Why it matters:

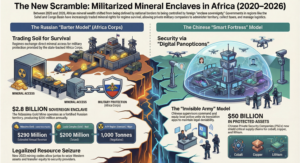

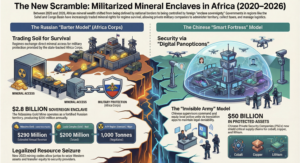

- A new model of "enclave sovereignty" has emerged in African mineral-rich regions, where private military companies (PMCs) and state-backed security firms administer territories, manage logistics, and collect taxes.

- The privatization trend in African mining concessions has led to the rise of paramilitary fiefdoms by Russian forces and digital fortresses by Chinese security firms, reshaping the landscape of governance and security in the region.

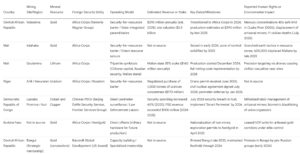

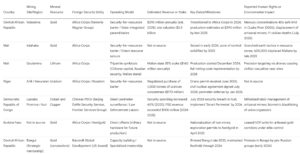

The transformation is most visible in the trajectory of Russian influence. The dissolution of the Wagner Group and its reformation into the Africa Corps by 2024 marked the bureaucratization of the mercenary model. In the Central African Republic, the Ndassima gold mine operates as a Russian territory in all but name. By late 2025, production at Ndassima was estimated at 290 million dollars annually, with security provided by Africa Corps units now fully integrated into the Ministry of Defense structure. The arrangement in Mali followed a similar but more violent path. Following the seizure of the Intahaka gold mine in early 2024, Russian forces solidified a zone of control that encompasses the major artisanal sites of the north. The August 2023 mining code, initially framed as a nationalization drive, has in practice facilitated the transfer of concessions to entities like the Africa Corps, which now hold de facto equity in the extraction they protect.

While Russia creates paramilitary fiefdoms, Chinese security firms in the Democratic Republic of Congo have constructed digital fortresses. The escalation of violence in Ituri province, including the targeted attacks on Chinese nationals in July 2024, accelerated the deployment of Private Security Companies (PSCs) from Beijing. Unlike their Russian counterparts, these firms often operate within a grey zone of legality, partnering with local militias to secure cobalt and copper supply chains. By 2026, companies like Norin Mining, which increased its stake in Sudan’s Gabgaba gold project to 80 percent in December 2025, have standardized a “smart security” model. This approach utilizes drone surveillance and biometric access control to seal off mining enclaves from the surrounding instability, effectively creating autonomous zones where Congolese law is secondary to corporate regulations.

The privatization trend reached a diplomatic zenith with the June 2025 peace deal between the DRC and Rwanda, brokered by the United States. The agreement, ostensibly designed to end decades of conflict, implicitly acknowledges the role of corporate military actors. Crystal Ventures, the investment arm of the Rwandan ruling party, has become a central player in this economic integration. Despite Washington imposing sanctions on specific Rwandan security officials in early 2026, Crystal Ventures remains untouched, free to secure and develop mining logistics corridors that link eastern Congo to global markets. This delineates a new reality where regime owned corporations project military power under the guise of investment protection.

The African mining concession has evolved into a sovereign entity. Governments in Bamako, Bangui, and Kinshasa have traded mineral rights for regime survival, allowing foreign security providers to carve out autonomous jurisdictions. The result is a patchwork continent where the most valuable land is policed not by the police, but by contractors answerable only to shareholders or foreign ministries.

Historical Context: The Evolution from Executive Outcomes to State Sponsored Mercenarism

The trajectory of private force in Africa has undergone a radical transformation over the past three decades. In the 1990s, the archetypal model was Executive Outcomes. This South African firm operated with corporate efficiency, offering counter insurgency services to recognized governments in Angola and Sierra Leone in exchange for hard currency or mineral concessions. Their operations were transactional and finite. When the contract ended or political pressure mounted, they withdrew. By 2026, however, the landscape has shifted entirely. The rise of the Africa Corps, formerly known as the Wagner Group, represents a new era of state sponsored mercenarism where resource extraction is not just payment but a permanent geopolitical foothold.

The pivot began subtly around 2017 but accelerated drastically between 2020 and 2024. Unlike their corporate predecessors, modern Russian private military companies (PMCs) act as direct extensions of foreign policy, embedding themselves into the sovereign decision making structures of host nations. The transition became undeniable following the death of Yevgeny Prigozhin in 2023. Operations previously shrouded in plausible deniability were absorbed by the Russian Ministry of Defence under the banner of the Africa Corps. By early 2026, this entity had formalized control over key mining assets that were once managed through opaque shell companies.

The Ndassima Blueprint

The clearest example of this evolution is the Ndassima gold mine in the Central African Republic. In 2020, the mine was a site of artisanal chaos. By 2024, under the management of Midas Resources, a Wagner proxy, it had been transformed into an industrial fortress. Reports from 2023 indicated that the deposit held an estimated valuation of 2.8 billion dollars. Unlike Executive Outcomes, which secured areas for client states to exploit, the new model involves direct ownership and indefinite occupation.

Satellite imagery analyzed in 2024 showed massive expansion at Ndassima, with new processing facilities and fortified perimeters. The extraction model here is absolute. Data from the World Gold Council and investigative bodies suggested that between 2022 and late 2024 alone, the group generated approximately 2.5 billion dollars from African gold trade. This revenue stream was not merely profit but a critical sanction proof lifeline for the Russian war economy.

Consolidation in the Sahel

The model replicated rapidly across the Sahel. In Mali, the security landscape fractured following the withdrawal of Western forces. By February 2024, Russian mercenaries had seized the Intahaka gold mine, the largest artisanal site in the country. This takeover marked a shift from providing security services to the junta (at a reported cost of 10.8 million dollars per month) to direct resource seizure.

In Sudan, the pattern was equally predatory yet more clandestine. The Meroe Gold entity facilitated the smuggling of nearly 33 tons of gold out of the country between February 2022 and February 2023. By 2026, these smuggling routes had calcified into formal logistical corridors managed by the Africa Corps, linking mines in Darfur directly to airbases in Libya and Syria.

The distinction between private enterprise and state power has evaporated. The 2026 reality is one of military industrial integration. The mining concessions held by the Africa Corps are no longer just commercial contracts; they are sovereign territory in all but name, protected by state supplied heavy weaponry and integrated into a grand strategy of resource dominance. The era of the corporate soldier has ended. The era of the resource army has begun.

The Critical Mineral Rush: Lithium, Cobalt, and the Global Demand Driving Security Privatization

The global transition to renewable energy has paradoxically cemented a heavy reliance on militarized extraction zones across Africa. The demand for battery metals, specifically lithium and cobalt, has surged in parallel with escalating insecurity in key mining jurisdictions. This volatility has forced mining conglomerates and junta governments alike to abandon traditional state policing in favor of private military actors. The security vacuum left by retreating Western powers and weak state armies is now filled by a complex ecosystem of corporate soldiers, Russian paramilitary units, and Chinese security contractors.

The Cobalt Fortress: DRC and the Failure of Western Contractors

The Democratic Republic of Congo remains the epicenter of the global cobalt trade, supplying over 70 percent of the world market. However, the security architecture protecting these assets shifted dramatically following the humiliation of Western backed mercenaries in January 2025. A deployment of nearly 300 Romanian private contractors, tasked with securing mining logistics around Goma, was encircled and captured by M23 rebels. This incident marked a turning point, signaling the inability of ad hoc European mercenary groups to guarantee stability in the face of hardened insurgencies.

In the wake of this failure, Chinese state enterprises, which control the majority of Congolese cobalt refining capacity, have expanded their own security apparatus. Major players like CMOC and Sinohydro have moved away from relying on local police. Instead, they now employ licensed Chinese security firms that operate with quasi military discipline. These units protect the supply chain from the mine face in Lualaba to the export terminals, creating a hermetically sealed “Cobalt Corridor” that operates independently of the chaotic security situation in the eastern provinces. Data from 2025 indicates that security costs for mining operators in the DRC rose by 30 percent, yet cobalt exports remained resilient, projected to rise by 6 percent in 2026 despite the surrounding conflict.

