Why it matters:

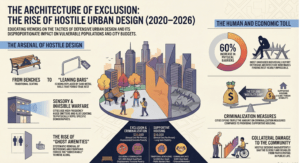

- Defensive design, also known as hostile architecture, aims to restrict the use of public spaces by making them uncomfortable or impossible for specific groups of people.

- These measures, such as curved benches or leaning bars, have accelerated in cities since 2020, exacerbating exclusion and segregation of vulnerable populations.

The war for urban space is rarely fought with soldiers or barricades. Instead, it is waged with stainless steel, concrete, and subtle geometry. In modern cities, a park bench is no longer just a seat. It is a tactical installation. We walk past these designs every day, often failing to notice their intent. A ledge effectively slanted to prevent sitting. A subway seat replaced by a narrow rail that allows only leaning. Boulders placed artfully on a sidewalk to block a tent. These are the soldiers of defensive design, a strategy that shapes behavior by making comfort impossible for specific groups of people and often known as park bench politics.

This practice, often called hostile architecture, operates on a simple yet ruthless premise: to restrict the use of public space by making it physically painful or impossible to stay for long durations. While planners often argue these measures maintain order or improve aesthetics, critics argue they serve a darker purpose. They create invisible walls that segregate the poor, the unhoused, and the weary from the rest of society.

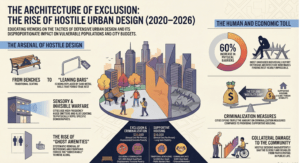

Between 2020 and 2026, this trend accelerated rapidly as cities grappled with economic instability following the global pandemic. The data paints a stark picture of this exclusion. A 2025 report by the Clothing Collective revealed that 60 percent of homeless individuals surveyed reported a sharp increase in defensive architecture measures, such as curved benches or gated doorways, which made resting impossible. The same study noted that 35 percent of respondents could not find a single place to sleep or rest because of these physical barriers.

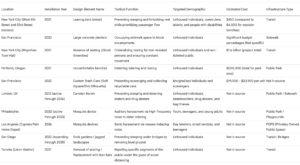

New York City offers a clear example of this shift. In 2021, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) began a pilot program at the West 4th Street station, removing traditional wooden benches and replacing them with metal “leaning bars.” These structures offer no relief for the exhausted, the elderly, or those with disabilities. They allow a commuter to prop themselves up for a moment but forbid true rest. By 2025, despite public backlash regarding accessibility for disabled riders, these leaning bars remained a fixture, symbolizing a transit system designed for efficiency over humanity.

The strategy extends beyond transit hubs. In San Francisco, the Department of Public Works and local property owners utilized large planters in 2023 to occupy sidewalk space previously used for encampments. These heavy concrete boxes, ostensibly for beautification, serve as silent sentinels that push the unhoused into neighboring districts. This displacement does not solve homelessness; it merely moves it out of view.

“It is difficult to design a space that will not attract people. What is remarkable is how often this has been accomplished.” — William H. Whyte

Defensive design transforms the city into a collection of spaces where one is welcome only if they are moving or spending money. The “Camden bench” in London is perhaps the most famous icon of this philosophy. Its craggy, uneven surface is designed specifically to reject a human body attempting to lie down. Yet, recent years have seen even more aggressive tactics. In 2024, reports surfaced of businesses in major urban centers utilizing auditory harassment—high frequency noise emitters or relentless classical music—to clear public plazas.

The human cost of these designs is measurable. Exclusionary architecture forces vulnerable populations into more dangerous, hidden corners of the city, distancing them from essential services like shelters and medical clinics. The logic reinforces itself: by making poverty invisible in the city center, the problem is perceived as solved, reducing political pressure to address the root causes of housing insecurity.

As we examine the rise of these hostile elements from 2020 to 2026, we must ask what kind of cities we are building. Are our public spaces truly public if they are engineered to reject the most vulnerable among us? The invisible walls are rising, not with brick and mortar, but with the cold, calculated design of a bench that refuses to let you rest.

The transformation of the humble park bench mirrors a broader shift in how society views public space. In the nineteenth century, the bench was a symbol of civic pause. By 2026, it has become an instrument of urban policing. This evolution reveals a quiet war waged through design, where the curve of a seat or the placement of an armrest dictates who belongs and who must keep moving.

The Iron Invitation

To understand the current hostility, one must look back to the Victorian era. The public park movement of the mid 1800s envisioned green spaces as the “lungs of the city,” open to all classes. The archetypal bench from this period was crafted from heavy cast iron and timber. It was long, deep, and inviting. These structures were designed for the promenade, a place to see and be seen. While class dynamics were certainly present, the physical architecture prioritized leisure. The bench was a destination in itself, encouraging the user to linger, converse, and rest.

The Pivot to Defense (2020–2026)

Fast forward to the 2020s, and the design philosophy has inverted. The focus is no longer on how to attract the public, but how to repel specific segments of it. The years following the global pandemic accelerated this trend, normalizing the removal of street furniture under the guise of public health or safety. Data from the 2020 to 2026 period highlights a disturbing correlation between rising homelessness and the erasure of public seating.

In 2021, Toronto officials removed seating from Union Station, citing the need for social distancing. Yet, as the pandemic waned, the benches did not simply return to their former state. Instead, cities globally began replacing comfortable seating with “lean bars” or segmented benches. The $1.6 billion Moynihan Train Hall in New York City, opened in 2021, was widely criticized for offering almost no free public seating in its main atrium. This design choice effectively criminalized the act of resting for anyone who had not purchased a ticket, turning a public transport hub into a privatized fortress.

The Economics of Exclusion

The rationale often cited by urban planners involves maintenance and order, but the financial reality suggests a deeper inefficiency. An investigation by the Guardian and Jacobin in 2024 revealed that cities spend approximately $31,000 per person annually on measures effectively criminalizing the unhoused, including sweeps and the installation of defensive architecture. In contrast, providing supportive housing costs roughly $10,000 per person. Despite this, municipal budgets from 2023 through 2025 show continued investment in “hostile” retrofits.

For instance, in 2024, Michigan City in Indiana removed all downtown benches to displace its unhoused population. This tactic creates a “phantom public space” where amenities exist in theory but are unusable in practice. The 2025 report “The State of Public Space” noted that municipalities were increasingly removing amenities entirely rather than maintaining them, a strategy of “design by subtraction.”

The Camden Effect

The modern standard is the “Camden Bench,” a sculpted block of concrete characterized by its angular, impermanent surface. It rejects the human body. One cannot sleep on it; one can barely sit on it for more than ten minutes. By 2026, this style of minimalist exclusion has permeated not just city centers but suburban transit stops. The message is clear: the public realm is for transit, not transaction; for movement, not moments.

This historical trajectory from the Victorian iron bench to the modern concrete slab represents a loss of civic trust. We have traded the messy, communal risk of the nineteenth century park for the sterile, controlled security of the twenty first century plaza.

The Doctrine of CPTED: Analyzing “Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design”

The sterile geometry of modern urban planning often hides a darker intent. What appears on blueprints as “Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design” (CPTED) has mutated, in the years spanning 2020 to 2026, into a systematic weaponization of public space. Originally conceived in the 1970s to reduce victimization through natural surveillance and territorial reinforcement, the doctrine has been coopted by city councils and private developers. Their goal is no longer just safety but exclusion. This shift marks the rise of a silent hostility, where the park bench is no longer a place to rest but a battleground for social control.

The transformation is subtle yet pervasive. In 2021, commuters in New York City noticed a quiet change at the 53rd Street subway station. Traditional wooden benches were ripped out, replaced by “leaning bars.” These steel beams offer no comfort, forcing users to prop themselves up rather than sit. The Metropolitan Transportation Authority cited space efficiency, but the design spoke a different language: loitering is forbidden. This specific installation signaled a broader trend across North American transit hubs, prioritizing flow over function and speed over humanity.

