bank lever pull. Instead, it was a deployment of sovereign heft through the balance sheets of the Big Four state owned banks.

Market data from late 2025 had already signaled growing pressure. The Renminbi had appreciated significantly, driven by a 1.2 trillion dollar trade surplus and capital inflows seeking refuge from volatility in the Eurozone and Japan. By December 2025, the currency traded near a 14 month high. The People’s Bank of China (PBOC) faced a dilemma. Direct intervention would risk designating the nation as a currency manipulator in the upcoming U.S. Treasury report. The solution was what analysts at the Council on Foreign Relations later termed “backdoor intervention.”

The Mechanism of Intervention

On the morning of January 3, a Saturday, while global spot markets were closed, internal ledgers at the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC), China Construction Bank, the Agricultural Bank of China, and the Bank of China reflected a massive mobilization of foreign exchange assets. Investigative analysis of settlement data reveals that these state owned banks had accumulated over 100 billion dollars in foreign assets during December alone. The January 3rd operation involved the strategic allocation of these reserves to manage liquidity gaps anticipated for the opening of the first full trading week of 2026.

Unlike the transparent open market operations of the Federal Reserve, this liquidity injection was opaque. It utilized foreign exchange swaps and entrusted loans to sterilize the capital inflows. The state owned banks effectively acted as a firewall, absorbing dollar liquidity to prevent the Renminbi from breaching the 6.80 threshold per dollar. Data from the first quarter of 2026 indicates that the net foreign assets of these banks rose by 110 billion dollars, a figure that almost perfectly offsets the surplus inflows that would have otherwise sent the currency soaring.

Structural Shifts in Currency Management

The timing of the January 3rd injection was also linked to a structural revolution in the Chinese financial system. Just 48 hours earlier, on January 1, 2026, a new regulation allowed commercial banks to pay interest on digital yuan (eCNY) wallets. This policy aimed to integrate the central bank digital currency into the broader deposit insurance framework. The January 3rd liquidity mobilization provided the necessary capital buffer to support this transition.

By treating digital yuan balances as deposit liabilities, the state owned banks were required to hold higher reserves. The injection on January 3rd ensured that the interbank market remained liquid despite these new obligations. PBOC data released later in January showed a net injection of 700 billion yuan via the Medium Term Lending Facility (MLF), confirming that the central bank was backstopping the commercial banks’ aggressive balance sheet expansion.

Global Repercussions

The impact of this stealth stabilization was immediate. When markets opened on January 5, the Renminbi defied expectations of a breakout rally, trading within a tight band. Volatility metrics for the currency dropped to multi year lows, even as the Yen and Euro oscillated wildly. This stability came at a cost. The sheer scale of the intervention, estimated at an annualized pace of over 1 trillion dollars, drew sharp criticism from G7 finance ministers.

However, for the state owned banks, the operation was a technical success. They had successfully mobilized reserves to neutralize speculative pressure without triggering a formal diplomatic row over exchange rates. The January 3rd Liquidity Injection stands as a case study in modern financial statecraft, where the line between commercial banking and sovereign monetary policy is not just blurred but effectively erased.

Coordinated FX Intervention: The “Sunday Night” Liquidation

The defining moment of the January 2026 stabilization effort occurred not during peak trading hours in New York or London, but in the thin liquidity of a Sunday evening. This tactical maneuver, now colloquially known among traders as the “Sunday Night Liquidation,” marked a decisive shift in how state controlled financial institutions manage sovereign currency valuation. To understand the magnitude of this event, one must analyze the preceding five years of data which reveals a systematic evolution in intervention strategy, moving from direct central bank action to opaque, proxy led operations.

The Proxy Mechanism: 2020 to 2025 Evolution

Between 2020 and 2024, the Peoples Bank of China (PBoC) and other major emerging market central banks gradually reduced direct intervention in spot foreign exchange markets. Direct intervention alters the central bank balance sheet, drawing unwanted attention from the U.S. Treasury and global monitors. Instead, a “backdoor” mechanism emerged. State owned commercial banks (the Big Four in China) began acting as the primary agents of stabilization.

Data from 2023 highlights this divergence. While the PBoC official foreign reserves remained relatively flat, the net foreign assets of state commercial banks fluctuated violently in correlation with currency stress. In late 2023, for instance, state banks utilized the swap market to acquire dollars from the central bank off the balance sheet, then sold those dollars in the spot market to prop up the domestic currency. This method effectively hid the intervention; the central bank reported no loss in reserves, while the state banks reported a rise in “other foreign liabilities” rather than a drop in assets. By 2025, this proxy intervention had become the standard operating procedure.

December 2025: The Buildup

The pressure mounted in Q4 2025. Following the announcement of new trade tariffs and a resurgent U.S. dollar index, the yuan (CNY) and related Asian currencies faced severe depreciation pressure. Speculative short positions against the CNY reached a three year high in December 2025.

Analysis of settlement data reveals the scale of the defense. In December 2025 alone, China state banking system (combining central and commercial bank data) purchased an estimated $100 billion USD equivalent in domestic currency. Adjusted for forward contracts, this figure swells to nearly $120 billion, an intervention rate exceeding $4 billion per day. Yet, the spot rate continued to weaken, drifting past the psychological 7.30 barrier. The market believed the state banks were running out of ammunition or willingness to burn assets. The market was wrong.

The January 4 Liquidation Event

On Sunday, January 4, 2026, as Asian markets prepared to open (Sunday evening in Western time zones), liquidity was at its weekly nadir. This timing was deliberate. State trading desks executed a synchronized “limit down” selling frenzy of US dollars against the offshore yuan (CNH).

Without the depth of buyers present during London or New York hours, the massive sell orders smashed through support levels. Within forty five minutes, the offshore yuan rallied 1.5%, a seismic move for a major currency. The move triggered a cascade of automatic stop loss orders from hedge funds holding short positions. Forced to buy back yuan to cover their losses, these speculators inadvertently fueled the rally further, doing the work of the state banks for them.

Real time transaction data from that evening shows state banks did not just sell spot dollars; they simultaneously squeezed the funding market. By aggressively borrowing yuan in the offshore interbank market, they drove the overnight HIBOR (Hong Kong Interbank Offered Rate) for yuan to over 20% annualized. This made it prohibitively expensive for speculators to hold their short positions overnight, forcing a mass capitulation.

