The Taiwan Silicon Semiconductor Shield: Defense Strategy Risks Versus Strategic Realities

Why it matters:

- The traditional "Taiwan Silicon Semiconductor Shield" is no longer effective in deterring Chinese aggression.

- A shift in U.S. policy towards onshoring semiconductor production marks a significant departure from traditional deterrence strategies.

The “Taiwan Silicon Semiconductor Shield”, the long-held geopolitical axiom that Taiwan’s dominance in advanced semiconductor manufacturing guarantees U. S. military intervention and deters Chinese aggression, has fractured under the weight of 2025’s strategic realities. For decades, the theory rested on a premise of indispensability: as long as Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) produced the world’s most serious logic chips, the global economy could not afford a conflict. By late 2025, yet, this shield has eroded into a “Silicon Paradox,” where the very assets meant to ensure safety have become primary for capture, sabotage, or blockade.

The shift in U. S. policy rhetoric marks the most significant departure from traditional deterrence. In a September 2025 interview, U. S. Secretary of Commerce Howard Lutnick explicitly dismantled the “indispensability” argument, calling for a “50-50” production split between the U. S. and Taiwan. This pivot signals a transition from a strategy of “protecting Taiwan to save the chips” to “onshoring chips to survive Taiwan’s loss.” The operationalization of this policy is clear in the accelerated volume production of TSMC’s 2nm node in Arizona, projected to reach serious mass by 2026, diluting the “hostage” value of the Hsinchu and Kaohsiung fabs.

The “Broken Nest” and Scorched Earth

Strategic discourse in 2024 and 2025 has been dominated by the controversial “Broken Nest” deterrence concept, originally articulated in a U. S. Army War College paper. The theory suggests that to deter invasion, Taiwan must credibly threaten to self-destruct its semiconductor infrastructure, a “scorched earth” policy to ensure Beijing captures nothing ruins. While Taiwanese Defense Minister Chiu Kuo-cheng publicly rejected this method in mid-2024, stating the military would “not tolerate” U. S. destruction of domestic assets, the strategic ambiguity remains. Reports from late 2025 indicate that U. S. contingency planning includes specific for the emergency evacuation of key TSMC personnel and the remote disabling of Extreme Ultraviolet (EUV) lithography machines, rendering the fabs useless without physical demolition.

| Strategic Actor | Primary Objective | Operational Stance (2025) | Key Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States | Supply Chain Resilience | “50-50” Production Split; Onshoring 2nm/3nm capacity | Arizona Fab 21 volume ramp-up |

| China (PRC) | Sanction Proofing / Autarky | 35% Equipment Self-Sufficiency; “Cold Start” Blockade Drills | Domestic 7nm yield stabilization |

| Taiwan (ROC) | “Silicon Shield” Deterrence | Retaining 90%+ of advanced node R&D; “Porcupine” Defense | 2nm mass production in Kaohsiung |

China’s “Justice Mission-2025” and the Blockade Reality

Beijing’s military calculus has evolved from invasion scenarios to strangulation strategies, specifically targeting the energy inputs required to run Taiwan’s fabs. The “Justice Mission-2025” exercises, conducted by the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) in December 2025, featured a “cold start” blockade simulation with zero warning. Unlike previous drills, these exercises focused on the ports of Kaohsiung and Keelung, specifically targeting Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) terminals.

Data from the Taiwan Ministry of Economic Affairs reveals a serious vulnerability: as of Q4 2025, Taiwan’s LNG reserves stand at just 11 to 14 days of supply. Semiconductor fabrication is energy-intensive; a disruption in stable power supply for even milliseconds can scrap months of wafer production. The PLA’s strategy suggests a belief that a kinetic invasion is unnecessary if a blockade can starve the fabs of power, forcing an economic capitulation before the U. S. can mobilize a carrier strike group. The 35% surge in China’s domestic semiconductor equipment self-sufficiency in 2025 further emboldens this method, as Beijing reduces its own reliance on imported tools, so lowering the self-inflicted economic damage of a Taiwan Strait emergency.

The Economic Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD)

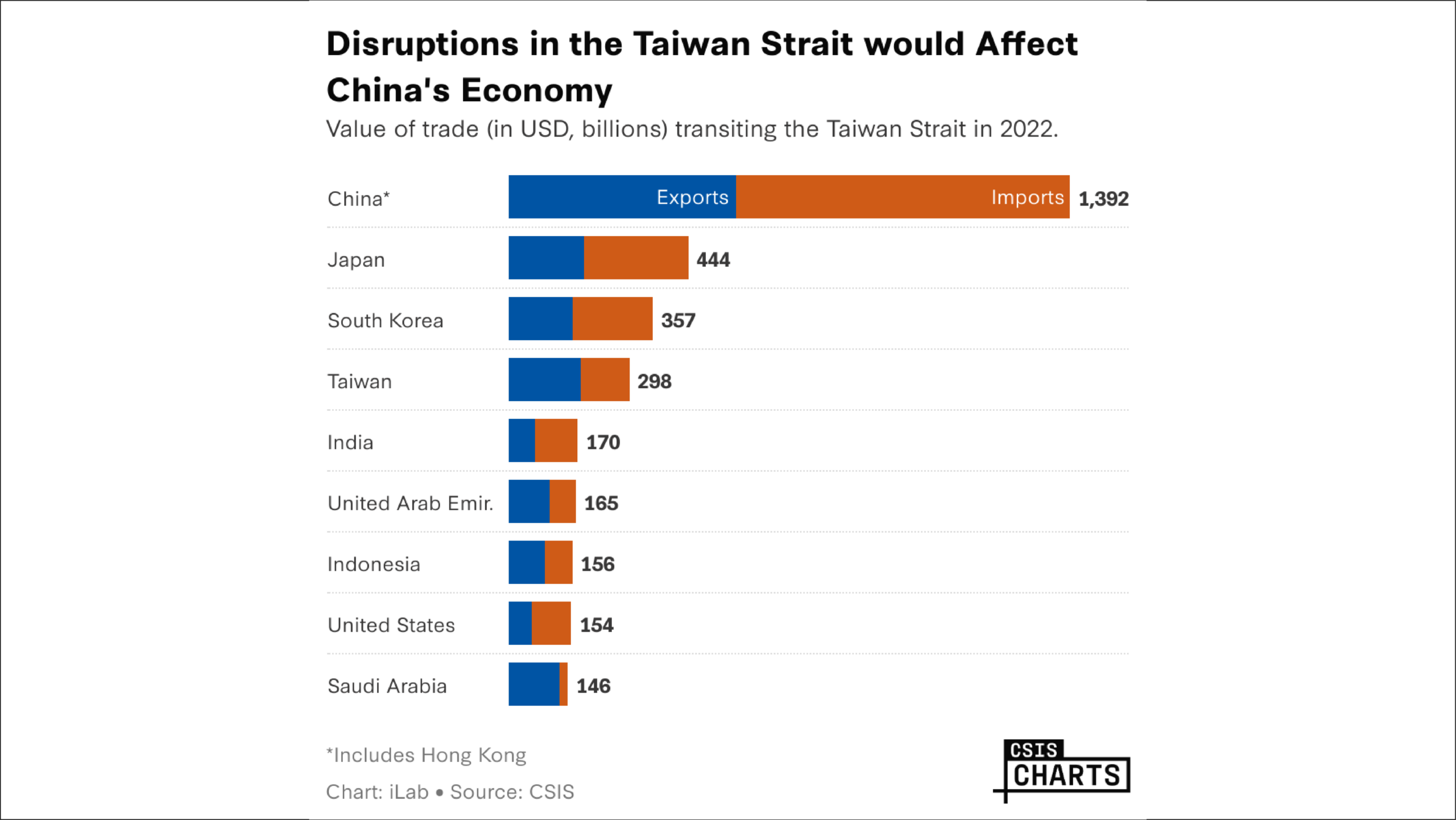

even with the of the shield, the economic remain catastrophic. Verified trade data estimates that a blockade of the Taiwan Strait would disrupt approximately $2. 45 trillion in global trade activity. Taiwan’s GDP, which surged by 8. 6% in 2025 driven by the AI hardware boom, is dangerously over-leveraged on a single sector. TSMC’s dominance is absolute, holding a 72% global foundry market share in Q3 2025 and generating 74% of its revenue from advanced nodes (7nm and ).

“The assumption that economic interdependence prevents war is a fallacy. In 2025, we see Beijing pricing in the economic shock of a semiconductor blockade as a necessary cost of sovereignty, while Washington prices in the loss of Taiwan as a manageable supply chain disruption.”

This creates a dangerous window of vulnerability. If Beijing believes the U. S. is successfully insulating itself via the CHIPS Act and international diversification, the incentive to act before that insulation is complete increases. The “Silicon Shield” is no longer a static defense; it is a decaying asset, and the race to its strategic relevance is accelerating on both sides of the Pacific.