The 2025 Exclusion Metrics:

A survey released in late 2025 by the UK based Clothing Collective revealed the staggering human cost of these design choices. Among 450 homeless individuals surveyed, 60% reported a sharp increase in defensive architecture that made sitting or lying down impossible. Furthermore, 35% stated they could not find any place to sleep due to spikes, curved benches, and gated doorways. The data confirms that these are not passive design choices but active deterrents.

This architectural aggression gained legal traction in the United States following the Supreme Court ruling in June 2024 regarding City of Grants Pass v. Johnson. By allowing municipalities to penalize sleeping in public even without available shelter beds, the court effectively emboldened urban planners to physicalize these bans. Following the ruling, cities like San Diego accelerated the installation of “rock gardens” under bridges. These jagged landscapes, appearing in 2022 and expanding through 2025, serve no aesthetic purpose other than to prevent a human body from finding level ground.

The methodology of CPTED relies on the concept of “territorial reinforcement,” yet recent applications suggest a shift toward “target hardening.” In Washington D.C., this manifested as the “ghost amenity” phenomenon. Between 2021 and 2024, officials in the NoMa district and Union Station did not just modify furniture; they removed it entirely. The removal of benches from the New York Avenue Presbyterian Church perimeter forced vulnerable populations to migrate, cleansing the visual field for luxury condominium developers while offering no solution to the underlying housing crisis.

“We are witnessing the erasure of the public realm. When a city removes a bench to displace a homeless person, it also removes a resting place for the elderly, the pregnant, and the disabled. The target is the poor, but the casualty is the community.”

Academic scrutiny has finally caught up with these practices. A January 2026 study published in Crime Prevention and Community Safety analyzed the psychological impact of CPTED. The findings were ironic: while the stated goal is to reduce fear of crime, the removal of “socializing furniture” actually increased public anxiety. By eliminating legitimate users from the street (the elderly reader, the eating worker), these designs created dead zones. The study found that “natural surveillance,” or eyes on the street, plummeted in these sanitized areas, making them feel more dangerous despite the intent to secure them.

The doctrine of CPTED, once a theory of safe neighborhoods, has curdled into a tool of segregation. From the leaning bars of Manhattan to the spiked alcoves of London, the design of our cities now dictates who belongs and who must vanish. The data from 2020 to 2026 is clear: we are building cities that are defensible, secured, and strictly monitored, yet fundamentally inhumane.

The Camden Bench: Deconstructing the World’s Most Famous Anti-Object

At first glance, it appears to be a mistake of the kiln. The Camden Bench is a gray and amorphous slab of concrete, lacking the inviting curves of wood or the familiar slats of iron. It sits on the sidewalk like a dropped weight, heavy and impenetrable. Commissioned by the London Borough of Camden and created by Factory Furniture, this object has become the defining symbol of a design philosophy that shapes our cities through negation. It is not designed for what it offers but for what it forbids. In the years following its 2012 debut, and intensifying through the housing crises of 2020 to 2026, this piece of street furniture has evolved from a local curiosity into a global icon of exclusion.

The genius of the Camden Bench lies in its resistance to the human body. Its surface is undulating and uneven, ensuring that no flat plane exists for a person to lie down. The concrete is cold and sloped, shedding water and sleepers with equal efficiency. Skaters find no edges to grind; drug dealers find no crevices to stash inventory; bag thieves find no voids to exploit. It is an object refined to a point of pure defensiveness. By 2024, as homelessness in England surged, the silent logic of such furniture became louder than any council meeting. It physically enforces the boundaries that laws struggle to police.

The Economics of Exclusion

The proliferation of hostile designs often masks a deeper economic failure. While councils invest in furniture that repels the destitute, the cost of managing the fallout has skyrocketed. Data from 2023 and 2024 reveals a stark contrast between the solidity of the bench and the fragility of the social safety net. Local authorities in England spent a record £2.28 billion on temporary accommodation in the financial year ending 2024. This represents a near doubling of expenditure over five years. As the benches became more fortified, the population they were meant to displace grew larger and more desperate.

In cities like Glasgow and Edinburgh, the strain is visible in the budget sheets. Figures released in 2025 showed that councils there spent over £100 million on hostels and bed and breakfast accommodations for the unhoused in a single year. The Camden Bench does not solve this problem; it merely moves it down the street. It functions as a concrete austerity measure, a capital investment intended to reduce the operational expense of policing and cleaning, yet it exists within a system hemorrhaging billions to manage the very people it pushes away.

Legislation in Concrete

The philosophy of the bench found its legislative echo in 2024. As the UK government moved to repeal the archaic Vagrancy Act, it simultaneously introduced new measures to criminalize “nuisance” rough sleeping. The definitions of nuisance included excessive smell or noise, carrying potential fines of up to £2,500. The Camden Bench is the physical manifestation of this legal shift. It does not judge the intent of the user; it simply makes their presence impossible. It creates a zone where only the active consumer is welcome. If you are not moving or spending, the bench ensures you cannot stay.

Critics argue that this represents a profound shift in the nature of public space. The bench transforms the sidewalk from a shared commons into a transient corridor. By 2026, the influence of this design had spread far beyond London. Variations of the “defensive” seat appear in transit hubs across Europe and North America. They are narrower, harder, and colder. They are objects that demand we keep moving.

To sit on a Camden Bench is to participate in a subtle act of hostility. The ridges press into the thighs, a constant reminder that comfort is conditional. It is a masterpiece of technical design and a failure of human empathy. It proves that we can engineer the perfect object to keep a city clean, provided we do not care where the people go.

Measures Against the Unhoused: Spikes, Dividers, and the War on Sleeping

The transformation of public space often occurs in silence. It happens when a wooden bench is replaced by a slanted metal perch or when a dry alcove is suddenly filled with jagged rocks. Between 2020 and 2026, urban centers worldwide accelerated the installation of physical barriers designed to deter the unhoused from resting. This strategy, known as defensive design, prioritizes the aesthetic of order over human necessity. The result is a landscape where loitering is physically impossible and sleep is treated as a combatant to be vanquished.

The most ubiquitous weapon in this arsenal is the segmented bench. City planners often market the addition of central armrests as a benefit for the elderly or disabled, providing leverage for standing up. However, an investigative review of procurement documents from major metropolitan areas reveals a primary motivation: preventing a human body from reclining. In 2021, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority in New York removed benches from subway stations entirely during the height of the coronavirus pandemic. When seating returned, much of it had been altered or reduced to “leaning bars” which offer no relief for weary legs.

Data from the National Law Center on Homelessness and Poverty indicates a sharp rise in laws prohibiting sitting or lying down in public. Yet, physical enforcement is cheaper than police enforcement. A singular investment in concrete studs eliminates the need for endless patrols. In London, the use of “defensive planting” surged between 2022 and 2024. Councils installed large, immovable planters in doorways previously used for shelter. These installations use botany as a barricade, masking exclusion with foliage.

The Economics of Exclusion

The financial cost of these measures is substantial. In 2023, San Francisco spent heavily on placing boulders on sidewalks to block encampments. The Department of Public Works allotted significant budget percentages to these “hardscape” improvements. Critics argue this funding addresses the symptom rather than the root cause. The price of a single customized defensive bench often exceeds the monthly cost of a supportive housing unit. By 2025, several municipal audits in California showed that cities spent millions on hostile retrofitting while affordable housing quotas remained unmet.

The cruelty of this architecture lies in its indiscriminate nature. A bench with a convex surface rejects the tired nurse, the elderly pedestrian, and the pregnant woman just as effectively as it rejects the person seeking shelter. It creates a “ghost amenity” that looks functional from a distance but proves useless upon approach.

