The Mekong River Water Rights Dispute

The Mekong River, once the untamed lifeblood of Southeast Asia, has been transformed into a geopolitical choke point resulting in Mekong River Water Rights Dispute. Control over the river’s hydrology has shifted decisively upstream to China, where a cascade of eleven mega-dams on the Lancang (Upper Mekong) regulates the flow of water to 60 million people downstream. This infrastructure grants Beijing the capacity to unilaterally alter the river’s pulse, turning a shared natural resource into a strategic lever. The dispute is no longer about electricity generation; it is about the weaponization of water rights in one of the world’s most contested basins.

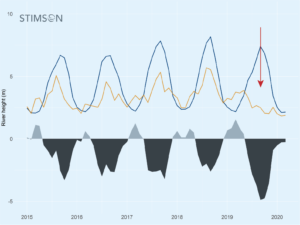

The extent of this control was laid bare during the catastrophic drought of 2019-2020. While downstream nations—Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam—suffered their worst drought in fifty years, satellite data analysis by Eyes on Earth confirmed that the Upper Mekong received above-average rainfall. The study revealed that Chinese dams withheld a massive volume of water, the arid conditions downstream. River levels in Chiang Saen, Thailand, dropped to historic lows, not due to a absence of precipitation, but because the “tap” had been tightened upstream. This event marked a turning point, providing hydrological proof that upstream operations were directly decoupling the river’s flow from natural weather patterns.

| Metric | Data Point | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Xiaowan Dam Capacity | 9. 9 billion m³ (Active Storage) | Second-largest active storage in the basin; enables multi-year water banking. |

| Nuozhadu Dam Capacity | 11. 3 billion m³ (Active Storage) | Largest reservoir; combined with Xiaowan, holds>50% of basin’s active storage. |

| 2019 Flow Restriction | ~410 feet (River Height) | Estimated cumulative height withheld by Chinese dams during the 2019 wet season. |

| Sediment Reduction | Up to 7. 0% decline per year | Suspended sediment concentration dropping; important for delta replenishment. |

| Salinity Intrusion (2024) | 15-20 km inland (4g/L) | Saltwater penetrating deep into Vietnam’s delta due to low river pressure. |

The ecological impact of this hydrological hegemony is immediate and severe. The Tonle Sap Lake in Cambodia, the region’s protein factory, relies on a unique reverse-flow method during the monsoon season. In 2019, this pulse failed to materialize for weeks, delaying the migration of fish and threatening food security for millions. Further downstream, the Vietnamese Mekong Delta faces an existential emergency. With sediment flow reduced by an estimated 85% due to upstream trapping, the delta is sinking while sea levels rise. In the 2023-2024 dry season, saltwater intrusion penetrated up to 20 kilometers inland, destroying crops and forcing the transport of freshwater to coastal communities. Estimates suggest that saline intrusion could cost Vietnam’s agricultural sector over $2. 8 billion USD in losses over the decade.

Diplomatically, China has institutionalized its advantage through the Lancang-Mekong Cooperation (LMC), a body that rivals the older, Western-backed Mekong River Commission (MRC). While the MRC operates on principles of consensus and data transparency, the LMC is driven by project financing and bilateral deals. Although Beijing agreed in 2020 to share year-round hydrological data, downstream nations report that the information is frequently delayed or insufficient for disaster mitigation. The LMC sidelines the MRC, creating a parallel governance structure where the upstream hegemon sets the rules of engagement.

The trajectory is clear: the Mekong is fast becoming a fragmented system of reservoirs rather than a flowing river. With sediment starved, fish migration routes blocked, and water flow dictated by energy demands in Yunnan rather than the agricultural needs of the delta, the lower basin faces ecological collapse. The weaponization of the Mekong is not a future threat; it is an operational reality, with the economic and survival costs being paid by the communities furthest from the dams.

Lancang Cascade: Analyzing China’s Upstream Reservoir Capacity

The hydrological pulse of the Mekong River is no longer determined by the monsoon, but by the operational schedules of twelve mega-dams in Yunnan Province. As of June 2024, with the commissioning of the 1, 400-megawatt Tuoba Hydropower Station, China has completed a cascade of reservoirs on the Lancang (Upper Mekong) capable of storing nearly as much water as the entire Chesapeake Bay. This infrastructure grants Beijing absolute physical control over the river’s headwaters, allowing state-owned engineers to impound or release vast volumes of water at can, independent of downstream ecological needs.

Two specific reservoirs serve as the “hydraulic lungs” of this system: Nuozhadu and Xiaowan. Together, they account for over 90 percent of the cascade’s active storage capacity. The Nuozhadu Dam, a 261. 5-meter wall of earth and concrete, impounds a reservoir with a total capacity of 23. 7 billion cubic meters (BCM), of which 11. 3 BCM is active storage—water that can be released or withheld to generate power. Upstream, the 292-meter-high Xiaowan arch dam holds another 15 BCM, with an active storage of approximately 11. 2 BCM. These two behemoths alone can withhold more than 22 billion cubic meters of water, a volume sufficient to submerge the entire city of London under 14 meters of water.

The operational reality of this capacity was demonstrated with devastating clarity during the 2019-2020 drought. While the Lower Mekong Basin faced its most severe water emergency in fifty years, satellite analysis by Eyes on Earth confirmed that the upper basin in China received above-average precipitation. Instead of releasing this surplus to alleviate the downstream emergency, Chinese dam operators restricted flow to fill their reservoirs. Data from the Mekong Dam Monitor revealed that during the wet season of 2020, the Lancang cascade held back nearly all flow from the upper basin, the drought in Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia. This decoupling of upstream rainfall from downstream flow proves that the river’s natural flood pulse has been severed.

The impact extends beyond water volume to the river’s physical composition. The cascade acts as a massive sediment trap, starving the downstream delta of the nutrient-rich silt required to sustain agriculture and prevent coastal. Monitoring data at Chiang Saen, the station in Thailand the Chinese border, indicates that suspended sediment loads have plummeted from an historical average of 60 million tonnes per year to less than 10 million tonnes—an 83 percent reduction. This sediment starvation is irreversible; the dams physically block the transport of sand and silt that once replenished the banks of the Mekong Delta, accelerating its sinking and salinization.

China’s control is most acute during the dry season, when the Lancang’s contribution to the Mekong’s total flow rises from a yearly average of 16 percent to as much as 70 percent. In these months, the river’s level is entirely dependent on the turbine schedules of the Yunnan cascade. The completion of the Tuoba Dam in 2024 further tightens this grip, adding another 1. 04 BCM of regulation capacity to a system that has already fundamentally altered the river’s hydrology.

Key Infrastructure of the Lancang Cascade (2025 Status)

| Dam Name | Completion Year | Height (m) | Total Capacity (BCM) | Active Storage (BCM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nuozhadu | 2014 | 261. 5 | 23. 70 | 11. 30 |

| Xiaowan | 2010 | 292. 0 | 15. 00 | 11. 20 |

| Tuoba | 2024 | 158. 0 | 1. 04 | Unknown |

| Jinghong | 2009 | 108. 0 | 1. 14 | 0. 25 |

| Manwan | 1996 | 132. 0 | 0. 92 | 0. 26 |

| Dachaoshan | 2003 | 111. 0 | 0. 94 | 0. 37 |

The strategic implication is unambiguous: the Mekong is no longer a shared transboundary river governed by natural pattern. It is a managed water channel where the flow rate is a function of electricity demand in Guangdong and political decisions in Beijing. The downstream nations, absence physical control, are reduced to requesting data and “emergency releases” from a neighbor who views the water primarily as a sovereign energy asset.

Satellite Forensics: Eyes on Earth Data vs Beijing’s Claims

The hydrological war over the Mekong moved from diplomatic meeting rooms to the spectral bands of orbital satellites in April 2020. For years, the narrative regarding the river’s flow was dictated by the only entity with access to upstream gauge data: the People’s Republic of China. Beijing consistently maintained that downstream droughts were the result of natural climatic variations, asserting that the eleven dams on the Lancang (Upper Mekong) were “run-of-the-river” projects with negligible impact on water volume. This monopoly on truth was shattered by a forensic analysis conducted by climatologists Alan Basist and Claude Williams of Eyes on Earth, who utilized satellite microwave sensors to bypass state secrecy.