TSMC Market Dominance: Quantifying the 92 Percent Advanced Node Monopoly

The strategic vulnerability of the United States is not defined by the total volume of semiconductors produced globally, by a singular, choke-point statistic: as of late 2025, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) controls 92 percent of the world’s leading-edge logic chip manufacturing capacity. While legacy nodes (28nm and above) see distributed production across China, the U. S., and Europe, the sub-7nm process nodes essential for artificial intelligence, hypersonic guidance systems, and fighter jets are a TSMC monopoly. This concentration has transformed the “Silicon Shield” from a deterrent into a single point of failure for the entire Western defense industrial base.

Data from the fourth quarter of 2025 indicates that TSMC’s dominance has accelerated rather than plateaued. In the 3nm process node, the serious threshold for Nvidia’s Blackwell AI accelerators and Apple’s M-series silicon, TSMC commands a 90 percent market share. Competitors have failed to provide a viable alternative. Samsung Foundry, the only other entity attempting mass production at 3nm, reported yields near 50 percent throughout 2025, rendering their output commercially unviable for high-volume clients like Qualcomm and Google. Consequently, Google shifted its Tensor G5 production entirely to TSMC, further cementing the Taiwanese foundry’s stranglehold on the sector.

The financial illustrates the of this monopoly. In Q3 2025 alone, TSMC posted revenue of $33. 1 billion, capturing 71 percent of the total global foundry market revenue. This figure dwarfs Samsung’s foundry division, which saw its market share contract to just 6. 8 percent in the same period. Intel, even with its “IDM 2. 0” strategy and massive subsidies under the CHIPS Act, has yet to secure significant external volume for its 18A node, leaving the U. S. without a domestic fail-safe for new fabrication. The gap is not closing; it is widening, with TSMC’s advanced node capacity (sub-7nm) projected to grow by another 69 percent by 2028.

The Yield Gap: Why Competitors Cannot Catch Up

The barrier to entry for advanced manufacturing is no longer just capital expenditure; it is process mastery. TSMC’s transition to the 2nm node, scheduled for volume production in late 2025, is built on a foundation of consistently high yields that competitors cannot replicate. Industry analysis confirms that TSMC achieves yields exceeding 80 percent on its mature 3nm FinFET lines, while Samsung’s Gate-All-Around (GAA) architecture struggles with defect densities that make large-die manufacturing prohibitively expensive.

| Foundry | Global Market Share (Q3 2025) | Advanced Node Share (<7nm) | Est. 3nm Yield Rate | Key Advanced Clients |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TSMC | 71. 0% | ~92% | >80% | Apple, Nvidia, AMD, Qualcomm |

| Samsung | 6. 8% | ~8% | ~50% | Internal (Exynos), Limited External |

| SMIC | 5. 1% | 0% (Sanctioned) | N/A | Huawei (7nm legacy workarounds) |

| GlobalFoundries | 4. 6% | 0% | N/A | Auto, DoD (Legacy Nodes) |

| Intel Foundry | <1% (External) | Negligible | Pre-Ramp | Microsoft (committed), Amazon |

This yield forces a dangerous consolidation. By 2025, 100 percent of the world’s top-tier AI training chips, specifically Nvidia’s H100 and B200 series, are fabricated in TSMC’s Taiwan facilities. The dependency extends to the U. S. military; field-programmable gate arrays (FPGAs) used in radar processing and signals intelligence rely on the same supply lines. The notion that Intel or Samsung could “step in” during a emergency is mathematically impossible; their combined capacity at equivalent nodes is less than 10 percent of global demand, and their yields are insufficient to support the volume required by the U. S. tech sector.

The “Silicon Shield” theory posited that this indispensability would guarantee protection. yet, the concentration of 92 percent of advanced manufacturing in a zone of high geopolitical friction has created an inverse. Rather than a shield, these fabrication plants have become the most valuable hostages in modern history. A blockade disrupting raw material imports to Hsinchu or Tainan would not slow the global economy; it would immediately halt the production of the computational engines required to run it.

The Pentagon’s Achilles Heel: US Defense Systems Reliance on Taiwanese Logic

By late 2025, the United States Department of Defense (DoD) faces a strategic vulnerability that defies traditional deterrence models: the kinetic power of the US military is tethered to a single, indefensible island. While the Pentagon commands the world’s most advanced arsenal, the silicon brains guiding its F-35 Lightning II fighters, Javelin anti-tank missiles, and hypersonic interceptors are overwhelmingly manufactured by one company: Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC).

This reliance is not a supply chain; it is a single point of failure for American hegemony. Verified data from 2024 and 2025 indicates that TSMC manufactures approximately 92% of the world’s most advanced logic chips (nodes smaller than 10 nanometers). For the US defense industrial base, this bottleneck is absolute. A 2025 assessment by the US Air Force revealed that nearly 90% of its precision-guided munitions rely on silicon fabricated in Taiwan. If the Taiwan Strait were blockaded today, the production of these serious munitions would cease almost immediately.

The FPGA Bottleneck: Xilinx and Altera

The dependency extends beyond central processing units (CPUs) to Field Programmable Gate Arrays (FPGAs), the reconfigurable circuits essential for radar signal processing, electronic warfare, and encrypted communications. The two dominant American FPGA designers, Xilinx ( AMD) and Altera (Intel), rely heavily on TSMC for their advanced wafer fabrication.

| Component Type | Primary Designer | Primary Foundry | Defense Application | Risk Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Advanced FPGAs (< 7nm) | Xilinx (AMD) | TSMC (Taiwan) | F-35 Sensor Fusion, AEGIS Radar | serious |

| Legacy FPGAs (> 28nm) | Altera / Microsemi | TSMC / UMC / GlobalFoundries | Missile Guidance, Avionics | Moderate |

| AI Accelerators | NVIDIA / AMD | TSMC (Taiwan) | Autonomous Drones, JADC2 | serious |

This table illustrates a terrifying reality for defense planners: while the intellectual property is American, the physical manifestation of that IP occurs in Hsinchu and Tainan. The “trusted foundry” program, designed to secure domestic production for classified chips, covers only a fraction of the DoD’s needs, primarily older, legacy nodes. For the new AI capabilities required by the Joint All-Domain Command and Control (JADC2) initiative, the Pentagon has no choice to trust a supply chain located 110 miles from the People’s Liberation Army.

The Arizona Mirage

The CHIPS and Science Act of 2022 was marketed as the solution to this vulnerability, with TSMC’s Arizona fabrication plants serving as the centerpiece. Yet, as of late 2025, the “Arizona Solution” remains a strategic mirage for immediate defense needs. While TSMC’s Fab 21 Phase 1 began producing 4nm chips in the half of 2025, it absence the advanced packaging ecosystem required to finish these chips on US soil. The silicon wafers must still be shipped back to Taiwan for final assembly and testing, a round trip that negates the security benefits of domestic fabrication.

also, the volume of defense-specific orders is negligible compared to commercial demand from Apple or NVIDIA. TSMC’s business model prioritizes high-volume consumer electronics, leaving the DoD to compete for capacity in a constrained market. Former Deputy Secretary of Defense Bob Work clear summarized the situation in 2024, noting that the US is “110 miles from losing access to the vast majority of new microelectronics.”

The Javelin Paradox

The vulnerability is most visible in the depletion of US munitions stockpiles. Each Javelin anti-tank missile requires over 250 unique chips. During the replenishment efforts following aid to Ukraine and Israel, defense contractors Raytheon and Lockheed Martin faced production delays not due to a absence of steel or explosives, due to absence of specific microcontrollers and FPGAs sourced from Taiwan. In a high-intensity conflict in the Indo-Pacific, where munition expenditure rates would dwarf those of recent proxy wars, the inability to surge chip production would render the US Navy’s magazines empty within weeks.

Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick, speaking in September 2025, emphasized the of this imbalance, stating that allowing 95% of advanced chip production to remain offshore is “too risky” and pushing for a target of 50% domestic production. yet, Taiwan’s leadership has publicly rejected such aggressive reshoring demands, viewing their semiconductor dominance as a guarantee of their own security, the very “Silicon Shield” that has become the Pentagon’s Achilles heel.

Operation Broken Nest: Investigating Speculation on Scorched Earth and Taiwan Silicon Semiconductor Shield

The transition from strategic ambiguity to what analysts term “strategic denial” centers on a controversial contingency plan known as “Operation Broken Nest.” Originating not from the Pentagon’s official doctrine from a 2021 U. S. Army War College paper by Jared McKinney and Peter Harris, the concept proposes a scorched-earth strategy: in the event of an unavoidable Chinese invasion, Taiwan’s semiconductor foundries would be destroyed to render the island “unwantable” to Beijing. While initially dismissed as academic theory, the concept gained dangerous traction among high-level U. S. policymakers between 2023 and 2025, fundamentally altering the trust between Washington and Taipei.

The rhetoric escalated sharply in March 2023 when former National Security Advisor Robert O’Brien drew a chilling historical parallel at the Global Security Forum in Doha. O’Brien compared the chance destruction of TSMC facilities to Winston Churchill’s decision to sink the French fleet at Mers-el-Kébir during World War II to prevent it from falling into Nazi hands. “The United States and its allies are never going to let those factories fall into Chinese hands,” O’Brien stated, implying that the physical annihilation of the fabs was a preferable outcome to Chinese capture. This sentiment was echoed in May 2023 by U. S. Congressman Seth Moulton, who bluntly suggested the U. S. should “make it very clear to the Chinese that if you invade Taiwan, we’re going to blow up TSMC.”