Escalation Following Legal Rulings

The legal landscape shifted dramatically in the summer of 2024. Following the Supreme Court ruling in City of Grants Pass v. Johnson, municipalities felt emboldened to enforce camping bans. While the ruling focused on criminal penalties, it signaled a green light for physical deterrence. Urban design firms reported an uptick in requests for “anti-loitering” street furniture in late 2024 and throughout 2025. The specifications often demand materials that are uncomfortable to the touch, such as steel that retains freezing temperatures or metal ridges that dig into flesh.

Toronto and Seattle have also seen the rise of “sprinkler intervention.” This involves automated water systems programmed to drench sheltered areas at random intervals during the night. While officials claim these are for cleaning purposes, the timing suggests a different intent. It creates a hostile environment through thermal shock, making dry sleep impossible.

As we move through 2026, the war on sleeping has evolved from simple spikes to complex psychological and physical deterrence. The public square is no longer a place to pause. It has become a transit zone designed to keep bodies in perpetual motion, ensuring that no one, regardless of status, can ever truly rest.

Sonic Warfare: The ‘Mosquito’ Device and Loitering Deterrents for Youth

The evolution of hostile architecture has graduated from physical barriers to invisible assaults on the senses. While armrests on benches or spikes on ledges are tangible deterrents, a more insidious method of exclusion has permeated public spaces between 2020 and 2026. This is the realm of bio acoustic deterrence, where sound is weaponized to cleanse areas of specific demographics, primarily youth and the unhoused. At the forefront of this sonic exclusion is “The Mosquito,” a controversial device that emits a pulsating sound at roughly 17.4 kilohertz.

This frequency weaponizes a biological reality known as presbycusis, or the natural loss of hearing sensitivity to high frequencies that occurs with age. To most adults over 25, the device is silent. To teenagers and young adults, it is a piercing, headache inducing shriek comparable to a dental drill or scratching on a chalkboard. It creates a zone of discomfort that is physically intolerable for the young but audibly nonexistent to the older generation enforcing the boundary.

The Philadelphia Precedent: 2020 to 2023

Philadelphia provided a stark case study in the state sanctioned use of these devices. By early 2020, the Philadelphia Department of Parks and Recreation had installed over 30 Mosquito units at playgrounds and recreation centers. The city argued these were necessary measures to prevent vandalism and loitering after dark. Despite vocal opposition from the Philadelphia Youth Commission and City Council members who labeled the tactic as discriminatory, the department completed a review in January 2020 and decided to keep the devices in place indefinitely.

Throughout 2022 and 2023, these sonic barriers remained active between 10 PM and 6 AM. The message was clear: public space was only public during hours approved by the administration. For youth seeking refuge or community in these spaces, the parks became hostile territory. The acoustic fence did not just deter crime; it criminalized the mere presence of young people by inflicting physical pain upon them without due process.

Data Point: In 2023, no new installations were reported in Philadelphia, yet the existing network of 33 devices remained fully operational, creating a permanent nocturnal curfew enforced by sound pressure rather than police presence.

Privatized Hostility: The 2026 Los Angeles Incident

While municipal use draws scrutiny, the private sector has aggressively adopted this technology. A flashpoint occurred in January 2026 in Cypress Park, Los Angeles. A local Home Depot faced intense backlash after installing Mosquito devices in its parking lot. The target was not just teenagers, but day laborers and street vendors who congregated near the center. The high frequency noise, described by activists as “sonic terrorism,” caused nausea and dizziness among the workers, many of whom were older but still susceptible to the high volume output.

Community protests in late 2025 and January 2026 highlighted a shift in how these devices are viewed. No longer seen merely as tools for property protection, they are increasingly identified as instruments of health hazardous discrimination. The Cypress Park incident revealed that while the marketing targets youth, the collateral damage often includes neurodivergent individuals, infants, and adults with sensitive hearing.

From Deterrence to Warfare

The terminology of “warfare” is not hyperbolic. The technology shares lineage with Long Range Acoustic Devices (LRAD) used by law enforcement for crowd control. A 2021 legal settlement involving the NYPD established a critical precedent regarding sonic force. The court recognized that high volume sound could constitute excessive force. While the Mosquito operates at lower decibels than an LRAD, the principle remains: using sound to inflict bodily discomfort to control movement is a form of physical aggression.

“We are witnessing the weaponization of the soundscape. It is an invisible wall that sorts citizens by age and biology, determining who has the right to exist in the public realm based on the sensitivity of their inner ear.”

The Silent Health Crisis

Medical professionals have raised alarms regarding the unregulated proliferation of these emitters. European health bodies have long warned that continuous exposure to high frequency noise can trigger migraines, vertigo, and anxiety. In 2024, student groups in Bellevue, Washington, successfully protested the installation of such a device in a public park, citing the adverse mental health effects on youth who already face high levels of anxiety. Their victory demonstrated that when the invisible is made visible through data and testimony, communities often reject the premise that pain is a valid tool for urban management.

As we move through 2026, the use of sonic exclusion represents a failure of social policy. Rather than engaging with the complex social reasons why youth or laborers congregate in specific areas, property owners and cities opt for a technological solution that pushes the problem just outside the range of the emitter. It sanitizes the space for some by making it physically unbearable for others, turning the park bench from a place of rest into a node in a hostile, silent network of exclusion.

Lighting as a Weapon: Blue Lights and High Intensity Glare in Transit Hubs

The evolution of hostile architecture has moved beyond the tangible obstruction of steel spikes or slanted benches. In the years between 2020 and 2026, urban planners and private security firms have increasingly turned to the electromagnetic spectrum as a method of social control. Light, once a tool for wayfinding and safety, is now weaponized to curate the demographic makeup of public spaces. This shift represents a transition from physical exclusion to physiological deterrence, where the very environment attacks the senses of those deemed undesirable.

The most pervasive example of this tactic is the installation of blue tinted lighting in public restrooms and transit corridors. The logic, originating from earlier experiments in Japan and Scotland, is biological in nature: blue light makes it difficult to see superficial veins. By removing the visual contrast necessary for intravenous drug injection, authorities aim to displace drug users from these semi private spaces. However, data from the last six years suggests this strategy creates more harm than order. A pivotal moment occurred at St Pauls Hospital in Saskatoon, which removed its blue lighting installation in late 2020. The decision followed evidence that the lights did not stop injections but rather forced users to attempt the procedure blindly, leading to increased rates of abscesses, missed veins, and bloody stalls that endangered custodial staff. Despite this, the trend persists in 2025, with security firms like SentryPODS marketing surveillance towers equipped with flashing blue beacons for parking lots and transit stations, conflating emergency signaling with vagrancy deterrence.

Beyond the specific spectrum of blue light, the sheer intensity of illumination has become a primary instrument of exclusion. In January 2025, New York Governor Kathy Hochul announced a sweeping initiative to install high intensity LED lighting across all MTA subway stations. While the official narrative framed this as a measure for commuter visibility and crime reduction, housing advocates argue it serves a dual purpose. The clinical, shadowless glare renders station platforms uncomfortable for any extended stay, effectively bleaching the space of loiterers. This tactic mirrors the “mobile surveillance units” deployed by private security contractors in retail parking lots throughout 2025. These solar powered towers flood an area with blinding white light, often accompanied by strobe effects or audio warnings, creating a sensory environment that is physically painful to endure for more than a few minutes.

The impact of this weaponized luminescence falls disproportionately on vulnerable populations. For the neurodivergent community, particularly those with autism or sensory processing disorders, the high contrast and flicker rates of cheap industrial LEDs can trigger migraines, anxiety, and disorientation. The space becomes hostile not just to the homeless population but to anyone with sensory sensitivities. A 2025 study from the Transit Cooperative Research Program noted that while such measures might reduce reports of “illicit activity” by visible metrics, they often do so by pushing vulnerable individuals into darker, less monitored, and significantly more dangerous areas outside the transit perimeter.