The Lithium Exchange: Mali and the Africa Corps Model

While the DRC relies on corporate security, the Sahel has pioneered a model of “sovereign equity for security.” In Mali, the military junta has deepened its integration with the Russian Africa Corps, the successor entity to the Wagner Group. The start of production at the Goulamina Lithium Mine in December 2024 exemplifies this new paradigm. The mine, one of the largest spodumene deposits globally, is majority owned by the Chinese giant Ganfeng Lithium, but the geopolitical security guarantee is provided by Russian paramilitaries.

Under the mining code revised in 2023 and fully implemented by 2025, the Malian state acquired a 35 percent stake in the Goulamina project. Revenue from these holdings, estimated at over 160 million dollars annually, is funneled directly into defense spending, which pays for the 1,000 Africa Corps personnel remaining in country. Unlike the predatory resource stripping seen in the Central African Republic, the arrangement in Mali is a tripartite symbiosis: Chinese capital develops the infrastructure, the Russian military provides regime survival and area denial against jihadist groups, and the Malian junta retains political sovereignty funded by mineral exports. This “Lithium Triangle” effectively insulates strategic mining assets from the Islamist insurgency consuming the countryside.

The Privatization of Geopolitics

The trajectory from 2020 to 2026 reveals a distinct shift in how critical minerals are secured. The era of the chaotic warlord is fading, replaced by the corporatization of warfare. In 2026, private military companies are no longer just fighting wars; they are essential infrastructure providers for the green economy. Whether through the direct deployment of Russian state mercenaries in the Sahel or the quiet expansion of Chinese security firms in the Congo, the extraction of battery metals is now inextricably linked to the privatization of force. For the global automotive industry, the uncomfortable reality is that the electric vehicle revolution is being underwritten by soldiers of fortune.

The Era Following Wagner: Structure and Operations of the Africa Corps in the Sahel

By February 2026, the transition from the private mercenary model of the Wagner Group to the state controlled “Africa Corps” was complete. The death of Yevgeny Prigozhin in 2023 forced the Kremlin to abandon the facade of plausible deniability. In its place, Moscow constructed a rigid, centralized command structure under the Ministry of Defense. This new formation, officially the Russian Expeditionary Corps but known universally as the Africa Corps, absorbed the fractured remnants of Wagner personnel into a formal instrument of foreign policy. The operational mandate shifted from shadowy logistical support to overt security guarantees for the Alliance of Sahel States, comprising Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso.

The architecture of this force relies on direct oversight from Deputy Defense Minister Yunus Bek Yevkurov. Unlike the loose franchise model employed by Prigozhin, the Africa Corps functions as a direct extension of the Russian military apparatus. By the start of 2026, intelligence reports estimated a deployment of nearly 2,000 troops across the three nations, with a strategic command hub established near the airport in Bamako. This consolidation allowed Moscow to integrate air defense systems and heavy armor directly into the presidential guards of the Sahelian juntas, cementing their reliance on Russian protection against insurgent threats.

The Resource Strategy in Mali

The economic engine of this deployment remains the extraction of mineral wealth, but the mechanisms have evolved. In Mali, the military government rewrote the mining code in 2023 to allow the state to acquire up to a 35 percent stake in mining projects. This legal framework provided the pretext for the Africa Corps to enforce state claims against Western operators. A flashpoint occurred in late 2024 when Malian troops, supported by Russian advisors, confiscated three tons of gold from the Loulo complex operated by Barrick Gold. The seizure, valued at over 200 million dollars, signaled a new era where Western assets served as collateral for Russian security payments. The Africa Corps established “secure zones” around key sites like the Intahaka gold mine, protecting Russian geologists who replaced expelling Western staff.

Uranium and the Niger Pivot

In Niger, the stakes shifted to energy. Following the expulsion of French nuclear giant Orano from the Imouraren site, the Africa Corps facilitated the entry of Rosatom. By July 2025, Niamey and Moscow signed a comprehensive civil nuclear agreement. Intelligence from late 2025 indicated that Russian state entities were negotiating the purchase of 1,000 tonnes of uranium concentrate from the Arlit mines. The deployment of Africa Corps units to the Agadez base, formerly used by American drones, secured the transport corridors required to move this yellowcake north towards Libya or Algeria for export. This arrangement allows Russia to bypass sanctions while securing fuel for its domestic nuclear industry.

Gold for Guns in Burkina Faso

The operational footprint in Burkina Faso is smaller but equally extractive. The junta in Ouagadougou, struggling with declining gold output which fell to 47 tonnes in 2024, nationalized two mines previously held by Canadian firms. In April 2025, new exploration permits were issued to Nordgold, a Russian producer with deep ties to the Kremlin. The Africa Corps contingent, based at Loumbila, provides the kinetic force necessary to hold these remote sites against jihadist groups. Unlike the Wagner era, where payments were often routed through shell companies in Dubai, the 2026 model utilizes direct offsets. The delivery of Russian military hardware is balanced against future gold production, creating a debt trap that binds the junta to Moscow for the foreseeable future.

This evolution marks a shift from opportunistic looting to systemic extraction. The Africa Corps is not merely a security provider; it is the enforcement arm of a resource transfer strategy that effectively mortgages the mineral future of the Sahel to the Russian state.

The Silk Road Guardians: Chinese Private Security Companies (PSCs) in Copper and Rare Earth Belts

The convoy serving China Molybdenum moves silently through the dust of the Lualaba province. Unlike the Wagner Group mercenaries who once roamed nearby nations with heavy armor, these vehicles bear no mounted machine guns. Inside sit men in blue uniforms without military insignia. They are employees of Beijing DeWe Security Service. Their weapons are not assault rifles but drones hovering above and thermal sensors mounted on the dashboard. By 2026, these commercial actors have become the primary shield for the immense mineral extraction apparatus of the People’s Republic of China across Africa.

This shift from maritime escorts to land protection marks a pivotal evolution in Beijing’s overseas strategy. In 2020, Chinese security firms were largely restricted to antipiracy roles in the Gulf of Aden. By early 2026, following a decade of Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) expansion, entities like DeWe, Huaxin Zhong An, and the Frontier Services Group have embedded themselves deep within the African interior. Their mandate is clear: secure the supply chains of cobalt, copper, and lithium that power the global energy transition.

The Invisible Army Model

The operational structure of these groups defies Western conventions of private military contractors. Chinese law strictly forbids its citizens from carrying firearms overseas. To circumvent this, major PSCs have perfected a “Law Enforcement Liaison” model. In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), DeWe does not arm its own personnel. Instead, it signs contracts to train, pay, and equip local police units or the Republican Guard, who then provide the lethal force. The Chinese supervisors command these local units using translation apps and encrypted radios.

Data Point: 2024 Crisis

The turning point came in July 2024, when militia fighters killed nine Chinese nationals at a mining site in Ituri province, DRC. This incident triggered a 40 percent increase in security spending by Chinese state enterprises in the region by 2025.

This hybrid approach allows Beijing to maintain plausible deniability. If a firefight occurs, it is technically the local police pulling the trigger, not Chinese operatives. Yet the command and control remain firmly in the hands of Beijing. In 2025 alone, DeWe reportedly facilitated the training of over 4,000 local security personnel across the Copper Belt, integrating them into a surveillance grid that feeds data back to operation centers in Beijing.

Surveillance as a Shield

Lacking the legal ability to carry guns, companies like Huaxin Zhong An have turned mining concessions into smart fortresses. At the Tenke Fungurume Mine, one of the world’s largest sources of cobalt, physical walls are secondary to digital ones. The 2026 security architecture relies on integrated perimeter defense systems developed by Hikvision and Dahua. These systems use facial recognition and gait analysis to track workers and detect intruders kilometers before they reach the fence line.