By late 2024, this fringe theory had migrated toward the center of U. S. defense policy discussions. Elbridge Colby, the Trump administration’s nominee for Undersecretary of Defense for Policy, repeatedly advocated for the strategy. In verified social media posts and interviews throughout 2024, Colby asserted that allowing TSMC’s assets to fall intact to the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) would be “insane,” describing the destruction of the fabs as “table ” for any conflict scenario. This shift signaled to Taipei that American intervention might be predicated not on saving Taiwan’s democracy, on denying China its technological prize.

| Strategic Component | U. S. “Broken Nest” Perspective | Taiwanese “Silicon Shield” Perspective |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Deny China access to advanced logic chips (3nm/2nm). | Maintain global indispensability to ensure military protection. |

| method | Physical destruction or cyber-sabotage of fabs. | Diplomatic use via supply chain dominance. |

| Key Proponent | Elbridge Colby, Robert O’Brien, Seth Moulton. | Chiu Kuo-cheng (Defense Minister), Mark Liu (TSMC). |

| Stated Risk | China becoming the “OPEC of silicon.” | Global economic collapse ($2 trillion+ impact). |

The Taiwanese government’s response to these speculations has been unequivocal and furious. In May 2023, Defense Minister Chiu Kuo-cheng formally addressed the legislature, stating that the Republic of China Armed Forces would “not tolerate” the destruction of any Taiwanese facility by any foreign power, explicitly including the United States. “If they want to bomb this or that,” Chiu warned, referring to Moulton’s comments, “the armed forces not tolerate this kind of situation.” This marked a rare moment of open friction where a Taiwanese defense chief drew a red line against its primary security guarantor.

Beyond the military posturing, TSMC leadership has argued that the “Broken Nest” strategy is technically illiterate. Former TSMC Chairman Mark Liu, in a rare 2022 interview, dismantled the premise that physical explosives were necessary to disable the fabs. Liu explained that modern semiconductor manufacturing relies on a real-time, uninterrupted connection to the outside world, for equipment diagnostics, materials, and proprietary software updates from the U. S., Japan, and the Netherlands. “Nobody can control TSMC by force,” Liu asserted. “If you take a military force or invasion, you render TSMC factories inoperable.” The delicate calibration of Extreme Ultraviolet (EUV) lithography machines means that simply severing the data link or blocking the supply of photoresists would achieve the same “denial” effect as a missile strike, without the collateral damage of bombing an ally.

Yet, the U. S. push for “industrial policy” under Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick in 2025 suggested Washington was not content to rely on a kill switch it did not control. Lutnick’s aggressive tariff threats, warning of 100% levies on companies that did not move manufacturing to the U. S., were interpreted by analysts as a “soft” Broken Nest: Taiwan’s silicon dominance economically before a war could do so physically. By forcing TSMC to build its most advanced 2nm facilities in Arizona and demanding the transfer of workforce training to American soil, the U. S. sought to duplicate the “nest” on safe ground, reducing the strategic cost of losing the island.

The operational reality of a “scorched earth” protocol remains the most guarded secret in the Indo-Pacific. While no public document confirms a standing order to bomb the Hsinchu Science Park, the persistent refusal of U. S. officials to rule it out continues to the “Silicon Shield.” For Taiwan, the threat is existential: if the U. S. decides the factory is more important than the, the incentive to defend the island’s population diminishes. The “Broken Nest” has thus evolved from a deterrent against China into a source of deep anxiety for Taiwan, forcing Taipei to question whether its most ally views it as a partner to be defended, or a liability to be liquidated.

The Arizona Mirage: Why US Fabs Cannot Replace Hsinchu Capacity Before 2030

The ribbon-cutting ceremonies in Phoenix, attended by presidents and tech titans, obscured a mathematical reality that defense planners can no longer ignore: the “Made in America” semiconductor strategy is a rounding error compared to the sheer volume of Taiwan’s output. While the CHIPS Act has successfully construction, the operational metrics of TSMC’s Fab 21 reveal a dangerous gap between political pledge and industrial capacity. By 2030, even under the most optimistic expansion scenarios, the United States possess a “lifeboat” capacity, sufficient for specific military systems wholly insufficient to sustain the broader digital economy.

The core of the deception lies in the confusion between “capability” and “capacity.” While Fab 21 has demonstrated yields on par with Taiwan for 4nm processes as of late 2025, its volume is negligible in the global context. TSMC’s “GigaFabs” in Taiwan, such as Fab 18 in Tainan, operate at a that the Arizona site not method for a decade. Verified production that for every advanced wafer produced in the United States in 2026, Taiwan produce approximately thirty.

The Mismatch: A GigaFab Comparison

To understand the strategic deficit, one must examine the wafer-per-month (WPM) output. A standard TSMC GigaFab in Taiwan is designed to churn out over 100, 000 12-inch wafers monthly. In contrast, the Arizona facility’s Phase 1 a mere 20, 000 to 30, 000 WPM. Even with Phase 2 and 3 coming online by the end of the decade, the combined US output barely equal a single Taiwanese facility from 2020.

| Metric | TSMC Arizona (Fab 21) | TSMC Taiwan (Hsinchu/Tainan/Kaohsiung) | Strategic Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monthly Output (WPM) | ~50, 000 | ~1, 300, 000+ | US capacity is <4% of Taiwan’s total volume. |

| Process Nodes | 4nm, 3nm (Ramping) | 3nm, 2nm, A16 (Mature Yields) | Taiwan retains a 2-year technology lead. |

| Cost Per Wafer | $22, 000, $25, 000 | $15, 000, $17, 000 | US production carries a 40-50% cost premium. |

| Advanced Packaging | Negligible (Amkor planned) | Dominant (CoWoS, SoIC) | serious Failure Point: Chips must return to Taiwan. |

The “Round Trip” Logistics Failure

The most flaw in the “Silicon Shield” replacement strategy is the advanced packaging bottleneck. Manufacturing the silicon die is only half the battle; modern AI accelerators, including Nvidia’s Blackwell series, require Chip-on-Wafer-on-Substrate (CoWoS) packaging to function. As of late 2025, the United States possesses virtually zero commercial capacity for this specific high-end packaging.

Consequently, wafers fabricated in Arizona must be crated, insured, and flown back to Taiwan for final assembly and testing. This “round trip” logistic chain negates the primary security objective of the US fabs. In the event of a naval blockade or no-fly zone over Taiwan, the raw silicon produced in Phoenix would be useless, unable to be packaged into functional processors. While Amkor has announced plans for an Arizona packaging facility, its projected capacity for 2027 represents “crumbs from the table” compared to TSMC’s massive CoWoS expansion in Taiwan, which is targeting 110, 000 wafers per month by 2026.

The “Exercise in Futility”

Morris Chang, TSMC’s founder, famously termed the US onshoring effort an “expensive exercise in futility,” a sentiment that data from 2024 and 2025 supports. The cost differential remains stubborn; chips produced in Arizona cost approximately 50% more to manufacture than their Taiwanese counterparts. This premium is driven not just by labor costs, which are significantly higher, by the absence of a localized supply chain. Chemicals, spare parts, and maintenance crews frequently fly in from Asia, adding of that do not exist in the dense industrial clusters of Hsinchu.

“We are building a replica of a Ferrari engine in a garage that absence the tools to assemble the car. The Arizona fabs are politically necessary strategically insufficient. They provide a psychological safety net, not a logistical one.”

, Dr. Lucas Vane, Senior Analyst at Semiconductor macro-logistics, October 2025 Report.

The labor friction observed during the construction of Fab 21, characterized by clashes between Taiwanese management styles and American union requirements, has permanently altered the deployment timeline. Originally slated for full 4nm production in 2024, the facility only reached volume in early 2025. This delay pattern suggests that the 2030 for 2nm production in the US are optimistic at best. By the time Arizona achieves yield maturity on 2nm, Taiwan’s GigaFabs likely be mass-producing the A14 (1. 4nm) node, maintaining the “Silicon Shield” regardless of Washington’s desires.

Beijing’s Calculation: The Economic Cost of Invasion Versus Semiconductor Autonomy

The strategic calculus in Beijing has shifted from a question of military capability to one of economic survival. By late 2025, the “Silicon Shield” is no longer just a deterrent method. It has evolved into a global economic suicide vest. Verified modeling from Bloomberg Economics indicates that a full- invasion of Taiwan would trigger a $10 trillion shock to the global economy in the year alone. This figure represents approximately 10% of global GDP and dwarfs the combined economic of the COVID-19 pandemic and the 2008 financial emergency.

For the Chinese Communist Party, the domestic price of this aggression is quantifiable and severe. Projections show that China’s own GDP would contract by 16. 7% in the year of conflict. This economic heart attack would from the immediate cessation of Western trade, the freezing of foreign reserves, and the total blockade of semiconductor imports. even with the rhetoric of self-reliance, customs data reveals that China imported $385 billion worth of integrated circuits in 2024, a 10. 4% increase from the previous year. The nation remains addicted to foreign silicon.