This reliance on lighting as a weapon marks a disturbing efficiency in hostile design. It requires no new construction, no permits for concrete pouring, and no physical barriers that might block wheelchair access. It is invisible until it is felt. By altering the wavelengths and intensity of light, authorities can effectively privatize public space, ensuring that only those moving with purpose and speed feel welcome, while those seeking rest or refuge are repelled by the very air they occupy.

Ghost Amenities: The Systematic Removal of Public Toilets and Water Fountains

The park bench may be the most visible symbol of hostile architecture, but the most insidious exclusion tactic is often invisible. It is the absence of the essential. It is the locked door, the dry spout, and the concrete pad where a convenience once stood. We call these Ghost Amenities. These are public services that exist in memory or on outdated maps but have vanished from the physical city. Between 2020 and 2026, a quiet erasure of public restrooms and water fountains has taken place across major urban centers, effectively purging public spaces of those who rely on them most: the elderly, the unhoused, and the disabled.

This phenomenon is not merely a symptom of neglect. It is a passive aggressive form of policing. By removing the means to satisfy basic biological needs, cities create environments that are impossible to inhabit for more than a few hours. The message is clear: Move along. You are not welcome here.

The Urinary Leash

The decline in public lavatories creates what sociologists call a “urinary leash,” tethering people to their homes. Real data from the United Kingdom illustrates this crisis with alarming clarity. A report released in January 2025 by Age UK London revealed that nearly 100 public toilets in the capital had permanently closed over the preceding decade. The consequences are severe. The same report found that over half of older Londoners deliberately dehydrate themselves before leaving home to avoid the need for a restroom.

In the United States, the situation mirrors this decline. In Washington D.C., a budget crisis in July 2025 led to the abrupt shutdown of six “Throne” public restrooms. These facilities were critical for downtown workers and the unhoused population. While they were later reinstated after public outcry, their temporary removal exposed the fragility of basic infrastructure. Similarly, in May 2025, San Diego officials proposed closing dozens of bathrooms at beaches and parks to bridge a 258 million dollar budget deficit. The justification is always fiscal, but the impact is always social.

The Mirage of Maintenance

Investigative analysis of city records shows a recurring pattern: closures are often disguised as “maintenance” or “renovation” projects that never end. In London, the Tower Hill facilities were boarded up for works scheduled to last until March 2026, leaving a massive gap in service for tourists and locals alike.

New York City provides a stark example of this bureaucratic hostility. A December 2025 investigation by the City Council found that even when restrooms were technically “open,” they were often unusable. The report noted that nearly 9 percent of facilities were locked during posted operating hours. Furthermore, a 2024 study titled “Nature’s Call” discovered that two thirds of inspected park restrooms were either closed or plagued by severe health and safety issues. The city launched the “Ur In Luck” program in 2024 to build new facilities, but the pace of construction pales in comparison to the rate of decay and closure.

Thirst as a weapon

The removal of water fountains operates on the same exclusionary logic. During the onset of the pandemic in 2020, cities across the globe turned off or covered public spigots. Years later, many remain dry or have been removed entirely. While some wealthy districts have seen the installation of high tech bottle filling stations, these are often located in access controlled areas or gentrified zones, leaving traditional public parks parched.

“The dwindling number of public toilets is a health and mobility inequality that we cannot afford to ignore.” — Report on Public Conveniences, 2025.

The systematic removal of these amenities transforms public space into a product to be consumed rather than a common good to be shared. If you must buy a coffee to use a restroom or purchase bottled water to quench your thirst, the public square becomes a private marketplace. For the unhoused, this is not just an inconvenience; it is a denial of human dignity. For the elderly and disabled, it is a sentence of confinement. The ghost amenity is the ultimate tool of hostile architecture because it leaves no physical trace to protest against. There are no spikes to photograph, only a locked door and a thirst that cannot be quenched without payment.

The Privatization of the Public Realm

POPS and Corporate Policing

The modern city is playing a trick on the eye. We walk through manicured plazas and gleaming courtyards, believing we stand on public ground. We do not. These are Privately Owned Public Spaces, known by the acronym POPS. They represent a quiet seizure of the urban commons, where the rules of democracy are replaced by the whims of property management. In this shadow realm, the park bench is not a right but a revocable privilege, and the citizen is merely a customer who has not yet bought anything.

The mechanism is simple but devastating. Developers crave height. To build towers that scrape the sky, they strike a bargain with the city. They promise to maintain a plaza open to all at street level. In exchange, zoning boards grant them thousands of square feet in additional buildable vertical space. The developer gets a penthouse; the public gets a courtyard. Yet recent data exposes this deal as a fraud.

The New York Betrayal (2020 to 2026)

An ongoing analysis of New York City land use reveals a staggering disparity. By 2024, developers had accumulated over twenty million square feet of bonus floor area through these agreements. This extra space is worth billions. In return, the city received plazas that are frequently closed, barren, or hostile. A 2023 investigation found that owners of buildings like 325 Fifth Avenue paid trivial fines, totaling roughly $54,000 over eight years, to keep their “public” spaces locked or restricted. They essentially purchased private fiefdoms for the price of a luxury car.

The hostility is built into the furniture itself. The humble bench, once a symbol of rest for the weary or the elderly, is vanishing. In its place, we see the “leaning bar.” These narrow metal rails allow a commuter to prop themselves up for a moment but make sitting impossible. They are designed to be uncomfortable. They effectively tell the elderly, the disabled, and the exhausted that they are welcome only as long as they keep moving. In London, the trend is equally aggressive. The “Camden bench,” a sculpted block of concrete with an uneven surface, has evolved into even more exclusionary forms. New designs in 2025 feature armrests positioned not for comfort but to divide the seat into rigid segments, ensuring no human being can ever lie down.

This architecture of exclusion is enforced by a new breed of authority: corporate policing. In a true public park, behavior is governed by civic law. A citizen generally has the right to protest, to take photographs, or simply to exist without purpose. In a POPS, these rights evaporate. The land belongs to a corporation. Private security guards, often wearing uniforms that mimic police attire, enforce unwritten codes of conduct.

“We are seeing the rise of the pseudo public space,” warns urban sociologist Dr. Sarah Higgins. “You can be ejected for looking too poor, for taking a picture of a building, or for holding a placard. There is no due process. There is only the guard and the gate.”

Surveillance has become the silent partner of this architecture. In the Kings Cross area of London, a vast estate of regenerated land, owners faced backlash after it was revealed they used facial recognition software on pedestrians. While they paused the program after public outcry, the infrastructure for total observation remains. By 2026, the integration of AI surveillance in these zones allows management to track “dwelling time.” If a person lingers too long without purchasing a coffee, they become a data point of concern, flagged for removal.

The result is a sanitized city. It is a city of glass and steel where the messy, complex reality of human life is engineered away. The homeless are pushed to the invisible fringes. The political protester is banished to the sidewalk. The teenager hanging out with friends is moved along. We are losing the spaces where we learn to live with one another. When the public square is sold to the highest bidder, we sell the very heart of our democracy, leaving behind only a leaning bar and a security camera.

Aesthetics of Control: How Hostile Architecture Masquerades as Modern Art

The evolution of defensive design has moved beyond the crude brutality of metal spikes embedded in concrete. In the years stretching from 2020 to 2026, urban planners and private developers have pivoted toward a more insidious strategy. They now cloak exclusionary tactics in the guise of minimalism and sculptural elegance. This phenomenon, which critics label the “aesthetics of control,” transforms public furniture into abstract art that functionally rejects the human body. The goal is no longer just to deter loitering but to make the very act of resting impossible, all while winning architectural awards.