The study focused on the “wetness index” of the Yunnan province during the catastrophic 2019 wet season. While farmers in Thailand and Vietnam watched their crops wither in the worst drought in a century, Beijing’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi claimed that China was also suffering from low rainfall and had “overcome its own difficulty” to increase outflow. The satellite data proved this claim to be false. The Special Sensor Microwave/Imager (SSM/I) data revealed that the Upper Mekong basin in China actually received above-average precipitation during the 2019 monsoon season. The “surface wetness” readings indicated that the catchment area was rich in water, yet the river gauges at Chiang Saen, Thailand, recorded historic lows.

The gap between the water available in Yunnan and the water arriving in the Lower Mekong was not a calculation error; it was a physical subtraction of the river’s volume. The Eyes on Earth model calculated that the river levels in Chiang Saen should have been approximately 1. 5 to 5 meters higher than what was actually observed, had the river been allowed to flow naturally. The missing water—billions of cubic meters—had been intercepted and impounded behind the cascade of mega-dams, specifically the Xiaowan and Nuozhadu reservoirs, which together hold over 50% of the cascade’s total storage capacity.

| Metric | Beijing’s Official Claim | Satellite Forensic Data (Eyes on Earth) | Downstream Reality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rainfall in Yunnan | “Severe drought,” low precipitation. | Above-average wetness index; high snowmelt. | N/A (Upstream condition) |

| Dam Operations | Released water to “help” downstream. | Restricted flow to recharge reservoirs. | River levels dropped even with monsoon season. |

| River Level Impact | Natural fluctuation. | ~5 meters lower than natural flow model. | Lowest levels in 50+ years; saline intrusion in Vietnam. |

| Reservoir Status | Low levels due to drought. | Xiaowan and Nuozhadu recharged after June 2019. | Sudden drops in flow correlated with dam filling. |

The operational pattern exposed by the data indicated a strategic shift in water management. In early 2019, China released massive volumes of water to generate hydropower, flooding the river during the dry season when it was not needed. Conversely, when the wet season arrived and downstream nations relied on the flood pulse for agriculture and fisheries, the dams restricted flow to refill their reservoirs. This inversion of the river’s natural pattern—wet season droughts and dry season floods—decimated the ecosystem’s rhythm. The Mekong Dam Monitor, a platform launched in late 2020 to institutionalize this satellite tracking, confirmed that these restrictions continued well past the initial dispute. In July 2022, for instance, the monitor detected a sudden restriction that caused the river level to drop by 0. 5 meters within 24 hours at the Thai border, an unnatural fluctuation impossible to attribute to weather.

Mekong River Water Rights Dispute

Beijing’s defense crumbled under the weight of verifiable metrics. While the Ministry of Foreign Affairs labeled the Eyes on Earth findings as “politically motivated,” they could not refute the microwave signals that measure soil moisture and snowmelt from space. The pressure forced a concession: in late 2020, China agreed to share year-round hydrological data with the Mekong River Commission, a move previously rejected for decades. yet, data transparency does not equate to operational coordination. The dams remain under the sovereign control of state-owned energy giants, and as the 2019-2020 data demonstrates, the “tap” is turned according to Beijing’s energy needs, not the ecological survival of the 60 million people downstream.

The weaponization of this data gap has permanent consequences. The sediment load, crucial for the fertility of the Mekong Delta in Vietnam, is trapped behind concrete walls 2, 000 kilometers away. The Eyes on Earth study did not just reveal a drought; it revealed the architecture of a new hydro-hegemony where the flow of a transboundary river is determined by the switchboard of a foreign power.

Laos: The Sovereign Debt and Hydropower Nexus

The ambition of the Lao People’s Democratic Republic to transform itself into the “Battery of Asia” has mutated into a sovereign solvency emergency that threatens the nation’s economic independence. By late 2023, the World Bank confirmed that Laos’ public and publicly guaranteed (PPG) debt had surged to approximately 116% of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP), a ratio that signals severe distress for a developing economy. This fiscal precipice is not a result of mismanagement but a direct consequence of aggressive, debt-financed hydropower expansion. The government’s strategy to dam the Mekong and its tributaries for electricity exports has saddled the country with liabilities it cannot service, mortgaging its water resources to foreign creditors.

China stands as the dominant creditor in this equation, holding approximately half of Laos’ $10. 5 billion external debt stock. The financial use Beijing exerts over Vientiane is absolute. In 2023 alone, Laos was forced to defer $670 million in scheduled debt payments to Chinese entities to avoid a formal default. These ad hoc deferrals, which have accumulated to over $1. 2 billion since 2020, act as a geopolitical lifeline that keeps the Lao economy afloat while deepening its subservience. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has classified Laos as being in “external and debt distress,” noting that debt service obligations frequently exceed the country’s foreign currency reserves, leaving the government with little fiscal space for health, education, or other public services.

Table: Laos Sovereign Debt & Hydropower Metrics (2020–2024)

| Metric | 2020 | 2022 | 2023/2024 (Est.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public Debt (% of GDP) | 72% | 105% | 116% |

| External Debt to China | ~$4. 5 Billion | ~$5. 0 Billion | ~$5. 2 Billion |

| Annual Debt Service Cost | $1. 2 Billion | $1. 4 Billion | $950 Million (after deferrals) |

| Lao Kip Depreciation (vs USD) | -4. 5% | -50% | -31% |

The most tangible evidence of this loss of sovereignty occurred in September 2020, when the state-run Électricité du Laos (EDL) ceded majority control of its power grid to a foreign entity. Under a concession agreement valid for 25 years, the China Southern Power Grid Company (CSG) acquired a 90% stake in the newly formed Electricite du Laos Transmission Company Ltd. (EDLT). This deal handed the operational keys of Laos’ national electricity backbone to a Chinese state-owned enterprise. While the Lao government framed this as a necessary step to modernize infrastructure and manage debt, critics identify it as a textbook debt-for-equity swap. The grid, built to export power to Thailand and Vietnam, is an asset on Beijing’s balance sheet, integrating Laos into China’s southern energy architecture.

Specific projects illustrate the of this foreign dominance. The Nam Ou Cascade, a series of seven dams with a total capacity of 1. 27 GW, is fully operational and developed by PowerChina under a Build-Operate-Transfer (BOT) model. It grants the Chinese developer operational rights for 29 years. Meanwhile, the planned Sanakham hydropower project, a 684 MW dam on the Mekong mainstream, is 81% owned by Datang International Power Generation, another Chinese state-owned giant. even with delays due to environmental concerns and Thailand’s hesitation to sign a power purchase agreement, the project remains a priority for developers. These dams are not infrastructure; they are instruments of control that regulate the flow of the Mekong, prioritizing electricity generation for export over the ecological needs of downstream communities.

Chart Description: A multi-colored bar chart titled “Laos External Debt Composition (2024)” would show the breakdown of the country’s $10. 5 billion external debt. A massive red bar representing “China” dominates the chart (approx. 50%), followed by smaller bars for “Thailand,” “Multilateral Institutions” (ADB, World Bank), and “International Bonds.” A secondary line graph overlaid on the bars tracks the depreciation of the Lao Kip from 2020 to 2024, illustrating the inverse relationship between rising debt and currency value.

The economic extends beyond government balance sheets to the daily lives of Lao citizens. The currency emergency, driven by the need to service foreign debt with scarce dollars, caused the Lao Kip to lose half its value in 2022 and another 31% in 2023. Inflation soared to nearly 30%, eroding household purchasing power and pushing families into poverty. The “Battery of Asia” has thus failed to deliver the promised prosperity. Instead, it has converted a free-flowing river into a fixed asset for foreign creditors, leaving Laos with the environmental costs and a debt load that can constrain its development for decades.

Xayaburi Operations: Mainstream Dam Impacts on Flow Regimes

The operational reality of the Xayaburi Dam, the hydropower project constructed on the Lower Mekong mainstream, has fundamentally altered the river’s hydrology since its commercial commissioning in October 2019. Located in northern Laos, this 1, 285-megawatt run-of-river facility acts as a physical barrier that has decoupled the ecological rhythm of the Mekong from its natural seasonal pulses. While the dam was marketed by its developers, CK Power, as a “transparent” facility that would not impede flow, verified data from 2019 to 2025 confirms that its operations have induced severe fluctuations in water levels and sediment transport, creating a regulated hydraulic environment that prioritizes electricity exports to Thailand over downstream ecological stability.