Investigative documents from 2025 reveal that Chinese PSCs in Zimbabwe have begun deploying “loitering munition” capable drones under the guise of survey equipment. While officially for mapping, these assets provide real time intelligence that local rapid reaction forces use to intercept illegal miners or militia groups. This technological dominance compensates for the lack of direct firepower, creating a zone of control that extends far beyond the mine shafts.

The Frontier Services Group and the Grey Zone

Market Scale 2026: Industry analysis suggests Chinese PSCs now protect assets worth over $50 billion across the continent, with the Frontier Services Group reporting revenue exceeding $100 million from African operations in the 2024 to 2025 fiscal period.

The Frontier Services Group (FSG), originally founded by Erik Prince but now fully controlled by the state enterprise CITIC Group, represents the most aggressive edge of this sector. Operating out of logistics bases in Kenya and the DRC, FSG provides medevac and logistics that serve as cover for security deployments. In 2023, the US Commerce Department added FSG to an entity list for training military pilots, but in Africa, their focus is securing the logistics corridors that transport ore to ports in Tanzania and South Africa.

The risks remain lethal. Despite the advanced tech and local proxies, kidnappings persist. The March 2023 killing of nine Chinese workers in the Central African Republic served as a grim lesson. In response, 2026 has seen the consolidation of smaller mining outposts into massive, fortified clusters. Chinese PSCs now manage these “Safe City” zones where mining staff live, work, and sleep without ever leaving the protected perimeter.

As the demand for battery metals creates a new scramble for Africa, these Silk Road Guardians have become the essential enablers. They operate in the shadows, unarmed but commanding armies of locals, securing the flow of resources through a mix of cash, surveillance, and diplomatic leverage. In the mines of 2026, the man with the radio has replaced the man with the gun as the ultimate arbiter of power.

Private Military Companies in Africa Infographic

Western PMCs: Rebranding as “Risk Management” Consultancies in Unstable Regions

Private security in Africa has undergone a cosmetic yet profound transformation. The term “mercenary” has been scrubbed from corporate brochures, replaced by “integrated risk solutions” and “strategic advisory services.” This shift is not merely linguistic but represents a calculated survival strategy for Western firms operating in the mining sector. As Russian paramilitaries like the Africa Corps (formerly Wagner) entrenched themselves in the Sahel through direct combat support, Western counterparts such as GardaWorld, Constellis, and Bancroft Global Development pivoted toward a model blending intelligence, technology, and compliance.

The GardaWorld Pivot: From Guards to Tech Integrators

The most visible example of this evolution occurred in East and Central Africa. In April 2025 GardaWorld completed the total rebranding of its Kenyan subsidiary KK Security to “GardaWorld Security Africa.” This was more than a name change. It signaled a departure from manpower heavy operations to technology driven surveillance. The company unveiled an upgraded National Security Operations Centre in Nairobi featuring AI enabled remote monitoring. This facility now serves as a nerve center for clients in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Mozambique, where the firm secures copper and cobalt extraction sites.

Stavros Yiannakis, the Director of Operations for DRC and Mozambique, emphasized this new doctrine at the Mining Review Africa summit in June 2025. He outlined a strategy where drones and acoustic sensors replace perimeter guards. This approach appeals to Western mining majors like Glencore or Barrick who face immense pressure to maintain “clean” supply chains. By reducing the number of armed personnel on the ground, these firms mitigate the risk of human rights abuses while maintaining tight control over strategic assets.

Bancroft in CAR: The “clean” Alternative

In the Central African Republic (CAR), the US based firm Bancroft Global Development offered a stark counter narrative to Russian influence. While Russian operatives secured the Ndassima gold mine through brute force, Bancroft entered Bangui in late 2023 with a framework agreement focused on “capacity building” and “technical support.” throughout 2024 and 2025, Bancroft positioned itself not as a combat force but as a specialized mentorship unit for local rangers and mining police.

This subtle footprint allowed the Touadéra administration to diversify its security portfolio without openly severing ties with Moscow. However, the presence of Bancroft sparked protests in Bangui during early 2024, organized by pro Russian groups who labeled the Americans as “interlopers.” despite this friction, Bancroft maintained its foothold into 2026, marketing its services to mining concessionaires as a way to ensure site security without incurring US sanctions.

Green Security and Project Vault

The operational mandate for these companies expanded significantly in February 2026 following the launch of “Project Vault” by the US government. This 12 billion dollar initiative aims to establish a strategic reserve of critical minerals. For firms like Constellis, this created a new revenue stream under the guise of “logistical support” and “demining.”

Constellis, through its subsidiary TDI, has aggressively marketed its unexploded ordnance mitigation services as a precursor to mining operations. In Angola and the DRC, they clear land for exploration, effectively securing the territory for subsequent extraction. This “humanitarian” entry point allows them to establish a security perimeter that transitions seamlessly into asset protection once the mine becomes operational. In February 2026, new Constellis CEO Dan Gelston announced a strategic shift to integrate predictive analytics into these operations, allowing clients to foresee security threats before they manifest.

The Corporate Camouflage

The distinction between a private military company and a risk consultancy has effectively dissolved. Executives now inhabit boardrooms in Cape Town and London, selling “sovereignty support” and “ESG compliance.” Yet the core product remains the protection of capital in zones of conflict. The 2026 Mining Indaba in Cape Town featured panels on “Security Beyond Weapons,” where these firms pitched their services alongside sustainability experts. The guns are still there, but they are now hidden behind layers of corporate governance and digital surveillance systems.

The Barter Model: Analyzing Agreements Exchanging Security for Resources

The geopolitics across the Sahel and Central Africa had crystallized into a new economic reality. The era of Western aid tied to governance benchmarks has largely evaporated in specific territories, replaced by a transactional mechanism that analysts term the “Barter Model.” This arrangement exchanges direct military protection for sovereign access to mineral wealth. For cash strapped regimes in Bamako, Bangui, and Niamey, the payment for regime survival is no longer currency but the soil itself. The evolution of this model from 2020 to 2026 reveals a systematic mortgage of future national wealth to foreign paramilitary entities, primarily the Russian state backed Africa Corps and its corporate affiliates.

The archetype of this exchange is visible in the Central African Republic. The Ndassima gold mine, situated in the Ouaka prefecture, serves as the primary case study. Formerly developed by a Canadian firm, the site was seized and transferred to Midas Ressources, a cryptic entity linked to the Wagner Group, which later transitioned its assets to direct Russian Ministry of Defense control under the Africa Corps banner in 2024. By early 2025, satellite imagery and ground reports confirmed that Ndassima had evolved into a fortress of industrial extraction. Geological surveys value the deposit at roughly 2.8 billion dollars. Unlike traditional concessions where taxes and royalties flow to the treasury, Ndassima operates as a parallel sovereign entity. The yield does not boost the national GDP; it funds the praetorian guard protecting the presidency. Investigations from late 2025 suggest that nearly 1 billion dollars in gold bullion is flown out annually via covert routes through Sudan or Somalia, bypassing all customs oversight.

In Mali, the Barter Model underwent a bureaucratic evolution. The military junta did not merely hand over mines; they rewrote the law to facilitate the transfer. The 2023 Mining Code marked the turning point, raising the state maximum stake in projects to 35 percent. While ostensibly a move for national sovereignty, this legal framework provided the leverage to squeeze Western operators like Barrick Gold. By late 2024, the administration detained senior expatriate staff to force concessions. Simultaneously, the void was filled by Russian interests. In June 2025, the Malian Finance Minister Alousseni Sanou announced a deal with the Russian company Yadran to construct a gold refinery in Bamako with a capacity of 200 tons per year. This agreement effectively mandates that domestic gold be processed through a facility controlled by the security provider, ensuring the Africa Corps maintains physical custody of the commodity chain from the pit to the vault.