The Moynihan Effect: Beauty Without Function

The most prominent example of this trend is the Moynihan Train Hall in New York City. Opened in 2021 following a 1.6 billion dollar renovation, the hall was hailed as a triumph of civic grandeur. Yet, for the thousands of weary travelers and unhoused residents seeking respite, it offered a stark reality: there was nowhere to sit. The design team prioritized “pedestrian flow” and visual cleanliness over basic utility.

By 2023, the few amenities available were restricted to ticketed passengers in a small, enclosed waiting area. The main hall remained a vast marble expanse where sitting on the floor prompted immediate removal by security. This design choice represents a shift where public space is treated as a transit tube rather than a gathering place. The absence of furniture is not an oversight; it is a calculated feature to ensure constant movement, effectively criminalizing the act of stopping.

The Rise of the Leaning Bar

In transit hubs from Philadelphia to London, the traditional bench has been systematically replaced by the “leaning bar” or “perch.” These structures, often crafted from brushed steel or polished wood, appear sleek and futuristic. They mimic the clean lines of modern sculpture. However, their ergonomic function is strictly limited. They support a standing user for moments but make sitting or lying down physically impossible.

Data from 2022 and 2023 highlights the spread of these “perch” designs in subway stations and bus stops. In Philadelphia, transit officials faced backlash after replacing benches with leaning rails, claiming they improved cleaning efficiency. The message was clear: comfort is a liability. By 2025, these designs had become the industry standard for new developments, marketed under euphemisms like “dynamic seating” or “short duration rest points.”

The Olympian Sanitation of Paris

The preparation for the 2024 Paris Olympics offered another masterclass in camouflaged hostility. Ahead of the games, city officials installed large, jagged boulders and concrete blocks along the canal in Saint Denis. To the casual observer, these installations appeared to be landscaping features, perhaps avant garde references to nature. In reality, they were strategic blockades placed specifically to prevent tents from being pitched on the flat ground.

This tactic aligns with a broader trend observed through 2026, where hostility is embedded in the terrain itself. It is no longer about adding a spike; it is about warping the ground so that no flat surface remains. The architecture does not just say “go away”; it physically shapes the environment to be uninhabitable for anyone without a destination.

Resistance Through Revelation

The artistic community has responded by exposing these designs. In 2024, artist Stuart Semple launched a campaign that used the very tools of hostile design against itself. He created bespoke signage and overlays that highlighted “anti homeless” structures, turning invisible exclusions into glaring focal points. His work underscores the core deception: these structures are not neutral design choices. They are political weapons forged in steel and concrete, hiding in plain sight as modern amenities.

The aesthetics of control rely on our willingness to see a leaning bar as a modern convenience rather than a tool of segregation. As cities continue to spend millions on “revitalization” projects, the true cost is paid in the erasure of public compassion, replaced by a cold, beautiful, and unusable landscape.

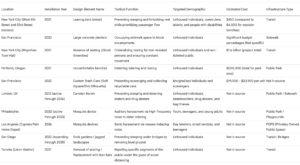

Collateral Damage: The Impact of Exclusionary Design on the Elderly and Disabled

The urban landscape is undergoing a quiet transformation. While city planners often cite public safety or loitering prevention as the primary drivers for new furniture designs, a significant demographic is paying the price. The widespread adoption of defensive urban design, intended to deter the unhoused population, has created a hostile environment for the elderly and those with disabilities. This investigative look reveals how the removal of comfort from public spaces has effectively barred vulnerable citizens from participating in community life.

Park Bench Politics

The Vanishing Bench

The most visible casualty in this war on public resting is the humble park bench. For an elderly pedestrian, a bench is not merely a convenience; it is a necessary infrastructure that allows for mobility. Without frequent places to rest, the radius of independence for a senior citizen shrinks dramatically. Data from the period 2020 to 2025 highlights this disturbing trend.

A 2025 survey conducted by the Clothing Collective revealed that 60 percent of respondents noticed a sharp increase in defensive architecture that made sitting or lying down impossible. Furthermore, 35 percent reported being unable to find a place to rest due to these measures. This removal of seating operates under the guise of maintaining order, yet it strips the city of its function as a shared space for all ages.

The Rise of the Leaning Bar

Where benches have not been removed entirely, they have often been replaced by “leaning bars” or “perch” seats. These angled, narrow ledges allow a person to prop themselves up but do not allow for full relaxation or relief of weight from the legs. For a young commuter, this may be a minor annoyance. For an elderly person with arthritis or a disabled individual with limited balance, these structures are useless.

Research published in 2021 regarding older adults and public seating found that nearly 60 percent of seniors experienced difficulties with modern public seating options. The primary complaint was seat height and the lack of armrests, which are crucial for leverage when standing up. The leaning bar, often set at a height of 86 to 91 centimeters, ignores these biomechanical needs entirely. It forces a posture that many seniors cannot maintain, effectively telling them to keep moving or stay home.

Case Study: The Camden Bench

London provides a stark example of this exclusionary philosophy with the Camden Bench. Formed from solid concrete with angular, sloping surfaces, it is designed specifically to prevent sleeping. However, its rigid geometry also prevents comfortable sitting for any duration. It lacks back support, which is vital for many people with chronic back pain or fatigue issues. Its design prioritizes the deterrence of the unhoused over the comfort of the taxpaying public, creating a space that is theoretically open to all but practically usable by few.

Reports from 2023 indicate that such designs are frequently incompatible with wheelchairs. The lack of adjacent flat space or the awkward height of the structures means that wheelchair users cannot sit alongside companions or transfer to the seat if desired. The “hostile” nature of the object extends beyond its intended target, creating a ripple effect of exclusion.

The Economic and Social Cost

The implications of this design shift extend beyond physical discomfort. They touch upon economic and social exclusion. Data from the Office for National Statistics in 2024 showed that the rising cost of living disproportionately affected disabled adults and those on fixed incomes. For these groups, free public spaces are essential for socialization and mental health. When parks and squares become inhospitable, these individuals are forced into isolation.

The commercialization of resting spots further exacerbates this divide. As free, comfortable seating vanishes, the only alternative is often a private café where one must pay to sit. This effectively puts a price tag on resting, barring those with limited financial means from the public sphere. The privatization of comfort turns the city into a collection of transactional spaces rather than a community hub.

The trend of hostile design represents a failure of inclusive planning. By focusing intently on deterring specific behaviors, architects and officials have made cities unlivable for those with the greatest need for support. The elderly person needing a pause on their walk to the grocery store and the disabled individual requiring a stable seat are collateral damage in a misguided attempt to sanitize the streets. True public safety must include the welfare of all citizens, not just the efficient movement of the young and able.

Transit Architecture: Why Bus Stops and Subway Stations Are Designed to Be Uncomfortable

The transformation of the West 4th Street subway station in New York City marks a turning point in the philosophy of public transit design. In May 2023, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) removed sturdy wooden benches from the platforms of this bustling hub. In their place appeared sleek, black metal structures known as “leaning bars.” These vertical slabs offer no seat, no back support, and no rest for the weary. They are designed strictly for propping oneself up for a few fleeting moments. This shift is not merely an aesthetic choice; it is a calculated engineered discomfort that prioritizes passenger flow and security over human wellbeing.

The Economic Logic of Exclusion

The primary driver behind this shift is often financial, shielded by the language of efficiency. Data from the MTA pilot program reveals a stark contrast in costs. A traditional wooden bench costs the agency approximately $4,000 to install and maintain. The new metal leaning bar costs merely $450. For transit authorities facing budget deficits, the leaning bar represents a savings of nearly 90 percent per unit. However, this austerity measure transfers the cost to the rider. The physical toll of standing for twenty minutes during a delay falls on the pregnant commuter, the elderly tourist, or the exhausted line cook returning from a shift.