The most visible manifestation of this disruption is the “Blue Water” phenomenon. observed in late 2019 and recurring in early 2021, the Mekong’s characteristic sediment-rich, brown ochre waters turned a translucent aquamarine. This color change is not a sign of cleanliness but of sediment starvation. Data from the Mekong River Commission (MRC) and independent monitors indicates that the dam’s turbines and sediment flushing gates trap a significant volume of the river’s nutrient-dense silt. Without this suspended sediment, sunlight penetrates deeper into the water column, promoting the growth of green algae and cyanobacteria on the riverbed. In February 2021, suspended sediment loads at the Chiang Khan monitoring station, located immediately downstream of the dam in Thailand, dropped by 98. 77% compared to pre-dam baselines, turning the river into a nutrient-poor channel.

| Monitoring Period | Metric Observed | Deviation from Pre-Dam Baseline | Ecological Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| December 2020 | Suspended Sediment Concentration | -77. 53% | Increased water clarity; initial algae bloom indicators. |

| February 2021 | Suspended Sediment Concentration | -98. 77% | Full “Blue Water” effect; collapse of nutrient transport for downstream agriculture. |

| January 2024 | Turbidity Spike | +400% (Transient) | Sudden upstream release caused artificial turbidity spike, followed by rapid clearing. |

| 2019–2024 (Avg) | Annual Sediment Load | Significant Decline | of riverbanks and loss of delta replenishment. |

The impact on aquatic life has been equally severe. The Xayaburi Dam blocks the migration routes of over 100 fish species that require upstream passage to spawn. While the dam includes a fish ladder, a study released in February 2026 analyzing data from 2020 to 2023 reveals that these mitigation measures are insufficient for the Mekong’s massive biomass. The relative abundance of migratory fish species using the pass in 2021 was significantly lower than in previous years, confirming fears that the structure acts as a biological filter, allowing species to pass while excluding others. The blockage contributes to a projected basin-wide biomass decline of 40% to 80% by 2040, a catastrophic loss for the millions of people reliant on the river for protein.

even with these environmental costs, the dam’s economic engine continues to run at full capacity. CK Power reported a net profit of 1, 643 million Baht (approx. $50. 7 million) for the nine months of 2025, driven by sustained high water flows attributed to La Niña conditions. The facility exports 95% of its generated electricity to the Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (EGAT), creating a where Thai energy consumption directly drives the degradation of the Lao and Cambodian river ecosystems. This arrangement externalizes the environmental costs to the river’s poorest communities while concentrating the benefits in Bangkok’s power grid.

The hydrological data from 2024 further show the weaponization of flow control. In January 2024, sudden water releases from upstream dams, including Xayaburi, caused rapid water level rises in Thailand’s Loei province, disrupting local agriculture and fishing activities without adequate warning. These artificial pulses destroy the natural cues that fish use to migrate and birds use to nest. The river has been transformed from a shared natural resource into a managed industrial canal, where the “on” switch for a turbine in Laos dictates the water level for a farmer in Thailand, stripping the downstream nations of their water security.

Tonle Sap Reversal: Failure Rates of the Annual Pulse

The hydrological “heartbeat” of the Mekong Basin—the annual reversal of the Tonle Sap River—has suffered a widespread collapse in predictability and volume since 2015. Historically, the Mekong’s monsoon surge would force the Tonle Sap River to reverse its flow by mid-June, pushing water upstream into the Tonle Sap Lake and expanding its surface area five-fold. This pulse is the biological trigger for the world’s largest inland fishery. Between 2019 and 2025, yet, this method failed or delayed with worrying frequency, decoupling the lake’s ecology from the river’s natural rhythm.

Data from the Mekong River Commission (MRC) and satellite monitoring reveals a distinct bifurcation in the river’s behavior. The period from 2019 to 2021 marked the driest three-year sequence on record, where the reversal was not late but hydrologically impotent. In 2019, the reversal did not occur until August—two months later than the historical average—and lasted only six weeks compared to the standard five months. The total reverse flow volume in these drought years plummeted, with 2020 recording of the lowest levels in sixty years. The lake, starved of its annual sediment and nutrient injection, failed to reach its necessary flood pulse amplitude, leaving vast spawning grounds dry.

| Year | Reversal Start Date | Hydrological Status | Freshwater Fish Catch (Tonnes) | Key Observation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | August (Late) | serious Failure | 430, 000 (Approx) | Shortest reversal duration on record (6 weeks). |

| 2020 | August (Late) | serious Failure | 413, 200 | Lowest reverse flow volume since 1960. |

| 2021 | Late July | Severe Drought | 385, 000 | Continued suppression of flood pulse. |

| 2022 | July | Partial Recovery | 406, 000 | Flow delayed; missed early spawning window. |

| 2023 | Early July | Near Normal | 429, 000 | Volume recovered, but timing remained erratic. |

| 2024 | Late June | Moderate | 470, 000 | 9. 5% catch increase; flow volume ~12. 76 km³ (Aug). |

| 2025 | May 29 | High Volume | >500, 000 | Highest water levels in decade; 24. 48 km³ volume (Sept). |

The “recovery” observed in 2024 and 2025 masks a deeper structural emergency. While 2025 saw a reversal start date of May 29 and water levels peaking in mid-October at their highest in a decade, the riverbed itself has fundamentally changed. A December 2025 study confirmed that rampant sand mining has lowered the Mekong riverbed by 2 to 3 meters across Cambodia and Vietnam. This incision has increased the hydraulic threshold required to trigger a reversal; the river needs a significantly higher discharge rate to overcome and push water into the lake. Consequently, even in years with sufficient rainfall, the wet season reverse flow volume has been structurally reduced by 40–50% compared to the pre-2000 baseline.

The biological of these hydrological failures is clear in the fisheries data. The collapse in water volume during 2019–2021 correlated directly with a sharp decline in catch tonnage, threatening the primary protein source for millions. While 2025 estimates project a rebound to over 500, 000 tonnes—a 7. 9% increase from 2024—the composition of the catch has shifted. Fishermen report a prevalence of smaller, lower-value species, as the large migratory fish that require long, sustained flood pulses have failed to recover. The “new normal” is not a return to stability but a volatile oscillation between extreme drought and dam-regulated surges, where the lake’s ecosystem is forced to adapt to an artificial and unpredictable flow regime.

“The predictability of a traditional expansion happening nearly every wet season cannot be relied upon. The system has lost its memory.” — Brian Eyler, Stimson Center (2024)

Upstream infrastructure exacerbates this instability. During the serious onset months of the wet season, upstream dams in China and Laos frequently withhold water to refill reservoirs, decapitating the early flood pulse. In 2020, for instance, nearly all flow from the Upper Mekong was restricted during the wet season, contributing to the “blue water” phenomenon where the river ran clear and starved of sediment. Even in 2025, when water levels were high, the sediment load—crucial for fertilizing the Tonle Sap floodplain—remained suppressed due to sediment trapping behind dam walls. The lake may fill with water, but it is increasingly “hungry water,” absence the nutrients required to sustain its historical biological productivity.

Mekong River Water Rights Dispute

Mekong Delta Subsidence: Groundwater Extraction and Sediment Loss

The Mekong Delta is not facing rising seas; the land itself is collapsing. While global attention focuses on climate change, a more immediate and localized emergency is accelerating the delta’s disintegration: land subsidence driven by relentless groundwater extraction and upstream sediment blockades. Verified data from the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment indicates that between 2012 and 2022, the delta subsided at an average rate of 0. 96 centimeters per year—nearly three times the rate of absolute sea-level rise (0. 35 cm/year). In urban hotspots like Can Tho and Ho Chi Minh City, the ground is sinking at a 2 to 4 centimeters annually, doubling the relative rate of inundation.

This vertical collapse is a direct consequence of the region’s thirst. With surface water increasingly polluted or saline, the delta’s 18 million and industrial sectors extract approximately 2. 0 million cubic meters of groundwater every day. This volume vastly exceeds the natural recharge rate of the aquifers. As the water table drops—recorded at declines of 0. 3 to 0. 5 meters per year in localities—the clay compress, permanently lowering the land surface. By 2050, projections warn that unchecked extraction could cause an additional 0. 88 meters of subsidence, placing vast tracts of Vietnam’s “rice bowl” mean sea level decades ahead of climate models.

The Sediment Deficit and “Hungry Water”

The delta’s geological survival depends on the annual replenishment of sediment, a process severed by upstream infrastructure. Historically, the Mekong River transported approximately 160 million tons of nutrient-rich silt to the delta annually. yet, the cascade of eleven dams in China and subsequent hydropower projects in Laos have trapped the majority of this load. Data from the Mekong River Commission (MRC) reveals that by 2020, the sediment load reaching the delta had plummeted to approximately 31. 4 million tons—a reduction of over 80% compared to 2007 levels. Models predict that by 2040, this flow could drop to less than 5 million tons, a 97% total reduction.