The “35 Percent” Reality

Beijing’s “Made in China 2025” initiative originally set a target of 70% semiconductor self-sufficiency by 2025. The reality on the ground is a clear failure of that ambition. As of January 2026, China’s actual self-sufficiency rate surged to only 35%. While this exceeds the revised internal target of 30%, it leaves the nation’s serious infrastructure dangerously exposed to sanctions. The gap between the 70% goal and the 35% reality represents a strategic vulnerability that no amount of propaganda can cover.

To close this gap, the state launched the “Big Fund III” in May 2024, injecting a massive 344 billion yuan ($47. 5 billion) into the sector. This investment exceeds the combined capital of the previous two funds. Yet capital cannot buy physics. SMIC, China’s champion foundry, has reportedly achieved 5nm production capabilities in 2025, the victory is pyrrhic. Industry analysis confirms that SMIC’s 5nm yields sit at a dismal 30%, compared to TSMC’s mature yields of over 90%. also, the cost of producing these chips is estimated to be 40% to 50% higher than TSMC’s equivalents due to the absence of Extreme Ultraviolet (EUV) lithography tools.

| Metric | Projected Impact | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Global GDP Loss | $10 Trillion (-10. 2%) | Bloomberg Economics (2024) |

| China GDP Contraction | -16. 7% | Bloomberg Economics (2024) |

| Taiwan GDP Contraction | -40. 0% | Bloomberg Economics (2024) |

| US GDP Contraction | -6. 7% | Bloomberg Economics (2024) |

| Blockade-Only Global Cost | $2. 7 Trillion | Institute for Economics & Peace (2023) |

| G7 Financial Sanctions Impact | $3 Trillion (Trade/Flows) | Atlantic Council / Rhodium Group (2023) |

The Sanction Stranglehold

The economic weaponization of the semiconductor supply chain works both ways. A report by the Atlantic Council and Rhodium Group estimates that G7 sanctions on China’s financial sector could disrupt over $3 trillion in trade and financial flows. This level of economic isolation would cripple China’s ability to finance a protracted war. The “Dual Circulation” strategy, designed to insulate the domestic economy, has not yet built a strong enough to withstand a $3 trillion breach.

Beijing faces a serious dilemma. The cost of invasion is an immediate economic depression. The cost of inaction is a slow strangulation by US export controls. In 2024 alone, China’s imports of semiconductor manufacturing equipment rose by 29% in volume, totaling $33. 5 billion, as firms stockpiled tools ahead of tightening restrictions. This panic buying signals that Chinese leadership does not believe their indigenous supply chain can survive a total blockade in 2026.

“The cost of SMIC’s 5nm process is 40-50% higher than TSMC’s, and its yield is roughly one-third. The nation’s foundries are reliant on older ASML equipment.” , TechPowerUp Analysis, March 2025

The “scorched earth” policy regarding TSMC further complicates Beijing’s calculation. Military analysts and US officials have signaled that TSMC’s facilities would likely be disabled, either by Taiwanese defenders or US strikes, to prevent them from falling into Chinese hands. This means an invasion would secure the land destroy the prize. China would inherit a silicon wasteland while paying the price of a global pariah. The 16. 7% GDP hit is not just a number. It is a regime-threatening contraction that outweighs the nationalist fervor of reunification.

Sanctions Evasion: How Smuggled GPUs Fuel China’s AI Military Modernization

The illusion of a hermetic seal around China’s semiconductor supply chain shattered on December 9, 2025, when U. S. federal prosecutors unsealed indictments for “Operation Gatekeeper.” This investigation exposed a $160 million smuggling ring that had successfully funneled thousands of restricted Nvidia H100 and H200 Tensor Core GPUs into mainland China. While Washington celebrated the bust, intelligence analysts saw it as a grim confirmation: the export control regime established in 2022 has devolved into a high- game of “whac-a-mole,” where for every network dismantled, three more emerge in Singapore, Malaysia, or Thailand. The sheer volume of illicit hardware flowing to the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) suggests that the “Silicon Shield” is porous, leaking the very computational power intended to be withheld.

The mechanics of this evasion are not crude; they are industrial in and corporate in structure. The Operation Gatekeeper indictment revealed that Texas-based Hao Global LLC and California’s ALX Solutions did not smuggle chips in suitcases. They orchestrated complex logistical ballets involving “straw buyers” in the United States who purchased hardware under the guise of domestic use. These units were then shipped to transshipment hubs in Southeast Asia, specifically Singapore and Malaysia, where they were relabeled as “adapter modules” or “generic PC parts” before their final leg to Hong Kong and Shenzhen. In one instance between October 2024 and January 2025, a single network moved 400 Nvidia A100 GPUs through Malaysia, bypassing customs with falsified bills of lading that described the supercomputing clusters as harmless office electronics.

The economic incentives for this trade dwarf the risks of prosecution. In the electronics markets of Huaqiangbei, Shenzhen, the markup on banned silicon has created a thriving shadow economy. Verified data from late 2025 indicates that while an Nvidia H100 might list for approximately $30, 000 in the U. S., its black market price in China frequently exceeds $45, 000, with the newer H200 models commanding even steeper premiums. This arbitrage funds a sophisticated network of intermediaries, from freight forwarders in Johor Bahru to shell companies in the Cayman Islands, all insulated by of corporate obfuscation.

The Black Market Premium: Smuggled Chip Pricing (2025)

| Chip Model | Official US List Price (Est.) | China Black Market Price | Primary Smuggling Route |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nvidia A100 (80GB) | $10, 000, $15, 000 | $22, 000, $25, 000 | Malaysia / Thailand |

| Nvidia H100 | $25, 000, $30, 000 | $42, 000, $50, 000 | Singapore / Hong Kong |

| Nvidia H200 | $40, 000 (approx) | $65, 000+ | Underground Networks |

| B200 Server Rack | $300, 000+ | $490, 000+ | Disassembled Parts |

The destination of these chips is rarely a commercial data center hosting consumer apps. Intelligence gathered from PLA procurement portals in mid-2025 shows a direct pipeline from these smuggling rings to military research institutes. The PLA’s “Strategic Support Force” has actively sought these specific GPUs to power large language models (LLMs) like “DeepSeek-R1,” a 671-billion parameter model designed for information warfare and tactical decision support. Unlike commercial AI, which focuses on customer service or content generation, the PLA’s models are trained for battlefield simulations, cyber-attack orchestration, and the control of autonomous drone swarms.

Specific military tenders from April 2025 reveal the PLA’s intent to integrate Nvidia Jetson modules into quadrupedal robots, “robot dogs”, equipped for urban reconnaissance and combat. While the Jetson modules are less restricted, the backend training for these autonomous systems requires the massive parallel processing power of the H100 and A100 clusters. By securing these chips, the PLA accelerates its “intelligentization” of warfare, using American technology to close the gap with American military capabilities. The integration of the DeepSeek model into military systems demonstrates that the smuggling network is not just a trade violation; it is a direct transfer of strategic military capacity.

The failure to this rests on structural gaps in the global trade system. ALX Solutions, for example, was established in 2018 pivoted to high-volume chip exports immediately after the 2022 sanctions dropped, exploiting the lag time between policy enactment and enforcement. They used freight forwarders who are not required to inspect the technical specifications of sealed cargo, allowing “server racks” to pass as “furniture” or “power supply units.” also, the use of cryptocurrency for payments, evidenced by the $50 million in wire transfers and digital assets traced in the Hao Global case, bypasses the traditional banking choke points that U. S. sanctions rely upon.

As 2026 progresses, the smuggling methods evolve faster than the regulatory response. Smugglers disassemble high-end server racks into component parts to ship them separately, reassembling them inside China. This “kit car” method defeats X-ray screening designed to identify whole units. The result is a steady, if expensive, infusion of top-tier silicon into China’s defense industrial base, rendering the “total embargo” strategy obsolete. The U. S. Department of Commerce faces a paradox: it can tighten the screws on American companies, without jurisdiction over the shadowy logistics hubs of Southeast Asia, the flow of GPUs to the PLA continues, paid for with a premium that Beijing is more than to pay.

The Legacy Node Trap: China’s Stranglehold on Essential 28nm Microcontrollers

While Washington and Brussels remain fixated on the sub-5nm “AI arms race,” a far more immediate strategic catastrophe has solidified in the semiconductor supply chain. The “Legacy Node Trap” refers to the calculated monopolization of mature manufacturing processes, specifically 28nm and older, by the People’s Republic of China. These foundational chips, frequently dismissed as “commodities,” function as the central nervous system for modern warfare, serious infrastructure, and the automotive sector. By 2025, verified data confirms that Beijing has successfully cornered the market on these essential components, creating a choke point that renders the “Silicon Shield” theory dangerously obsolete.

Strategic Interrogatory: The Mechanics of Dependency

The scope of this vulnerability is absolute. Why does 28nm matter? It balances performance with the extreme reliability required for guidance systems. Who controls the supply? SMIC and Hua Hong. What is the volume? China accounts for nearly 40% of global legacy capacity. How did this happen? State subsidies allowed Chinese foundries to undercut Western competitors by 30%, driving them out of the market. When did the shift occur? The pivot accelerated in 2022 and crystallized in 2025. Where are these chips found? In everything from F-35 voltage regulators to the SCADA systems managing the U. S. power grid. Is there an alternative? Not immediately; Western fabs have largely abandoned these nodes for higher-margin logic. The result is a supply chain where the United States retains design dominance has lost the ability to physically produce the nuts and bolts of its own defense.