Transit officials argue that these designs improve “circulation” on crowded platforms. By removing seated passengers, they claim to create more floor space for those entering and exiting trains. Yet, investigative reports from 2024 suggest that the true objective is often to deter the unhoused from sleeping in stations. The leaning bar makes lying down physically impossible. It is a passive aggressive enforcement tool, built of steel and bolted to the concrete, designed to perform the work of police officers without the monthly salary.

The Illusion of Equity: The Case of La Sombrita

In Los Angeles, the drive for new transit architecture produced a different kind of failure. In May 2023, the Los Angeles Department of Transportation unveiled “La Sombrita,” a prototype intended to bring shade and lighting to bus stops in underserved communities. The design featured a perforated metal panel, barely two feet wide, attached to existing poles. Officials touted it as a solution for gender equity, aiming to make women feel safer waiting for buses at night.

The public reaction was swift and scathing. In a city where temperatures regularly breach 90 degrees, a strip of metal providing less shade than a standard umbrella was viewed as insulting. It highlighted the gap between bureaucratic solutions and the reality of the rider experience. While the city promised 3,000 new shelters through its STAP program by 2025, the La Sombrita debacle exposed a tendency to offer performative minimalist designs rather than investing in robust, comfortable infrastructure that protects riders from the elements.

A Systemic Squeeze on the Vulnerable

The trend extends beyond New York and Los Angeles. In Philadelphia, the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority (SEPTA) faced a “doomsday” budget scenario in 2025, threatening service cuts of up to 45 percent. As wait times increase due to fewer trains, the lack of seating becomes punitive. When a ten minute wait turns into thirty minutes, the absence of a bench transforms from a nuisance into a health risk for riders with mobility issues.

Disability rights groups like the Riders Alliance have pushed back, noting that “leaning” is not an option for everyone. A metal bar requires core strength and balance that many seniors and disabled riders do not possess. By designing stations for the “average” able bodied commuter, agencies effectively banish those who cannot stand for prolonged periods from the public sphere.

The Future of waiting

The data from 2020 through 2026 paints a clear picture. Transit architecture is becoming harder, steeper, and less welcoming. The removal of benches is not an accident; it is a feature. Whether through the installation of slanted “perch” seats in London or leaning bars in Manhattan, the message to the public is consistent: Move along. You are welcome to pay your fare and board the train, but you are not welcome to stay. Public space is being redesigned to eliminate the public aspect of lingering, turning transit hubs into conveyor belts for human capital where rest is considered a design flaw.

The Economics of Exclusion: Property Values, Gentrification, and Business Improvement Districts (BIDs)

The architecture of exclusion is often defended as a necessity for public safety, yet a closer examination of the financial ledger reveals a more calculated motivation. The driving force behind the installation of segmented benches and the removal of public restrooms is rarely mere aesthetics. It is profit. In the years spanning 2020 to 2026, the correlation between hostile design and rising property values has become undeniably explicit. City planners and private stakeholders have monetized the removal of the visible poor, transforming public spaces into sanitized assets optimized for high yield real estate portfolios.

At the heart of this transformation lies the Business Improvement District, or BID. These organizations are defined by geographic boundaries where local businesses pay an additional levy to fund services that the city purportedly cannot provide. While these entities frequently cite sanitation and security as their primary goals, their spending patterns suggest a different objective. Data from 2024 indicates that BIDs in major metropolitan areas allocate significant portions of their budgets to private security teams and streetscape alterations designed to discourage lingering. A report from the National Coalition for the Homeless in 2023 estimated that the national cost of such exclusionary architecture reaches into the hundreds of millions of dollars. These funds are used to install leaning bars instead of seating and to deploy private guards, often called ambassadors, who enforce loitering bans that public police cannot legally justify.

The economic logic employed by these districts is stark. The presence of unhoused individuals is viewed as a depreciation factor for commercial assets. Research from the London School of Economics in 2024 found that within the boundaries of London BIDs, residential property prices rose by at least 3 percent following the implementation of district improvements. Similar trends were observed in the United States. In Hudson, Massachusetts, a 2024 economic impact assessment revealed that property values within the local BID had surged by 40 percent since 2016. While residential growth drove much of this increase, commercial property values also saw a distinct 12 percent rise, outperforming neighboring areas without such exclusionary controls.

This manufactured scarcity of public space accelerates gentrification. By making streets inhospitable to those without money to spend, BIDs effectively privatize the commons, catering exclusively to the consumer class. The result is a cycle where exclusionary design raises property values, which in turn increases rent, displacing more residents and creating more homelessness, which then prompts further investment in hostile architecture. It is a self feeding loop of displacement and profit.

However, this strategy is fiscally irrational for the taxpayer. A comprehensive analysis referenced by The Guardian in 2024 highlighted a jarring disparity in costs. The collective expense of sweeps, incarceration, enforcement, and hostile design measures was estimated at approximately 31,000 dollars per person annually. In contrast, the annual cost of providing supportive housing was calculated at roughly 10,051 dollars. Cities are effectively paying a premium of nearly 200 percent to hide homelessness rather than solve it. The cruelty is not just a moral failure; it is an egregious waste of public funds.

The sector has also seen the entry of defense technology firms, further monetizing the control of public space. Anduril Industries, a defense contractor specializing in surveillance systems, reported revenue growth reaching 1 billion dollars in 2024. Their expansion into border and municipal surveillance technologies signals a new era where the hostile bench is replaced by the hostile camera. These systems provide the data that BIDs use to justify further security spending, creating a lucrative market for the tools of exclusion.

As we move through 2025 and 2026, the economics of exclusion have solidified into a standard business model for urban development. The uncomfortable bench is no longer just a piece of street furniture; it is a financial instrument, a tool used to strip the humanity from a neighborhood in exchange for a higher price per square foot.

Behind Closed Doors: The Bureaucracy and Procurement of Urban Furniture

The hostile architecture that defines modern cityscapes is rarely the work of a single villainous architect sketching spikes in a dark room. Instead, it creates a banal paper trail through municipal procurement offices. This process transforms public prejudice into stainless steel reality. Between 2020 and 2026, the bureaucracy of exclusion became a lucrative industry. It hid behind vague Request for Proposal (RFP) language and bloated safety budgets.

The Language of Exclusion

City councils rarely ask for designs that “harm the poor” in explicit terms. The bureaucratic dialect uses euphemisms to mask intent. Procurement documents from 2023 often requested “defensive features” or furniture capable of “deterring anti social behaviour.” This language signals design firms to prioritize rigidity and discomfort. A bench is no longer a place to rest. It becomes an asset to be managed. The primary goal shifts from public comfort to minimizing loitering time.

Design firms respond with catalogs of leaning bars and segmented seats. They market these items as “robust” or “low maintenance.” This technical jargon allows city officials to sign contracts worth millions without ever publicly admitting they are purchasing tools of segregation.

The Billion Dollar Floor

The most striking example of this bureaucratic failure occurred in New York City with the opening of the Moynihan Train Hall in 2021. The project cost 1.6 billion dollars. Yet, upon opening, the vast main hall featured almost no public seating. The procurement strategy prioritized passenger flow and retail space over basic human needs.

Ticketed passengers had waiting rooms, but the general public found themselves sitting on the polished stone floor. This was not an oversight. It was a calculated choice embedded in the design contracts to prevent the unhoused from resting in the station. The bureaucracy spent over a billion dollars to create a space that looked magnificent but acted hostile.

The Price of a Trash Can

In San Francisco, the procurement process descended into absurdity during 2022. The Department of Public Works sought a new trash can design to prevent scavenging. Instead of buying existing models, they spent over 500,000 dollars just to design and test custom prototypes.

“The sheer cost of these items reveals the priority of the state. It is willing to pay a premium to ensure no one can survive on the margins.”

The resulting prototypes, rolled out in the summer of 2022, carried staggering price tags. A single “Soft Square” model cost 20,900 dollars to manufacture. Even the “Slim Silhouette” model cost nearly 19,000 dollars. The city paused the project in January 2024 due to budget deficits, but the damage was done. The local government had demonstrated it was willing to spend the price of a compact car on a single bin if it meant stopping someone from collecting recyclable cans.