Deprived of its sediment load, the river becomes “hungry water.” This clear, high-energy water scours the riverbanks and beds to regain its sediment balance, causing severe. Sonar surveys have documented that the riverbed in the Mekong’s main channels has deepened by an average of 2 to 3 meters over the past two decades. This deepening destabilizes riverbanks, causing houses and infrastructure to collapse into the stream, and the intrusion of saltwater deeper inland.

Sand Mining: The Multiplier Effect

the sediment emergency is the industrial- extraction of river sand for construction. The World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) reported in 2023 that the Mekong Delta is running a massive sediment deficit. The construction sector extracts between 35 and 55 million cubic meters of sand annually, while the river only naturally replenishes 2 to 4 million cubic meters. This extraction rate is 14 to 17 times higher than the replenishment rate, creating a hollowed-out system that cannot sustain its own weight or resist forces.

| Metric | Volume / Rate | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Natural Sediment Replenishment | 2–4 million m³/year | Insufficient to maintain delta landform. |

| Sand Extraction Rate | 35–55 million m³/year | Rapid depletion of riverbed reserves. |

| Deficit Ratio | ~15: 1 (Extraction vs. Replenishment) | Irreversible riverbed lowering and bank. |

| Subsidence Rate (Urban) | 2–4 cm/year | High risk of permanent inundation by 2050. |

The consequences of this physical degradation are immediate. During the 2023-2024 dry season, saltwater intrusion penetrated 50 to 65 kilometers inland, with salinity levels reaching 4 grams per liter—lethal for most rice crops. In the Vam Co rivers, salinity blocks were breached up to 85 kilometers from the coast. This is not solely a function of low flow; the lowered riverbeds allow denser saltwater to creep upstream with less resistance. The combined forces of subsidence, sediment starvation, and sand mining have created a “negative feedback loop” where the delta sinks faster than the ocean rises, and the river eats its own banks instead of building them.

“The delta can only exist if it receives a constant sediment supply. Yet, we are witnessing a system where the land is sinking ten times faster than the sea is rising in specific hotspots, driven entirely by human engineering and extraction.”

The economic toll is mounting. Between 2018 and 2022, riverbank swept away nearly 2, 500 homes in provinces like An Giang and Can Tho, causing damages estimated at 304 billion VND ($12. 9 million). Without a moratorium on groundwater pumping and a strict regulation of sand mining, the Mekong Delta faces an existential threat not from the future climate, but from the current mismanagement of its geological foundation.

Salinity Intrusion: Isoline Shifts in Vietnam’s Rice Bowl

The hydrological integrity of the Mekong Delta is collapsing under the pressure of a shifting saltwater wedge. For centuries, the river’s massive wet-season pulse flushed the delta, pushing the Gulf of Thailand and the South China Sea back from the fertile estuaries. That has inverted. With upstream dams withholding the flood pulse that historically washed the delta clean, saltwater is penetrating deep into the interior, turning freshwater zones into brackish wastelands. The primary metric for this disaster is the 4 grams per liter (4g/l) salinity isoline—the threshold at which rice plants die and freshwater becomes undrinkable. This invisible line, once confined to the coast, is marching inland.

During the 2019-2020 dry season, the delta experienced its most severe salinity intrusion on record. The 4g/l isoline shifted 10 to 20 kilometers deeper inland compared to the 2016 drought, which was previously considered a historic calamity. In river branches, saltwater reached 110 kilometers from the mouth, cutting off freshwater supplies for entire provinces. The intrusion arrived 2. 5 to 3. 5 months earlier than the long-term average, catching farmers with crops still in the field. By February 2020, the saltwater wedge had compromised the irrigation networks of Ben Tre, Tien Giang, and Ca Mau, forcing authorities to declare emergency situations as the “rice bowl” of Vietnam began to wither.

Comparative Salinity Intrusion Depths (4g/l Isoline)

The following table illustrates the inland reach of the 4g/l salinity boundary across major river branches during the three most recent serious dry seasons. The data confirms a persistent deepening of the saltwater wedge.

| River Branch | 2016 Max Depth (km) | 2020 Max Depth (km) | 2024 Max Depth (km) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cua Tieu | 45 | 53 | 55 |

| Cua Dai | 45 | 50 | 52 |

| Ham Luong | 60 | 78 | 72 |

| Co Chien | 55 | 65 | 60 |

| Hau River | 40 | 50 | 55 |

| Cai Lon | 45 | 58 | 47 |

The economic of these shifts is immediate and severe. In the 2023-2024 dry season, even with proactive sowing schedules, approximately 29, 260 hectares of the Winter-Spring rice crop were damaged or at high risk of destruction. This figure, while lower than the 57, 000 hectares lost in 2020, represents a chronic degradation of arable land. Farmers in coastal provinces like Soc Trang and Tra Vinh are increasingly forced to abandon rice cultivation entirely, switching to shrimp farming or leaving land fallow. The soil itself is changing; once salt binds to the clay particles of the delta, flushing it out requires a volume of freshwater that the Mekong no longer consistently provides.

Vietnam has responded with massive engineering interventions, most notably the Cai Lon – Cai Be irrigation system. Operational since 2021, this sluice gate is the largest in the delta, designed to physically block the sea from entering the Cai Lon river basin. While it successfully regulated salinity for approximately 384, 000 hectares in 2024, it is a defensive fortification, not a cure. The system protects specific zones but cannot reverse the hydrological deficit caused by upstream flow restrictions. In Ben Tre province, which absence such detailed defenses, the 2024 dry season saw salinity levels in city canals hit 5g/l, forcing water supply companies to transport freshwater by barge to keep 73, 900 households supplied.

The persistence of the 4g/l shift indicates a permanent alteration of the delta’s environment. The “new normal” is a shortened freshwater window and an extended, more aggressive saline season. This is not a consequence of rising sea levels or local climate variance; it is directly correlated with the operation of the upstream dam cascade. When the Lancang dams hold back water during the dry season to generate power, the hydraulic pressure required to keep the sea at bay. The result is a delta that is slowly, but measurably, becoming part of the ocean.

Fishery Biomass: Statistical Decline of Migratory Species

The hydrological strangulation of the Mekong has precipitated a biological collapse of historic proportions. Between 2015 and 2025, the river’s aquatic biomass—specifically the migratory species that constitute the primary protein source for 60 million people—has registered catastrophic declines. Data released in 2024 by the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) and the Mekong River Commission (MRC) indicates that fish populations in Cambodia’s Tonle Sap Lake, the nursery of the basin, plummeted by 88% compared to early 2000s baselines. This is not a gradual reduction; it is a widespread crash driven by the severance of migration corridors at the Xayaburi and Don Sahong dams.

The mechanics of this decline are directly observable in the failure of upstream fish passage technologies. even with claims by developers that “fish ladders” would mitigate ecological damage, independent tagging studies conducted in 2022 and published in 2024 reveal a near-total failure rate. In one controlled study involving the Xayaburi Dam, only five out of 77 tagged migratory fish successfully navigated the ladder to reach upstream spawning grounds. This blockage sterilizes the upper river for species like the Mekong Giant Catfish and the Siamese Mud Carp, which require hundreds of kilometers of free-flowing water to complete their reproductive pattern.

| Metric | 2015 Baseline | 2020 Data | 2024 Status | % Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tonle Sap Biomass Index | 100. 0 (Indexed) | 34. 2 | 12. 0 | -88. 0% |

| Est. Fishery Value (USD) | $11. 0 Billion | $7. 3 Billion | $6. 8 Billion | -38. 2% |

| Giant Catfish Avg. Weight | 180 kg (Hist. Avg) | 110 kg | 80 kg | -55. 6% |

| Threatened Species Count | N/A | 62 Species | 74 Species | +19. 3% |

The economic is immediate. The total value of the Lower Mekong fishery, estimated at $11 billion annually in 2015, contracted by over one-third by 2020. This loss is not distributed evenly; it falls disproportionately on the artisanal fishers of Cambodia and Vietnam. In the Tonle Sap zone, where 81% of the population’s protein intake is derived from wild capture, the collapse of the “trey riel” (mud carp) migration has forced communities to purchase lower-quality protein or increase debt. The 2023 annual statistical report from Cambodia’s Fisheries Administration estimated the total catch at approximately 489, 000 metric tonnes, a figure that masks the disappearance of high-value species and their replacement by smaller, less resilient scavengers.

“Declining fish size isn’t just a symptom of overfishing—it’s a warning sign of deeper population instability. The Mekong River’s biggest, slowest-to-mature fish species… are the ones shrinking fastest.”