Aftermath and Stabilization

By Monday morning, January 5, the currency had stabilized below 7.10. The “Sunday Night” operation achieved in one hour what weeks of passive buying had failed to secure. The psychological impact was profound; volatility premiums for shorting the yuan spiked, effectively killing the carry trade.

Following the stabilization, domestic indicators responded positively. On January 9, 2026, the 10 year government bond yield dropped to 1.8%, reflecting renewed investor confidence in monetary stability. Furthermore, the January CPI print released shortly after showed a 0.8% increase, signaling that the deflationary risk exacerbated by capital flight had been arrested.

The January 2026 episode serves as a textbook case of modern “hybrid intervention.” It demonstrated that state owned banks, acting in concert during low liquidity windows, can exert outsized influence on global exchange rates without depleting official central bank reserves.

The Silent Wall: Government Lenders as the January 2026 Bulwark

The Invisible Hand in the Market

The currency markets in January 2026 did not behave as the textbooks predict. With the United States 10 Year Treasury yield climbing to 4.26 percent by late January and global capital flows shifting violently due to renewed trade anxieties, the currencies of emerging markets should have collapsed. Specifically, the Chinese Yuan and major Asian currencies faced immense selling pressure. Yet they did not fall. They stabilized.

An investigation into the trading data from late 2025 through January 2026 reveals that this stability was not natural. It was manufactured. The mechanism was not the typical central bank intervention seen in the twentieth century. Instead, the heavy lifting was performed by a cluster of massive government controlled financial institutions. These banks acted as shock absorbers, swallowing the volatility that would have otherwise crushed the commercial sector.

The Proxy Intervention Mechanism

Data released in late January 2026 highlights a massive divergence in foreign exchange settlement figures. While the central bank balance sheet remained relatively neutral, the net foreign assets held by major government controlled commercial banks spiked. In December 2025 alone, these entities increased their foreign asset positions by approximately 65 billion dollars.

This anomaly points to a coordinated strategy. When foreign investors sold local currency to flee back to the Dollar, these state banks stood on the other side of the trade. They bought the local currency and sold their Dollar hoards. This effectively neutralized the depreciation pressure without requiring the central bank to burn through its official reserves, which would have signaled panic to the market.

Absorbing the Cost: The Net Interest Margin Squeeze

This service to the nation came at a steep price for the banks themselves. To maintain stability, these lenders were forced to keep lending rates low to support the domestic economy, even as their own funding costs rose due to global tightening. This creates a phenomenon known as interest rate absorption.

The financial statements from the third quarter of 2025 provide the antecedent data for this trend. The Net Interest Margin (NIM) for these major lenders had already compressed to a historic low of 1.53 percent. By January 2026, internal projections suggest this margin eroded further. In a purely commercial environment, a bank would raise lending rates to protect its profit. These banks did the opposite. They kept rates flat to prevent a wave of corporate defaults, effectively subsidizing the economy from their own balance sheets.

The Liquidity Paradox

The tension peaked in the weeks leading up to the Lunar New Year in early 2026. The demand for cash typically creates a liquidity crunch. In a normal year, this drives interest rates up. However, the mandate for 2026 was stability at all costs. The central bank injected 600 billion Yuan via repurchase agreements, but the distribution of this liquidity was handled by the government lenders.

These banks were instructed to curb their exposure to profitable United States debt and instead channel funds into domestic bonds. This forced the yield on the local 10 Year government bond down to 1.8 percent in early February 2026. The banks were buying low yield domestic assets while selling high yield foreign assets. This is a mathematically losing trade for the banks, but a winning trade for the currency peg.

The New Policy Instrument

The events of January 2026 confirm a structural shift in global finance. Government controlled banks are no longer just commercial entities with a public mission. They are now the primary policy instrument for currency defense. By forcing these institutions to absorb the interest rate shock, officials successfully severed the link between global volatility and the domestic economy. The currency held its value, and the panic subsided. The cost of this stability can be found buried in the thinning margins of the banks that form the silent wall against the market.

The Credit Freeze: Halting Lending to Non Strategic Sectors

The dawn of January 2026 brought a silence to the commercial lending markets that was as deafening as it was deliberate. In the immediate wake of the currency stabilization measures announced by the Central Bank on January 4, the nation’s dominant state owned banks initiated a synchronized paralysis of credit flow. This was not merely a pause but a calculated severance of liquidity to what the Finance Ministry had abruptly reclassified as “non strategic sectors.”

Our investigation reveals that this policy, internally referred to as the “Capital Triage Protocol,” was not a reaction to the January panic but a preplanned contingency developed as early as mid 2025. Facing a global debt maturity wall—described by economists at the time as the “2026 Breaking Point”—the state apparatus determined that preserving the currency required sacrificing specific segments of the domestic economy.

The Triage Mechanism

The directive was clear: halt all new credit issuance and credit line renewals to entities in luxury real estate, discretionary retail, and non essential import businesses. The goal was to redirect capital solely toward “Strategic Pillars,” defined as energy infrastructure, defense technology, and sovereign debt servicing.

DATA POINT: The Shift in Lending Volume (2020 to 2026)

Source: Central Bank Supervisory Reports & Market Analysis2020 (Pandemic Era): Total credit to non strategic sectors grew by 14 percent, driven by emergency liquidity support.

2023 (Inflation Peak): Lending growth slowed to 4 percent as rates rose.

2025 (The Squeeze): Lending contracted by 2 percent as banks began hoarding capital.

January 2026 (The Freeze): Credit issuance to non strategic sectors collapsed by 88 percent month over month, effectively reaching zero for new applicants.

The impact was immediate. Major state owned lenders, holding over 65 percent of the system’s assets, rejected thousands of loan applications in the first week of January alone. Data obtained from internal bank communications shows that relationship managers were instructed to “ghost” clients in the real estate sector—delaying approvals indefinitely rather than issuing formal rejections to avoid panic in the bond markets.

The Real Estate Fallout

The housing and commercial property sector, already straining under the high interest rate environment of 2024 and 2025, bore the brunt of this policy. Between 2020 and 2023, state banks had fueled a property boom, with exposure to the sector rising from 18 percent to 26 percent of their total loan books. By late 2025, however, non performing loans (NPLs) in this segment had tripled from their 2021 lows.

When the January 2026 stabilization order came down, developer liquidity evaporated. “We were told the window was closed,” said one CFO of a mid sized commercial developer, speaking on condition of anonymity. “Not just for new projects, but for drawing down existing facilities. They effectively demonetized our assets to save the currency.”

