Public Sector Bank Loans: The NPA Crisis and Corporate Cronyism

Why it matters:

- The original vision for Indian public sector banks as custodians of national welfare has shifted towards aggressive corporate lending, leading to massive write offs.

- While the banks have made strides in financial inclusion with millions of Jan Dhan accounts, a significant portion of these accounts remain inactive, questioning the real impact on the rural poor.

The original covenant between the Indian state and its public sector banks was simple yet profound. These institutions were envisioned not merely as commercial entities but as custodians of national welfare, tasked with banking the unbanked and funding the infrastructure that would drive the economy forward. By early 2026, the sheer scale of this mandate had become staggering. With a branch network penetrating the deepest rural hinterlands, led by the State Bank of India with over 22,640 branches alone, the reach of these institutions remains unmatched by any private competitor.

However, an investigative look into the data from 2020 to 2026 about Public Sector Bank Loans reveals a disturbing duality. While the public face of these banks champions financial inclusion for the poor, their balance sheets tell a story of aggressive corporate lending that went sour, necessitating massive write offs to sanitize the books. The mandate, it seems, has shifted from development to damage control.

The Inclusion Façade

On paper, the inclusion story is a triumph. By August 2025, the Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana had amassed over 56.16 crore accounts, mobilizing deposits worth Rs 2.67 lakh crore. This immense volume suggests that the public sector banks successfully fulfilled their role as the primary vehicle for financial enfranchisement. Yet, a closer inspection exposes the cracks in this foundation. As of September 2025, government data indicated that nearly 26 percent of these accounts were inoperative. Approximately 142.8 million accounts sat dormant, acting more as statistical trophies than functional financial tools for the poor.

Public Sector Bank Loans

The Corporate Pivot and the Clean Up

While the banks were busy opening zero balance accounts for the poor, their lending arms were entangled in a much higher stakes game with corporate India. The period between 2020 and 2026 witnessed a dramatic “clean up” of balance sheets, a euphemism for removing bad loans to present a healthier financial picture.

By March 2025, the Gross Non Performing Asset (GNPA) ratio of public sector banks had miraculously dropped to 2.58 percent, a stark improvement from the double digit highs seen a decade prior. Superficially, this signals robust health. The government cited net profits of Rs 1.78 lakh crore for financial year 2025 as proof of a turnaround. But this profitability was purchased at a steep price.

The mechanism behind this recovery was not just better collection, but aggressive write offs. Between financial year 2021 and financial year 2025, public sector banks wrote off approximately Rs 5.82 lakh crore in bad loans. In fiscal year 2021 alone, Rs 1.33 lakh crore was erased from the books. Even in fiscal year 2025, as profits soared, another Rs 91,260 crore was written off.

The Cost of Cronyism?

This massive exercise in provisioning and writing off loans raises uncomfortable questions about who exactly these banks serve. The recovery rate for these written off loans hovered around a meager 28 percent over the five year period ending in 2025. This means that for every Rs 100 written off, the bank recovered less than Rs 30, while the borrower often a large corporate entity effectively walked away from the bulk of the liability on the bank’s main balance sheet.

The juxtaposition is stark. On one end, the “Mandate” pushes for small ticket loans to street vendors under schemes like PM SVANidhi. On the other, lakhs of crores lent to industrial giants vanish into the accounting abyss of “technical write offs.” The public sector bank thus finds itself in a precarious position: it is the primary lender for the nation’s infrastructure and the primary victim of its corporate delinquency.

As we move deeper into 2026, the narrative of “record profits” must be read with caution. The mandate has indeed been fulfilled in terms of reach and branch density, but the financial stability of these institutions has required a taxpayer funded bailout in the form of foregone loan recoveries. The banks have survived the crisis, but the structural flaw of corporate cronyism remains embedded in the lending culture, camouflaged by a pristine 2.58 percent GNPA figure.

Defining the Rot: Understanding Non Performing Assets (NPAs) And Public Sector Bank Loans

To the uninitiated observer, a bank balance sheet is a testament to stability. Yet, beneath the veneer of complex financial jargon lies a simpler, darker reality regarding how public money evaporates. The term Non Performing Asset (NPA) serves as a sanitary euphemism for a far messier concept: bad loans. These are not merely delayed payments or clerical errors. They represent capital that has ceased to generate income, money lent by state owned banks that has effectively stopped flowing back to the public treasury. In the context of the Indian banking sector between 2020 and 2026, understanding this definition is crucial to unmasking a systemic crisis that masquerades as a recovery.

The Mechanics of Default

Technically, an asset turns bad when the borrower stops paying interest or principal for ninety days. This ninety day rule is the tripwire. Once crossed, the loan slips from “Standard” to “Substandard,” then “Doubtful,” and finally “Loss.” However, this textbook progression hides the investigative reality. For years, corporate borrowers and compliant bank officials engaged in “evergreening,” a practice where fresh loans were issued solely to pay off old debts, keeping the account artificially standard. The rot was not sudden; it was carefully concealed until asset quality reviews forced the truth into the open.

The Illusion of Recovery: Data from 2020 to 2026

Official government data paints a picture of robust health. By March 2025, the Gross NPA ratio of Public Sector Banks (PSBs) had plummeted to approximately 2.58 percent, a stark improvement from the alarming 9.11 percent recorded in March 2021. On paper, this looks like a triumph of financial management. The absolute value of gross bad loans dropped from Rs 6.16 trillion in 2021 to roughly Rs 2.83 trillion by early 2025. Proponents of the current banking regime cite these numbers as proof that the crisis is over.

However, an investigative look at the “write off” mechanism reveals a different story. The reduction in bad loans was not primarily achieved through cash recovery but through technical deletions. Between 2014 and 2024, banks wrote off a staggering Rs 16.35 trillion (over 16 lakh crore rupees). In the fiscal year 2023 24 alone, PSBs removed Rs 1.14 lakh crore from their books. In the first half of fiscal year 2025, another Rs 42,035 crore vanished via this accounting trapdoor.

The Write Off Loophole

A “write off” allows a bank to remove a bad loan from its balance sheet, using profits to cover the loss. This reduces the reported NPA ratio, making the bank appear healthier to investors and rating agencies. While the government insists that borrowers remain liable, the recovery rate tells the true tale. Data suggests that recovery from written off accounts often hovers between 15 percent and 26 percent. This means for every 100 rupees removed from the books, the bank forfeits nearly 75 rupees forever. This massive erosion of capital is funded by the taxpayer, either through direct recapitalization using public funds or by eating into bank profits that would otherwise go to the state.

Corporate Willfulness

The core of this rot is not the struggling farmer or the small business owner but the “wilful defaulter.” These are entities that have the capacity to repay but choose not to, often diverting funds to other ventures or offshore accounts. As of March 2024, the number of wilful defaulters rose to 2,664, collectively owing Rs 1.96 lakh crore. This demographic represents the intersection of corporate impunity and banking negligence. While the gross NPA ratio falls, the absolute stock of money lost to such corporate delinquency remains a colossal drain on the national economy.

In summary, defining the rot requires looking past the headline ratio. The crisis of the 2020s was not solved; it was merely cleaned from the ledger. The bad loans did not turn good; they were simply erased, leaving the public to foot the invisible bill.

The Credit Boom: Origins of Irrational Exuberance

By February 2026, the Indian banking sector appeared to have turned a corner. On the surface, balance sheets were pristine, profitability was at decadal highs, and the gross non performing asset (GNPA) ratios had dipped to record lows. However, an investigative look beneath this polished veneer reveals that the origins of this newfound health lie not in prudent recovery but in a massive, systemic erasure of bad debt. The period from 2020 to 2026 witnessed a credit environment defined by two distinct phases: a ruthless cleanup of legacy corporate cronyism via write offs, followed immediately by a manic surge in unsecured retail lending that the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has frequently flagged as “irrational exuberance.”

The Cost of a Clean Slate

The narrative of the “Credit Boom” in the 2020s cannot be understood without acknowledging the debris of the previous cycle. Between the financial years 2020 and 2025, Public Sector Banks (PSBs) engaged in an aggressive exercise of cleaning their books. Official data presented to Parliament reveals that PSBs wrote off a staggering ₹6.15 lakh crore in bad loans from April 2020 to September 2025. These write offs, often defended as technical accounting measures, effectively removed toxic assets from the primary view of investors, creating an illusion of robust health.