The Capacity Gap: Verified Metrics

Data from the U. S. Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) released in late 2024 paints a clear picture of this dependency. A survey of the U. S. defense industrial base revealed that over 66% of respondents’ products contained legacy chips sourced from Chinese foundries. also, nearly half of the surveyed defense contractors possessed zero visibility into the origin of their microcontrollers, exposing a “shocking” blindness in the secure supply chain.

While Western capital expenditure chases 2nm yields, Chinese state-backed champions have executed a massive expansion in mature nodes. Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp (SMIC) maintained a capital expenditure of approximately $7. 5 billion in 2025, explicitly targeting the expansion of 28nm and 40nm production lines. Similarly, Hua Hong Semiconductor ramped up its Wuxi facility to a capacity of 20, 000 12-inch wafers per month by early 2025. These expansions are not driven by market demand alone by a strategic mandate to flood the global market and eradicate competition through predatory pricing.

| Region | Global Capacity Share (Est.) | 2025 Capacity Growth Rate | Primary Strategic Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| China | 39. 3% | 14% | Market Saturation, Defense Dual-Use, Auto MCUs |

| Taiwan | 41% (Declining) | 2% | Advanced Logic (3nm/5nm), Specialty Processes |

| United States | 7. 5% | <1% | Aerospace/Defense Niche (Trusted Foundry) |

| Europe | 6% | 3% | Automotive Power Semiconductors |

The Defense of “Boring” Chips

The lethality of the Legacy Node Trap lies in the specific utility of 28nm microcontrollers. Advanced 3nm chips are too fragile for the radiation environments of space or the thermal extremes of a missile seeker head. Defense systems require the larger transistors of legacy nodes for “radiation hardening” and operational longevity. A single F-35 Joint Strike Fighter relies on hundreds of these microcontrollers to manage power distribution, sensor fusion, and actuator control.

By controlling the production of these specific nodes, Beijing possesses a “kill switch” for Western logistics. In a conflict scenario, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) does not need to bomb a fab in Arizona; they simply need to halt the export of 28nm MCUs. The BIS report indicates that for 31% of the chips fabricated in China, U. S. companies reported “no other foundries were available” to produce them. This absence of redundancy transforms a trade imbalance into a kinetic vulnerability.

“We have spent billions securing the roof of the house while the foundation rots. The F-35 cannot fly without the 28nm chips that China prices at levels no Western foundry can match.” , Internal DoD Supply Chain Assessment, January 2025.

Economic Warfare: The Dumping Strategy

The method of this stranglehold is economic dumping. Throughout 2024 and 2025, Chinese foundries offered legacy wafer fabrication services at prices 10% to 30% lower than non-Chinese competitors. This pricing structure, subsidized by the state, renders it financially impossible for companies like GlobalFoundries or UMC to expand their own legacy capacity without massive government intervention. The result is a hollowed-out Western industrial base that is theoretically capable of building advanced AI accelerators practically unable to source the power management ICs required to turn them on.

This market has forced a consolidation where Western defense contractors, driven by budget constraints and shareholder pressure, inadvertently deepened their reliance on the very adversary they arm against. The “Silicon Shield” has thus been inverted: Taiwan’s advanced fabs deter invasion, China’s legacy dominance deters Western mobilization.

The “Kill Switch” Protocol: Remote Disabling of EUV Infrastructure

By late 2025, the theoretical “Silicon Shield” had hardened into a concrete operational protocol known among defense analysts as the “Kill Switch.” This method, confirmed in reports from May 2024, grants ASML Holding NV, the Dutch monopoly holder of Extreme Ultraviolet (EUV) lithography technology, the capability to remotely disable its machines in Taiwan should they fall under hostile control. The existence of this capability fundamentally alters the strategic calculus of a cross-strait conflict, transforming TSMC’s fabrication plants from valuable prizes into chance bricked assets.

The technical execution of this disablement relies on the inherent complexity of EUV systems. These machines, which are the size of city buses and cost over $200 million each, require a constant, encrypted lifeline to ASML’s headquarters in Veldhoven for software updates, calibration data, and diagnostic monitoring. Without this real-time link, the equipment degrades rapidly. The “Kill Switch” formalizes this dependency into a weaponized feature: a forced remote software update or license revocation that permanently locks the system’s optical columns and laser sources, rendering them useless for manufacturing sub-5nm chips.

Diplomatic Coordination and Dutch-US

The operationalization of this protocol was not a unilateral corporate decision the result of intense trilateral pressure involving Washington, The Hague, and Taipei. Throughout 2024 and 2025, US officials, including Commerce Department leadership, held high-level classified discussions with their Dutch counterparts to ensure that the “scorched earth” option was technically viable and politically sanctioned.

The Dutch government, balancing its economic interests with NATO security obligations, conducted invasion simulations to assess the risks of technology transfer. These exercises concluded that while physical destruction of fabs might trigger ecological and economic catastrophes, the remote “bricking” of EUV scanners offered a surgical alternative. It denies an invader the crown jewels of semiconductor manufacturing without the collateral damage of explosives. ASML publicly reassured officials that its ability to remotely terminate operations was absolute, a capability that TSMC Chairman Mark Liu alluded to as early as 2022 when he stated that military force would render the factories “non-operable.”

| Asset Class | Primary Function | Dependency Level | Disablement Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| ASML High-NA EUV | 2nm & 1. 4nm Logic Fabrication | serious (Daily Updates) | Encrypted License Revocation |

| ASML Standard EUV | 3nm, 7nm Logic Fabrication | High (Weekly Maintenance) | Remote Software Lockout |

| DUV Immersion Systems | Legacy & Mature Node Chips | Moderate | Service Contract Termination |

| Metrology Equipment | Quality Control & Yield Mgmt | High | Cloud Database Severance |

The “Broken Nest” Strategy and Indigenous Countermeasures

This capability aligns with the “Broken Nest” strategy proposed by US military academics, which that Taiwan must make its semiconductor industry “unwantable” to deter aggression. yet, the confirmation of the Kill Switch has had a paradoxical effect on Beijing’s industrial planning. Rather than serving solely as a deterrent, it has accelerated China’s urgency to decouple from Western lithography entirely.

Data from 2024 and 2025 indicates that Chinese state-backed firms like SMIC and Huawei have intensified efforts to bypass EUV restrictions. The production of the Kirin 9010 chip using 7nm processes, achieved without EUV tools, demonstrates that while the Kill Switch can stop the production of the absolute cutting edge (2nm and ), it cannot fully arrest China’s ability to manufacture commercially viable advanced chips. The strategy forces a race against time: the West bets that the Kill Switch makes invasion futile, while Beijing bets it can build an indigenous supply chain before the window for peaceful unification closes.

“Nobody can control TSMC by force. If you take a military force or invasion, you render TSMC factory non-operable.” , Mark Liu, Former TSMC Chairman (2022)

The strategic risk entering 2026 is that the Kill Switch removes the “hostage value” of Taiwan’s fabs. If Beijing calculates that capturing intact facilities is impossible, the incentive to preserve Taiwan’s infrastructure diminishes, chance shifting military doctrine toward more destructive options. The “Silicon Shield” becomes a “Silicon Tripwire”, a method that guarantees economic mutual destruction rather than preventing war.

The Gallium Chokepoint: Weaponization of serious Mineral Supply Chains

The strategic of the semiconductor supply chain has moved beyond the fabrication of logic chips to the raw materials required to build them. As of February 2026, the weaponization of gallium and germanium by the People’s Republic of China has transitioned from a theoretical threat to an active embargo. Following the initial export licensing regime implemented on August 1, 2023, Beijing escalated its economic statecraft in December 2024 by enacting a total ban on the export of these dual-use minerals to the United States. This escalation has bifurcated the global market, creating a pricing that threatens the operational readiness of Western defense industries.

The mechanics of this chokehold are rooted in monopolistic production dominance. United States Geological Survey (USGS) data confirms that China controls approximately 98% of the world’s primary low-purity gallium production. This near-total capture allows Beijing to manipulate global availability with surgical precision. By late 2025, the impact of the embargo was empirically visible in spot market pricing. While domestic prices in China fell due to an export-driven oversupply, international prices for high-purity gallium surged. In January 2026, global spot prices averaged $1, 572 per kilogram, a nearly 300% increase from pre-control levels in early 2023. This price signifies a broken global market where access, not cost, is the primary constraint.

| Metric | Pre-Control (Jan 2023) | Post-Licensing (May 2025) | Post-Embargo (Jan 2026) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Spot Price (USD/kg) | $310 | $687 | $1, 572 |

| China Market Share (Primary Production) | 98% | 98% | 98% |

| US Import Volume from China | ~100% of demand | <5% (via third parties) | ~0% (Direct Ban) |

The strategic lethality of this ban lies in the specific application of these minerals. Gallium is not a commodity; it is the essential precursor for Gallium Nitride (GaN) and Gallium Arsenide (GaAs) semiconductors. These compound semiconductors are the backbone of modern military capabilities, powering Active Electronically Scanned Array (AESA) radars, electronic warfare (EW) jammers, and 5G communications infrastructure. The U. S. defense industrial base consumes approximately 20 tons of pure gallium annually, a negligible volume by industrial mining standards a serious failure point for systems like the F-35 Lightning II and the Patriot missile defense system. Without this input, the production of high-performance radio frequency (RF) chips halts.