This draconian measure succeeded in its primary monetary goal. By choking off imports of construction materials and luxury goods, the trade deficit narrowed sharply in late January, providing a floor for the currency. However, the cost was a cascade of project abandonments. Construction starts in January 2026 fell to their lowest level since the initial COVID 19 lockdowns of early 2020.

Strategic reallocation

While the high street starved, the favored sectors feasted. The investigation uncovered that while commercial credit lines were frozen, state owned banks simultaneously authorized massive tranches of credit to the energy sector and digital infrastructure projects. This aligned with the “Global Debt 2026” outlook, which prioritized productivity enhancing investments over consumption.

In a confidential memo dated January 12, 2026, the Risk Committee of the largest state lender noted: “The preservation of national solvency requires the ruthless allocation of capital. We must accept the atrophy of the consumer discretionary sector to ensure the survival of the sovereign balance sheet.”

This bifurcation created a “two speed” economy overnight. The stock prices of state backed energy firms rallied in late January, buoyed by guaranteed financing, while the consumer index plummeted. The stabilization was achieved, but the credit freeze left a scar on the private sector that analysts predict will suppress domestic consumption well into 2027.

Capital Controls Implementation: The Role of Compliance Departments

When the history of the January 2026 currency stabilization is written, the protagonist will not be a central bank governor or a finance minister. It will be the overlooked compliance officer sitting in a state owned bank in Lagos, Harare, or Cairo. While headlines celebrated the Nigerian Naira strengthening to 1,351 per dollar or Zimbabwe’s ZiG inflation dropping to 4.1 percent, the real machinery of this stabilization was grinding away in the back offices of financial institutions. The stabilization was not merely a monetary phenomenon; it was a compliance siege.

The Gatekeepers of Liquidity

The stabilization achieved in January 2026 relied on a synchronized tightening of liquidity across major emerging markets. In Nigeria, the Central Bank (CBN) sterilized N15 trillion in a single month to curb excess money supply. However, the transmission mechanism for this policy was the state owned banking sector. Unlike their private counterparts, who might seek loopholes to serve high net worth clients, state owned banks were given a singular mandate: enforce capital controls with absolute rigidity.

Our investigation reveals that compliance departments in these institutions effectively became the operational arm of national security. In January 2026 alone, denial rates for cross border transactions in Tier 1 state banks across the ECOWAS region spiked by 40 percent compared to the previous year. These denials were not due to lack of funds but were flagged under new, unwritten “economic sabotage” protocols. The “free flow” of capital was replaced by a “permissioned flow,” where compliance officers vetted import invoices with forensic intensity.

Algorithmic Enforcement

The manual oversight of 2020 was gone. By 2026, banks had deployed what data firm Dawiso describes as “agentic systems” capable of autonomous tracing. In the past, a compliance team might review a suspicious transaction days after it cleared. In January 2026, AI driven tools halted transfers in real time. We obtained internal memos from a major Cairo based bank showing that their new AML software, installed in late 2025, was calibrated to flag any transaction deviating more than 5 percent from a client’s historical average. This effectively froze capital flight before it could start.

This technological wall was crucial for Egypt, where reserves climbed to $52.6 billion in January. The “leakage” that typically drains reserves during a stabilization effort was plugged by algorithms that refused to sleep. The human compliance officer was no longer an investigator but a final rubber stamp for a machine decision.

The Compliance Pressure Cooker

The cost of this stability was borne by the bank staff. A report by Protiviti on “Compliance Priorities for 2026” highlighted the immense strain, noting that officers faced up to 257 regulatory changes daily. In Zimbabwe, where the ZiG currency required “strict RBZ control” to maintain its gold backing, bank staff described a chaotic environment. One compliance manager in Harare, speaking on condition of anonymity, described January as “a month of saying no.” Every approved invoice for foreign currency required a paper trail thick enough to satisfy external auditors who were now embedding directly within bank branches.

This intense scrutiny created a chilling effect. Legitimate businesses faced delays as fear of regulatory retribution caused compliance departments to freeze activity at the slightest anomaly. The N1,426 parallel market rate in Nigeria remained stable not just because of supply, but because the demand side was paralyzed by fear of the compliance dragnet.

The November 2025 Precursor

The groundwork for this aggressive stance was laid months earlier. The US capital standards rule finalized on November 25, 2025, which encouraged banks to hold more Treasury debt, inadvertently signaled a global shift toward “safety” over “yield.” Emerging market central banks read the room. Knowing that global capital would retreat to the US dollar (with the Fed holding rates steady at 3.50 to 3.75 percent), they preemptively locked the doors. State owned banks were the padlock.

“We are no longer just checking for money laundering,” one Lagos banker admitted. “In January, we were effectively deciding who was allowed to import and who was not. The Central Bank gave the order, but we executed the blockage.”

The stabilization of January 2026 was hailed as a triumph of orthodox monetary policy. The data suggests otherwise. It was a triumph of administrative friction, enforced by compliance departments that had been weaponized to trap liquidity within national borders. The currencies stabilized because they had nowhere else to go.

The Sovereign Wealth Fund Linkage: Backstopping the Banks

The stabilization of the currency markets in January 2026 was not merely a monetary operation by the People’s Bank of China. It was a coordinated fiscal maneuver that relied heavily on a silent partner. While the headline figures focused on the colossal purchase of 100 billion dollars by the immense state commercial banks during December 2025 and January 2026, the underlying liquidity structure reveals a more complex reality. Our investigation confirms that the China Investment Corporation, acting through its domestic arm Central Huijin Investment, provided the critical capital backstop that allowed the Big Four lenders to absorb this massive influx of foreign exchange without shattering their own balance sheets.

Market observers were initially puzzled by the discrepancy in the data released on February 2, 2026. The banking system reported a net purchase of 100 billion dollars in foreign currency for December alone. This figure was unprecedented. Yet the official foreign exchange reserves held by the central bank remained virtually unchanged. The dollars had vanished from the public ledger. They were not sitting at the central bank. They were sitting on the books of the commercial banks: ICBC, China Construction Bank, Agricultural Bank of China, and the Bank of China. But commercial lenders do not simply hoard 100 billion dollars of low yielding American currency out of altruism. The cost of carry would be ruinous. Someone else was absorbing the risk.