While the books looked cleaner, the recovery from these written off accounts remained dismal. The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC), once touted as the ultimate resolution mechanism, saw its efficacy erode significantly during this period. By late 2025, data showed that creditors were taking haircuts as high as 67 percent to 73 percent on admitted claims. For liquidation cases, recovery rates plummeted to a mere 5 percent. This massive forfeiture of public money served as the foundation for the subsequent lending spree, effectively socializing the losses of the corporate cronyism era.

The Retail Rush: A New Bubble?

Freed from the burden of legacy NPAs, banks pivoted aggressively. The “exuberance” shifted from large industrial projects to the individual consumer. The period from 2022 to 2025 saw an explosion in unsecured credit: personal loans, credit cards, and consumer durable financing. This surge was so potent that the RBI Governor issued repeated warnings in 2023 and 2024 about the building stress in unsecured portfolios.

By December 2025, the RBI Financial Stability Report (FSR) noted that while overall stress appeared contained, the unsecured retail segment warranted “close vigilance.” The data validated these fears. Private sector banks accounted for over half of the fresh slippages in retail loans, yet PSBs were not immune, holding the largest share of Special Mention Accounts (SMA) in the unsecured category. The rush to lend had outpaced the growth of deposits, with credit growth hitting 20.6 percent in late 2023 before regulatory intervention cooled it to around 11 percent by November 2024. This mismatch created a liquidity tightness that exposed the fragility of the boom.

Persistent Cronyism

Amidst this retail frenzy, the ghosts of corporate cronyism remained exorcised only on paper. The list of wilful defaulters continued to grow, expanding from 2,154 in March 2020 to 2,664 by March 2024. As of early 2026, the top 50 wilful defaulters alone owed approximately ₹92,570 crore to the banking system. Prominent names like Gitanjali Gems and ABG Shipyard remained at the top of this list, with outstanding dues in the thousands of crores.

The “Credit Boom” of the 2020s, therefore, was not a story of genuine capital formation or industrial expansion. It was a cycle of financial engineering where the state absorbed the costs of past corporate malfeasance to finance a new, risky consumption bubble. The exuberance was irrational not because of the volume of credit, but because the systemic flaws—poor recovery rates, high write offs, and unchecked wilful default—remained unaddressed.

The Nexus of Politicians, Bureaucrats, and Corporate Tycoons

The intricate web connecting India’s political elite, entrenched bureaucracy, and industrial magnates has long defined the operational mechanics of the banking sector. Between 2020 to 2026, this unholy alliance evolved from simple loan favoritism into a sophisticated machinery of debt concealment and asset stripping. While the government proclaimed a massive cleanup of balance sheets, the underlying data reveals a different story: a systematic transfer of public wealth into private hands through the mechanism of loan write offs.

Public Sector Bank Loans Data

The Great Write Off Bonanza (2020 to 2026)

The primary tool for masking corporate cronyism has been the aggressive writing off of bad loans. By early 2026, data from the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) and Ministry of Finance revealed a staggering reality. In the five year period leading up to 2025, Public Sector Banks (PSBs) wrote off approximately ₹5.82 lakh crore. If we include private lenders, the total banking system erased nearly ₹8.90 lakh crore from their books.

Key Statistic: In the financial year 2024 to 2025 alone, state owned banks wrote off ₹91,260 crore. While this reduced the Gross Non Performing Asset (GNPA) ratio to a optically pleasing 2.58% by March 2025, it effectively removed these defaults from public scrutiny while the borrowers largely retained control of their empires.

The official narrative suggests these are merely technical measures. However, the recovery rate paints a grim picture. For every ₹100 written off during this period, banks recovered barely ₹28. The remaining loss is absorbed by the taxpayer, a direct subsidy to the corporate defaulter authorized by compliant bureaucrats and their political masters.

The Wilful Defaulter List: A Roll Call of Cronyism

By June 2024, the list of wilful defaulters i.e borrowers who have the means to pay but refuse to do sohad swelled to 2,664 entities owing ₹1.96 lakh crore. This list acts as a directory of political corporate power.

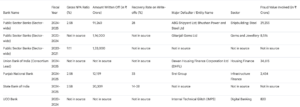

Topping the list was Gitanjali Gems, owing over ₹8,516 crore, a reminder of the diamond scandals that implicated high profile banking officials. Following closely was ABG Shipyard, with outstanding dues of ₹4,684 crore. The ABG case, involving a total fraud estimation of nearly ₹22,800 crore, exposed how consortium lending allowed a single entity to dupe 28 banks. Despite the arrest of its founder Rishi Agarwal in late 2022, the systemic lapses that permitted such massive leverage point to high level protection. These loans were not merely business failures; they were approved via a nexus that bypassed risk assessment protocols.

The Builder Banker Bureaucrat Triangle

In 2025, a significant legal development exposed the depth of this collusion in the real estate sector. The Supreme Court of India permitted the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) to register 22 regular cases investigating a specific “nexus” between banks and real estate developers. This probe focused on projects in the National Capital Region, Mumbai, and Bengaluru.

The scam operated on a subvention scheme model. Banks disbursed loans directly to builders on behalf of homebuyers, often without verifying project milestones. When builders defaulted, the liability fell on the buyers, while the funds had already been siphoned off. Bureaucrats in development authorities facilitated this by looking the other way regarding land permits and completion certificates. The court’s intervention in July 2025 highlighted that bank officials had colluded with developers to release funds for projects that existed only on paper.

Recycling Fraud: The Srei Group Case

Even as the system claimed to be reforming, new scandals emerged. In December 2025, Punjab National Bank (PNB) reported a fresh fraud of ₹2,434 crore linked to the Srei Group. This case emerged years after the insolvency proceedings began, raising serious questions about the oversight mechanisms in place between 2021 and 2025. The delay in classifying these accounts as fraud suggests a deliberate attempt by elements within the banking bureaucracy to shield specific corporate interests until the loss became impossible to hide.

The pattern is undeniable. A corporate tycoon donates to political causes; a bureaucrat approves a viable looking but structurally hollow loan; the politician ensures the regulator remains somnolent. When the loan inevitably sours, it is written off, the loss nationalized, and the cycle resets.

The period from 2020 to 2026 did not end the NPA crisis; it merely institutionalized the exit strategy for crony capitalists. The nexus remains the single biggest threat to the financial stability of the Indian banking system.

Dial a Loan: The Phenomenon of Political Interference

The phrase “Dial a Loan” has long haunted the corridors of India’s banking sector. It describes a culture where a phone call from a powerful politician or bureaucrat to a bank chairman was sufficient to approve multi crore rupee loans to favored corporations, often bypassing risk assessment protocols. While the central government asserts this era ended in 2014, the financial footprint of those decisions—and potentially new, subtler forms of influence—has dominated the banking landscape between 2020 and 2026. The crisis is no longer about the issuance of these loans but about their burial through massive write offs, a process that cleans bank balance sheets while costing the taxpayer billions.

The Great Cleanup or the Great Coverup?

From 2020 to 2026, Public Sector Banks (PSBs) engaged in an aggressive campaign to reduce their Gross Non Performing Assets (GNPA). On paper, this strategy was a resounding success. By September 2025, the GNPA ratio of scheduled commercial banks had dropped to a multi decade low of 2.1 percent. However, this immaculate surface hides a disturbing reality. The reduction was not primarily achieved through cash recovery but through “technical write offs.”

Between the financial years 2020 and 2025, PSBs wrote off approximately Rs 5.82 lakh crore in bad loans. In the fiscal year 2024 to 2025 alone, banks removed over Rs 91,260 crore from their asset books. A technical write off moves the bad loan to a separate ledger, removing the stigma of “default” from the headline numbers. While banks claim they continue to pursue recovery, the data suggests otherwise. The recovery rate for written off accounts during this period hovered at a dismal 18 percent to 28 percent. This means for every Rs 100 erased from the books, banks recovered less than Rs 30, effectively waiving the rest for corporate defaulters.