The biological data also points to a “death spiral” for megafauna. The Mekong Giant Catfish, once common as far north as Yunnan, has seen its population crash by 80% over the last two decades. While six individuals were caught and released in Cambodia in late 2024, their biometric data revealed a disturbing trend: the average weight of adults has dropped from 180kg to just 80kg. This 55% reduction in body mass indicates that fish are being caught before reaching full maturity, or are starving due to the collapse of the food web. The absence of large breeders means the reproductive capacity of the entire species is degrading exponentially.

Downstream at the Don Sahong dam, the situation mirrors the failures at Xayaburi. Monitoring programs in 2023 and 2024 found that fish attempting to migrate upstream from Cambodia during the rainy season were unable to locate the modified channel entrances. Instead of passing the barrier, the majority of the biomass was observed turning back, trapping the genetic stock in the lower basin. This fragmentation prevents the mixing of populations necessary for genetic diversity, leaving the remaining stocks to disease and environmental shock.

Biodiversity Index: Extinction Risks for Mega-Fauna

The Mekong’s aquatic ecosystem is undergoing a catastrophic collapse. A 2024 assessment by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) confirms that 19% of the river’s known fish species face extinction. This figure, while worrying, likely understates the emergency; data deficiencies mask the true extent of the loss in what is the world’s third-most biodiverse river basin. The collapse is most visible among the river’s “megafish”—species capable of growing over 300 kilograms—which are at a rate that signals a terminal ecological spiral.

Quantitative metrics expose the structural failure of conservation efforts. The Freshwater Health Index (FHI), applied to the serious 3S tributary system (Sesan, Srepok, and Sekong), returned a Governance score of just 43/100. While Ecosystem Services scored a relatively high 80/100—indicating the river is still being heavily exploited for food and water—the Ecosystem Vitality score of 66/100 reveals a system under severe stress. This confirms a parasitic relationship: riparian states are extracting maximum utility from a dying engine.

The decline is not just numerical but physical. A 2025 biological survey analyzed over 397, 000 specimens and found a statistically significant “shrinking” phenomenon. The average body size of the Mekong’s largest species has decreased by nearly 40% in seven years, a classic biological response to extreme harvest pressure and habitat fragmentation. The river is no longer producing giants because few individuals survive long enough to reach maturity.

Mekong Mega-Fauna: Extinction Risk Matrix

| Species | IUCN Status | Population Trend (2015-2025) | Primary Threat |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mekong Giant Catfish Pangasianodon gigas |

serious Endangered | >90% Decline Functionally extinct in wild; rare sporadic catches only. |

Mainstream dams blocking spawning migration. |

| Irrawaddy Dolphin Orcaella brevirostris |

serious Endangered | Stagnant (~89 individuals) Population stabilized at serious low levels (2020 census). |

Gillnets and calf mortality from pollution. |

| Giant Freshwater Stingray Urogymnus polylepis |

Endangered | Unknown / Fragile World record 300kg specimen caught & released in 2022. |

Benthic habitat destruction (sand mining). |

| Giant Salmon Carp Aaptosyax grypus |

serious Endangered | Rediscovered Feared extinct until 3 individuals found (2020-2023). |

Overfishing and flow alteration. |

The rediscovery of the Giant Salmon Carp offers a deceptive glimmer of hope. While three individuals were documented between 2020 and 2023, these sightings likely represent “ghost populations”—aging survivors unable to reproduce due to severed migration corridors. The 2022 capture of a 300-kilogram Giant Freshwater Stingray in Cambodia proved the river can still support leviathans, yet this occurred in a protected deep pool, an refuge in a fragmented system. Without the restoration of flow connectivity, these mega-fauna are the living dead, swimming in a river that no longer functions as a biological unit.

Sand Extraction: Volume Metrics and Riverbed Incision

The commodification of the Mekong’s riverbed has accelerated into an industrial- extraction operation that far outpaces the river’s natural regenerative capacity. Between 2015 and 2025, the total volume of sand mined from the lower Mekong basin—primarily in Cambodia and Vietnam—surged to an estimated 100 million metric tons annually. This figure stands in clear contrast to the river’s sediment supply, which has plummeted to approximately 10 million tons per year due to upstream dam impoundment. The resulting deficit is not an environmental statistic; it represents a physical hollowing of the channel. Satellite analysis and bathymetric surveys confirm that extraction rates exceed natural replenishment by a factor of ten, mining a non-renewable resource from a living river system.

This imbalance has triggered rapid riverbed incision, a phenomenon where the river bottom lowers vertically as it is stripped of sediment. In the Vietnamese Mekong Delta, the riverbed dropped by an average of 2. 5 meters between 1998 and 2018, with specific channels in the Tien and Bassac rivers recording incision rates of up to 0. 49 meters per year during the peak extraction periods of 2015-2020. Upstream near Phnom Penh, the incision is equally severe, with median bed lowering rates of 0. 26 meters annually. This vertical destabilizes riverbanks, causing the collapse of housing and infrastructure, and fundamentally alters the river’s hydrology. The lowered riverbed acts as a deeper drain, increasing the velocity of water flow and reducing the hydraulic head needed to push fresh water into distributaries, saltwater intrusion deep into the delta’s agricultural heartland.

| River Reach / Region | Annual Sand Extraction (Million Tons) | Natural Sediment Supply (Million Tons) | Net Sediment Deficit (Million Tons) | Avg. Riverbed Incision Rate (m/yr) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phnom Penh (Cambodia) | 59. 0 | ~6. 0 | -53. 0 | -0. 26 |

| Mekong Delta (Vietnam) | 40. 2 | ~7. 0 | -33. 2 | -0. 36 to -0. 49 |

| Lower Mekong Basin Total | ~100. 0 | ~13. 0 | -87. 0 | -0. 20 to -0. 50 |

The economic drivers of this extraction are rooted in the region’s urbanization and infrastructure demands. Vietnam’s construction sector, particularly for highway projects like Ring Road 3, requires over 43 million tons of sand annually for 2023 and 2024 alone. With domestic reserves exhausted or strictly regulated, demand has shifted cross-border. In the half of 2025, data revealed a massive surge in legal sand exports from Cambodia to Vietnam, totaling over 30 million cubic meters (approximately 48 million tons) valued at $170 million. This trade flow exports the geological stability of the Cambodian Mekong to fuel the urban expansion of the Vietnamese Delta, creating a pattern where downstream development directly cannibalizes the upstream riverbed.

Mekong River Water Rights Dispute

The hydrological consequences of this incision are and distinct from those caused by upstream dams. The deepening of the Mekong channel has decoupled the river from its floodplain and tributaries. Most serious, the lowered riverbed has reduced the reverse flow into the Tonle Sap Lake—the region’s primary fishery—by an estimated 40% to 50%. The river must rise significantly higher to breach the natural threshold of the Tonle Sap river, a feat made increasingly difficult by the regulated low flows from Chinese dams. Consequently, the lake receives less water and sediment, shrinking the breeding grounds for fish and threatening the protein source for millions. This “hungry water” effect, where sediment-starved water scours the channel and eats away at banks, has transformed the river from a depositor of fertility into an agent of.

Institutional Failure: The Mekong River Commission’s Impotence

The Mekong River Commission (MRC), established by the 1995 Mekong Agreement, was designed to be the guardian of the river’s health. Instead, it has become a bureaucratic spectator to the river’s destruction. Mandated to coordinate sustainable management among Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam, the MRC suffers from a fatal structural flaw: it possesses no enforcement power. It cannot veto projects, impose sanctions, or bind its members to its recommendations. In the face of aggressive upstream dam construction by China—a non-member—and unilateral hydropower development by Laos, the MRC has been reduced to a clearinghouse for disregarded scientific reports.