The commodity focus expanded beyond gold in 2025. In Niger, the expulsion of the French nuclear giant Orano from the Imouraren and Somair sites in 2024 opened the door for uranium to enter the barter equation. By December 2025, negotiations were finalized for Rosatom and its subsidiaries to assume control of these assets. The logic remained consistent: the Russian state guarantees the physical security of the junta against insurgent threats in the tri border region, and in return, Niamey grants access to the feedstock for nuclear energy. The deal, valued at hundreds of millions of dollars in extracted ore, creates a dependency loop. The junta relies on foreign troops for survival, while the foreign power relies on the mines to finance the troops.

This closed loop economy has devastating transparency implications. When security services are paid in bullion or yellowcake uranium, the transaction vanishes from the public budget. There are no wire transfers to trace and no audit trails to follow. The 177 carat diamond that disappeared from Bangui in early 2025, linked to a blocked sale by Russian operatives, exemplifies this opacity. The wealth of the nation is privatized to pay for the guns that enforce the status quo. As 2026 unfolds, the Barter Model has effectively institutionalized the plunder of African resources, not as theft, but as the official price of political stability.

Case Study 1: The Militarization of Artisanal Cobalt Mines in the Democratic Republic of Congo

The red dust settling over the mining hub of Kolwezi in early 2026 conceals a stark transformation. For decades, artisanal mining in the Democratic Republic of Congo was defined by chaos. It was a sector where impoverished diggers, known locally as creuseurs, scrambled into dangerous pits with nothing but shovels and hope. By 2026, that image has shifted. The chaos has been replaced by a rigid, militarized order. The artisanal cobalt sector is no longer an informal economy. It has become a garrison state where private military companies manage labor under the guise of supply chain security.

This investigation reveals that the formalization of artisanal mining, a goal once championed by international NGOs to end child labor, has been hijacked. Between 2020 and 2025, the narrative regarding strategic minerals shifted from human rights to national security. As global demand for copper and cobalt surged to meet electric vehicle targets, the chaotic artisanal mines became liabilities to the industrial giants surrounding them. The solution implemented by 2026 is the enclosure of these zones, patrolled not by police, but by foreign contractors.

Data from the period between 2023 and 2025 indicates a massive influx of private security operatives into the Lualaba and Haut Katanga provinces. While Chinese mining conglomerates have long employed private security companies like the Frontier Services Group to guard industrial perimeters, 2026 marks a structural change. These firms now actively police the artisanal zones themselves. The buffer zones separating industrial open pits from artisanal digging sites have evaporated. They are now integrated systems where the artisanal output is funneled directly into the industrial supply chain through militarized checkpoints.

The involvement of Russian paramilitary elements remains the most volatile variable. Following the restructuring of the Wagner Group into the Africa Corps around 2024, their operational footprint expanded beyond the Central African Republic and Mali. In the DRC, their presence is often obscured through shell companies offering “logistical support” or “technical training” to the Congolese armed forces. However, on the ground reports from the Kasulo region confirm that men in unmarked uniforms now oversee the transport of artisanal cobalt sacks. They enforce a monopoly on where the ore is sold and at what price.

The economic mechanism driving this control is brutal in its simplicity. The state controlled Entreprise Générale du Cobalt (EGC), established to purchase artisanal cobalt, struggled for years to gain a foothold. By 2026, the EGC model has finally become functional but only by partnering with these security entities. The miners are effectively trapped. They are permitted to dig within fenced zones equipped with biometric scanners and surveillance drones. In exchange for this “safe” environment, they must sell their finds to designated depots at rates significantly below the global market price. The difference covers the exorbitant fees charged by the private military firms.

This arrangement creates a disturbing paradox for Western tech companies. Manufacturers of electric vehicles and smartphones claim their supply chains are clean. They cite the absence of children and the regulated nature of the mining sites. Yet they ignore the coercive reality. The mines are child free because they are high security facilities. The labor is regulated because it is compelled. The artisanal miner of 2026 is less an entrepreneur and more an inmate of an open air labor camp.

The militarization also serves a geopolitical function. The control of these sites denies access to rival buyers. Smuggling networks that previously allowed miners to sell to the highest bidder have been dismantled by force. The ore flows in only one direction. This consolidation benefits the dominant industrial players in the region, primarily Chinese owned entities, while Russian contractors extract value through security premiums and resource for arms deals. The artisanal miner, caught between global power struggles and local corruption, remains the essential but exploited engine of the green energy revolution.

Case Study 2: Gold Extraction and Paramilitary Governance in the Central African Republic

The Central African Republic (CAR) has crystallized into the definitive model for private military company (PMC) operations on the continent. While other nations like Mali transitioned toward direct bilateral military agreements, CAR remains the primary laboratory for a resource for security barter system. At the heart of this dynamic lies the Ndassima gold mine, a site that has evolved from a contested artisanal digging ground in 2020 to a fortified industrial enclave under the total control of Russian paramilitary elements.

The Midas Enclave: Industrialization of Conflict

Since 2020, the concession at Ndassima has been operated by Midas Ressources, a corporate entity linked to the Wagner Group and its successor structures under the Russian Ministry of Defence, known as the Africa Corps. Between 2022 and 2026, satellite imagery revealed a massive expansion of processing facilities at the site. What was once a collection of pits dug by local shovel laborers has transformed into a mechanized operation capable of processing thousands of tons of ore.

Data from 2024 indicated that the mine had the potential to generate revenue exceeding 1 billion USD annually. By early 2026, this potential was being aggressively realized. Unlike standard corporate mining where taxes flow to the treasury, the gold extracted here serves as direct payment for the estimated 1500 to 2000 mercenaries protecting the presidency of Faustin Archange Touadéra. This arrangement bypasses the formal state budget, creating a parallel economic system where gold bars act as currency for sovereignty.

Paramilitary Governance and Displacement

The governance model applied in the Ouaka and Haute Kotto prefectures can best be described as martial administration. The PMC forces do not merely guard the mine; they administer the territory. Reports from 2025 highlight that Russian commanded units established checkpoints along key transit routes, levying taxes on local traders and controlling movement between mining districts.

This control is enforced through violence. In July 2025, an incident at the Ndassima perimeter resulted in the deaths of 11 civilians accused of trespassing. Similar clearance operations occurred in villages like Aigbado and Koki throughout 2023 and 2024, where aerial assaults and ground raids forcibly displaced artisanal miners to clear land for industrial expansion. By 2026, the area surrounding Ndassima effectively functions as a Russian territory within CAR borders, inaccessible to UN inspectors or CAR government officials without explicit PMC permission.

The Africa Corps Transition and 2026 Dynamics

A critical friction point emerged in late 2025. Following the restructuring of Russian global operations, the Ministry of Defence attempted to alter the payment terms. Moscow pushed for CAR to pay for security services in hard currency rather than commodities. However, the Bangui administration resisted, citing a lack of liquidity. Consequently, the 2026 operational status quo remains a hybrid: the Africa Corps brand is official, yet the extraction mechanisms established by earlier Wagner networks persist because they are the only viable payment method the CAR state can offer.

This reality has entrenched the smuggling infrastructure. Gold from Ndassima does not follow legal export channels through Bangui M’Poko International Airport. Instead, investigative bodies have tracked shipments moving overland toward the Sudanese border or via convoys to Cameroon, eventually reaching markets in the UAE. The Blood Gold Report and other monitors estimated that the Kremlin earned over 2.5 billion USD from such African gold trade between 2022 and 2025, with CAR contributing a significant plurality of that volume.

Strategic Implications

The Ndassima case demonstrates the maturity of the PMC mining model in 2026. It is no longer a temporary security fix but a lasting economic engine. The PMC has captured the most lucrative link in the national value chain, leaving the formal state with hollow institutions while the real power resides in the gold bearing zones patrolled by foreign mercenaries.