Corporate Cronyism in the 2020s

The “Dial a Loan” culture effectively morphed into a “Shield a Defaulter” mechanism. The primary beneficiaries of these massive write offs were not small farmers or MSMEs but large corporate entities. As of December 2024, data revealed that 29 unique borrower companies accounted for defaults exceeding Rs 1,000 crore each. These large accounts often linger in the system for years, protected by protracted legal battles and an Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC) process that has seen its recovery rates plummet.

The most glaring example of this legacy exploding in the current decade is the ABG Shipyard fraud. In February 2022, the CBI booked the company for causing a wrongful loss of Rs 22,842 crore to a consortium of banks led by ICICI Bank and the State Bank of India. While the loans originated earlier, the delay in classifying the fraud and the subsequent slow motion legal response raised serious questions about oversight. The timeline suggests that despite the “cleanup” narrative, the system remained vulnerable to manipulation, allowing promoters to divert funds for years before the law caught up.

The Invisible Hand of Influence

Political interference in the 2020 to 2026 period became less about ordering a loan sanction and more about influencing the resolution process. The sheer volume of haircuts—where banks agree to accept a small fraction of the debt owed—suggests a system still tilted heavily in favor of the corporate borrower. In several high profile IBC cases, banks accepted haircuts of up to 90 percent, leaving the public exchequer to absorb the loss. Critics argue that such leniency is impossible without tacit approval from the highest levels of the financial and political establishment.

Furthermore, the recapitalization of these banks acts as a direct transfer of wealth from the taxpayer to the corporate defaulter. When the government injects capital into a PSB to cover the hole left by a written off corporate loan, the ordinary citizen effectively pays the bill for the “phone banking” of the past. By 2026, while the banks celebrated record profits and pristine balance sheets, the structural cronyism that allowed the loans to turn bad had not been eradicated; it had merely been accounting engineered out of sight.

The legacy of “Dial a Loan” is not just a historical footnote. It is the defining feature of the 2020 to 2026 banking economy, visible not in the loans being made today, but in the massive, unrecovered fortunes being quietly erased from yesterday’s ledgers.

Due Diligence Failure: Collateral Overvaluation and Feasibility Gaps

The Mirage of Collateral

Collateral overvaluation remains the primary mechanism for loan fraud. In theory, secured loans are backed by assets that banks can liquidate if a borrower defaults. In practice, these assets are often phantoms or grossly inflated. Between 2020 and 2024, forensic audits across multiple state owned banks revealed a disturbing pattern where immovable properties were valued at rates 300% to 500% above their circle rates or fair market value. In some egregious instances reported in 2023, land parcels pledged as security for corporate loans were found to be agricultural land or litigation encumbered plots with negligible commercial value.

This “valuation gaming” allows corporations to access capital far beyond their creditworthiness. When the account turns into a Non Performing Asset (NPA), the bank discovers the security coverage is hollow. The Recovery of Debts and Bankruptcy Act provisions and SARFAESI actions become toothless because the underlying asset cannot cover even a fraction of the outstanding principal. The data supports this: despite aggressive recovery drives, PSBs recovered only roughly ₹1.65 lakh crore against a massive write off pool of approximately ₹5.82 lakh crore over the five years ending March 2025.

Feasibility Gaps and Project Fiction

Beyond the asset side, the liability side suffers from “feasibility gaps.” Due diligence requires banks to stress test the revenue projections of a borrower. However, in the era of crony capitalism, Detailed Project Reports (DPRs) are treated as gospel rather than speculative fiction. Large infrastructure and industrial loans sanctioned or restructured during the pandemic years often relied on revenue models that assumed best case scenarios for decades. Costs were underestimated, and demand was overestimated.

When external shocks hit—such as supply chain disruptions or input cost inflation—these fragile models collapsed. The “feasibility gap” is the distance between the borrower’s projected cash flow and the grim reality. Instead of flagging these gaps early, bank credit committees often engaged in “evergreening,” granting fresh loans to service old interest, thereby masking the default.

The FY25 Fraud Spike: A Lagging Indicator

The consequences of these due diligence failures are visible in the fraud statistics for the fiscal year 2025. According to the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) Annual Report data for FY25, while the volume of fraud cases dipped, the value involved surged by 194% to ₹36,014 crore. A significant portion of this spike, over ₹18,000 crore, came from the reclassification of older accounts as fraud. This time lag—often five to seven years between the loan sanction and the fraud declaration—proves that due diligence mechanisms failed at the point of origination.

Crucially, Public Sector Banks bore the brunt of this negligence, accounting for 70.7% of the total fraud amount in FY25. This disproportionate share highlights that state owned lenders remain far more susceptible to external influence and internal compromise than their private counterparts. The “advances related frauds” (loan frauds) constituted the highest value category, confirming that the big ticket corporate loans remain the primary vehicle for siphoning public money.

The Write Off Mechanism

When collateral proves worthless and projects fail, the final act is the “Technical Write Off.” In the fiscal year 2024 to 2025 alone, PSBs wrote off ₹91,260 crore. These write offs remove the bad loan from the balance sheet, artificially lowering the Gross NPA ratio to a multi year low of 2.58% by March 2025. However, this cosmetic improvement comes at the cost of the taxpayer. The capital base of the bank is eroded to absorb these losses, necessitating periodic recapitalization using public funds.

The cycle is enduring: loans are sanctioned based on inflated collateral and fictitious feasibility studies; the funds are diverted; the account defaults; and finally, the bank writes off the asset after a delay of several years. Until the due diligence process is insulated from corporate cronyism and third party complicity, the NPA crisis will continue to shapeshift, hiding behind write offs and delayed reporting.

The Great Balance Sheet Mirage: Public Sector Banks and the Evergreening Epidemic

Evergreening: Restructuring Loops to Conceal Defaults

By early 2026, the Indian banking sector appeared to have achieved a miraculous recovery. Official data painted a picture of robust health, with the Gross Nonperforming Asset (GNPA) ratio across Public Sector Banks (PSBs) dropping to a historic low of approximately 2.58 percent by March 2025. Yet, beneath this glossy surface lies a systemic rot, a financial sleight of hand known as evergreening. This mechanism has allowed banks to artificially maintain the appearance of asset quality while masking deep corporate distress, effectively transferring the cost of crony capitalism onto the public ledger.

The Mechanics of the Mirage

Evergreening is the practice whereby a lender extends fresh credit to a struggling borrower solely to enable them to repay previous debts. This restructuring loop prevents the loan from being classified as a default, maintaining the fiction of a performing asset. While traditional restructuring is a legitimate tool, the methods deployed between 2020 and 2024 evolved into complex financial engineering designed to evade regulatory oversight.

The most sophisticated conduit for this subterfuge was the Alternative Investment Fund (AIF). In this model, a bank would invest capital into an AIF. The AIF, in turn, would invest that same capital into a debtor company struggling to service its loans to the original bank. The debtor would then use these funds to repay the bank. The bank’s balance sheet would show a repaid loan and a new high grade investment, while the actual risk remained unchanged and unprovisioned.

The Regulatory Cat and Mouse Game

The scale of this regulatory arbitrage forced the Reserve Bank of India to intervene with a stern circular on December 19, 2023. The directive explicitly banned Regulated Entities from investing in any AIF scheme that had downstream investments in a debtor company of that lender. The central bank demanded that existing investments violating this rule be liquidated within 30 days or face 100 percent provisioning.

This crackdown exposed the depth of the rot. Industry estimates suggested that thousands of crores in corporate debt had been camouflaged through these structures. The priority distribution model used by some AIFs further skewed the risk, allowing senior investors to exit first while the banks (holding junior units) absorbed the losses, effectively subsidizing corporate defaults.

The Cost of “Cleaning” Books

While the RBI tightened norms on concealment, the primary method for reducing bad loan ratios remained the massive erasure of debt. Between the financial years 2020 and 2025, Public Sector Banks wrote off approximately INR 5.82 lakh crore. These were not waivers for small farmers but largely accounting entries for corporate defaulters. In FY24 alone, scheduled commercial banks wrote off over INR 1.70 lakh crore to clean their books.

- Total PSB Writeoffs: INR 5.82 lakh crore (FY21 to FY25).

- Recovery Rate: Approximately 28 percent of written off amounts were recovered, meaning the public lender absorbed 72 percent of the loss.