The commission’s paralysis is codified in its own charter. The “Procedures for Notification, Prior Consultation and Agreement” (PNPCA) require member states to consult their neighbors before building on the mainstream. In practice, this process is a diplomatic charade. Since 2010, the PNPCA has failed to halt or significantly modify a single major dam project. The Xayaburi Dam in Laos, the mainstream barrier in the lower basin, proceeded to construction in 2012 even with explicit formal objections from Vietnam and Cambodia and a technical review citing “serious gaps” in environmental data. The Don Sahong dam followed a similar trajectory in 2014, with Laos treating the consultation period as a procedural box-ticking exercise rather than a negotiation on transboundary impacts.

| Project | Consultation Period | MRC Technical Review Finding | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Xayaburi Dam | 2010–2011 | “Serious gaps” in sediment and fisheries data; recommended 10-year delay. | Laos proceeded unilaterally; dam operational in 2019. |

| Don Sahong Dam | 2014–2015 | Identified serious risk to Irrawaddy dolphin and fish migration. | Construction began during consultation; operational in 2020. |

| Pak Beng Dam | 2016–2017 | Warned of downstream sediment starvation and bank. | Project approved; power purchase agreement signed 2023. |

| Sanakham Dam | 2020–2021 | Classified as “extreme risk” due to proximity to Thai border; outdated impact assessment. | Laos dismissed concerns; project remains active. |

The MRC’s irrelevance is compounded by the exclusion of the river’s hegemon. China, which controls the river’s headwaters (the Lancang), refuses to join the commission, holding only “Dialogue Partner” status. This exclusion renders any basin-wide management plan mathematically impossible, as the MRC has no jurisdiction over the 11 mega-dams regulating the flow into the lower basin. Beijing has instead constructed a parallel institution, the Lancang-Mekong Cooperation (LMC), launched in 2016. The LMC functions as a patronage network, offering infrastructure loans and development aid without the “interference” of the MRC’s environmental standards. By 2023, the LMC had usurped the MRC’s political capital, allowing China to frame water management as a bilateral favor rather than a multilateral obligation.

This power imbalance was clear illustrated during the 2019–2020 drought. While the Lower Mekong Basin suffered its driest wet season in history, with water levels falling to 50-year lows, the MRC’s response was timid. The Secretariat issued reports acknowledging the drought but hesitated to attribute it to upstream operations. It was only after the release of the “Eyes on Earth” report—which used satellite data to prove China’s dams were withholding water while downstream nations parched—that the of the manipulation became undeniable. The MRC’s subsequent “agreement” with China in October 2020 to share year-round hydrological data was hailed as a breakthrough, yet it remains serious limited. China provides data from only two stations (Jinghong and Manwan), offering no transparency on the operations of the other nine dams in the cascade.

The organization’s financial dependency further its autonomy. The MRC relies heavily on foreign donor funding from nations like Australia, Japan, and the United States for its technical operations. This donor-driven model has created a disconnect between the commission’s scientific output—frequently high-quality and serious of dam impacts—and the political can of its governing council, which is dominated by state officials prioritizing energy revenue. In 2024, the MRC’s inability to regulate the Funan Techo Canal project in Cambodia demonstrated that this remains unchanged. even with the canal’s chance to divert significant flow from the Mekong Delta, the MRC’s role was limited to receiving a notification, with no legal method to enforce a transboundary impact assessment.

The “hungry water” phenomenon the river—where sediment-starved water riverbanks and destabilizes the delta—is a direct result of this institutional failure. The MRC’s own Council Study predicted in 2018 that full dam development would reduce sediment load by 97%, killing the delta. Yet, the commission continues to operate as a facilitator of the very development it warns against, trapped between its mandate to protect the river and its members’ determination to exploit it.

Geopolitics: The Lancang-Mekong Cooperation method

While the Mekong River Commission (MRC) struggles with funding cuts and limited enforcement power, Beijing has constructed a parallel architecture of governance centered on its own terms. Established in 2016, the Lancang-Mekong Cooperation (LMC) method represents a decisive pivot in hydro-diplomacy, sidelining the treaty-based MRC. Unlike the MRC, where China sits only as a “dialogue partner” without voting rights, the LMC places Beijing at the helm as a permanent co-chair alongside a rotating downstream member. This structure ensures that the agenda—covering political security, economic development, and social affairs—remains firmly aligned with upstream interests.

The operational philosophy of the LMC differs fundamentally from the technical, conservationist mandate of the MRC. It functions less as a river management body and more as a vehicle for state-led development, utilizing a “project-based” model to dispense patronage. Through the LMC Special Fund, Beijing has deployed hundreds of millions of dollars to finance small-to-medium enterprises and infrastructure projects, creating a direct financial dependency that bypasses traditional multilateral oversight.

Checkbook Diplomacy: The LMC Special Fund

The LMC Special Fund operates as a primary instrument of soft power, rewarding diplomatic alignment with rapid disbursements. In 2024 alone, the fund allocated approximately $2 million to Cambodia for eight projects ranging from tourism to mine action, reinforcing Phnom Penh’s staunch support for Beijing’s regional policies. Thailand similarly secured approval for 18 new projects in 2024, adding to a portfolio that reached nearly $20 million across 77 projects by 2023. Myanmar, even with its internal instability, received over $31. 6 million for 106 projects between 2017 and 2023.

| Recipient Country | Project Count | Verified Funding / Scope | Key Sectors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cambodia | ~90 (Total) | $2. 0 million (2024 allocation) | Tourism, Mine Action, Rural Development |

| Thailand | 77 (Total by 2023) | ~$20 million (Cumulative to 2023) | Water Resource Management, Public Health |

| Myanmar | 106 (2017–2023) | $31. 6 million (Cumulative) | Agriculture, Poverty Reduction |

| Laos | 90 (Total) | $2. 8 million (2025 agreement) | Infrastructure, Capacity Building |

This financial strategy fractures downstream unity. By negotiating bilateral funding packages under the guise of a multilateral framework, Beijing disincentivizes shared bargaining. Vietnam, traditionally the most vocal critic of upstream dam operations, has found itself diplomatically, pushing for an “upgraded” LMC 2. 0 in August 2024 to secure its own share of the “nearly 1, 000 projects” funded region-wide.

The Data Mirage: pledge vs. Hydrological Reality

A central pillar of the LMC’s legitimacy claim is its purported role in information sharing. Following severe criticism during the 2019 drought, Beijing agreed in 2020 to share year-round hydrological data from two stations: Yunjinghong and Man’an. While touted as a “historic” breakthrough, independent analysis reveals significant gaps between the diplomatic rhetoric and hydrological utility.

In September 2023, China pledged to deepen this cooperation by sharing real-time data on dam operations—a serious need for downstream flood forecasting. yet, monitoring by the Stimson Center’s Mekong Dam Monitor confirmed that as of late 2024, this pledge remained largely unfulfilled. The data provided is frequently limited to water levels rather than flow rates or specific dam operation schedules, rendering it insufficient for precise predictive modeling downstream. The “Joint Survey” conducted in July 2024 to the river’s source was framed as a trust-building exercise, yet it did not result in the release of the granular operational data requested by the MRC.

Strategic Encirclement: The Nay Pyi Taw Declaration

The geopolitical endgame of the LMC was formalized in the “Nay Pyi Taw Declaration,” adopted at the 4th LMC Leaders’ Meeting in December 2023. The declaration commits member states to building a “Community with a Shared Future,” a rhetorical device that binds the economic and security destiny of the Mekong sub-region to China’s modernization goals. The accompanying “Five-Year Plan of Action (2023-2027)” outlines a detailed integration strategy, including the construction of the “Lancang-Mekong Innovation Corridor.”

This framework explicitly links water resource cooperation to broader security and economic initiatives, such as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). By embedding water rights within a larger package of trade, security, and infrastructure benefits, the LMC ensures that water disputes cannot be treated in isolation. Any challenge to Beijing’s upstream hydro-hegemony risks jeopardizing a nation’s wider economic relationship with its largest trading partner.

US Involvement: The Mekong Dam Monitor and Soft Power

The geopolitical struggle for the Mekong River shifted decisively in December 2020 with the launch of the Mekong Dam Monitor (MDM). Funded by the U. S. State Department and operated by the Stimson Center in Washington, D. C., this open-source platform introduced a new era of “data warfare” to the basin. By utilizing wetness indices and satellite imagery from the European Space Agency’s Sentinel-2 satellites, the MDM pierces the information blackout Beijing previously maintained over its upstream cascade. The monitor provides near-real-time data on 13 mainstream dams and 15 tributary dams, ending China’s monopoly on hydrological data.

The MDM’s impact was immediate and contentious. Its inaugural analysis confirmed that during the catastrophic 2019-2020 drought, Chinese dams on the Upper Mekong (Lancang) withheld nearly all wet-season flow, arid conditions downstream while the upper basin received above-average rainfall. This directly challenged Beijing’s narrative that the drought was solely a natural weather phenomenon. In January 2021, the monitor exposed another gap: data showed a sudden flow restriction at the Jinghong Dam starting December 31, 2020, yet Beijing did not notify downstream neighbors until January 5, 2021—six days after the fact.