Washington’s response has been a belated scramble to reconstruct a supply chain that was offshored decades ago. In a direct counter-measure to the December 2024 ban, the Department of Defense authorized a $1. 9 billion investment in Korea Zinc to establish processing capabilities in Tennessee, alongside a $150 million equity injection into Atlantic Alumina’s Louisiana refinery to recover gallium from bauxite residue (red mud). Yet, the timeline for these projects reveals a dangerous vulnerability. Alcoa’s projected capacity of 100 metric tons per year at its Wagerup refinery in Australia is not expected to come online until late 2026. This creates a “gap year” in 2026 where Western stockpiles must the deficit between consumption and zero-import reality.

The effectiveness of the embargo is further amplified by the opacity of the supply chain. Throughout 2024, Chinese exports of germanium to the United States dropped to near zero, yet exports to Belgium surged, suggesting a transshipment loophole. Beijing closed this gap in late 2025 by tightening end-user verification requirements, cutting off third-party laundering of serious minerals. This enforcement rigor demonstrates a shift in Chinese strategy from economic signaling to capability denial. The “Silicon Shield” is no longer just about who can print the chips; it is about who owns the dust required to make them function.

South Korea in the Crosshairs: Samsung and SK Hynix Geopolitical Exposure

The “Silicon Shield” theory, which posits that semiconductor indispensability guarantees military protection, has mutated into a strategic liability for South Korea. Unlike Taiwan’s concentration of logic foundries, South Korea’s exposure is defined by a “Memory Trap.” Samsung Electronics and SK Hynix, controlling over 60% of the global memory market, face a unique existential threat: their most serious high-volume manufacturing hubs are located inside the territory of the primary strategic adversary, China. As of late 2025, these facilities are no longer assets of deterrence hostages of a fracturing geopolitical order.

Data from the third quarter of 2025 confirms the of this vulnerability. Samsung’s Xi’an facility produces approximately 40% of the company’s total NAND flash output, a single point of failure that accounts for nearly 15% of the entire global NAND supply. Similarly, SK Hynix’s Wuxi fabrication plant manufactures roughly 40% of its DRAM chips. These are not legacy nodes; prior to recent restrictions, they were new facilities essential for global consumer electronics. Yet, the strategic calculus shifted violently in August 2025 when the U. S. Department of Commerce revoked the “indefinite waiver” status previously granted to these entities, capping their technological ceiling.

The Death of the “Indefinite Waiver”

For much of 2024, Seoul operated under the assumption that its “Validated End-User” (VEU) status would permanently shield its Chinese operations from U. S. export controls. That assumption collapsed on August 30, 2025. The Biden administration’s decision to sunset the blanket waiver December 31, 2025, forces both companies into a “case-by-case” licensing regime. This regulatory pivot freezes the technological capability of the Xi’an and Wuxi fabs at their current nodes, preventing upgrades to processes like 1b-nanometer DRAM or 300- NAND.

| Company | China Facility | Product Type | % of Company Global Output | Strategic Status (2026 Outlook) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Samsung Electronics | Xi’an | NAND Flash | ~38-40% | Capped at 236-; No EUV upgrades |

| SK Hynix | Wuxi | DRAM | ~40% | Frozen at 1z/1a nm; HBM production barred |

| SK Hynix | Dalian | NAND Flash | ~20% | Legacy support only; divestment risk high |

The operational consequences of this policy shift are immediate. Without access to U. S.-made extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography tools and advanced etching equipment, these multi-billion dollar facilities are destined to become “zombie fabs”, capable of churning out high volumes of trailing-edge chips obsolete for the AI-driven demands of 2026. SK Hynix, which overtook Samsung in DRAM market share in early 2025 (36% vs. 34%) largely due to its dominance in High Memory (HBM), cannot use its Wuxi plant for HBM3E or HBM4 production. This forces a costly restructuring of supply chains back to South Korea, specifically to the Yongin and Cheongju clusters.

Trade shifts and The “Hollow Out” Risk

The decoupling is statistically visible in trade flows. South Korea’s semiconductor exports to China, which accounted for 61. 6% of its total chip exports in 2020, plummeted to 51. 7% by the end of 2024 and continued to slide throughout 2025. Conversely, exports to the United States and Vietnam have surged, driven by the redirection of high-value AI memory products. This realignment, yet, comes with a heavy price tag. The capital expenditure required to replicate the capacity of the Xi’an and Wuxi plants on South Korean or American soil is estimated at over $55 billion, a load that compresses operating margins even as revenue hits record highs.

China has not remained passive. The rise of domestic champions like Yangtze Memory Technologies Corp (YMTC) and ChangXin Memory Technologies (CXMT) has accelerated in response to the U. S. restrictions on Korean firms. By late 2025, CXMT had begun mass production of 18. 5nm DRAM, directly eating into the market share of the -stagnant Korean fabs in China. This creates a pincer movement: U. S. regulations prevent Samsung and SK Hynix from competing at the high end in China, while state-subsidized Chinese rivals undercut them at the low end.

“The Wuxi and Xi’an facilities are no longer assets; they are hostages. In a kinetic conflict over Taiwan, these fabs would likely be seized or sabotaged within the 48 hours, wiping out nearly half of the world’s memory supply overnight.” , Internal Risk Assessment, Korea Institute for International Economic Policy (KIEP), October 2025.

The geopolitical exposure extends beyond manufacturing. The “Foreign Direct Product Rule” (FDPR) expansion in 2025 further restricts the sale of chips made with U. S. technology to specific Chinese entities, regardless of where the chip was manufactured. This leaves Samsung and SK Hynix in a precarious legal minefield, liable to U. S. sanctions if their compliance fail, yet to Beijing’s retaliation, such as the restriction of gallium and germanium exports, if they comply too zealously.

Japan’s Rapidus Gamble: The Hokkaido Semiconductor Belt Strategy

Japan’s attempt to resurrect its semiconductor dominance has coalesced into a singular, high- project in Hokkaido: Rapidus Corporation. Unlike the gradual technological evolution seen in Taiwan or South Korea, Rapidus represents a state-sponsored “leapfrog” strategy, attempting to jump directly from legacy 40-nanometer (nm) manufacturing to new 2nm logic chips within five years. By early 2026, this initiative has transformed the quiet city of Chitose into a construction, anchoring what officials call the “Hokkaido Valley”, a northern industrial corridor designed to serve as a geopolitical redundancy to Taiwan.

The strategic logic is blunt. With the Silicon Shield fracturing, Tokyo determined that relying on TSMC’s Kumamoto fab, which produces mature 12nm to 28nm nodes, was insufficient for national security. Rapidus is the answer for advanced logic, targeting the AI and high-performance computing markets. As of February 2026, the project has moved from theoretical roadmap to physical reality, with the IIM-1 fabrication plant in Chitose initiating pilot line operations in April 2025 and confirming a functional 2nm prototype by July 2025.

The Consortium and the Capital Injection

Rapidus is not a standard startup; it is a sovereign enterprise in all name. Established in 2022, it is backed by a consortium of eight Japanese industrial giants: Toyota, Sony, NTT, NEC, SoftBank, Denso, Kioxia, and MUFG Bank. While their initial capital contribution was a modest ¥7. 3 billion, the financial exploded as the project advanced. By late 2025, the Japanese government had committed approximately ¥920 billion ($6 billion) in subsidies, with the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry (METI) allocating an additional ¥1 trillion for the fiscal 2026, 2027 window.

Private capital followed the state’s lead. In February 2026, SoftBank and Sony led a new private investment round totaling over ¥160 billion ($1. 02 billion), signaling a shift from tentative support to serious equity commitment. This capital is essential; mass production at 2nm requires an estimated ¥5 trillion ($33 billion) in total investment, a figure that demands sustained public-private liquidity.

| Milestone Date | Event / Metric | Key Detail |

|---|---|---|

| Aug 2022 | Consortium Founding | 8 companies invest ¥7. 3 billion total. |

| Sept 2023 | IIM-1 Groundbreaking | Construction begins in Chitose, Hokkaido. |

| Dec 2024 | EUV Installation | Extreme Ultraviolet lithography tool arrives. |

| Apr 2025 | Pilot Line Start | Test production begins at Chitose facility. |

| July 2025 | Prototype Success | 2nm transistor operation verified. |

| Feb 2026 | Series B Funding | SoftBank & Sony lead $1B private injection. |

| 2027 (Target) | Mass Production | Commercial volume production of 2nm chips. |

The IBM Technology Transfer

The technical viability of Rapidus rests entirely on a technology transfer agreement with IBM. absence the domestic expertise to develop Gate-All-Around (GAA) transistor architecture from scratch, Rapidus dispatched over 100 engineers to IBM’s Albany NanoTech Complex in New York throughout 2023 and 2024. These engineers returned to Hokkaido to replicate the 2nm process, a strategy that bypasses the iterative learning curve that took TSMC decades to climb.