- FY25 Writeoff: INR 91,260 crore (Provisional).

- Projected GNPA Rise: The RBI Financial Stability Report projected a rise in GNPA to 3 percent by March 2026 under baseline stress scenarios, indicating that fresh slippages are outpacing the cleanup.

Corporate Cronyism and the Public Deficit

The nexus between corporate borrowers and banking executives drives this phenomenon. By evergreening loans, corporate promoters retain control of their assets long after they have become insolvent. The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC), intended to be the cure, has seen its efficacy diluted by delays and low recovery values, prompting banks to prefer opaque restructuring loops over transparent resolution.

The result is a privatization of profits and a socialization of losses. When a PSB writes off a massive corporate loan, it depletes its capital base, which must eventually be replenished by taxpayer money or by eroding the value of public shareholders. The drop in headline bad loan numbers from over 9 percent in 2021 to under 3 percent in 2025 is not a victory of recovery but a testament to the scale of capital destruction accepted to sanitize the image of the banking sector.

As we move through 2026, the prohibition on AIF evergreening routes has forced banks to recognize some hidden stress. However, without strict penal action against the executives who authorized these circular flows, the culture of concealment persists, merely awaiting the next innovative loophole.

Boardroom Blindness: Governance Lapses and Complicit Auditors

The sanctuary of the boardroom, meant to be the first line of defense against financial malfeasance, has too often mutated into a theater of silence. Between 2020 and 2026, while the government and the Reserve Bank of India heralded a “clean banking” era, the internal machinery of oversight in Public Sector Banks (PSBs) frequently rusted from within. The narrative of declining bad loan ratios masks a darker reality: a systemic failure of governance where independent directors remained passive and statutory auditors acted as facilitators of fiction rather than guardians of truth.

The Optical Illusion of Asset Quality

Official data presents a comforting but misleading picture. By March 2025, the gross NPA ratio of PSBs had ostensibly dropped to near 2.5 percent, a significant fall from the crisis peaks of the previous decade. Yet, this improvement was not born solely from recoveries. It was engineered through massive write offs. From 2020 to 2025, PSBs erased over ₹5.82 lakh crore of bad loans from their balance sheets. In the financial year ending 2025 alone, banks wrote off ₹91,260 crore. These assets were technically removed to sanitize books, yet the borrowers often faced little practical consequence. The boardroom strategy was clear: manage the optics rather than fix the structural rot of credit underwriting.

The UCO Bank Debacle: A Case Study in Control Failure

Nothing illustrated the collapse of internal controls more starkly than the UCO Bank incident in November 2023. In a staggering lapse of digital governance, the bank credited ₹820 crore to various accounts due to an internal “technical glitch” involving the IMPS platform. For days, the board and management remained oblivious as erroneous credits flowed out. The Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) later launched raids across 67 locations, exposing how internal checks were bypassed. While the bank eventually recovered a portion of the funds, the incident shattered the myth that PSBs had modernized their risk management systems. It revealed a governance structure that was reactive, waiting for a disaster to strike before asking basic questions about digital security protocols.

The Silent Watchdogs: Auditor Complicity

The role of statutory auditors during this period shifted from negligence to active complicity. The National Financial Reporting Authority (NFRA), the audit regulator, issued a scathing circular in October 2024 flagging “gross negligence” in group audits. The regulator noted that principal auditors frequently relied on “fallacious interpretations” of auditing standards to ignore red flags in subsidiary companies.

The shadow of the ABG Shipyard fraud, which came to light in February 2022, loomed large over this period. It was India’s biggest bank fraud at ₹22,842 crore. Forensic audits later revealed that funds were diverted through 98 related entities. Yet, for years, statutory auditors signed off on the books. The NFRA and SEBI actions in 2024 and 2025 against audit firms highlighted a disturbing trend: auditors were often intimidated by management or comfortable with a “tickbox” approach. In 2025, the NFRA explicitly questioned why major audit firms failed to test related party transactions, the primary vehicle for corporate cronyism.

Regulatory Retribution

By 2025 and 2026, the patience of the regulator had worn thin. The RBI imposed a record number of penalties on cooperative and public banks for governance lapses. In July 2025, Union Bank of India faced regulatory censure for deficiencies in currency verification systems. More broadly, the RBI Annual Report released in 2025 noted a spike in enforcement actions, penalizing banks not just for financial breaches but for the “conduct of business” and lack of board oversight.

The crisis is no longer about unrecognized bad loans; it is about recognized collusion. When directors look away and auditors rubber stamp fraud, the bank ceases to be a financial intermediary and becomes a private coffer for the politically connected. Until the personal liability of board members is enforced with the same vigor as loan recovery, the cycle of crisis and recapitalization will continue.

Sectoral Stress: The Collapse of Infrastructure, Power, and Steel

The narrative of recovery in the Indian banking system often obscures a darker reality buried in the ledgers of Public Sector Banks. While headline gross non performing asset ratios improved between 2020 and 2026, this optical cleansing was largely achieved not through recovery, but through massive technical write offs. The rot in the core industrial sectors of infrastructure, power, and steel did not vanish; it was merely removed from the balance sheets to present a sanitized view of sovereign banking health.

The Great Write Off Illusion

Data presented to the Rajya Sabha in late 2025 reveals the scale of this financial engineering. Between the financial years 2020 and 2025, Public Sector Banks wrote off approximately ₹5.82 lakh crore (over USD 70 billion) in bad loans. This massive erasure of debt was most pronounced in the books of the State Bank of India, which alone extinguished over ₹80,197 crore from its loan book between 2022 and 2025. These were not small personal loans but substantial credit lines extended to corporate entities in the heavy industry sectors.

Infrastructure: The Silent Stagnation

Despite government claims of a capital expenditure boom, the infrastructure sector remains a graveyard of stalled capital. The Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MOSPI) released a damning report in early 2025 regarding central sector projects. As of December 2024, out of 1,820 monitored infrastructure projects, 431 projects reported cost overruns exceeding ₹4.82 lakh crore. Furthermore, 848 projects were delayed, with the average time overrun stretching to nearly 37 months.

The National Highways Authority of India (NHAI) saw a 15% dip in road widening execution in the 2024 to 2025 period compared to previous years. This slowdown signals a resurgence of stress in construction finance, where aggressive bidding by contractors in 2021 and 2022 clashed with rising input costs, leaving banks exposed to unfinished highways and bridges that generate no toll revenue.

Power Sector: The Green Paradox

The power sector presents a dual crisis of legacy debt and transition risk. While India celebrated reaching 510 GW of installed capacity by November 2025, with renewable energy constituting 51% of this total, the financial health of thermal power lenders deteriorated. The aggressive shift to renewables created a “stranding risk” for coal based power plants funded by state banks a decade ago. These plants now face lower Plant Load Factors, making them unable to service their original debts.

Although Distribution Companies (DISCOMs) posted a rare consolidated profit of ₹2,701 crore in FY25, this turnaround is fragile. The legacy dues owed to power generators remain high, forcing banks to continually restructure loans to the power sector under various “sustainable” framing mechanisms that essentially kick the can down the road.

Steel and the IBC Haircut

The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC), once touted as the ultimate solution to the NPA crisis, has turned into a mechanism for deep haircuts. In the steel and manufacturing sectors, which dominate the insolvency docket, creditors have taken severe losses. Data from the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India indicates that in the 2024 to 2025 fiscal period, the recovery rate for creditors slumped to approximately 32% of admitted claims. This means that for every ₹100 lent to these corporate entities, banks are recovering only ₹32, surrendering the rest to resolve the asset.

By September 2025, over 77% of ongoing insolvency cases had exceeded the mandatory 270 day resolution timeline. This delay erodes the value of the underlying steel and power assets, further reducing what banks can recover. The result is a cycle where corporate borrowers in these heavy industries effectively default, forcing banks to take a 68% loss, while the assets are sold cheap to new corporate owners, completing the cycle of wealth transfer.

This systematic cleanup suggests that the “NPA Crisis” was not solved but rather paid for by the public exchequer through recapitalization and the erosion of bank profits, effectively subsidizing the inefficiencies of the private infrastructure and industrial complex.