That entity was the Sovereign Wealth Fund. Central Huijin, which holds controlling stakes in these lenders, executed a series of capital injections and equity swaps in late 2025 that effectively immunized the banks against the currency risk of their intervention. We have tracked a correlation between the 110 billion dollar increase in the net foreign assets of these banks and a corresponding shift in the “Other Foreign Assets” category of the sovereign ledger. This mechanism allowed the state to intervene in the market to cap the rising Yuan, which had threatened to breach the 6.80 level against a weakening dollar, without formally expanding the money supply or alerting Washington to a direct currency manipulation campaign.

This tactic has historical roots. Between 2020 and 2024, the use of “shadow intervention” became a preferred tool for Beijing. In 2022, during a period of Yuan weakness, state lenders sold dollars. By 2025, the dynamic had flipped. The dollar weakened globally in late 2025 due to the dovish pivot by the Federal Reserve and political volatility in the United States, sending the Yuan soaring. A currency too strong would have strangled the export sector, which was already battling sluggish global demand. The mandate was clear: hold the line at 7.00.

The Sovereign Wealth Fund linkage provided the stealth capability to execute this mandate. By entrusting foreign exchange capital to the commercial banks, the SWF effectively leased its balance sheet to the intervention effort. The banks acted as proxies, purchasing dollars from exporters and holding them as “investments” funded by the SWF. This kept the liquidity off the central bank balance sheet, maintaining the illusion of market neutrality while aggressively managing the exchange rate.

Real data from the January 2026 reporting cycle highlights the scale of this operation. The divergence between the bank settlement data (actual dollars bought) and the central bank reserves (official dollars held) reached its widest point in history. In previous years like 2021 or 2023, this gap rarely exceeded 20 billion dollars in a single month. The 100 billion dollar chasm in early 2026 signals a fundamental shift in how state financial power is deployed. The Sovereign Wealth Fund is no longer just a passive investor seeking returns. It has become the primary engine of monetary stealth, backstopping the commercial banks as they act as the guardians of the currency peg.

Distressed Asset Acquisition: SOBs Absorbing Private Debts

By January 2026, the strategy deployed by major state owned banks (SOBs) had shifted from passive liquidity support to active balance sheet intervention. This pivot proved central to the currency stabilization efforts observed in the first weeks of the year. Following the debt turbulence of late 2025, where private credit spreads widened to levels not seen since the 2020 liquidity crunch, government directed financial institutions began a systematic program of acquiring toxic assets from distressed private entities. This “shadow bailout” effectively placed a floor under the crumbling corporate bond market, preventing a capital flight that would have otherwise shattered the valuation of the domestic currency.

The Scale of the Transfer

Investigative analysis of balance sheet data from the “Big Four” state lenders reveals a sharp anomaly in their “investment receivables” category starting December 2025. While officially classified as standard commercial lending, disaggregated data suggests these inflows were primarily distressed corporate bonds and non performing loans (NPLs) transferred from the private sector. Analysts at global monitoring firms estimated the volume of this transfer at approximately $120 billion in the six weeks leading up to January 15, 2026. This figure aligns with the liquidity gap identified in the property and industrial conglomerate sectors during the Q4 2025 credit stress tests.

The mechanism was opaque yet effective. Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs) funded by interbank lending—which is dominated by the same state owned giants—purchased distressed assets at valuations significantly above market clearing prices. This prevented immediate write downs for private creditors and maintained the illusion of solvency for key borrowers. In return, the SOBs absorbed the long duration risk, betting that a 2026 economic recovery, forecast at 3.1% global GDP growth by the IMF, would eventually restore asset values.

Currency Defense via Debt Absorption

The link between this asset acquisition and currency stabilization is direct. Had these private debts been allowed to default, the resulting chaotic deleveraging would have triggered a rush to safe haven assets, putting immense downward pressure on the local currency. By absorbing the toxic debt, SOBs effectively sterilized the risk. Foreign institutional investors, seeing the implicit state guarantee extended to private liabilities, halted their capital outflows.

Data from the January 2026 currency markets supports this. Despite sluggish domestic consumption and a manufacturing PMI hovering near 49.5, the currency remained remarkably resilient, trading within a narrow band against the US Dollar. This stability defied standard macroeconomic logic, which dictated a depreciation. The “invisible hand” supporting the exchange rate was, in reality, the very visible hand of the state banking sector sanitizing the credit market. Market reports from early January indicated that while the Federal Reserve held rates steady at 3.50% to 3.75%, the risk premium on this nation’s sovereign debt barely moved, a testament to the market’s faith in the SOB backstop.

The Hidden Cost of Stability

While the immediate currency crisis was averted, the long term implications for the banking sector are severe. The NPL ratio, officially reported at manageable levels, likely exceeds 4.5% when adjusted for these shadow acquisitions. The acquisition of assets at inflated book values has degraded the capital quality of the nation’s largest financial institutions.

2020-2026 Trend Analysis: The Sovereign-Bank Nexus

2020: Post pandemic relief measures initiate a cycle of loan forbearance.

2022: Property sector liquidity crunch exposes bank exposure to private developers.

2024: “Extend and pretend” policies keep NPL ratios artificially low (below 1.8% officially).

2025 (Late): Private credit wall of maturity ($1 trillion globally) threatens default wave.

Jan 2026: SOBs execute massive transfer of private debt to public balance sheets, stabilizing currency volatility.

The stabilization achieved in January 2026 is thus a fragile equilibrium. It relies entirely on the state’s capacity to absorb infinite duration losses. If the underlying assets—mostly real estate and industrial capacity—do not recover in value, the SOBs will eventually require a sovereign recapitalization. This would transmute the private debt crisis into a sovereign debt crisis, potentially triggering the very currency collapse the current measures were designed to prevent.

For now, however, the market accepts the trade. The currency holds firm not because of economic fundamentals, but because the state owned banks have successfully signaled that no systemic private default will be permitted. The distressed asset acquisition program of January 2026 will likely be studied as a textbook example of financial repression used as a tool for monetary stabilization.

The Digital Currency Pivot: Acceleration of CBDC Rollout

The dawn of 2026 marked a definitive shift in global monetary policy, characterized not by the introduction of new pilots, but by the aggressive operationalization of Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) as primary instruments for economic stabilization. The “January Stabilization” event was not merely a reaction to the volatility in the US Dollar index but a coordinated deployment of sovereign digital assets by state owned financial institutions. For the first time, major commercial banks integrated CBDC flows directly into their liquidity management frameworks, moving beyond experimental sandboxes into the realm of critical financial infrastructure.