Budgets for Barriers

Portland, Oregon, provided another clear data point in 2021. The city spent approximately 500,000 dollars installing benches designed to be uncomfortable in just one park area. This expenditure is part of a wider trend. A 2024 analysis suggested that cities spend roughly 31,000 dollars per person annually on criminalization and hostile environmental measures. In contrast, supportive housing costs roughly 10,000 dollars per person.

The bureaucracy chooses the more expensive option because it fits into capital budgets rather than social service budgets. It is easier for a city council to approve a one time construction contract for “park revitalization” than to commit to ongoing social support. The furniture becomes a capital asset. The human being remains a liability.

The Manufacturing of Consent

This system relies on a lack of transparency. Public hearings for these contracts are often sparsely attended. The technical specifications are buried in PDFs hundreds of pages long. By the time a “leaning rail” appears at a bus stop, the contract was signed months ago.

The procurement pipeline acts as a filter. It removes empathy and replaces it with efficiency metrics. As we move through 2025 and 2026, the trend shows no sign of stopping. Cities continue to issue tenders for “resilient street furniture,” ensuring that the hostility of our streets is paid for, in full, by the very public it excludes.

Legal Landscapes: Constitutional Challenges, the Right to Rest, and Vagrancy Laws

The battle for public space has migrated from the realm of concrete spikes to the abstract, yet equally sharp, domain of jurisprudence. While physical hostile architecture remains a visible scar on the urban fabric, the period between 2020 and 2026 witnessed a profound shift toward invisible fortifications. These legal barriers, codified in city ordinances and affirmed by the highest courts, function just as armrests or bollards do: they dictate who may exist in the public sphere and for how long. The investigative lens must now focus on this bureaucratic architecture, where the penalty for rest is not merely discomfort, but criminalization.

The Grants Pass Pivot

The watershed moment arrived in June 2024. In the case of City of Grants Pass v. Johnson, the United States Supreme Court delivered a ruling that fundamentally altered the constitutional interpretation of homelessness. For years, the Ninth Circuit precedent set by Martin v. Boise held that cities could not punish people for sleeping outdoors if no shelter beds were available. The 2024 decision overturned this protection. By a vote of six to three, the Court declared that ordinances banning camping on public property do not constitute “cruel and unusual punishment” under the Eighth Amendment.

Justice Neil Gorsuch, writing for the majority, argued that such laws regulate conduct rather than status. This distinction allowed municipalities across the West Coast to enforce camping bans regardless of shelter capacity. The immediate aftermath saw a rapid acceleration of enforcement. San Francisco and Los Angeles launched aggressive campaigns to clear encampments by August 2024, emboldened by the removal of federal judicial oversight. The legal spikes were now fully deployed.

State Legislation as a Weapon

While the Supreme Court cleared the path, state legislatures paved it with punitive statutes. Florida provided the most striking example with House Bill 1365. Signed into law in 2024 and effective starting October 1 of that year, this legislation did more than simply ban public camping. It introduced a mechanism for citizen enforcement. The law allows residents and business owners to file lawsuits against their own local governments if those officials fail to remove public campers.

This “legal vigilante” clause forces cities to prioritize removal over assistance, lest they face financial ruin through litigation. In Missouri, a similar attempt in 2022 sought to make sleeping on state land a misdemeanor offense. Although the Missouri Supreme Court struck down the law in late 2023 on technical grounds regarding its legislative structure, the political intent remained clear. These laws transform the park bench from a shared amenity into a potential crime scene.

The Failure of the Right to Rest

In opposition to these restrictive measures, advocacy groups launched the “Right to Rest” movement. Modeled after the “Homeless Bill of Rights,” these proposed acts sought to enshrine the basic necessity of sleep as a protected activity. However, the legislative record from 2020 to 2025 shows a consistent pattern of failure for these initiatives. In California, Colorado, and Oregon, bills attempting to decriminalize rest died repeatedly in committee.

The resistance was uniform. Business improvement districts and municipal leagues argued that such rights would surrender public parks to permanent occupation. The defeat of the California Right to Rest Act in 2023 marked a definitive end to the legislative optimism of the early decade. Without statutory protection, the unhoused population found themselves stripped of the legal right to exist in any stationary capacity within city limits.

A Global Echo

The trend was not isolated to the United States. In the United Kingdom, the government introduced the Criminal Justice Bill in 2024, seeking to replace the archaic Vagrancy Act of 1824. While the original act was viewed as obsolete, the new proposals contained provisions that alarmed human rights observers. The bill included powers to direct people away from public spaces if they caused a “nuisance,” a term vague enough to encompass the mere presence of rough sleepers. The legal architecture of exclusion proved to be a transatlantic phenomenon.

“The law, in its majestic equality, forbids the rich as well as the poor to sleep under bridges.” — Anatole France (Contextualized for the modern era, where the law now forbids the poor from sleeping anywhere at all.)

By 2026, the transformation was complete. The hostile bench with the center bar had been superseded by the hostile ordinance. Cities no longer needed to invest in expensive, defensive street furniture when a simple police citation could achieve the same exclusionary result. The legal landscape had become the ultimate hostile design, invisible to the eye but impassable to the destitute.

Psychological Impacts: How Defensive Design Erodes Social Trust and Community Cohesion

The Architecture of Anxiety

Urban planners often speak of “eyes on the street” as a metric for safety, yet modern city design increasingly replaces human presence with steel spikes and slanted aluminum. This shift towards defensive design does more than displace vulnerable populations; it actively reshapes the collective psyche of the city. When a public bench is engineered to be uncomfortable after ten minutes, the message transmitted to the public is one of inherent distrust. The environment signals that lingering is a crime and that relaxation is a privilege reserved for private spheres.

Psychological research from 2020 to 2026 highlights a growing “fortress mentality” among urban residents. A city that fortifies itself against its own citizens cultivates an atmosphere of paranoia. Walking past spikes embedded in window ledges or metal fins on concrete slabs triggers a subtle but constant fight or flight response. The landscape no longer invites cooperation but demands vigilance. This defensive posture transforms shared spaces into zones of transit rather than places of connection, effectively severing the social ties that bind a community together.

The Message of Exclusion

The psychological toll is heaviest on the marginalized, yet the impact ripples outward to affect every citizen. Reports from 2024 indicate that the criminalization of rough sleeping, reinforced by the UK Criminal Justice Bill and similar legislation globally, exacerbates feelings of alienation. When a person sees a bench designed to reject a human body, they witness a physical manifestation of empathy loss. This “exclusionary design” acts as a daily reminder that the city values aesthetics and order over human welfare.

For the unhoused, this results in what researchers call “spatial erasure.” It is not merely the loss of a place to rest but the removal of the right to exist in the public eye. However, the general populace also suffers from this erasure. The casual interactions that build social trust—the chance meeting on a park bench, the shared moment of rest between strangers—are engineered out of existence. Without these “soft” interactions, the “other” remains a stranger, and the stranger remains a threat.

Quantifying the disconnect

Data gathered between 2020 and 2025 suggests a correlation between hostile urban features and a decline in perceived community safety. Contrary to the intent of crime prevention, defensive architecture often increases fear. A 2023 study on urban design noted that residents in areas with heavy defensive modifications reported lower levels of trust in their neighbors. The logic is circular: if the environment suggests that people are dangerous enough to require spikes to deter, residents will treat one another with suspicion.

Furthermore, qualitative reports from 2025 highlight a “biophilic deficit” caused by these sterile environments. Humans possess an innate need for connection with soft, welcoming landscapes. The replacement of wooden slats with cold metal and the removal of planters to prevent sitting creates a sensory deprivation that heightens urban stress. The city becomes a machine for moving people, not a habitat for living.