The Willful Defaulter: Distinguishing Intent from Market Failure

The distinction between a business collapse driven by external market forces and one engineered through malevolent intent constitutes the core of the bad loan crisis in India. While global economic downturns or sector specific crashes explain many Non Performing Assets, a significant subset belongs to a darker category: the willful defaulter. These are borrowers who possess the capacity to repay but refuse to do so, or worse, have siphoned off funds for purposes unrelated to the sanctioned business. Between 2020 and 2026, the data reveals a disturbing trend where corporate cronyism often masked theft as market failure.

The Rising Tide of Willful Defaults

Data released by the Reserve Bank of India paints a grim picture of this phenomenon. From March 2020 to March 2024, the number of willful defaulters rose significantly. By March 2024, a staggering 2,664 corporate borrowers were classified under this category, collectively owing the banking system approximately ₹1.96 lakh crore. This surge occurred despite the aggressive implementation of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code. The narrative often peddled by these entities involves blaming “policy paralysis” or “economic slowdowns” like the pandemic of 2020 and 2021. However, forensic audits frequently reveal a different story: the diversion of loans to offshore accounts or shell companies.

The following table highlights major entities flagged for willful default or fraud as of data available through 2025. These figures represent the vast sums of public money trapped in accounts where the intent to repay was arguably absent.

| Entity Name | Outstanding Amount (Approximate) | Sector |

|---|---|---|

| ABG Shipyard Ltd | ₹10,953 Crore | Shipbuilding |

| Gitanjali Gems Ltd | ₹8,516 Crore | Gems and Jewellery |

| Bhushan Power and Steel Ltd | ₹6,413 Crore | Steel |

| Rei Agro Ltd | ₹2,934 Crore | Agriculture |

| Winsome Diamonds | ₹2,931 Crore | Gems and Jewellery |

The Write Off Controversy

To maintain healthy balance sheets, Public Sector Banks often resort to “writing off” these bad loans. While the government maintains that a write off is merely a technical accounting shift and does not absolve the borrower of liability, the recovery rates tell a complicated story. Between the financial years 2020 and 2025, state owned banks wrote off an aggregate loan amount exceeding ₹6.15 lakh crore. In the financial year 2025 alone, major banks including the State Bank of India and Punjab National Bank collectively wrote off over ₹58,000 crore.

“A willful default happens when the borrower has not utilized the finance from the lender for the specific purpose for which finance was availed, and has diverted the funds for other purposes.” — Reserve Bank of India Definition.

Intent Versus Incompetence

The core issue remains the difficulty in legally proving intent. Corporate cronyism thrives in this gray area. Powerful promoters often leverage political connections to delay the classification of their accounts as fraud. By the time a forensic audit confirms the siphoning of funds, the assets have often been stripped or moved across borders. The case of Gitanjali Gems is emblematic; despite early red flags, the exposure grew until the inevitable collapse.

Recent trends for 2025 and 2026 indicate a new challenge: a sharp rise in reported bank frauds. Data from FY25 shows that while the gross NPA ratio has declined due to heavy write offs, the value of fraud cases has doubled to over ₹36,000 crore compared to the previous year. This suggests that while banks are cleaning up old legacy books, new forms of financial malfeasance are emerging, often buried under complex corporate structures designed to evade detection until it is too late. The willful defaulter remains the most potent symptom of a banking culture that occasionally struggles to separate bad luck from bad faith.

The Unmasking: The Central Bank’s Asset Quality Review (AQR)

The narrative of Indian banking between 2020 and 2026 is often sold as a triumph of recovery. By September 2025, the Gross Non Performing Assets (GNPA) ratio for Scheduled Commercial Banks had plummeted to a multi decade low of roughly 2.1 percent. Superficially, this suggests a sector restored to health, a vindication of the rigorous Asset Quality Review (AQR) initiated years prior. However, an investigative look beneath this pristine surface reveals a starker reality. The unmasking is not merely about identifying bad loans anymore; it is about exposing how they were made to disappear. The mechanism was not repayment but a massive, systemic exercise in writing off corporate debt.

The Math of Erasure

The sheer scale of capital destruction during this period is staggering. Government data presented in Parliament in August 2025 revealed that Public Sector Banks (PSBs) had written off bad loans totaling approximately ₹5.82 lakh crore over the preceding five financial years. If one expands the lens to the decade ending in 2025, the figure swells to an eye watering ₹16.35 lakh crore. While the AQR initially forced banks to acknowledge the rot, the subsequent strategy was to excise it from the balance sheets entirely to present a clean facade to investors.

In FY21 alone, amidst the economic tremors of the pandemic, banks wrote off ₹1.33 lakh crore. Even as the economy stabilized, the habit persisted. In FY24, banks removed another ₹1.70 lakh crore from their books. The official line maintains that a technical write off does not absolve the borrower of liability. Yet, the recovery data suggests otherwise. For every ₹100 written off, banks recovered only about ₹28 to ₹30. The remaining ₹70 was effectively a gift to the defaulter, absorbed by the bank and, by extension, the taxpayer who funded the repeated recapitalization of these institutions.

The insolvency Mirage and Corporate Cronyism

The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC), touted as the ultimate weapon against crony capitalism, increasingly functioned as a sanctuary for it. By late 2024 and early 2025, the recovery rate for creditors in IBC cases had stagnated near 30 percent. This implies that operational and financial creditors were taking “haircuts” of roughly 70 percent on average. In numerous high profile cases involving large corporate houses, the haircut exceeded 90 percent.

This dynamic created a perverse incentive structure. Large corporate borrowers could default, drag the process through the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT) for years, and eventually see their assets sold back to a friendly bidder or a new owner for a fraction of the cost, leaving the public sector banks to swallow the loss. The “cronyism” here is structural: the system prioritized cleaning the bank books over recovering public money. The swift exit of defaulting promoters, often with their personal wealth intact, stood in sharp contrast to the aggressive recovery tactics deployed against small farmers and middle class borrowers.

A Clean Balance Sheet, A Dirty Truth

By 2026, the Indian banking sector boasted robust capital buffers and a pristine GNPA ratio of under 2 percent. But this stability was purchased at an exorbitant price. The reduction in bad loans was driven primarily by write offs, not by the revival of stalled projects or the repayment of dues. The AQR began as a quest for truth, demanding that banks label a spade a spade. It ended with banks burying the spade altogether.

The legacy of this era is not just the cleaned ledgers but the establishment of a moral hazard where massive corporate default is treated as a routine cost of doing business, subsidized by the sovereign. The unmasking is complete: the crisis was resolved not by fixing the behavior of the borrower, but by adjusting the accounting of the lender.

Capital Erosion: The Impact on Bank Balance Sheets and Profitability

The narrative of the Indian banking sector from 2020 to 2026 is often presented as a triumphant turnaround story. Public Sector Banks (PSBs), once bleeding from the wounds of bad loans, are now posting record profits. In the fiscal year 2024 to 2025 alone, PSBs reported a cumulative net profit of nearly ₹1.78 lakh crore. However, an investigative look beneath the surface reveals a disturbing reality: this profitability has come at the cost of massive capital erosion, driven by aggressive technical write offs and deep haircuts on corporate debt that favor politically connected conglomerates.

The Provisioning Paradox

The primary mechanism for this capital erosion is provisioning. When a loan turns bad, or becomes a Non Performing Asset (NPA), the bank must set aside capital to cover the potential loss. This money comes directly from the bank’s operating income, effectively eating into what could have been shareholder dividends or capital for new lending.

From 2020 to 2026, the Provisioning Coverage Ratio (PCR) of state owned banks surged, with many lenders like Indian Overseas Bank and Canara Bank reporting PCR levels exceeding 93 percent by late 2025. While regulators applaud this as “balance sheet resilience,” it essentially means that for every ₹100 of bad debt, the bank has already assumed a loss of ₹93. This is capital that has vanished from the financial system. The record profits of 2024 and 2025 were only possible because the bulk of this provisioning pain was absorbed in previous years, often supported by taxpayer funded recapitalization.

The Write Off Machine

The most alarming trend is the sheer magnitude of loans removed from the books entirely. Between 2020 and 2025, Public Sector Banks wrote off approximately ₹6.15 lakh crore in bad loans. In the fiscal year 2024 to 2025 alone, PSBs wrote off over ₹91,000 crore. Banks argue that these are “technical write offs” and recovery efforts continue. However, the recovery rate paints a bleak picture.