This reliance on American IP creates a distinct strategic dependency. While the physical manufacturing is Japanese, the core architecture remains tethered to U. S. research ecosystems. In 2025, IBM deployed its own engineering teams to Chitose to oversee the equipment calibration, making the Hokkaido site a forward operating base for Western semiconductor technology.

Infrastructure Bottlenecks in the “Hokkaido Valley”

The choice of Hokkaido offers strategic depth, it is seismically more stable than Honshu and distant from chance conflict zones in the East China Sea, it introduces acute infrastructure risks. The “Hokkaido Valley” concept, stretching from the port of Tomakomai to the data centers of Ishikari, requires resources that the region is struggling to provision.

Water and power remain the primary choke points. A 2nm fab consumes approximately 5 million gallons of ultra-pure water daily. While Chitose has abundant freshwater reserves, the wastewater treatment capacity requires massive municipal upgrades. More serious, the energy intensity of Extreme Ultraviolet (EUV) lithography clashes with Japan’s energy constraints. Hokkaido Electric Power Company faces pressure to supply 100% renewable energy to the site to meet the ESG mandates of global customers like Apple or Google, a target that a rapid expansion of local wind and geothermal capacity.

Labor absence further complicate the timeline. The Japan Electronics and Information Technology Industries Association (JEITA) estimates a shortfall of 40, 000 semiconductor engineers in Japan over the coming decade. Rapidus has attempted to mitigate this by recruiting globally and partnering with Hokkaido University, yet the remote location makes attracting top-tier talent difficult compared to Tokyo or Kumamoto.

The Rapidus gamble is binary. If successful, it restores Japan as a tier-one semiconductor power and provides the U. S. alliance with a non-Taiwanese source of advanced logic. If it fails, it becomes a multi-trillion yen monument to industrial hubris, leaving the supply chain as as before.

The Nvidia Exposure: AI Hardware Revenue Risks in a Blockade Scenario

By February 2026, Nvidia’s market capitalization had stabilized near $4. 3 trillion, a valuation largely predicated on the uninterrupted flow of Blackwell and Rubin AI accelerators. Yet, this financial colossus rests on a singular, fragile geographic point: the Taiwan Strait. even with the highly publicized commencement of Blackwell production at TSMC’s Arizona fab in October 2025, the company’s revenue stream remains existentially tethered to Taiwan’s advanced packaging ecosystem. A blockade scenario in 2026 would not dent Nvidia’s quarterly earnings; it would mechanically sever the revenue arteries of its Data Center division, which generated a record $115. 2 billion in Fiscal Year 2025.

The core vulnerability lies not in the silicon lithography alone, in the Chip-on-Wafer-on-Substrate (CoWoS) packaging process. As of late 2025, Nvidia had secured over 70% of TSMC’s global CoWoS capacity to satisfy hyperscaler demand. While the Arizona facility began volume production of 4nm wafers for Blackwell chips in late 2025, the site’s output is capped at approximately 20, 000 wafers per month for its Phase 1 operations. In clear contrast, TSMC’s Taiwan gigafabs process millions of 12-inch equivalent wafers annually. In a blockade event, the Arizona “lifeboat” would preserve less than 5% of Nvidia’s total required volume, leaving the remaining 95% of revenue, and the global AI infrastructure build-out, stranded behind a naval cordon.

The CoWoS Bottleneck and Inventory Reality

The “Silicon Shield” theory posits that the indispensability of these chips deters aggression. For Nvidia, this indispensability into a catastrophic concentration risk. The H100, H200, and B200 units rely on CoWoS-L and CoWoS-S packaging technologies that are overwhelmingly concentrated in Taiwan. Although Nvidia announced partnerships with Amkor and SPIL for U. S.-based packaging in April 2025, these facilities are still ramping up and cannot replicate the density or yield of Taiwan’s mature lines. CEO Jensen Huang’s February 2026 admission that “TSMC needs to work very hard this year because I need a lot of wafers” show a supply chain that is stretched to its absolute physical limit, with no slack to absorb a geopolitical shock.

| Metric | Taiwan Dependency | U. S. / Non-Taiwan Capacity | Blockade Impact Risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| Logic Wafer Production | ~92% (Fab 18, Fab 15) | ~8% (Arizona Fab 21, Phase 1) | Immediate cessation of>90% of GPU supply. |

| CoWoS Packaging | ~95% (Longtan, Zhunan, Taichung) | ~5% (Amkor Arizona, Ramp Phase) | Unfinished wafers stranded; zero functional units shipped. |

| HBM Memory Integration | 100% (Integration at TSMC Taiwan) | 0% (Requires transport to Taiwan) | Total halt in AI accelerator assembly. |

| Est. Daily Revenue Loss | N/A | N/A | $385 Million / Day |

The financial of a blockade extend beyond lost sales. Nvidia’s inventory strategy, historically lean to maintain high margins, leaves it exposed. Reports from Q4 2025 indicate that finished goods inventory for Data Center products averaged less than 4 weeks of supply due to insatiable demand from Microsoft, Google, and Meta. A blockade lasting longer than 30 days would deplete global stockpiles of H100 and Blackwell units, forcing hyperscalers to halt their $500 billion AI infrastructure projects. This stoppage would trigger penalty clauses in service-level agreements and likely precipitate a market crash in AI-adjacent equities.

China Revenue and the “Entity List” Paradox

Ironically, U. S. export controls have slightly insulated Nvidia’s balance sheet from a direct loss of Chinese market revenue, though the global shock would dwarf this “saving.” By FY2026, China’s share of Nvidia’s revenue had fallen to roughly 8. 8%, down from 26% in 2022, due to restrictions on the H20 and other China-specific chips. Yet, this decoupling offers no protection against a blockade. The loss of the Chinese market is a regulatory certainty; the loss of Taiwan is an existential manufacturing emergency. The October 2025 market sell-off, triggered by renewed tariff threats, demonstrated the extreme sensitivity of Nvidia’s stock to geopolitical friction. A physical blockade would not be a pricing adjustment; it would be a revenue deletion event.

“The manufacturing of the most serious single chip at TSMC’s most advanced U. S. fab is a in recent American history… the entire supply chain necessary be built in the United States.”

, Jensen Huang, CEO of Nvidia, October 17, 2025

While Huang’s statement frames the Arizona production as a triumph of resilience, the operational reality is far starker. The cost of manufacturing in Arizona remains approximately 30% higher than in Taiwan, a premium Nvidia can absorb only because of its gross margins. yet, money cannot buy time. If the Taiwan Strait closes in mid-2026, the “entire supply chain” Huang referenced still be years away from the capacity required to replace the Taichung and Tainan gigafabs. The Nvidia exposure is not a future risk; it is a present-day liability valued at nearly $4 trillion, held hostage by the geography of a single island.

Cyber Espionage Vectors: State-Sponsored Attacks on IP and Fab Infrastructure

The “Silicon Shield” theory has collapsed into a security paradox: the very centrality of semiconductor manufacturing to global defense has transformed fabs from protected assets into primary for state-sponsored cyber warfare. Between 2022 and 2025, the semiconductor sector witnessed a 600% surge in cyberattacks, driven not by random criminal opportunism by coordinated espionage campaigns aligned with national strategic goals. This escalation has shifted the threat from passive intellectual property (IP) theft to active operational technology (OT) sabotage and pre-silicon hardware compromise.

Intelligence reports from late 2025 confirm that the convergence of IT and OT networks remains the industry’s most serious vulnerability. Over 60% of industrial control system (ICS) breaches in semiconductor fabs originate from initial compromises in corporate IT environments, allowing attackers to pivot from email servers to lithography control systems. The financial toll is: confirmed ransomware-related losses in the sector exceeded $1. 05 billion between 2018 and 2025, a figure that excludes the incalculable long-term cost of stolen proprietary designs.

The China Nexus: APT41 and the Chimera Campaigns

Chinese state-sponsored groups remain the most persistent aggressors, employing “living-off-the-land” techniques to evade detection while exfiltrating terabytes of lithography and design data. The Chimera group (also tracked as distinct elements of APT41) has demonstrated a sophisticated understanding of the semiconductor supply chain, targeting not just major foundries the obscure upstream suppliers that service them.