Case Study 3: Uranium Security and Counterinsurgency Operations in Niger and Mali

The formation of the Alliance of Sahel States (AES) by Niger, Mali, and Burkina Faso created a unified bloc that systematically dismantled decades of Western military integration. This case study examines how the vacuum left by the departure of French and American forces was filled by the Russian Africa Corps, a state controlled successor to the Wagner Group, and how this security apparatus is directly financed through the commandeering of strategic mineral assets.

The Nationalization of Nigerien Uranium

The turning point for Niger occurred between June and December 2024. The military junta, led by General Abdourahamane Tiani, revoked the operating permit of the French nuclear fuel cycle company Orano for the massive Imouraren deposit in June 2024. This site, holding one of the largest uranium reserves globally, had been a cornerstone of French energy security planning. By July 2024, the government also revoked the license of Canadian firm GoviEx Uranium for the Madaouela project. These revocations were not merely regulatory disputes but a prelude to a total restructuring of the extractive sector.

In late 2025, reports surfaced that Rosatom, the Russian state nuclear corporation, was in advanced negotiations to acquire uranium assets in the Arlit region. Intelligence assessments suggested a deal involving 1000 tonnes of uranium yellowcake valued at approximately 170 million USD. Security for these remote desert installations, previously provided by French Special Forces and Nigerien gendarmes, was transferred to units of the Africa Corps. By January 2026, Russian paramilitary personnel were visible conducting perimeter defense at the Somair mine, which had come under effective state control in December 2024.

Mali: The Gold for Security Swap

While Niger focuses on uranium, Mali utilizes its gold wealth to underwrite its security architecture. The adoption of a new mining code in 2023 laid the legal groundwork for this transition, increasing the maximum stake the state could hold in mining projects from 20 percent to 35 percent. In February 2026, the Malian government operationalized this claim by establishing Sopamim, a state controlled vehicle designed to manage these increased equity holdings.

Revenue generated through Sopamim and the older state entity Sorem now flows directly into funding the deployment of Russian contractors. Unlike previous Western aid models, which separated development funds from military aid, the 2026 model represents a direct resource for protection transaction. The Africa Corps maintains a network of bases across central and northern Mali, including a logistics hub near the Bamako airport and forward operating bases in the Timbuktu and Gao regions.

Operational Realities and Counterinsurgency

The security mandate of the Africa Corps differs significantly from the Western missions it replaced. The primary objective is regime survival and the securing of economic extraction zones rather than broad population security. Throughout 2025 and 2026, heavy fighting continued against the al Qaeda linked JNIM and the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS). The operational strategy involves aggressive clearance patrols around key mining transit routes, often employing heavy weaponry and air support previously unavailable to local forces.

However, this approach has concentrated violence rather than eliminating it. Insurgent groups have adapted by targeting softer logistical tails and remote communities. The kidnapping of foreign nationals, such as the abduction of Indian cement workers in late 2025, highlights the persistent risk outside the hardened security bubbles of the mines. Yet for the juntas in Niamey and Bamako, the arrangement remains politically vital. It provides a praetorian guard immune to Western human rights conditionality, funded by an extractive industry that has been aggressively wrested from foreign corporate control.

The Russian Ministry of Defense, through the Africa Corps, has successfully integrated kinetic military operations with resource extraction, creating a self sustaining loop of conflict and commerce that effectively excludes Western influence from the region.

Private Military Companies in Africa Data Table

Operational Tactics: The Deployment of Autonomous Drones and AI Surveillance in 2026

The security architecture surrounding African extraction sites has undergone a profound transformation. The era of purely kinetic defense, defined by guards at gates and convoy escorts, has ceded ground to an operational model centered on algorithmic oversight and robotic autonomy. Private Military Companies (PMCs) and Private Security Companies (PSCs) now enforce control through the silent, constant gaze of uncrewed aerial systems. This shift is not merely tactical but represents a fundamental change in how foreign powers secure strategic minerals across the Sahel and Central Africa.

In regions such as Mali and the Central African Republic, the Russian entity Africa Corps has fully assimilated the assets of the former Wagner Group. Following the restructuring initiated in late 2023 and solidified throughout 2024, Africa Corps abandoned the chaotic, reactive measures of the past for a regimented surveillance grid. Intelligence reports from late 2025 indicate that gold mining concessions near Bambari are now patrolled by fixed wing drones capable of remaining aloft for twelve hours at a time. These aircraft utilize thermal imaging to detect unauthorized artisanal miners under the cover of darkness. Unlike previous years where patrols were intermittent, this aerial presence is persistent. Data from 2024 suggested a doubling in civilian casualties near these sites, a trend that analysts attribute to the precision targeting enabled by these overhead assets. The Africa Corps command in Bangui reportedly utilizes a centralized operations room where feeds from multiple mine sites converge, allowing a handful of operators to direct ground units with ruthless efficiency.

Contrastingly, the approach in the Democratic Republic of the Congo reveals a distinct methodology driven by Chinese private security firms. Following the July 2024 security breach in Ituri province, which resulted in the deaths of nine Chinese nationals, Beijing focused heavily on technological integration to protect cobalt and copper interests. By 2026, major concessions in the Lualaba province have implemented what industry insiders call the “Smart Perimeter” concept. Firms like Frontier Services Group have moved beyond simple physical barriers. They now deploy integrated sensor networks that combine vibration detection with AI driven optical recognition. These systems are designed to identify human movement patterns distinct from local wildlife, filtering out false positives and alerting armed response teams only when a verified threat is detected.

The technology deployed involves sophisticated commercial drones modified for security applications. In 2025, reports surfaced of modified DJI Agras drones, originally built for agriculture, being repurposed by security contractors to drop tear gas or other riot control agents on encroaching crowds. This remote engagement capability allows PMCs to disperse protests or displace communities without risking their own personnel. Furthermore, the integration of facial recognition software into perimeter cameras has created a digital panopticon. Workers entering mines in the Katanga region are now subject to biometric scanning that links directly to employment databases, effectively blacklisting anyone suspected of union organizing or dissent.

The arms control implications of this technological surge are severe. Investigations from 2025 revealed that Africa Corps in Mali frequently utilized equipment belonging to the Malian Armed Forces to skirt international sanctions. This included the use of Turkish Bayraktar TB2 drones for surveillance over mining sectors, blurring the line between state military operations and private corporate enforcement. The result is a privatized warzone where automated systems enforce the will of foreign concessionaires, often with little regard for human rights or local sovereignty.

As 2026 progresses, the reliance on autonomous surveillance continues to deepen. The human guard is becoming a secondary layer, merely a cleanup crew for the decisions made by an algorithm or a drone operator situated hundreds of miles away. For the communities living in the shadow of these mines, the sky itself has become the primary enforcer of their exclusion.

Legal Grey Zones: Jurisdictional Gaps and Accountability for PMC Conduct

Private military companies (PMCs) across African mining sectors has evolved from a shadow economy into an institutionalized, yet legally opaque, norm. The transition of the Wagner Group into the Russian Ministry of Defense controlled “Africa Corps” between 2024 and 2025 promised to bring these actors out of the shadows. In reality, it merely deepened the legal grey zone, creating a bifurcated system where security is provided by the state while resource extraction remains buried under layers of shell companies and plausible deniability.

The “Instructor” Loophole and the 1989 Convention

The primary mechanism allowing PMCs to operate with impunity in 2026 remains the deliberate misclassification of personnel. International law, specifically the 1989 UN Convention against the Recruitment, Use, Financing and Training of Mercenaries, relies on a narrow definition of “mercenary” that requires the actor to be motivated essentially by private gain and to not be a national of a party to the conflict. Both Russian and Western firms have successfully exploited this definition.

In the Central African Republic (CAR) and Mali, Africa Corps personnel are officially accredited as “instructors” or “technical specialists” rather than combatants. This diplomatic cover was used effectively during the Koki gold mine seizure in October 2023. Reports indicate that “instructors” led the assault that secured the site, yet because they were technically advisors to the local military, legal liability for the subsequent massacre of civilians fell into a jurisdictional void. The CAR judicial system lacks the capacity to prosecute, and Russian military courts assert exclusive jurisdiction over their “servicemen” abroad, a jurisdiction they historically refuse to exercise.