The Erosion of Civil Society

The ultimate cost of defensive design is the erosion of civil society. Public spaces function as the living room of democracy. They are where diverse groups mix, mingle, and tolerate one another. By making these spaces hostile, authorities segregate populations and sanitize the urban experience. The 2024 discussions surrounding the Vagrancy Act revealed a deep societal fracture; the laws and the architecture work in tandem to render poverty invisible, allowing the advantaged to maintain a comfortable ignorance.

When the physical environment rejects the most vulnerable, it degrades the moral fabric of the entire community. A society that tolerates architecture designed to inflict pain or discomfort has accepted a baseline of cruelty. Reversing this trend requires more than removing spikes; it demands a reimagining of public space as a trust building infrastructure. We must choose designs that signal welcome rather than warning, fostering a city where belonging is a right, not a luxury.

Case Study: The Battle Against ‘Anti Rough Sleeper’ Features in London

The concrete landscape of London has quietly waged war on its most vulnerable citizens for over a decade. While the term hostile architecture entered the lexicon in the early 2010s, the period from 2020 to 2026 marked a fierce resurgence in the debate. This era saw a clash between council policy, rising homelessness figures, and a creative rebellion led by artists and activists. The battlefield was not just the steps of City Hall but the very benches, doorways, and bike racks that define the public realm.

The Silent deterrents

By 2020, the strategy of exclusion had evolved. The blatant metal spikes of 2014, which had caused public outrage, were largely replaced by more subtle designs. The Camden Bench, a sculpted block of concrete with angular surfaces designed to repel skateboarders and sleepers alike, remained the gold standard of this philosophy. Its influence spread. Throughout the early 2020s, Londoners noticed an increase in segmented seating, slanted perches, and rocky landscaping in sheltered alcoves. These features were often defended by authorities as necessary for “public safety” or “crime prevention,” yet their primary function was clear: to ensure no one lingered, especially those with nowhere else to go.

The Human Cost (2024 to 2025):

According to data from the Combined Homelessness and Information Network (CHAIN), London saw a record 13,000 people sleeping rough during the 2024 to 2025 period. Between April 2024 and March 2025 alone, 8,396 people were recorded sleeping on the streets for the first time, a sharp 5% increase from the previous year.

Creative Resistance and Design Hacking

As the statistics climbed, so did the resistance. The battle lines shifted in 2023 and 2024, moving from petition signatures to direct intervention. One standout example of this new wave of activism was the MyPowerBank project in 2023. Designer Luke Talbot created a pocket sized device allowing users to steal power from rental bikes. The device hacked the dynamo of Santander Cycles to charge mobile phones, a lifeline for homeless individuals denied access to the power grid. It was a functional protest, turning corporate street furniture into a public utility for the excluded.

The artistic pushback intensified in July 2024. Renowned artist Stuart Semple, a longtime critic of exclusionary design, launched the Stop Homelessness Spiking campaign. Partnering with creative agencies, Semple transformed existing metal studs into makeshift advertising spaces. They installed bespoke covers over the spikes, displaying images of people sleeping, effectively piercing the visual conscience of the city. This campaign did not just demand removal; it physically reclaimed the space, proving that hostile surfaces could be neutralized through ingenuity.

The Institutional Stance

Despite these interventions, the institutional grip remained tight. Westminster City Council and other local authorities faced immense pressure as rough sleeping numbers swelled. In late 2025, data showed over 4,000 people sleeping rough on a single night in London. The response from property developers and some councils was to double down on “defensive” measures to protect private assets from the growing crisis. While some high profile removals of spikes occurred due to bad press, the default approach for new developments continued to prioritize exclusionary design principles.

The battle for the benches of London is far from over. As we move through 2026, the friction between a city designed for flow and a population in desperate need of rest remains unresolved. The persistence of these features, despite record homelessness, suggests that hostile architecture is no longer just a design trend but a cemented policy of the modern metropolis.

Case Study: New York City’s Subway Seating Removal and Public Outcry

The transformation of the New York City subway system from a place of transit into a battleground for spatial control became undeniably visible in February 2021. For decades, the sturdy wooden benches on platforms served a simple purpose: rest. They offered relief to the weary nurse ending a shift, the elderly tourist navigating the city, or the parent clutching a sleeping child. Yet, at the 23rd Street station on the F line, those benches vanished overnight.

The removal might have passed as a routine maintenance update if not for a singular moment of digital candor. When commuters asked why the seating had disappeared, the official New York City Transit account on Twitter, now X, replied with blunt honesty. The agency stated the benches were removed to “prevent the homeless from sleeping on them.” This admission stripped away the usual bureaucratic euphemisms about “cleaning” or “modernization” and laid bare the intent behind the design. The backlash was immediate. Advocates for the unhoused, disability rights groups, and everyday riders condemned the move as cruel and shortsighted. The agency deleted the tweet and claimed it was an error, eventually returning some benches with dividers added to obstruct lying down. But the philosophy of exclusion had already taken root.

The Rise of the Leaning Bar

Between 2022 and 2025, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) pivoted from removing furniture to replacing it with “leaning bars.” These metal perches, installed at stations like West 4th Street, offer no true rest. They require the user to remain standing while propped against a narrow ledge. The design creates a hostile environment for anyone unable to stand for long periods.

The logic driving this shift is partly economic and partly exclusionary. In March 2025, MTA officials claimed a traditional wooden bench cost approximately 4000 dollars to install, whereas a metal leaning bar cost merely 450 dollars. This price difference provided a fiscal shield for a policy that effectively banned comfortable loitering. By prioritizing “flow” and “security” over comfort, the system began to filter its users based on physical ability.

Collateral Damage: The Accessibility Crisis

The removal of seating is often framed as a measure to control the unhoused population, yet the primary victims are frequently the disabled and the elderly. The Riders Alliance, a grassroots organization advocating for better transit, argued throughout 2024 that these designs violate the spirit of public accommodation. For a rider with chronic pain, a pregnant woman, or a senior citizen, a bench is not a luxury. It is a necessity for accessing the city.

“Making the subway less useful and less comfortable makes life harder for essential workers, people with disabilities, and everyone who depends on public transit.” — Danny Pearlstein, Riders Alliance.

While the MTA settled major lawsuits regarding elevator accessibility in 2022, promising access to 95 percent of stations by 2055, the concurrent removal of platform seating undermined these gains. An elevator allows a wheelchair user to reach the platform, but the lack of seating ensures the platform remains a physically taxing space for those with limited mobility who do not use wheelchairs.

The Escalation of 2025

The trend of hostile design accelerated in 2025 with the introduction of aggressive new barriers. At the 59th Street and Lexington Avenue station, the MTA installed spiked “sleeves” on turnstiles to prevent fare evasion. These jagged metal additions turned the station entrance into a fortress. Officials cited a loss of 350 million dollars in unpaid fares the previous year to justify the hardening of the infrastructure.

This evolution from bench removal to spiked gates paints a clear picture of the modern urban strategy. The goal is no longer to create a welcoming public commons but to engineer a space that repels “undesirable” behavior through physical discomfort. The subway, the circulatory system of New York, is being redesigned to ensure that no one lingers, no one rests, and no one feels too at home.

Resistance and Tactical Urbanism: Guerrilla Mattress Installation and Spikes Removal

The urban landscape has become a silent battleground. On one side, city planners and private developers deploy “defensive design”—a euphemism for exclusionary structures meant to deter the unhoused. On the other, a loose coalition of artists, activists, and guerrilla urbanists engage in direct action to reclaim these spaces. Between 2020 and 2026, this resistance evolved from simple acts of vandalism into sophisticated campaigns of tactical urbanism, turning the very tools of exclusion into symbols of public failure.

The Legacy of the Mattress: From Comfort to Protest