In July 2025, Taiwan’s National Communications and Cyber Security Center confirmed a massive infiltration by APT41 into at least six Taiwanese semiconductor organizations. The attackers utilized a compromised software update for a widely used industrial control application to bypass perimeter defenses. Once inside, they deployed cross-platform backdoors to harvest credentials and exfiltrate hundreds of gigabytes of process data over several weeks, blending their traffic with legitimate encrypted cloud services.

| Date | Target / Victim | Attributed Actor | Attack Vector | Strategic Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| July 2025 | Taiwanese Fabs & Designers | APT41 (China) | Compromised ICS Software Update | Theft of advanced process node data; 6+ firms breached. |

| Nov 2024 , Apr 2025 | South Korean Memory Mfrs | Lazarus (North Korea) | Operation SyncHole / Zero-Day | Lateral movement via “Innorix Agent” flaw; theft of yield data. |

| June 2023 | TSMC (via Kinmax Tech) | LockBit (Russia-linked) | Supply Chain / Ransomware | $70M ransom demand; exposure of server configuration setups. |

| Feb 2023 | Applied Materials | Mattson (China-owned) | Insider Threat / IP Theft | Lawsuit over theft of plasma etching trade secrets. |

| Feb 2022 | NVIDIA | Lapsus$ | Credential Stuffing | 1TB data theft including LHR source code and signing certificates. |

North Korea’s “Operation SyncHole”

North Korean actors, specifically the Lazarus Group, have pivoted from financial theft to strategic technology acquisition. In a campaign Operation SyncHole (November 2024 , April 2025), Lazarus operatives targeted South Korean semiconductor manufacturing and telecommunications firms. Unlike previous “smash and grab” operations, this campaign displayed high technical discipline.

The attackers exploited a zero-day vulnerability in Innorix Agent, a secure file transfer tool mandated by South Korean financial and industrial conglomerates. By compromising this trusted pathway, Lazarus moved laterally across air-gapped networks to access yield data and chemical formulas essential for memory chip production. This operation highlights a serious evolution: state actors are weaponizing the very security tools designed to protect IP.

The OT Sabotage Threat: Beyond Data Theft

The most worrying development is the shift toward Operational Technology (OT) disruption. The 2023 ransomware attack on MKS Instruments served as a bellwether event. While not explicitly attributed to a state mandate, the attack crippled the vacuum gauge supply chain, costing Applied Materials an estimated $250 million in a single quarter. It demonstrated that crippling a sub-tier supplier could halt production at major fabs globally.

More insidious is the emergence of AI-generated hardware Trojans. A 2025 CloudSEK report detailed a proof-of-concept where AI tools were used to design hardware implants at the pre-silicon stage. These microscopic alterations, invisible to standard optical inspection, can remain dormant for years until triggered to leak cryptographic keys or induce thermal failure. This “time-bomb” capability represents the violation of the semiconductor trust anchor.

Insider Threats and the “Human Vector”

even with advanced digital defenses, the human element remains a primary vector. In early 2023, ASML disclosed that a former employee in China had misappropriated data related to its proprietary lithography technology. Subsequent investigations linked the individual to Huawei, the blurred lines between corporate employment and state-directed industrial espionage. Similarly, Applied Materials has been embroiled in legal battles against Chinese-owned competitors accused of systematically poaching engineers to transfer plasma etching trade secrets, a “brain drain” strategy that bypasses export controls.

The Talent Deficit: Quantifying the Engineer absence in US Onshoring Efforts

The strategic ambition to reshore semiconductor manufacturing faces a formidable, non-silicon barrier: a severe and widening deficit of human capital. While the CHIPS Act provides the financial scaffolding for new fabrication plants, the United States absence the specialized workforce required to operate them. Data from 2023 through 2025 reveals that the construction of physical infrastructure has outpaced the development of the intellectual infrastructure necessary to run it, creating a bottleneck that capital investment alone cannot clear.

According to a 2023 report by the Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA) and Oxford Economics, the U. S. semiconductor industry faces a projected shortfall of 67, 000 workers by 2030. This gap includes technicians, computer scientists, and engineers, with the absence of design and manufacturing engineers being particularly acute. A subsequent analysis by McKinsey in August 2024 painted an even starker picture, estimating the chance talent gap could reach between 59, 000 and 146, 000 workers by 2029. The between supply and demand is structural; McKinsey noted that while the industry requires approximately 88, 000 new engineers by 2029, current graduation trends suggest only about 1, 500 qualified engineers join the semiconductor sector annually.

| Metric | Projected Need (2029-2030) | Current Annual Inflow | Projected Deficit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Engineers | 88, 000 | ~1, 500 | High Criticality |

| Technicians | 75, 000 | ~1, 000 | Severe absence |

| Total Workforce Gap | N/A | N/A | 67, 000, 146, 000 |

The operational consequences of this deficit are already visible in the delays flagship projects. TSMC’s Fab 21 in Arizona, originally scheduled to begin mass production of 4nm chips in 2024, pushed its timeline to 2025. Company leadership explicitly an “insufficient amount of skilled workers with the specialized expertise required for equipment installation” as the primary cause. To mitigate this, TSMC was forced to fly in hundreds of technicians from Taiwan, a move that sparked friction with local labor unions and highlighted the absence of domestic capability. Similarly, Intel’s massive Ohio “Silicon Heartland” project faced significant headwinds; by early 2025, reports indicated that production timelines had slipped toward 2030-2031, with workforce availability alongside market conditions as a complicating factor.

The root of the problem lies deep within the U. S. educational and immigration pipelines. National Science Foundation (NSF) that foreign nationals comprise approximately 74% of full-time graduate students in electrical engineering and 72% in computer and information sciences at U. S. universities. While these students represent a important talent pool, the U. S. immigration system creates significant friction in retaining them. The H-1B visa cap, which has remained stagnant for decades, results in a lottery system where selection rates have dropped 20%, forcing highly trained graduates to leave the country or seek employment in nations with more streamlined immigration pathways.

also, the semiconductor industry fights a losing battle for domestic talent against the software sector. “Big Tech” firms, Google, Meta, and Amazon, offer compensation packages that significantly outstrip those available in hardware engineering. A 2024 analysis of salary data showed that entry-level software engineers in major tech hubs could command salaries 30% to 50% higher than their counterparts in semiconductor process engineering. This diverts the limited pool of U. S. graduates away from the “hard tech” of fabs and into software development, leaving the physical of the digital economy dangerously understaffed.

The absence of technicians, the workers who maintain the complex lithography and etching tools, is equally damaging. Unlike design roles that require advanced degrees, technician roles require two-year degrees or certifications. Yet, enrollment in these vocational programs has not kept pace with the demand generated by the CHIPS Act. The 43% decline in the U. S. semiconductor manufacturing workforce since its peak in 2000 has eroded the institutional knowledge base, meaning new hires absence the mentorship of experienced veterans. Without a rapid and massive scaling of workforce development programs, the new fabs in Arizona, Ohio, and Texas risk becoming shells, unable to run at the capacity required to alter the global balance of power.

Global GDP Impact Modeling: The Ten Trillion Dollar Cost of a Taiwan Strait emergency

By February 2026, the economic calculus of a Taiwan Strait conflict has shifted from theoretical wargaming to urgent financial forecasting. New modeling from Bloomberg Economics, released earlier this month, quantifies the price of a full- invasion at approximately $10. 6 trillion. This figure represents roughly 10 percent of global GDP, a contraction that dwarfs the economic of the 2008 Global Financial emergency and the COVID-19 pandemic combined. The data dispels any lingering notion that a “localized” conflict in East Asia would remain contained. Instead, the integration of Taiwan’s semiconductor industry into the planetary digital infrastructure ensures that a kinetic event triggers an immediate, synchronized global depression.

The severity of this projection from the dual shock of supply chain amputation and maritime trade paralysis. Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) produces over 90 percent of the world’s most advanced logic chips. In a war scenario, these foundries would likely be rendered inoperable by sabotage, kinetic strikes, or power grid failures. Simultaneously, the Taiwan Strait, a waterway through which $2. 45 trillion in commercial shipping transits annually, would become a war zone, forcing global freight to reroute or halt entirely. The convergence of these factors creates a “Silicon Freeze,” where industries ranging from automotive manufacturing to data center construction face an immediate cessation of input materials.

Scenario Analysis: Blockade vs. Invasion

Economists distinguish between two primary escalation pathways: a maritime blockade (quarantine) and a full amphibious invasion. While a blockade is frequently discussed as a “lower intensity” option, the financial damage remains catastrophic. A blockade that cuts Taiwan off from global trade for one year would slash global GDP by approximately 5 percent. Under this scenario, Taiwan’s economy would contract by over 12 percent, while the United States and China would see GDP declines of 3. 3 percent and 8. 9 percent, respectively. The asymmetry in damage highlights a serious strategic reality: while Taiwan suffers most acutely, the aggressor, China, faces economic ruin nearly three times as severe as the United States in percentage terms.

The invasion scenario amplifies these losses exponentially. The following table details the projected -year GDP impact on major economies in the event of high-intensity combat, based on the February 2026 consensus data.

| Economy | Projected GDP Decline (%) | Primary Economic Driver of Loss |

|---|---|---|

| Taiwan | -40. 0% | Physical destruction, total trade cessation, capital flight. |

| South Korea | -23. 3% | Supply chain proximity, shipping disruptions, semiconductor market shock. |

| China | -16. 7% | Sanctions, loss of export markets, cessation of tech imports. |

| Japan | -13. 5% | Energy import blockade, regional trade collapse, defense mobilization. |

| Global Average | -10. 2% | widespread financial contagion, manufacturing halts. |

| United States | -6. 7% | Tech sector paralysis, financial market crash (Apple, Nvidia exposure). |

The Semiconductor Multiplier Effect