Data from the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) indicates that recovery rates for written off accounts hover between 15 percent and 20 percent. This implies that roughly 80 percent of the capital allocated to these corporate loans is permanently lost. The balance sheets look clean today not because the money was returned, but because the debts were erased using the bank’s own capital buffers.

Corporate Haircuts and Cronyism

The erosion of capital is most evident in the resolution process under the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC). While the IBC was designed to maximize asset value, it has frequently facilitated the transfer of valuable assets to large corporate houses at steep discounts, leaving banks to absorb the difference.

A striking example from late 2024 involved the acquisition of ten distressed companies by entities linked to the Adani Group. Banks were forced to settle claims totaling approximately ₹62,000 crore for a mere ₹16,000 crore. This represented a “haircut” of 74 percent. In specific cases, such as the resolution of HDIL (Project BKC), the haircut suffered by lenders reached as high as 96 percent. These deep discounts represent a direct transfer of wealth from public institutions to private oligarchs, with the loss crystalized on the PSB balance sheet.

The Illusion of Health

By September 2025, the Gross NPA ratio of PSBs had fallen to a multi decade low of 2.1 percent. Yet, this metric is misleading without considering the denominator effect. The reduction is largely driven by the numerator (bad loans) being written off, not recovered. Meanwhile, the capital base required to absorb these shocks was not generated through organic banking operations but was bolstered by government injections.

The long term impact is a banking sector that is risk averse and capital constrained despite high headline profits. The Return on Assets (RoA) has improved, crossing 1 percent in 2025, but this efficiency is fragile. If the aggressively written off loans from the 2020 to 2024 cycle are never recovered, the capital erosion is permanent. The taxpayer has effectively bailed out corporate defaulters, cleaning the slate for banks to restart the lending cycle, potentially to the same beneficiaries.

The Bailout Burden: Recapitalization Using Taxpayer Money

The narrative of the Indian banking sector in 2026 is one of apparent triumph. Headlines celebrate record profits and robust balance sheets for Public Sector Banks (PSBs). Yet, scratching beneath this glossy surface reveals a financial architecture rebuilt on the ruins of taxpayer money. The journey from the crisis years of 2020 to the stability of 2026 was not a miracle of efficiency but a massive, state sponsored cleanup operation where the public bore the cost of private failure.

At the heart of this issue lies the mechanism of recapitalization. Between 2016 and 2021, the central government infused over ₹3.10 lakh crore into state run banks. This injection was necessary because these institutions had lent recklessly to politically connected corporate groups during the “boom” years, leading to a mountain of bad loans. When these corporate giants defaulted, the banks faced collapse. Instead of allowing market forces to punish this incompetence, the government stepped in with a sovereign guarantee, effectively converting corporate debt into public burden.

The Invisible Cost of Write Offs

While direct recapitalization grabs headlines, the silent killer of public wealth is the “write off.” This accounting practice allows banks to remove bad loans from their active balance sheets, making their financial health look better than it is. Real data from the Ministry of Finance reveals a staggering trend. From the financial year 2020 to 2025, Public Sector Banks wrote off approximately ₹5.82 lakh crore in bad loans. To put this into perspective, this sum could have funded the entire national health budget for multiple years.

Bankers argue that a write off does not mean a waiver and that recovery efforts continue. However, the numbers tell a different story. Of the ₹5.82 lakh crore removed from the books between 2021 and 2025, banks recovered only about ₹1.65 lakh crore. This means less than 28% of the public money erased from the ledgers ever came back. The remaining 72% represents a direct transfer of wealth from the common taxpayer to defaulting corporate entities.

Corporate Cronyism and the Haircut Culture

The beneficiaries of this largesse are rarely small farmers or student borrowers. Data indicates that large industries and services accounted for nearly 56% of total write offs. The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC), touted as the ultimate solution for debt recovery, often results in massive “haircuts” for lenders. In several high profile cases resolved between 2023 and 2025, banks accepted recoveries as low as 30% to 35% of the admitted claims. The remaining debt was vaporized, leaving the bank to fill the hole with capital provided by the government or raised from small depositors.

The Bad Bank Experiment

In 2021, the government incorporated the National Asset Reconstruction Company Limited (NARCL), popularly known as the “Bad Bank,” to aggregate and resolve these stressed assets. The goal was ambitious: acquire ₹2 trillion in bad loans by 2026. However, the performance has been sluggish. By October 2025, recovery from these acquired assets hovered around ₹4,192 crore, a mere fraction of the acquisition cost. The structural dualism between NARCL and the India Debt Resolution Company Limited (IDRCL) created operational friction, further delaying the return of public funds.

Key Statistics (2020 to 2026):

- Total Write Offs (FY21 to FY25): ₹5.82 lakh crore

- Recovery Rate on Written Off Accounts: Approximately 28%

- Corporate Share of Write Offs: ~56%

- Direct Government Infusion (2016 to 2021): ₹3.10 lakh crore

- Bad Bank Recovery (Oct 2025): ₹4,192 crore

The Illusion of Profitability

By 2026, the government ceased major capital infusions, pointing to the banks’ ability to raise ₹24.86 lakh crore from the markets over the previous decade. PSBs even paid a dividend of ₹34,990 crore in FY25. However, this profitability is built on a foundation of “technical write offs” that cleansed the books at a colossal historical cost. The banks are profitable today because the taxpayer absorbed the losses of yesterday.

This cycle creates a moral hazard where corporate borrowers know that in the event of failure, the state will cushion the fall for the lender. The “Bailout Burden” is not just a fiscal statistic; it is a testament to a system where profits are privatized for the elite, while losses are socialized for the masses.

The Unending Chase: A 2026 Status Report

The flight of high profile borrowers from India has long symbolized the systemic vulnerabilities within the Public Sector Bank (PSB) network. Between 2020 and 2026, the narrative shifted from shock to a grinding legal war of attrition. While the Fugitive Economic Offenders Act (FEOA) of 2018 provided a statutory framework to confiscate assets, the practical enforcement has faced resistance through complex international legal loopholes. As of late 2025, the Ministry of Finance reported that 15 designated fugitive offenders collectively owed Public Sector Banks over 58,000 crore rupees, with barely one third of that amount recovered.

The London Deadlock: Mallya and Modi

The case of Vijay Mallya remains the most glaring example of legal stasis. Despite the UK High Court clearing his extradition in 2020, he remains in London as of early 2026. The delay is attributed to a “confidential legal process,” widely understood to be an asylum claim, which prevents the UK Home Office from signing the extradition order. While banks have recovered approximately 14,000 crore rupees through the liquidation of his seized domestic assets, the principal debt continues to accrue interest, leaving a significant deficit.

Nirav Modi, currently lodged in Thameside and Pentonville prisons, has faced a more turbulent confinement. His legal defense has pivoted to human rights arguments, citing suicide risk and poor prison conditions in India. In December 2025, a UK court adjourned his appeal reopening to March 2026, demanding “chunky assurances” from India regarding his medical care at Arthur Road Jail. Unlike Mallya, the recovery rate from Modi remains abysmal, standing at a mere 7 percent of the principal owed as of late 2025.

The Island Hoppers: Choksi and the Sandesaras

The saga of Mehul Choksi took a dramatic turn in the 2023 to 2025 period. After the removal of the Interpol Red Corner Notice in 2023, Choksi regained freedom of travel, arguing that his 2021 disappearance in Dominica was a state sponsored abduction. However, this freedom was curtailed in April 2025 when he was detained in Belgium, reigniting extradition hopes for Indian agencies.

Perhaps the most successful evasion strategy belongs to the Sandesara brothers of Sterling Biotech. Nitin and Chetan Sandesara have leveraged jurisdiction hopping to great effect. Reports from 2023 confirmed their operations in Nigeria, where they became key players in the local oil sector. By acquiring Albanian passports and citizenship, they effectively insulated themselves from Indian warrants. In November 2025, the Supreme Court of India cleared a settlement path requiring them to pay 570 million dollars, acknowledging the difficulty of physical extradition from territories with weak legal treaties.