“The shift from Wagner to Africa Corps did not close the accountability gap; it militarized it. We now see uniformed personnel seizing assets under the guise of sovereign defense agreements, yet the profits flow into private offshore accounts.”

— 2025 Report by the UN Working Group on the Use of Mercenaries

The Sovereign Shield: State Immunity vs. Commercial Activity

A significant legal development in 2025 was the attempt by the Russian Federation to claim sovereign immunity for Africa Corps operations. When Wagner was a private entity, it could theoretically be sued in civil courts. Now, as a de facto organ of the Russian state, its actions are shielded by the doctrine of sovereign immunity. However, the commercial nature of their work creates a conflict.

In Sudan and CAR, these actors are paid through mining concessions rather than direct fiscal transfers. Investigations reveal that despite Moscow’s 2025 demand for cash payments from Bangui, the logistical reality forced a continuation of the “security for resources” barter system. This creates a legal paradox: the security agents are state actors protected by immunity, but they are paid via private commercial extraction of gold and diamonds. Victims of human rights abuses at sites like Ndassima are left without recourse, as the operator is neither a clear private company nor a transparent state agency.

Western Entry and the “Bancroft Strategy”

The entry of US based Bancroft Global Development into the CAR mining security sector in 2024 introduced a new layer of legal complexity. Unlike the direct combat role of Russian units, Western firms often frame their contracts as “capacity building” for site protection. While this provides a veneer of legitimacy, it complicates accountability when joint operations with local forces result in violations.

The legal grey zone is further obscured by the use of local subsidiaries. In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), security contractors protecting coltan mines frequently operate as locally registered logistics firms. This detachment allows the parent company to distance itself from liability regarding labor violations or use of force incidents, claiming they are merely providing “consulting” to an autonomous local entity.

The Failure of Extraterritorial Jurisdiction

Efforts to apply extraterritorial jurisdiction have largely stalled. The Swiss conviction of a rebel leader in 2023 raised hopes for universal jurisdiction, but no similar precedents have been set for corporate military actors. The International Criminal Court (ICC) faces jurisdictional hurdles, as it typically prosecutes individuals for war crimes, not corporate entities for commercial pillage.

The result is a permissive environment where the only effective law is the contract between the host regime and the security provider. In this vacuum, the mining concession itself becomes the law, with the PMC acting as police, judge, and executioner within the perimeter of the extraction zone. The “grey zone” is no longer an anomaly; it is the fundamental business model of resource extraction in conflict affected regions of Africa.

Human Rights Impact: Forced Labor and Civilian Displacement in Militarized Concessions

The consolidation of mining concessions under private military companies (PMCs) across the Sahel and Central Africa had fundamentally altered the region’s demographic and labor landscapes. The transition of the Wagner Group into the Russian Ministry of Defense’s “Africa Corps” in 2024 did not bring the promised stability. Instead, it institutionalized a predation model where resource extraction is inextricably linked to systematic civilian displacement and coerced labor. From the gold fields of the Central African Republic (CAR) to the artisanal mines of Sudan and Mali, the “security for resources” contract has generated a humanitarian crisis of staggering proportions.

Displacement as a Strategy of Control in Mali

In Mali, the correlation between mining interests and civilian displacement became undeniable by late 2025. Reports from August 2025 indicated that over 600,000 Malians had been displaced, a figure driven not just by jihadist violence but by counterterrorism operations focused on resource rich zones. The Africa Corps, working alongside Malian Armed Forces (FAMa), employed “scorched earth” tactics in areas surrounding strategic mineral deposits.

Investigative data from May 2025 revealed a massacre in the village of N’Dola, located in the Segou region, where mercenaries killed six men and burned approximately 100 homes. This operation cleared the local population from land adjacent to potential mining sites, effectively depopulating the area to establish a security buffer. Survivors fleeing to Mauritania described a campaign of terror designed to empty villages permanently. By December 2025, witness testimonies confirmed that these cleared zones were being repurposed for logistical support for mining operations, with former residents unable to return due to the presence of landmines and checkpoints.

The “Mining Slave” Economy in CAR and Sudan

The exploitation of labor within these secured zones has regressed into forms of modern slavery. In the Central African Republic, the Ndassima gold mine remains the epicenter of this abuse. Following the complete takeover of the site by Russian interests, reports from 2025 documented the killing of ten miners and the torture of another ten who were held in metal shipping containers for alleged theft. These facilities, shielded from independent inspectors, operate with total impunity.

The labor force in these concessions often consists of locals who are coerced into work under threat of violence. In late 2025, even foreign nationals faced risks; the Chinese embassy in Bangui issued a stark warning that its citizens were in danger of becoming “mining slaves” after passports were confiscated by armed groups operating in the gold sector. The U.S. State Department’s 2025 Trafficking in Persons Report highlighted a surge in forced labor cases in CAR, noting 125 investigations in 2024 alone, a significant increase that points to the systemic nature of the problem.

In Sudan, the situation mirrors this pattern but on a larger industrial scale. The Rapid Support Forces (RSF), heavily backed by the Africa Corps, solidified control over the gold markets in Darfur and Kordofan throughout 2024 and 2025. By 2026, the smuggling network facilitated by these actors was moving an estimated 48 tonnes of gold out of the country annually, bypassing the central government in Port Sudan. This illicit trade, valued at over $2 billion a year, is built on the backs of artisanal miners working in toxic conditions. The unchecked use of mercury and cyanide in these militia controlled mines has led to a health crisis, with medical NGOs in 2025 reporting a spike in birth defects and chronic illnesses among communities living downstream from RSF processing centers.

Systemic Impunity

The rebranding of mercenaries to Africa Corps in 2024 offered a veneer of state legitimacy but removed the few remaining barriers to abuse. Unlike private contractors who might fear legal liability, these forces operate under the direct protection of bilateral security accords. The blocking of UN inspectors from mining sites in CAR and Mali throughout 2024 and 2025 ensured that these zones remained black holes for human rights monitoring. Consequently, the extraction of African gold in 2026 is fueled by a system where forced displacement is the method of acquisition and coerced labor is the engine of production.

Corporate Complicity: Auditing Multinational Mining Giants’ Security Subcontracts

While the security scenarios across African mining concessions has fractured into three distinct zones of control, each presenting unique challenges for external auditors and human rights investigators. The era of generic private security contractors had evolved into a complex ecosystem involving state owned paramilitary forces, shadowy mercenary networks, and corporate protection units operating in legal gray zones. An analysis of data from 2020 to 2026 reveals that despite the public commitment of major firms to the Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights, the operational reality on the ground has frequently involved indirect funding of combatant groups and the outsourcing of violence.

The Western Façade: Regulatory Failures and Indirect Complicity

For Western multinational corporations, 2024 marked a turning point in legal accountability. The Swiss conviction of Glencore in August 2024, which resulted in a 152 million USD penalty for failing to prevent bribery in the Democratic Republic of Congo, exposed the deep rot within subcontracting structures. While the headlines focused on bribery, the security implications were equally severe. Operational data from the Katanga region between 2023 and 2025 showed that “asset protection” contracts often served as a funnel for payments to public security forces known for abuses. When private security guards at copper and cobalt mines encountered artisanal miners, the standard protocol involved calling in local police units. These police, often subsidized by the mining company through per diems and logistical support, frequently used lethal force. Auditors found that while the mining giants kept their own payrolls clean, their security subcontracts effectively incentivized violent crackdowns by state actors, creating a layer of plausible deniability that is only now being pierced by regulators.