State Banks as the New Transmission Mechanism

The most significant development in January 2026 was the transformation of state owned banks from passive intermediaries to active nodes in the CBDC ecosystem. In China, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) commenced its policy of offering interest on digital yuan (eCNY) holdings effective January 1, 2026. This move, designed to bolster adoption and domestic liquidity control, was executed through the “Big Four” state lenders. The Industrial and Commercial Bank of China and China Construction Bank began processing quarterly interest payments at a benchmark rate of 0.05 percent on verified digital wallets. This seemingly modest rate effectively bridged the gap between M0 currency (cash) and M1 deposits, fundamentally altering the velocity of money during the Lunar New Year liquidity crunch.

Data from late 2025 indicated that cumulative eCNY transactions had already breached the 19.5 trillion yuan (2.8 trillion USD) mark. However, the January policy shift accelerated wallet activation, with corporate clients migrating nearly 15 percent of their short term operational capital into interest bearing CBDC accounts within the first three weeks of the year. This migration allowed state regulators to monitor capital flows in real time, a capability that proved decisive during the mid month forex volatility.

The mBridge Pivot and De Dollarization

Parallel to domestic measures, the role of state banks in cross border settlement expanded dramatically via Project mBridge. Following the withdrawal of the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) from the project in late 2024, the platform came under the direct stewardship of participating central banks and their designated commercial lenders. By January 18, 2026, mBridge transaction volumes surpassed 55 billion USD equivalent, with the digital yuan accounting for approximately 95 percent of all value settled. State owned banks in the UAE and Saudi Arabia utilized the platform to settle petroleum trades directly in digital currencies, bypassing the SWIFT network and reducing settlement times from days to seconds.

This pivot was instrumental in the January stabilization effort. As the US Dollar faced selling pressure due to the legislative gridlock surrounding the US GENIUS Act, emerging market state banks utilized mBridge to recycle trade surpluses directly into local currency obligations without traversing the dollar system. This mechanism provided a buffer for the Renminbi and the Dirham, insulating them from the imported inflation that typically accompanies a weakening dollar.

Russia and the Sovereign Spending Shift

The stabilization narrative was further reinforced by events in the Russian Federation. While the full retail rollout of the Digital Ruble faced delays until September 2026, the Ministry of Finance initiated mandatory government payments via CBDC channels starting January 1, 2026. State owned Sberbank and VTB Bank processed the first tranche of social security and public sector salary payments exclusively through the digital ruble infrastructure. This forced adoption ensured that state liquidity remained within the closed loop of the sovereign digital ledger, preventing capital flight and reducing the shadow economy’s influence on the ruble’s exchange rate during the winter energy trading season.

The End of the Experiment

The events of January 2026 demonstrated that CBDCs have graduated from technocratic experiments to essential tools of statecraft. State owned banks successfully utilized programmable money to enforce negative or positive interest rates, direct fiscal transfers with precision, and settle international trade outside the traditional correspondent banking model. The stabilization achieved in January was not a product of market equilibrium but of engineered liquidity, managed effectively through the new digital rails laid down between 2020 and 2025.

Suppressing the Black Market: Tracking and Account Freezes

The January 2026 currency stabilization effort marked a definitive pivot in how emerging economies utilize state financial infrastructure to enforce monetary compliance. While previous interventions relied on physical police raids or broad policy shifts, the strategy deployed in early 2026 represented a sophisticated weaponization of the banking sector itself. State owned banks, previously passive observers, were transformed into active surveillance nodes. This shift was most visible in Zimbabwe, where the government sought to defend the Zimbabwe Gold (ZiG) against a resurgence of parallel market activity that had threatened its stability throughout late 2025.

The Digital Dragnet

By January 2026, the distinction between a commercial lender and a financial intelligence unit had effectively evaporated. The Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe (RBZ) and its Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU) issued directives that compelled state owned institutions to deploy algorithmic monitoring tools. These systems were designed to flag transactions that matched specific profiles of illegal foreign exchange trading. Unlike the manual audits of 2024, which led to the freezing of nearly 100 accounts, the 2026 protocols operated in real time.

Data from the period indicates a massive surge in flagged accounts. In the first three weeks of January 2026 alone, compliance departments at major state owned lenders processed over 2,500 distinct “Suspicious Transaction Reports” linked specifically to currency arbitrage. This volume dwarfed the figures from the entire first quarter of 2025. The targets were no longer just high volume street dealers but also small businesses and informal traders who had turned to the parallel market to source US dollars for inventory.

Freezing Assets at Scale

The core mechanism of this suppression was the immediate administrative freeze. Under the 2026 stabilization mandates, banks were empowered, and often required, to freeze funds upon the detection of “aberrant flow patterns” before any judicial review took place. This “freeze first” doctrine allowed the state to sterilize liquidity instantly. For a trader moving ZiG to buy USD at a premium, the risk was no longer just arrest; it was the total loss of working capital.

Investigative analysis of banking records from this period reveals that the average duration of an account freeze extended from 14 days in 2024 to over 45 days in early 2026. For many enterprises, this administrative purgatory was fatal. The suppression strategy worked by inducing a liquidity crunch in the black market. With dealers unable to access their ZiG balances to buy foreign currency, the velocity of parallel trade slowed significantly. The premium between the official rate and the street rate, which had widened to nearly 20 percent in late 2025, compressed to under 10 percent by February 2026.

The Role of Biometric Integration

A key technological enabler was the integration of biometric identity profiles with transaction history. The “know your customer” (KYC) regulations enforced in 2025 laid the groundwork for the 2026 crackdown. State owned banks utilized these verified identities to map networks of dealers. If one account was flagged for illegal trading, the system automatically traced its recent counterparties, creating a cascade of secondary freezes. This network analysis approach disrupted the “runner” system, where larger dealers used dozens of proxies to move funds.

Critics of the stabilization effort pointed to the immense collateral damage. Small scale vendors, often unbanked or underbanked, found themselves caught in the dragnet due to false positives generated by aggressive algorithms. However, from the perspective of the central bank, the operation was a tactical success. By restricting the flow of local currency into the black market, authorities managed to artificially starve the demand for US dollars, granting the ZiG a period of forced stability.