- Total Outstanding Dues: ₹58,082 Crore

- Total Recovered Amount: ₹19,187 Crore

- Recovery Rate: ~33%

- Major Defaulters: Vijay Mallya (₹22,000+ Cr), Nirav Modi (₹9,000+ Cr), Sandesara Group (₹15,000+ Cr).

Systemic Loopholes and Human Rights Pleas

The pattern across these cases reveals a standardized playbook for evasion. Offenders utilize the “Golden Visa” programs of nations like Antigua or Albania to secure alternative citizenship. Once abroad, they exploit the stringent human rights laws of Western nations. The confidentiality of asylum proceedings in the UK acts as an effective indefinite stay on extradition. furthermore, the definition of “cruel and degrading treatment” in European courts has forced Indian authorities to upgrade prison facilities solely to meet foreign judicial standards.

While the Enforcement Directorate has been successful in attaching domestic assets, the cross border seizure of funds remains challenging. The 2020 to 2026 period highlights that while the FEOA creates a deterrent, the global legal infrastructure still favors the fugitive who has the resources to litigate indefinitely.

Quid Pro Quo: Investigating Bribery and Kickbacks in Loan Sanctions

By February 2026, the official narrative surrounding Indian Public Sector Banks (PSBs) had shifted to one of triumphant recovery. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) released data in its Financial Stability Report showing that Gross Non Performing Assets (NPAs) had plummeted to a multi decade low of 2.58% by March 2025. On the surface, the books were clean. The balance sheets were repaired. Yet, beneath this veneer of financial health lies a persistent, festering culture of “quid pro quo” that continues to rot the core of state owned lending institutions.

While the headlines celebrate recovery rates, the handcuffs tell a different story. The period from 2020 to 2026 has not just been about cleaning up bad loans; it has been a continuous saga of unmasking the bribery mechanisms that created them. The definition of creditworthiness in many corridors of power remains contingent not on collateral or cash flow, but on the kickback.

The Anatomy of the Kickback: The BECIL Case

The sophisticated evolution of bribery was laid bare in April 2025, when the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) arrested a former General Manager of Broadcast Engineering Consultants India Limited (BECIL), a public sector enterprise. The investigation revealed a classic quid pro quo arrangement involving a ₹50 crore loan disbursement.

Investigators found that the loan was not merely a business transaction but a vehicle for graft. A bribe of ₹3 crore was allegedly exchanged to facilitate the release of funds to a private entity, The Green Billions Limited. This was not a case of a loan going bad due to market forces. It was a purchase of capital. The officials involved allegedly bypassed standard operating procedures and security requirements, essentially selling the loan sanction in exchange for personal enrichment. This case exemplifies the modern mechanism of bank fraud: the kickback is the primary product; the loan is merely the delivery system.

The Ghosts of Mega Frauds: ABG Shipyard and DHFL

While new scams surface, the legal system is still grappling with the debris of the colossal frauds that defined the early 2020s. In August 2025, a Rouse Avenue court in Delhi finally took cognizance of the charge sheet in the ABG Shipyard case, termed the “biggest bank fraud” in Indian history. The numbers are staggering: ₹22,842 crore siphoned off from a consortium of 28 banks led by ICICI and IDBI, but heavily impacting state owned giants like SBI.

The forensic trail revealed that funds were not lost but diverted. Money meant for ship building was routed through 98 related companies to Singapore and other tax havens. The quid pro quo here was systemic. Bank officials at various levels ignored early warning signals, known as “red flags,” for years. The delay in classifying the account as fraud allowed the promoters to strip the company of assets.

Similarly, the Dewan Housing Finance Corporation Ltd (DHFL) saga reached a critical juncture in August 2025 when the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT) declared former promoter Kapil Wadhawan bankrupt. The Wadhawan brothers were accused of defrauding a consortium of 17 banks, led by the Union Bank of India, of over ₹34,000 crore. The investigation highlighted a web of “shell companies” and “fake borrowers” used to route public money back to the promoters. The quid pro quo extended to the very top of the banking ecosystem, implicating leaders who accepted kickbacks in exchange for buying dubious debentures.

The Cost of Corruption (2020 to 2026)

₹22,842 Crore: The value of the ABG Shipyard fraud, where funds were diverted to offshore entities.

₹34,615 Crore: The outstanding amount in the DHFL scam affecting a Union Bank led consortium.

2.58%: The Gross NPA ratio of PSBs in March 2025, a figure achieved largely through massive technical write offs rather than full cash recovery.

The Retail Bribe: Corruption at the Branch Level

The rot is not limited to corporate boardrooms. It trickles down to the branch manager’s desk, affecting small businesses and farmers. In December 2024, the CBI arrested a Branch Manager of the Bank of Baroda in Shikarpur, Uttar Pradesh. The demand? A ₹1 lakh bribe to sanction a loan of ₹80 lakh. The manager was caught red handed, accepting the illicit payment via a signed cheque.

Months later, in January 2026, a similar pattern emerged in an investigation involving a Gramin Bank in Uttar Pradesh, where officials demanded a cut of the loan amount before disbursement. These “micro kickbacks” destroy the integrity of the banking system at the grassroots level. They turn a public service into a private auction, where capital is available only to those willing to pay the gatekeeper’s toll.

The Clean Up Illusion

The drastic reduction in NPAs by 2026 is a statistical success but a moral failure. Much of the “cleaning” has been achieved through provisioning and write offs, effectively shifting the cost of these bribes from the bank’s ledger to the taxpayer’s pocket. The recovery rate, though improved to 26.2% in FY25, still means that for every rupee lent in these corrupt deals, the public recovers barely a quarter.

The investigations of 2025 and 2026 prove that the quid pro quo culture is resilient. As long as loan sanctions remain a discretionary power subject to private negotiation rather than algorithmic transparency, the cycle of bribery, bad loans, and taxpayer bailouts will continue. The faces change, from the Wadhawans to local managers, but the transaction remains the same: cash for credit.

The Watchdog’s Sleep: Regulatory Oversights and Delayed Interventions

The role of a central bank is often likened to that of a shepherd guarding the flock, yet the period from 2020 to 2026 reveals instances where the shepherd appeared to slumber while wolves ravaged the fold. In the context of the Indian banking sector, specifically regarding Public Sector Banks or PSBs, the Reserve Bank of India faced mounting criticism for its reactive rather than proactive stance. While the government celebrated improved balance sheets and record profits in 2024 and 2025, a deeper investigative analysis suggests this stability was manufactured through massive technical erasures of debt and delayed regulatory crackdowns on questionable lending practices.

The most glaring evidence of regulatory leniency lies in the handling of bad loans. Between the fiscal years of 2021 and 2025, Public Sector Banks erased over Rs 5.82 lakh crore from their books. These technical deletions, often termed “write offs” in banking parlance, allow banks to remove stalled assets from their balance sheets, artificially lowering their reported bad loan ratios. The State Bank of India, the largest lender in the nation, led this charge. In the fiscal year 2025 alone, SBI erased Rs 20,309 crore of bad debt. While the Finance Ministry argues these loans are still recoverable, the data paints a grim picture. Recovery rates for these erased accounts hover pitifully low, often between 14 percent and 28 percent. The regulator allowed this massive cleanup exercise to continue without mandating stricter accountability for the executives who authorized the initial bad loans. Consequently, the taxpayer indirectly absorbs the loss while bank balance sheets appear pristine.

Beyond the erasure of debt, the regulatory apparatus failed to spot systemic manipulation until it had already metastasized. A prime example is the “evergreening” of loans through Alternative Investment Funds or AIFs. For years, banks utilized a loophole where they would invest in an AIF, which would then lend that same money back to a distressed borrower of the bank. This circular flow of funds allowed the borrower to repay the original bank loan, preventing it from being classified as a default. It was a sophisticated shell game designed to hide the rot. The Reserve Bank of India finally issued a circular prohibiting this practice on December 19, 2023. By then, however, countless billions had already been funneled through this route, obscuring the true extent of corporate stress. The intervention was necessary but arrived years too late, effectively granting banks a long amnesty period to mask their failures.