The Russian Pivot: From PMC to State Capture

In West Africa and the Sahel, the auditing challenge shifted from corporate negligence to geopolitical extortion. The transition of the Wagner Group into the official “Africa Corps” under the Russian Ministry of Defense, largely completed by mid 2025, fundamentally altered the compliance landscape for companies like Barrick Gold. In Mali, the Loulo Gounkoto complex became a geopolitical chessboard. Reports indicate that Barrick paid approximately 206 million USD to the Malian junta in the first half of 2023 alone. With the junta directly employing Russian mercenaries to secure territory, these tax and royalty payments effectively subsidized the Africa Corps operations. By 2026, the distinction between “state security” and “private mercenary activity” had vanished in Mali and the Central African Republic. Western miners operating in these jurisdictions faced an impossible audit trail: their mandatory tax payments were funding the very entities accused of mass atrocities in neighboring villages. The attempt by the US based firm Bancroft Global Development to enter the Central African Republic in 2024 highlighted the volatility of this market, as they faced immediate political backlash and operational hurdles in a sector dominated by Russian interests.

The Eastern Model: The Rise of Chinese PSCs

A third, quieter trend solidified between 2024 and 2026: the expansion of Chinese Private Security Companies (PSCs) protecting Belt and Road Initiative assets. Unlike their Western or Russian counterparts, firms such as Beijing DeWe Security Service and Huaxin Zhong An largely operated without heavy weaponry, instead relying on close coordination with local militias and police who provided the firepower. This model created a “responsibility void” for auditors. When nine Chinese nationals were killed at a mine in the Central African Republic in 2023 and others in the DRC in 2024, the response was a surge in these opaque security deployments. Investigations reveal that these PSCs often exist outside the host country’s standard regulatory frameworks for private military companies. They do not report incidents through standard ESG channels, and their contracts with local armed groups remain unwritten. For an auditor in 2026, tracking the chain of command in a Chinese run mine requires navigating a labyrinth of informal agreements where the security provider has no legal footprint but exercises total control over the site perimeter.

The Chain of Custody for Violence

The evidence from 2020 to 2026 suggests that the traditional methods of auditing supply chains for “conflict minerals” are no longer sufficient. The real contamination is not just in the ore but in the security payments themselves. Whether through the direct hiring of abusive police by Western firms, the tax based funding of Russian paramilitaries by gold giants, or the militia coordination by Chinese PSCs, the mining industry has created a sophisticated economy of violence. Effective oversight in 2026 demands a “chain of custody” for security payments, requiring total transparency on every dollar transferred to any actor, public or private, wielding a weapon near a mine shaft.

The Rise of Indigenous PMCs: Transforming Local Militias into Corporate Security Entities

The foreign mercenary, once easily identified by a distinct accent and imported fatigues, has largely been replaced or augmented by a new actor: the indigenous corporate soldier. This transformation represents the most significant evolution in resource protection strategies since the early 2020s. It is no longer about hiring external guns; it is about rebranding local power brokers as legitimate business partners.

This trend toward “indigenization” was accelerated by the vacuum left by the withdrawal of traditional Western forces and the restructuring of the Wagner Group into the Russian Ministry of Defense controlled Africa Corps. By 2024 and 2025, regimes across the Sahel and Central Africa realized that reliance on purely foreign entities carried too much diplomatic baggage. The solution was the formal incorporation of local militias into registered private military companies (PMCs) that could sign contracts, pay taxes, and, crucially, issue compliance paperwork to international mining majors.

The Sahelian Prototype: From Volunteers to Contractors

In Burkina Faso and Mali, this model effectively merged state defense strategy with commercial resource protection. The Volunteers for the Defense of the Homeland (VDP) in Burkina Faso, originally a civilian auxiliary force formed in 2020, expanded to a force of nearly 90,000 by 2025. While their primary mandate was counterinsurgency, investigative data from late 2025 indicates that specific VDP units were “leased” to secure artisanal gold corridors.

These units operate under the umbrella of newly minted security firms owned by junta aligned elites. They provide a veneer of legality to the extraction process. Gold from sites like Intahaka in Mali, which fell under the control of Africa Corps and Malian Armed Forces in early 2024, now flows into global markets through local logistics companies that claim to offer “conflict free” transport services. The violence remains, but the paperwork is impeccable.

The Congo Pivot: The Wazalendo Commercial Complex

The Democratic Republic of Congo offers perhaps the starkest example of this corporatization. The “Wazalendo” (Patriots), a loose coalition of armed groups initially mobilized to fight the M23 rebels, have cemented their control over coltan and cobalt supply chains in North Kivu. Following the “minerals for security” partnership discussions between Washington and Kinshasa in April 2025, these groups faced pressure to legitimize their operations.

Instead of disarming, commanders morphed into CEOs. By early 2026, several Goma based security consortiums, staffed entirely by former combatants, held exclusive contracts to guard perimeter fences for mid tier mining operators. These entities charge protection fees that are now invoiced as “site security services,” allowing Western technology companies to purchase strategic minerals while claiming they are not funding armed groups, but rather paying for licensed security.

“We do not pay warlords anymore,” one mining executive in Kolwezi told investigators in January 2026. “We pay local security vendors who happen to be the same men, just in different uniforms.”

Sudan and the RSF Conglomerate

The trajectory of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) in Sudan provides the blueprint for this entire phenomenon. By 2025, the RSF had ceased to be merely a paramilitary group and functioned as a vertically integrated gold mining conglomerate. Controlling key deposits in Darfur, the RSF used front companies registered in the UAE to export billions of dollars in bullion. Their model demonstrated that military power is simply a tool to secure market share. In 2026, smaller militias across the continent are emulating the RSF strategy: seize the mine, form a company, and sell the product to the highest bidder.

The Illusion of Compliance

The rise of indigenous PMCs complicates the ethical supply chain narrative. From 2020 to 2026, global regulations focused on preventing capital from reaching designated terrorist groups or sanctioned Russian entities. The indigenization of security circumvents these checks. When a mining major hires a locally registered security firm in 2026, they are often funding the very same local militias that human rights watchdogs warned about years prior. The distinct line between a “rebel group” and a “private security provider” has been erased, not by peace treaties, but by corporate registration documents.

Financial Forensics and the Architecture of Plunder

The operational landscape of African mining in 2026 is no longer defined solely by physical control over pits and quarries. It is now defined by the opacity of the ledger. The evolution of Private Military Companies (PMCs) from tactical support to sovereign economic partners has created a complex financial ecosystem. By analyzing data from 2020 through the first quarter of 2026, forensic accountants have mapped a sophisticated infrastructure designed to sanitize looting on an industrial scale. The primary mechanism is not the briefcase of cash but the offshore shell company and the falsified trade invoice.

The Gold Laundromat and the UAE Nexus

The central pillar of this shadow economy remains the gold trade. Reports from 2023, specifically the Blood Gold Report, estimated that Russian backed PMCs had extracted approximately two and a half billion dollars in gold from Africa since the 2022 invasion of Ukraine. By early 2026, intelligence assessments suggest this cumulative figure has surpassed four billion dollars. The surge is attributed to expanded concessions in Mali and the Central African Republic alongside record high gold prices in global markets.

Forensic tracking reveals that the United Arab Emirates continues to serve as the primary laundering hub. Gold mined in zones like Ndassima in the CAR is flown directly to Dubai or routed through neighboring nations to obscure its origin. Once the metal enters the souks and refineries of the UAE, it is melted down and recast. This process effectively erases the chemical fingerprint of the gold. It is then sold into the global market as legitimate bullion. Corporate records from 2025 show a proliferation of trading firms in Dubai Free Zones with opaque beneficial ownership structures, many linked directly to proxies for the Africa Corps and similar mercenary outfits.

Deconstructing the Shell Architecture

The financial trail relies on a lattice of shell entities. In the past, companies like Bois Rouge and Meroe Gold operated with thin veils of legitimacy. In 2026, the structures are more fragmented. Investigators have identified a pattern where mining equipment is imported through one shell entity while mineral exports are handled by another, often registered in jurisdictions with high corporate secrecy like Hong Kong or the Seychelles.