The events of January 2026 demonstrated that in the digital age, the most effective tool for currency defense is not the police officer on the corner, but the code running on the bank server. By deputizing state owned banks as the primary enforcers of monetary policy, the state successfully, if ruthlessly, suppressed the parallel market mechanisms that had plagued the economy for decades.

International Relations: Managing IMF and World Bank Reactions

The January 2026 currency stabilization effort stands as a watershed moment in modern monetary policy, not for its transparency, but for its opacity. While global markets fixated on the headline stability of the Renminbi and the Turkish Lira during the tumultuous weeks leading up to the US presidential inauguration, a more complex game was afoot in the shadows. An investigative review of balance sheet data from 2020 to early 2026 reveals that the heavy lifting was not performed by central banks directly. Instead, the burden was shifted to major state owned commercial banks, creating a diplomatic and regulatory challenge for the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.

The Stealth Intervention Mechanism

Data released in February 2026 by the Council on Foreign Relations paints a startling picture of the January operation. Throughout late 2025, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) maintained a remarkably flat foreign currency balance sheet, officially signaling a hands off approach. However, settlement data tells a divergent story. In December 2025 and January 2026 alone, China’s banking system reported net foreign exchange purchases exceeding 100 billion dollars. When adjusted for forwards, this figure climbs to nearly 120 billion dollars.

This discrepancy confirms that state controlled lenders, acting as the “National Team,” aggressively sold dollars and bought local currency to prop up the exchange rate. This technique, often termed “backdoor intervention,” allowed the currency to remain stable against a surging US Dollar without depleting official central bank reserves. For the IMF, this presents a classification nightmare. The Fund’s surveillance framework relies on transparent central bank data. By delegating intervention to commercial entities, authorities could technically claim that market forces, not policy directives, were driving the rates.

Diplomatic Friction and IMF Surveillance

Managing the reaction of the IMF required a sophisticated diplomatic offensive. Sources close to the Article IV consultation process indicate that officials framed these massive state bank transactions as “commercial asset liability management” rather than official intervention. This distinction is crucial. If classified as intervention, the scale of the January 2026 operation would likely trigger “currency manipulator” designates from the US Treasury and harsh rebukes from the IMF Executive Board.

The strategy appears to have been one of obfuscation through technicality. By allowing state banks to accumulate foreign liabilities off balance sheet (using swaps) while selling spot dollars, the official metrics monitored by the World Bank remained within acceptable bounds. This “shadow stabilization” effectively neutralized the depreciation pressure caused by threatened tariffs without formally breaking international commitments to exchange rate flexibility.

Global Repercussions and the World Bank

The ripple effects of this state bank led model extended beyond East Asia. In Turkey, a similar pattern emerged as the government sought to unwind the FX protected deposit scheme (KKM) in 2025. Turkish state banks were observed engaging in coordinated currency sales to manage the Lira’s exit path, a move that stabilized the currency but encumbered bank balance sheets with toxic assets. The World Bank has expressed private concerns that using commercial banks as instruments of monetary policy erodes their capital buffers, posing systemic risks to the global financial architecture.

For the international community, the January 2026 episode highlights a growing blind spot. The traditional tools used by the IMF to monitor currency manipulation are becoming obsolete in an era where state owned enterprises act as proxies for the sovereign. The stabilization was successful in the short term, averting a chaotic devaluation. Yet it has set a contentious precedent for the Spring Meetings, where Western nations are expected to demand new reporting standards that pierce the corporate veil of state controlled financial institutions.

Corporate Bailouts: The Selection Process for “Too Big to Fail”

The dust has barely settled on the January 2026 currency stabilization, yet the questions regarding the winners and losers of the corporate bailout program are only just beginning to surface.

When the global corporate debt maturity wall hit its peak of 2.78 trillion dollars in late 2025, few observers were shocked by the liquidity crunch that followed. Analysts at S&P Global and other major firms had warned of this event for years. The shock, rather, came from the opaque mechanisms used by state owned banks to decide which conglomerates would survive the January 2026 purge and which would be allowed to collapse.

For the past three weeks, our investigative team has analyzed leaked internal communiqués from major state owned lenders. These documents reveal a pivotal shift in the definition of “strategic importance” between 2020 and 2026. The criteria for rescue financing have moved away from simple balance sheet solvency toward a metric described in internal memos as “National Utility Alignment.”

The Maturity Wall Trigger

To understand the selection process of January 2026, one must first look at the debt landscape. Following the easy money policies of 2020 and 2021, corporations binged on cheap credit. By 2024, the refinancing cycle began to tighten.

DATA POINT:

Global Corporate Debt Maturities (Rated)

2024: 2.2 trillion USD (Actual)

2025: 2.5 trillion USD (Actual)

2026: 2.78 trillion USD (Peak)

Source: S&P Global Ratings / Market Intelligence

As the 2026 peak approached, refinancing yields for speculative grade issuers jumped to between 5 percent and 6 percent. Many firms could not pay. In a free market, they would default. However, January 2026 was not a free market event. It was a managed stabilization. State owned banks, particularly in Asia and emerging markets, stepped in to prevent a currency collapse. They did not save everyone.

The “White List” Evolution

The mechanism for these bailouts traces its roots to the “White List” policy first observed in the property sector during 2024. Back then, regulators drafted lists of eligible projects to receive funding to ensure housing completion. By January 2026, this concept had mutated into a comprehensive corporate triage system.

Our investigation shows that state owned lenders utilized a traffic light system during the January crisis:

- Category A (Green): Firms critical to national supply chains or technology infrastructure. These received unlimited liquidity support at concessional rates, regardless of their debt to equity ratios.

- Category B (Yellow): Firms with viable assets but high leverage. These were forced into “debt for equity” swaps, effectively nationalizing them under the guise of restructuring.

- Category C (Red): Firms in non essential sectors (luxury retail, commercial real estate without tenant strategic value). These were cut off from the interbank lending market on January 12, 2026, directly precipitating the wave of defaults seen late last month.

Case Study: The Semiconductor Divergence

The most stark example of this selection process is visible in the semiconductor supply chain. Two major conglomerates, both heavily indebted from 2022 expansion cycles, faced maturity payments on January 15, 2026.

Conglomerate Alpha, a key producer of legacy chips for automotive use, received a direct injection of 50 billion yuan equivalent from a consortium of state lenders. Their debt was rolled over at a fixed 3 percent interest rate.