When the regulator did act, the punitive measures often resembled a gentle tap on the wrist rather than a deterrent. In January 2025, the central bank imposed a penalty of Rs 1.63 crore on Canara Bank for failing to comply with norms regarding priority sector lending and interest rates. Similarly, the State Bank of India faced a penalty of Rs 2 crore in 2024 for regulatory breaches. To a bank that generates profits in the tens of thousands of crores, a penalty of two crore rupees is statistically insignificant. It is merely a cost of doing business. These meager fines fail to enforce discipline. In contrast, the fraud losses reported by Public Sector Banks in the fiscal year 2025 surged to Rs 25,667 crore, accounting for over 71 percent of the total fraud in the banking system. The divergence between the colossal value of fraud and the minuscule value of penalties exposes a broken disciplinary framework.

Furthermore, audits frequently discovered “divergence” where banks underreported their bad loans to present a healthier image. City Union Bank, though a private entity, was fined Rs 66 lakh for such discrepancies, a symptom of a wider industry malady. Public Sector Banks also faced scrutiny for similar obfuscations. The delay in recognizing these divergences meant that corrective action plans were postponed, allowing the financial health of the institutions to deteriorate further before any medicine was administered.

The narrative of the Indian banking sector from 2020 to 2026 is one of optical recovery. The regulatory body allowed banks to prioritize the optics of financial health over the substance of prudent lending. By permitting vast debt erasures without high recovery rates and delaying the crackdown on complex structures like AIFs, the watchdog allowed the creation of a system where corporate cronyism could thrive in the shadows. The cost of this regulatory sleep is not paid by the bankers who receive bonuses for clean books, but by the public who must ultimately capitalize these institutions when the hidden rot eventually causes the foundation to crack.

The IBC Paradigm: Introduction of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code

The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, enacted in 2016, arrived with the promise of a structural shift in Indian finance. It sought to replace the era of “debtor in control” with “creditor in control.” For decades, corporate borrowers treated bank loans as personal fiefdoms, often defaulting with impunity while retaining management rights. The IBC aimed to change this dynamic by instating a time bound resolution process. However, an analysis of data from 2020 to 2026 reveals a complex reality where the initial optimism has collided with systemic delays, massive haircuts, and persistent corporate cronyism.

The Delay Dilemma: 2020 to 2026

Speed was the primary selling point of the IBC. The law originally mandated a 330 day limit for the completion of the Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process (CIRP). Yet, reality has drifted far from this statutory ideal. Data from the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India (IBBI) shows a steady deterioration in timeline adherence. By late 2025, the average time taken to close a CIRP had climbed to 724 days, more than double the legal limit. This was a sharp increase from 550 days recorded in 2022.

These delays are not merely administrative statistics; they represent value destruction. As proceedings drag on through litigation in the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT), the underlying assets of the debtor deteriorate. Machinery rusts, contracts expire, and employees leave. For Public Sector Banks, this delay translates into prolonged provisioning periods where capital remains locked without generating returns. The promise of swift exit for lenders has largely morphed into a long wait in legal corridors.

Haircuts and Recovery Rates

The term “haircut” became a defining feature of the banking lexicon during this period. While the IBC succeeded in stripping defaulting promoters of their companies, the financial recovery for banks has been modest. By September 2025, creditors were taking an average haircut of approximately 67% on their admitted claims. This means for every 100 rupees lent, banks were recovering only 33 rupees.

The recovery rate remained stagnant around 32% to 33% throughout the 2024 and 2025 fiscal years. In some notable cases involving massive conglomerates, recoveries dipped even lower, raising questions about asset valuation. The disparity between the liquidation value and the fair value often allowed bidders to acquire assets at rock bottom prices. Public Sector Banks, often the lead lenders in these consortiums, bore the brunt of these write offs, effectively transferring public wealth to private buyers at discounted rates.

Liquidation over Resolution

The ultimate goal of the IBC was to save viable companies, not destroy them. However, the data points to a skew towards liquidation. By September 2024, liquidation orders had significantly outpaced approved resolution plans, with 2630 orders for liquidation against just 1068 resolution plans. This trend suggests that for many stressed assets, the market found no value in revival, or the process itself made revival unviable.

While the ratio of resolution to liquidation showed slight improvement in the final quarter of the 2025 fiscal year, reaching 91%, the cumulative data indicates that the IBC often functions as a graveyard rather than a hospital for corporate entities. This tendency towards liquidation further depresses recovery rates, as liquidation value is typically the lowest tier of asset valuation.

The NARCL Factor and Future Outlook

To address the backlog of legacy bad loans, the government operationalized the National Asset Reconstruction Company Ltd (NARCL), often called the bad bank. By the 2026 fiscal year, NARCL targeted acquiring 2 trillion rupees in stressed assets. As of October 2025, it had managed recoveries totaling 4192 crore rupees, representing about 13% of its acquisition cost. While this entity was designed to aggregate debt and clear bank balance sheets, it too faces the hurdle of finding buyers in a market wary of litigation and hidden liabilities.

The introduction of the IBC Amendment Bill 2025 sought to plug these gaps by enforcing stricter timelines and introducing the “clean slate” principle to protect buyers from past claims. Yet, the interplay between aggressive corporate legal strategies and an overburdened judiciary continues to hamper the efficiency of the code. For the public sector lender, the IBC remains a necessary but blunt instrument, one that has ended the impunity of defaulters but has yet to deliver the full economic recovery originally envisioned.

Mega Mergers: Consolidating PSBs to Absorb Financial Shock

The dawn of April 1, 2020, marked a seismic shift in the Indian banking landscape. The amalgamation of ten public sector banks into four anchor banks was not merely an administrative resizing but a strategic maneuver to insulate the financial system from a looming collapse. By absorbing weaker lenders like Oriental Bank of Commerce and United Bank of India into Punjab National Bank, or Syndicate Bank into Canara Bank, the government aimed to create entities with balance sheets large enough to absorb the shock of toxic loans. Yet, an investigation into the data from 2020 to 2026 reveals that while these mega mergers created size, they also served to obfuscate the true cost of corporate cronyism through massive write offs and deep haircuts.

Key Financial Indicators (2020 to 2026)

- Merger Event: Consolidation of 10 PSBs into 4 (April 2020).

- Total Write offs (FY16 to FY25): Over Rs 12.08 lakh crore.

- FY25 PSB Net Profit: Rs 1.91 lakh crore (Record High).

- Average NCLT Haircut (2025): Approximately 67 percent.

- GNPA Ratio (Sept 2025): 2.1 percent (Multi decade low).

The Illusion of Profitability

By the financial year ending March 2025, the narrative appeared triumphant. Public Sector Banks reported a collective net profit of Rs 1.91 lakh crore, a staggering turnaround from the collective net loss of Rs 1,629 crore in FY20. Headlines celebrated the gross Non Performing Assets ratio falling to a historic low of 2.1 percent by September 2025. However, this glossy surface hides a darker reality of how these balance sheets were cleaned.

The reduction in bad loans was not primarily driven by recovering money from defaulting corporate borrowers. Instead, it was achieved through aggressive write offs. Between 2015 and 2025, state owned banks wrote off over Rs 12 lakh crore. In FY25 alone, State Bank of India removed Rs 20,309 crore from its books, while Punjab National Bank wrote off Rs 12,159 crore. These loans, primarily owed by large corporate houses, were removed from the asset column to reduce the NPA ratio, effectively utilizing public capital to absorb private default.

The Haircut Reality

The insolvency resolution process, touted as the remedy for crony capitalism, has evolved into a mechanism for legitimizing massive losses. Data from the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India reveals that by late 2025, financial creditors were taking an average haircut of 67 percent on admitted claims. In simpler terms, for every Rs 100 owed by a defaulting corporation, the banks recovered only Rs 33. The remaining Rs 67 was sacrificed.

This trend points to a systemic transfer of wealth. The mega mergers provided the necessary capital buffer to absorb these haircuts without triggering immediate bank failures. For instance, the combined entity of Union Bank, Andhra Bank, and Corporation Bank could withstand provisions that would have sunk the smaller banks individually. The consolidation allowed the state to mask the insolvency of smaller lenders by merging them with stronger ones, thereby diluting the visibility of the crisis while the underlying assets continued to rot.

Structural Weakness Disguised as Strength