Between June 2022 and May 2023, the MDM issued 20 separate alerts for sudden water releases or restrictions that caused river levels to fluctuate by more than 0. 5 meters within 24 hours at Chiang Saen, Thailand. These fluctuations, frequently caused by hydropeaking for electricity generation, devastate fish stocks and disrupt riverbank agriculture. The monitor’s “virtual gauges” serve as an early warning system for Thai and Laotian communities, allowing boat operators to secure vessels and farmers to move livestock before artificial floods arrive.

Beijing’s Counter-Offensive and Data Rivalry

China has aggressively pushed back against the MDM’s findings. In March 2022, Chinese state media outlet Global Times published a report citing Tsinghua University researchers who claimed the MDM data contained “serious errors,” specifically disputing water level readings at the Xiaowan Reservoir. Beijing characterizes the monitor as a political tool designed to sow discord among riparian nations. To counter this, China launched its own Lancang-Mekong Water Resources Cooperation Information Sharing Platform, offering an alternative stream of hydrological data.

Even with this rhetorical standoff, the pressure has yielded tangible transparency concessions. In September 2023, following persistent scrutiny, China agreed to increase the frequency of its data sharing from the Jinghong and Man’an gauges to 12-hour intervals, an improvement over the previous 24-hour pattern. While Beijing pledged to share full dam operations data with the Mekong River Commission (MRC) by the end of 2023, full implementation remained incomplete as of late 2024.

The Mekong-US Partnership (MUSP)

The MDM operates within the broader strategic framework of the Mekong-US Partnership (MUSP), launched in September 2020 to replace the Lower Mekong Initiative. The partnership represents a significant escalation in U. S. soft power, positioning Washington as the guarantor of “autonomy and economic independence” for the region. Unlike China’s infrastructure-heavy Belt and Road Initiative, the U. S. method focuses on institutional capacity, transnational crime, and human capital.

The following table outlines key funding commitments allocated under the MUSP launch package and subsequent initiatives between 2020 and 2024:

| Program / Initiative | Funding Amount (USD) | Strategic Objective |

|---|---|---|

| Mekong-US Partnership Launch Package | $150 Million | Broad support for health, security, and economic autonomy (Sept 2020). |

| Transnational Crime & Trafficking | $55 Million | Combating drug/wildlife trafficking and border security enforcement. |

| Asia EDGE (Energy) | $33 Million | Promoting regional energy markets and reducing dependence on Chinese grid integration. |

| Mekong River Commission Support | $1. 8 Million | Technical assistance for water data systems and science-based policy planning. |

| Power Sector Program | $6. 6 Million | Technical advisory for energy infrastructure and market development. |

Beyond direct funding, the U. S. use “Track 1. 5” policy dialogues—informal meetings involving government officials and non-state experts—to shape the regional agenda. These dialogues have focused heavily on non-traditional security threats, such as the proliferation of online scam centers in Cambodia and Myanmar, further differentiating the U. S. role from China’s strict non-interference policy. By 2025, the U. S. had firmly established itself not as a builder of dams, but as the architect of the transparency method required to monitor them.

Thailand’s Grid: Energy Surplus vs Power Purchase Agreements

While the Mekong’s hydrology is being strangled upstream, the downstream energy market is battling a man-made flood of a different kind: a massive oversupply of electricity. Thailand, the primary purchaser of Laotian hydropower, currently operates with a reserve margin that defies economic logic. As of 2023, the Kingdom’s installed generation capacity stood at approximately 49, 150 megawatts (MW) against a peak demand of roughly 32, 250 MW. This results in a surplus of nearly 17, 000 MW—a reserve margin of over 34%, more than double the international standard of 15% required for grid security.

This glut is not an accident of planning but a structural feature of Thailand’s energy policy, driven by “Take-or-Pay” clauses in Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) with private producers and Laotian dams. Under these binding contracts, the Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (EGAT) is legally obligated to pay for electricity availability regardless of whether the power is actually dispatched to the grid. These “Availability Payments” (AP) ensure guaranteed revenue streams for dam developers—including Thai construction giants and Chinese state-owned enterprises—while transferring the financial risk directly to Thai consumers.

The Cost of Idle Electrons

The financial load of this excess capacity is unclear but substantial. Costs associated with maintaining idle plants and paying for unused committed capacity are passed through to the public via the “Ft” (Fuel Adjustment) charge on monthly utility bills. In 2022 alone, EGAT accumulated a deficit of approximately 110 billion baht ($3. 2 billion), a figure exacerbated by rising global fuel prices but structurally underpinned by the obligation to service long-term PPAs. even with the existing surplus, Thai regulators continued to approve new imports. In 2023, authorities greenlit the purchase of power from the Pak Lay (770 MW) and Luang Prabang (1, 460 MW) dams, locking the country into decades-long commitments for energy it currently does not need.

The table details the between Thailand’s operational requirements and its contractual obligations, highlighting the widening gap between supply and actual consumption.

| Year | Installed Capacity (MW) | Peak Demand (MW) | Reserve Margin (%) | Key PPA Developments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 45, 480 | 28, 636 | 58. 8% | Xayaburi Dam full commercial operations commence. |

| 2021 | 46, 600 | 30, 135 | 54. 6% | Nam Theun 1 PPA active; surplus remains>50%. |

| 2022 | 49, 150 | 32, 250 | 34. 4% | Luang Prabang PPA signed (Nov); EGAT debt spikes. |

| 2023 | 49, 600 | 34, 827 | 42. 4% | Pak Lay PPA signed (Mar); Pak Beng PPA signed (Sep). |

| 2024 | 51, 200* | 36, 100* | ~41. 8% | Draft PDP 2024 10, 500 MW total imports from Laos. |

| *Provisional figures based on PDP 2024 projections and Q1 data. Reserve margin calculation includes committed imports. | ||||

Strategic Lock-in vs. Market Reality

The rationale for these agreements frequently cites “energy security” and the goal of positioning Thailand as the “Battery of Southeast Asia” via re-exporting power. Yet, the mechanics of the PPAs reveal a different priority. The tariff rates for new projects like Pak Beng are set at approximately 2. 71 baht per kilowatt-hour (kWh) for 29 years. While this appears competitive against volatile LNG prices, it locks the grid into a fixed-cost model that ignores the plummeting costs of domestic solar and renewable alternatives. By 2025, Thailand’s committed import capacity from Laos is projected to exceed 10, 500 MW, outsourcing its baseload generation to a foreign jurisdiction where environmental safeguards are minimal and hydrological data is controlled by upstream Chinese dam operators.

This arrangement creates a perverse incentive structure. EGAT, acting as a single buyer, has little financial motivation to curb over-procurement because the “pass-through” method allows it to recover costs from consumers. Consequently, the Mekong’s flow is commodified not based on actual demand, but on the financial architecture of cross-border infrastructure deals. The river is dammed to generate electricity that Thailand does not need, to pay for loans on construction projects that benefit a closed circle of developers, while the ecological cost is borne by the river system and the financial cost by the Thai public.

Nuozhadu Dam: Case Study in Flow Restriction

The Nuozhadu Hydropower Station stands as the central engine of Beijing’s upstream control over the Mekong River. Located in Pu’er City, Yunnan Province, this earth-fill embankment dam is not an energy generator. It functions as a massive hydrological tap with the capacity to sever the river’s lower arteries. The structure rises 261. 5 meters above the riverbed. It impounds a reservoir with a normal storage capacity of 21. 7 billion cubic meters (BCM). This volume is equivalent to the entire annual flow of smaller transboundary rivers. Nuozhadu operates in tandem with the Xiaowan Dam upstream. Together they command over 50 percent of the sediment and water flow that historically reached the Golden Triangle.

Operational data from 2019 through 2024 reveals a pattern of flow restriction that correlates directly with downstream instability. The dam’s primary function is to generate 5, 850 megawatts of electricity. Its secondary function appears to be the regulation of the Mekong’s pulse to suit China’s domestic needs. Engineers fill the massive reservoir during the wet season. This action withholds important floodwaters needed downstream to fertilize the Mekong Delta and signal fish migration. They then release this stored water during the dry season to drive turbines. This inversion of the natural flood pulse confuses ecological pattern and destroys riverbank agriculture in Thailand and Laos.

The drought of 2019 serves as the definitive case study for this weaponized hydrology. During the wet season of that year, the Lower Mekong Basin suffered its worst drought in fifty years. Farmers in Isan, Thailand, watched crops wither while the Tonle Sap Lake in Cambodia failed to reverse its flow. Beijing officials claimed the drought was due to low rainfall across the entire basin. Satellite data proved this claim false. The “Eyes on Earth” study conducted by climatologist Alan Basist used microwave signal analysis to measure surface wetness. The data showed that the Upper Mekong in China received above-average precipitation during the 2019 wet season. The river sections in Yunnan were swollen with rain. Yet the water never reached the border.