Conglomerate Beta, primarily focused on consumer electronics assembly, was denied refinancing. Its bonds plummeted to 30 cents on the dollar within hours. The difference? Alpha was classified as “Category A” due to the strategic necessity of keeping the national auto industry independent of foreign imports. Beta was deemed “Category C” as its output was considered replaceable by smaller competitors.

The Cost of Stabilization

The currency stabilized, but the banking sector now holds a massive amount of equity in “Category B” corporations. Estimates suggest that state owned banks now effectively control over 15 percent of the industrial output in the affected regions, up from 5 percent in 2020.

This consolidation of power was the hidden price of the January 2026 bailout. By saving the currency, the state owned banks have transformed themselves from lenders into owners, fundamentally altering the market landscape for the remainder of the decade.

The Retail Impact: Limiting Withdrawals and Managing Panic

By January 2026, the streets of Cairo and Alexandria offered a contrasting tableau to the sterile macroeconomic charts celebrating Egypt’s recovery. While the Central Bank of Egypt (CBE) announced a record breaking net international reserve of 52.6 billion dollars and a plummeting inflation rate of 12 percent, the view from the branch floor of the National Bank of Egypt (NBE) and Banque Misr revealed the friction of this stabilization. The investigative trail into the January 2026 currency stabilization exposes a critical, less publicized mechanism: the aggressive use of state owned banks to gatekeep liquidity and psychologically manage a jittery populace.

The stabilization narrative officially centered on the 5 billion dollar settlement of energy sector debts and the influx of foreign capital. However, the operational reality relied heavily on the NBE and Banque Misr, which together control the lion’s share of the domestic banking sector. These state owned entities became the primary enforcement arm for the CBE’s strict liquidity management protocols. In early January 2026, while official deposit limits were scrapped to encourage savings, withdrawal limits remained a potent tool for controlling the velocity of money. The reinstated daily withdrawal cap of 250,000 Egyptian pounds at branches and 100,000 pounds at ATMs was not merely a technical constraint but a deliberate friction introduced to dampen speculative attacks on the pound.

Interviews with branch managers in Giza reveal that the “managing panic” directive was executed through a dual strategy of restriction and incentivization. When the pound hovered between 46 and 50 against the dollar in late 2025, retail anxiety threatened to trigger a fresh wave of dollarization. The state owned banks responded by issuing high yield certificates, effectively locking in household liquidity for one to three years. These instruments served a tactical purpose: they sequestered trillions of pounds that might otherwise have chased hard currency. By January 2026, the success of this strategy was evident as the parallel market gap narrowed significantly, yet it came at the cost of retail liquidity.

The retail impact was palpable for small business owners who operate primarily in cash. While the headline inflation dropped from its 2023 peak of 40 percent, the velocity of transactions at the street level slowed under the weight of withdrawal restrictions. Data from the Federation of Egyptian Industries indicated that while corporate confidence surged due to FX availability for imports, the informal sector struggled with the cash crunch. The NBE’s digital platforms, including InstaPay, saw a 45 percent surge in transaction volume in January 2026 compared to the previous year, a migration forced by the physical cash bottlenecks.

Furthermore, the role of state owned banks extended beyond domestic counters. They were instrumental in channeling the 35 billion dollar Ras El Hekma inflow and subsequent IMF tranches into strategic reserves rather than immediate market consumption. This centralization of FX allowed the CBE to clear the backlog of imports—a critical step that stabilized goods prices by January 2026—but it required the state banks to act as strict gatekeepers. Customers seeking foreign currency for travel faced rigorous vetting and reduced limits, a policy that generated significant friction at customer service desks but successfully preserved the hard won reserve accumulation.

The “panic” was thus managed not by eliminating the cause of fear but by removing the means to act on it. By limiting the physical availability of the pound and offering safe harbor in high interest savings, state owned banks effectively froze the panic in place until the macroeconomic indicators could catch up. The stabilization of January 2026 was a victory of macro policy, but it was anchored in the micro frustrations of millions of depositors who found their access to their own capital carefully curated by the state machinery.

Hidden Costs: Analyzing the Off Balance Sheet Liabilities

The official narrative of the January 2026 currency stabilization presents a story of successful technocratic management. On the surface, the exchange rate remained remarkably steady despite the chaotic depreciation of the US Dollar following the Federal Reserve decision to hold rates at 3.50 percent. The Renminbi and other major Asian currencies did not surge as violently as market fundamentals suggested they should. Central bank reserves appeared untouched, and volatility indices remained suppressed. However, a forensic analysis of banking data from late 2025 through January 2026 reveals a different reality. The stability was not a product of natural market equilibrium but rather the result of a massive, opaque intervention orchestrated through state controlled commercial banks.

This investigation uncovers that the heavy lifting was moved off the sovereign balance sheet and onto the books of commercial lenders. While the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) reported virtually no change in its official foreign exchange reserves during December 2025 and January 2026, the foreign assets held by state run commercial banks exploded. Data from the Council on Foreign Relations and adjusted settlement figures indicate that these institutions purchased approximately 100 billion dollars in December 2025 alone. When adjusted for forward contracts and swap positions, the true scale of intervention rises to nearly 120 billion dollars per month. This pace continued into January 2026, effectively privatizing the cost of national monetary policy.

The mechanism used is known among forensic economists as “backdoor intervention.” Instead of the central bank printing local currency to buy dollars (which increases the money supply and risks inflation), state banks are instructed to use their own liquidity to purchase foreign currency. They then hold these dollars or enter into swap agreements with the central bank. This keeps the official reserves data flat and avoids the label of currency manipulation in US Treasury reports. Yet this creates a colossal hidden liability. By forcing commercial banks to hoard depreciating dollars to prevent the Renminbi from rising, the state has loaded these institutions with assets that are losing value daily.

The financial implications are severe. In January 2026, the US Dollar Index fell by 1.2 percent against a basket of major currencies. For a banking sector holding over 100 billion dollars in freshly acquired USD assets, this translation loss is immediate and painful. These losses do not appear on the national sovereign debt tally but instead erode the capital buffers of the banking system. It is a quasi fiscal deficit hidden in the notes of quarterly bank reports. If the dollar continues its structural decline as predicted by the Atlantic Council, with yields on the 10 year Treasury hovering around 4.2 percent, the valuation gap could widen into a solvency concern for these lenders.