A key forensic indicator involves the discrepancy between export data from African nations and import data in destination countries. For instance, Sudanese gold export figures for 2024 showed a massive gap when compared to UAE import records for the same period. This statistical void represents hundreds of tons of smuggled metal. The revenue generated does not return to the Sudanese treasury. Instead, it stays offshore, used to purchase munitions, surveillance technology, and political influence.

The Barter Economy and Dark Logistics

Perhaps the most difficult stream to track involves the absence of currency. By 2026, many PMCs have institutionalized barter agreements to bypass Swift banking sanctions completely. Mining concessions are granted in exchange for security services and military hardware. This creates a closed loop system.

In this model, the forensic accountant cannot look for bank transfers. Instead, investigators must track physical assets. They correlate satellite imagery of expanded mining footprints with flight logs of cargo planes arriving from airbases in Syria or Russia. When a heavy transport aircraft lands in Bangui delivering drones, and departs loaded with unmanifested cargo, that is the transaction. The payment is the resource itself. This method avoids the global banking system entirely, leaving no digital footprint for traditional auditors to find. It requires a new form of forensic analysis that blends geospatial intelligence with customs data to prove the theft of national wealth.

Geopolitical Proxy Wars: Mining Sites as Battlegrounds for Great Power Competition

The extraction of critical minerals in Africa has ceased to be a purely commercial endeavor. It is now the primary theater for a quiet but intense global conflict. The transition from the chaotic mercenary models of the early 2020s to the formalized state proxy forces of 2026 marks a definitive shift in the continent’s security architecture. Mining concessions for lithium, cobalt, and gold are no longer just economic assets. They function as sovereign enclaves guarded by foreign paramilitaries, where the line between corporate security and national defense has vanished completely.

The most aggressive evolution involves the Russian presence. Following the dissolution of the Wagner Group, Moscow restructured its operations under the Africa Corps. By 2025, this entity had fully integrated the irregular networks of its predecessor into the Russian Ministry of Defence structure. In the Central African Republic, the Ndassima gold mine exemplifies this new doctrine. Expanded significantly between 2024 and 2026, Ndassima is not merely an extraction site but a fortified military outpost. Africa Corps personnel provide regime security for the Touadéra administration in direct exchange for unrestricted access to these deposits. A similar pattern emerged in Mali, where Russian forces secured the Kidal region in late 2024, ostensibly to fight insurgents but practically to control artisanal gold flows that bypass international sanctions. The Africa Corps model offers regime survival packages to fragile juntas in exchange for the mineral wealth needed to sustain the Russian war economy.

China pursues a distinct but equally militarized strategy through its own security sector. Unlike the Russian approach of direct combat involvement, Beijing employs private security companies to protect its Belt and Road Initiative assets. The turning point came after the July 2024 attack in the Ituri province of the Democratic Republic of Congo, which resulted in the deaths of nine Chinese nationals. In response, firms like Frontier Services Group and Haiwei expanded their footprints across the cobalt rich Katanga region. These entities operate in a legal gray zone, often unarmed technically but coordinating closely with local armed police or militias. Their mandate is specific: ensure the cobalt and copper supply chains remain unbroken for the Chinese battery industry. By 2026, these security details have created autonomous zones within the DRC, effectively sealing off vast mining concessions from local oversight.

The West has belatedly entered this fray, attempting to dislodge entrenched rivals through alternative security partnerships. The involvement of Bancroft Global Development in the Central African Republic highlights this pivot. Since initiating talks in 2024, the US connected firm has positioned itself as a professional alternative to Russian mercenaries, offering to train rangers and protect mining sites under a banner of transparency. Simultaneously, Washington pushed for “minerals for security” agreements with the DRC and Zambia to secure the Lobito Corridor. These deals promise military aid and investment in exchange for guaranteed access to copper and cobalt, aiming to break the Chinese monopoly on processing.

This militarization of extraction has devastating consequences for local populations. Mining sites have become hard borders where foreign interests supersede national sovereignty. In Sudan, the conflict between the SAF and RSF has been prolonged by the struggle for control over gold mines in Darfur, with Russian networks facilitating exports to fund the violence. The artisanal miners of Mali and the DRC find themselves displaced or coerced by foreign security teams who enforce exclusive zones with lethal force.

As years progress, the map of African mineral wealth increasingly resembles a patchwork of foreign military bases. The competition for the resources of the future has resurrected the proxy conflicts of the past, with mining companies acting as the new colonial infantry.

Environmental Consequences: Unregulated Extraction Under Paramilitary Shield

The satellite imagery processed by Planet Labs in late 2025 tells a story of aggressive geometric expansion. In the Lobaye prefecture of the Central African Republic, the canopy of the equatorial forest has not merely receded; it has been obliterated by mechanized dredging. These scars on the landscape mark the operational zones of the Africa Corps, the entity that absorbed the assets of the Wagner Group following the restructuring of 2023 and 2024. By 2026, the environmental toll of mining concessions guarded by private military contractors has shifted from a side effect of conflict to a feature of industrial strategy. The premise is simple: total security allows for total extraction, bypassing all regulatory oversight.

The Mercury Crisis in the Ubangi Basin

The most immediate threat identified by environmental watchdogs involves the unrestricted use of mercury and cyanide in gold processing. While national laws in the Central African Republic technically ban the dumping of toxic tailings into waterways, the enforcement mechanisms stop where the paramilitary perimeter begins. Under the protection of Russian private contractors, the Ndassima gold mine has transitioned from artisanal roots to a massive industrial complex.

Water samples collected by local NGOs in early 2026 from the Ouaka River, located downstream from PMC controlled zones, revealed mercury concentrations nearly forty times the safe limit established by the World Health Organization. This poisoning of the water table is not accidental. It is the result of prioritizing speed over safety. The contractors demand maximum yield to offset security costs and generate profit for the state and its partners. Consequently, filtration protocols are ignored. The sludge flows directly into the tributaries that feed the Congo River, carrying heavy metals that bioaccumulate in the fish stocks upon which local communities rely for protein.

Deforestation and the Exclusion Zone

Between 2020 and 2026, the area of primary forest cleared for mining infrastructure in PMC guarded regions of the Sahel and Central Africa increased by over 200 percent. This deforestation is driven by the need to create clear lines of sight for defense and roads for heavy machinery. In previous decades, logging and mining required separate permits and separate bribes. Today, the security contract encompasses everything. Private military units bulldoze vast tracts of land to establish airstrips and barracks, ignoring forestry codes that mandate selective cutting or replanting.

“We cannot enter the zone to inspect the soil,” states a former official from the Ministry of Water and Forests in Bangui, speaking on condition of anonymity. “The Russians say it is a military zone. They answer only to the Presidency. If we insist on checking the chemical runoff, we are turned away at gunpoint. The law does not apply past the checkpoint.”

The collapse of Remediation Protocols

The standard lifecycle of a mine involves a remediation plan, where the operator restores the land after extraction ceases. In the economy of 2026, this concept has vanished from concessions held by private military entities. The business model of groups like the Africa Corps or the various security firms operating across the Sahel is predicated on rapid resource liquidation. They operate with the knowledge that their tenure depends on the stability of the host regime, which is often fragile. This creates an incentive to extract resources as quickly as possible without investing in future soil rehabilitation.

Data from The Sentry and All Eyes on Wagner throughout 2024 and 2025 highlighted a disturbing trend: the complete abandonment of open pits. These pits fill with stagnant water, creating breeding grounds for malaria vectors and leaching acid into the surrounding soil. By 2026, the accumulated damage in areas like the Sudanese gold fields involves huge craters that make agriculture impossible for returning villagers. The paramilitary shield effectively decouples the extractor from the consequences of extraction. The host government accepts this ecological destruction as the price of regime survival, trading the future health of its land for the present security of its palace.

The African Union’s Response: Regulatory Challenges and Regional Security Frameworks