Nuozhadu and Xiaowan restricted an estimated 20. 1 billion cubic meters of water during this period. This volume represents a massive portion of the river’s total flow. The study indicates that without these upstream restrictions, water levels at Chiang Saen, Thailand, would have been approximately 63 percent higher. The dam operators prioritized filling the Nuozhadu reservoir to its operating level of 812 meters over maintaining the ecological health of the downstream basin. This decision transformed a manageable meteorological dry spell into a severe hydrological emergency for 60 million people.

The mechanics of this restriction are visible in gauge readings at the Chiang Saen monitoring station. In January 2021, the operators of the Jinghong Dam, which acts as the re-regulation weir for Nuozhadu, announced a flow reduction for “power grid maintenance.” The outflow dropped from 1, 410 cubic meters per second to 768 cubic meters per second within 48 hours. River levels in Thailand plummeted by nearly two meters. Boats were stranded. Riverbanks collapsed due to the sudden loss of hydraulic pressure. This event demonstrated that Nuozhadu and its subsidiary dams can physically lower the river level in another country within days. The notification from Beijing came only after the water had already begun to drop.

Sediment trapping at Nuozhadu further compounds the damage. The dam’s massive reservoir acts as a sediment sink. It captures approximately 85 to 90 percent of the silt and nutrients that enter it. This sediment starvation is causing the Mekong Delta in Vietnam to sink and shrink. The river water leaving Nuozhadu is clear and hungry. It the riverbed downstream as it seeks to regain its sediment load. This process undermines foundations and causes houses in Laos and Thailand to slide into the river. The clear water also triggers algae blooms that choke local fisheries.

| Time Period | Operational Action | Downstream Consequence | Verified Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wet Season 2019 | Reservoir Filling | Historic drought in Lower Basin even with high upstream rainfall. | ~20. 1 BCM withheld (combined with Xiaowan). |

| Jan 1-4, 2021 | Outflow Cut (Grid Maintenance) | Rapid water level drop at Chiang Saen. Navigation halted. | Level dropped ~2 meters in 48 hours. |

| Dry Season 2022 | Power Generation Release | Artificial flooding during dry months. Nesting birds drowned. | Water levels +1. 5m above historical average. |

| Wet Season 2023 | Flow Restriction | Delayed flood pulse. Tonle Sap reversal delayed by weeks. | Stung Treng flow 15% average. |

The strategic implication of Nuozhadu is absolute control. Beijing can induce drought or flood at can. The 2022 dry season saw the opposite problem of 2019. Nuozhadu released massive volumes of water to generate power for China’s industrial grid. This caused water levels in the Golden Triangle to rise more than 1. 5 meters above the seasonal average. Riverbank gardens cultivated by locals during the dry months were inundated. Sandbar nesting birds had their eggs washed away. The river no longer follows the seasons. It follows the production schedule of the China Huaneng Group.

Data from the Mekong Dam Monitor continues to track these anomalies. In late 2023 and early 2024, the pattern. The natural hydrological curve has been flattened. The peaks of the wet season are shaved off to fill the reservoir. The troughs of the dry season are filled in with turbine discharge. This might appear beneficial on a spreadsheet. In reality, it destroys the ecosystem services that rely on extreme variance. The fish of the Mekong evolved to migrate on the flood pulse. Without the signal of rising waters, migration stalls. Nuozhadu has rewritten the biological code of the river.

The absence of a binding water-sharing treaty allows this unilateralism to continue. The Mekong River Commission (MRC) absence enforcement power over China. Beijing shares only limited hydrological data and frequently classifies detailed operational schedules as state secrets. Downstream nations are left to guess when the drop or surge can arrive. The Nuozhadu Dam stands as a concrete testament to this power imbalance. It is a machine that converts a shared resource into a private asset. The water that flows through its turbines generates revenue for Yunnan, while the deficit downstream generates poverty for Cambodia and Vietnam.

Don Sahong: Blocking the Migration Corridors

The Don Sahong Dam represents a serious inflection point in the weaponization of the Mekong’s hydrology, functioning not as a power station but as a physical barricade across the river’s most important biological artery. Located in the Siphandone (“4, 000 Islands”) region of southern Laos, less than two kilometers upstream from the Cambodian border, the dam blocks the Hou Sahong channel. This specific channel is unique geologically; it is the only pathway within the Khone Falls fault line that remains passable for migratory fish year-round. By sealing this corridor, the infrastructure severs the lower Mekong’s reproductive pattern.

Construction on the 260-megawatt project began in January 2016, with commercial operations commencing in January 2020. Unlike the massive reservoir-style dams upstream in China, Don Sahong is a run-of-river project, yet its strategic placement maximizes ecological disruption. The developers, Don Sahong Power Company (a joint venture primarily led by Malaysia’s Mega Corporation Berhad), implemented engineering modifications to adjacent channels—Hou Sadam and Hou Xang Peuak—claiming these would serve as alternative migration routes. yet, independent monitoring data contradicts these assurances.

Fisheries Collapse and Economic

The operational timeline of Don Sahong correlates directly with measurable declines in downstream biomass. The Mekong River Commission’s Joint Environmental Monitoring (JEM) pilot project, released in 2022, utilized acoustic tagging to track fish movement. The data revealed that while fish were attracted to the high flow of the blocked Hou Sahong channel, they failed to locate the entrances to the modified alternative passages. Most tagged subjects eventually drifted back downstream, unable to complete their upstream migration to spawning grounds.

This biological blockade has translated into immediate economic losses for Cambodia, which relies on the Mekong for heavily on protein intake. Verified catch data from the Cambodian Fisheries Administration indicates a sharp downward trend coinciding with the dam’s commissioning:

| Year | Total Freshwater Catch (Tons) | Year-over-Year Change | Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 478, 850 | — | Pre-commissioning baseline |

| 2020 | 413, 200 | -13. 7% | Don Sahong begins commercial operations |

| 2021 | 383, 050 | -7. 3% | Full operational year |

| 2022 (Jan-May) | 93, 650 | N/A | Continued low yields reported |

At the micro-level, the impact is even more pronounced. In villages immediately downstream in Stung Treng province, monthly catch volumes per fisherman plummeted from 114 kilograms in 2018 to just 83 kilograms in 2020. This 27% reduction forces subsistence communities to purchase food they once harvested freely, directly eroding household solvency in one of the region’s poorest provinces.

Extinction of the Irrawaddy Dolphin

The dam’s proximity to the transboundary dolphin pool has decimated the local population of serious endangered Irrawaddy dolphins. The blasting and excavation required to widen the channel for turbines created lethal acoustic trauma and sediment plumes during the construction phase (2016–2019). The sub-population residing in the pool directly the dam site collapsed from five individuals in 2015 to a single survivor by 2021. This group is functionally extinct.

While the total Mekong dolphin population showed a fragile stabilization around 90 to 104 individuals between 2022 and 2024 due to crackdown on illegal gillnets, the genetic diversity represented by the upstream pod is irretrievably lost. The Don Sahong project demonstrates the high lethality of infrastructure built without regard for specific biological hotspots. An expansion project completed in 2024 added a fifth turbine, increasing capacity to 325 megawatts and further intensifying the hydrological pressure on this fragile ecosystem.

“The channel on which the dam is constructed, the Hou Sahong, is a year-round migration route for over 100 species of fish. There has been no assessment of the dam’s transboundary impacts on fisheries, even with the fact that fish are an essential source of food for 60 million people.” — EarthRights International, verified report summary.

The failure of the “engineered fish passages” at Don Sahong serves as a case study in the limitations of mitigation technology. The biological reality is that Mekong fish species, evolved over millennia to navigate specific flow cues, do not adapt to artificial bypasses at the speed required for survival. The result is a permanent reduction in the river’s carrying capacity, transforming a renewable food system into a static energy asset.

Agricultural Economics: Crop Loss Valuation in the Lower Basin

The economic devastation wrought by the weaponization of the Mekong River is measurable in billions of dollars. As upstream dams regulate flow and climate anomalies intensify, the Lower Mekong Basin has transitioned from a region of reliable seasonal abundance to one of financial volatility. Between 2015 and 2025, the four downstream nations—Vietnam, Thailand, Cambodia, and Laos—incurred cumulative agricultural losses exceeding $5 billion. These figures represent not just harvests but a structural destabilization of the region’s primary economic engine.