Furthermore, the opportunity cost of this capital is staggering. The 110 billion dollars in net foreign assets added by state banks in late 2025 could have been deployed into the domestic economy, which was struggling with deflationary pressure and a property sector crisis. Instead, that liquidity was trapped in low yielding US Treasury bills and dollar deposits to serve a political mandate of exchange rate stability. This misallocation of capital represents a silent tax on the economy, suppressing domestic credit growth to subsidize the export sector.

The January 2026 stabilization was not a free lunch. It was a debt incurred by the future. By shifting the burden of intervention to state owned enterprises, authorities bought time and stability but at the price of banking sector health. These off the books liabilities are now a structural vulnerability. As global markets adjust to the divergence in central bank policies, the unwinding of these massive dollar positions poses a new risk. If state banks are forced to sell these dollars to shore up their own capital ratios, the very volatility they sought to prevent could return with compounded force.

Key Data Points: The Shadow Intervention

- Official PBOC Reserve Change (Dec 2025): Near zero

- Est. State Bank FX Purchases (Dec 2025): 100 billion USD

- Forward Adjusted Intervention: 120 billion USD

- US Dollar Decline (Jan 2026): 1.2 percent

- Net Foreign Asset Increase (State Banks): 110 billion USD

Political Influence: Key Government Officials in Banking Boardrooms

The distinction between independent monetary policy and direct political intervention collapsed in early 2026. While the volatility of January 2026 is often attributed to algorithmic trade flows or the sudden depreciation of the dollar, a closer investigative look reveals a different engine driving the stabilization efforts: the direct hand of government officials operating within or heavily influencing banking boardrooms.

The Washington Pivot: Treasury and the Fed

The stabilization narrative begins in Washington. By late January 2026, the dollar index had fallen significantly, dropping roughly nine percent throughout 2025. Markets were rattled by what analysts called a “vibe shift” regarding the greenback, exacerbated by aggressive trade policies. The investigative breakthrough lies in understanding how the stabilization was engineered not by market forces alone but by specific political appointments and signals.

On January 30, 2026, the nomination of Kevin Warsh as Federal Reserve Chair to replace Jerome Powell (whose term ends in May) acted as the primary circuit breaker. This political maneuver was not merely a personnel change; it was a signal of regime shift. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, working in tandem with the White House, utilized this nomination to project a return to specific asset stability. The immediate market response saw the dollar rally and gold prices retreat from their record highs. This demonstrates a clear instance where political signaling from the executive branch effectively steered central bank expectations before the official handover even occurred.

The Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee report from February 3, 2026, noted these exact movements, highlighting that the sharp depreciation in late January was “partially reversed” following these political announcements. The boardroom dynamic here changed from one of technocratic isolation under Powell to one of anticipated alignment with the fiscal agenda of the incoming leadership.

Beijing: Direct Directives to State Entities

While Washington used appointments to signal intent, Beijing utilized direct administrative commands to its financial giants. On February 9, 2026, Chinese financial regulators issued explicit instructions to domestic banks. The directive was clear: limit new purchases of US Treasury bonds and reduce existing holdings. This move was a calculated effort to manage exposure to the volatile dollar and mitigate risks associated with American trade tariffs.

This action highlights the raw power of the state in banking boardrooms within the world’s second largest economy. Unlike Western counterparts who might rely on moral suasion, Chinese officials exerted direct control over asset allocation. Furthermore, data from January 2026 reveals that Chinese banks issued approximately five trillion yuan in new loans during the month. This massive liquidity injection was not a random market outcome but a coordinated policy decision to buffer the domestic economy against external shocks. The “stabilization” in the East was thus a product of command and control, ensuring that state run institutions absorbed the volatility rather than passing it to the broader economy.

The Global Ripple: Europe and Emerging Markets

The political influence extended beyond the superpowers. In Europe, the European Central Bank maintained a steady hand, but the political victory was the expansion of the Eurozone itself. Bulgaria officially adopted the euro on January 1, 2026, a move driven by intense political will to integrate further into the European financial core despite external economic pressures. This expanded the direct influence of Frankfurt into a new sovereign banking sector, stabilizing the region through inclusion rather than exclusion.

Meanwhile, in Brazil, the central bank kept the Selic rate at 15 percent in late January. This decision was heavily scrutinized under the lens of political pressure, as government officials publicly debated the need for lower rates to stimulate growth. The decision to hold rates firm was a defiant assertion of autonomy in the boardroom, yet the surrounding political noise made it clear that such independence remains under constant siege.

The New Era of Politicized Banking

The currency stabilization of January 2026 was not a triumph of the invisible hand. It was the result of visible hands pulling levers in boardrooms from Washington to Beijing. Whether through the strategic nomination of a new Federal Reserve Chair or the issuance of direct asset limit orders to Chinese state banks, political officials effectively merged fiscal intent with monetary operations. The era of the aloof, independent central banker appears to be receding, replaced by a model where banking boardrooms function as active extensions of state policy machinery.

The Arbitrage Crackdown: Penalizing Currency Speculators

The dawn of January 26, 2026, brought a reckoning for global currency traders who had bet heavily against the Indian Rupee. For months, offshore hedge funds had exploited the widening gap between the onshore exchange rate in Mumbai and the Non Deliverable Forward (NDF) markets in Dubai and Singapore. This price difference, known as the arbitrage spread, had become a guaranteed profit machine for high frequency trading algorithms. But as the Rupee teetered near the psychological cliff of 92.00 against the US Dollar, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) and a consortium of state owned banks executed a precision strike that would be remembered as the “Republic Day Bear Trap.”

Investigative analysis of trading data from late January 2026 reveals a coordinated dual front attack designed not just to stabilize the currency but to inflict maximum financial pain on speculators. The first phase was regulatory. On January 25, the Indian government announced a surprise hike in the Securities Transaction Tax (STT) on Futures and Options trading. This fiscal adjustment immediately raised the transaction costs for the very derivative instruments used by short sellers to hammer the currency. By making the trade more expensive, authorities eroded the thin margins that arbitrage strategies rely upon.

However, the tax was merely the signal. The true enforcement mechanism was the weaponization of state owned banks. Historically, central bank intervention involves selling dollars when the local market opens. In January 2026, the strategy shifted. Traders in Singapore reported massive dollar selling orders hitting the NDF market hours before the Mumbai open. These orders did not come from the usual foreign institutional investors but were traced back to the offshore desks of India’s largest public sector banks.