Thought leadership in public relations (PR) refers to positioning individuals or organizations as authoritative experts on a topic, using strategic content and media outreach to shape public opinion. Academics define it as “knowledge from a trusted, eminent, and authoritative source that is actionable and provides valuable solutions for stakeholders”.

In practice, PR firms help executives publish articles, speak at events, or produce white papers intended to influence target audiences. The goal is often brand-building or market positioning, rather than reporting news. As one PR professional notes, maintaining credibility is crucial: “My reputation is my currency. I have to sleep at night. I do a damn good job building and maintaining reputation by telling the truth”.

However, the boundary between genuine expertise and marketing can blur. By ghostwriting op-eds or disguising sponsored content as independent analysis, PR-driven thought leadership can mislead. For example, media watchdogs have exposed ghostwritten opinion pieces run under the bylines of high-profile figures (such as former politicians) to advance industry agendas.

Dan Gillmor of The Guardian noted that op-eds attributed to celebrities or leaders are “almost never written by those people”. Such tactics—where PR professionals craft content under a thought leader’s name—raise ethical concerns about transparency.

Figure: A corporate press conference in 2018 (Shazad Latif, Timur Bekmambetov, and Valene Kane) illustrates how media events are used to convey thought leadership. PR teams often stage such events to project expertise and authority. The effectiveness of these events depends on authentic messaging and factual accuracy.

In summary, thought leadership in media relations encompasses the deliberate creation and dissemination of expert content. When done responsibly, it informs and educates. But industry critics warn that it can become a vehicle for corporate spin if not clearly disclosed. The PR industry’s own code emphasizes honesty: “We have a duty of transparency,” says a UK PR expert, and “the future of public relations hinges on our ability to safeguard authenticity and ensure the stories we share remain free from misinformation and false narratives”.

Global Industry Practices and Key Players

Public relations firms worldwide offer thought leadership services. Large agencies like Edelman, Weber Shandwick (WPP), FleishmanHillard, and Burson-Marsteller (now BCW) run global campaigns for tech, healthcare, energy and other sectors. In the tech industry, agencies pitch CEOs and engineers as experts on emerging trends (AI, cybersecurity, etc.) to media and social channels.

Technology companies from Silicon Valley to Asia hire thought-leadership agencies to differentiate in crowded markets. For example, tech PR firms advise clients to “participate in conversations” about AI or blockchain on social media and industry events, aligning messaging with company goals.

In healthcare and life sciences, pharmaceutical and biotech companies promote their scientists or executives as authorities on medical innovation. They sponsor white papers or expert panels to build trust. (Historically, tobacco and pharmaceutical industries have faced criticism for using sponsored “product defense” research to mislead regulators.)

In recent years, health companies also collaborated with fact-checkers to counter Covid-19 misinformation. Global consultancies like Edelman and FleishmanHillard now publish medical PR surveys and host webinars on “health communication leadership.”

The politics and public affairs realm is another major arena. Governments and politicians deploy thought leadership by briefing senior officials with briefing papers or having them write op-eds on policy. Consulting firms (sometimes spun out of PR agencies) may advise political figures on communication strategy. In many countries, former journalists or ex-officials are hired to front think-tanks or “astroturf” groups.

The U.S. political consulting industry, for instance, spawned firms like Definers Public Affairs – a spin-off involved in high-profile campaigns. Definers was exposed in 2018 for distributing a “research” dossier tying critic George Soros to opposition groups, a tactic one watchdog called a “deliberate strategy to distract” from Facebook scandals. These examples show how “thought leadership” can blur into partisan influence.

In finance and corporate sectors, CEOs and economists publish forecast reports or opinion essays to influence markets and regulators. Conferences like the World Economic Forum now consider executive panels part of “brand thought leadership.” Corporate PR departments staff these efforts, but they often engage consultants.

The chairman of a major bank might co-author a paper on fintech adoption, syndicated by PR. Across industries, though names and targets differ, the technique is similar: create the appearance of an independent authority shaping the conversation on behalf of the client.

Globally, firms known for PR and thought leadership include Edelman, which publishes the annual Edelman Trust Barometer (framing itself as a “harbinger of trust” while serving clients in energy and pharma); UK’s Profile (specializing in tech and B2B thought leadership); and boutique agencies like Contented.io (tech PR), Purpose (public affairs), and Germ (industrial PR).

Individual consultants—such as retired business executives turned speakers or consultants—also serve as de facto thought leaders. However, verified data on the market size for “thought leadership services” is scarce; PR expenditures overall totaled over $20 billion globally (PRWeek’s 2022 estimates), with a significant slice for reputation and content strategies.

Regional and Comparative Perspectives

United States

The U.S. is the largest PR market and often sets global trends. American companies, from Big Tech to Wall Street, heavily use thought leadership to shape media narratives. Major universities and think tanks also blur into this, as corporate-funded research (e.g. on climate or economics) is circulated via press releases.

For instance, Edelman (U.S.-based) markets itself on a “Trust” platform, yet critics note its extensive work for polluting clients. Former Edelman insider Christine Arena testified before Congress that PR campaigns had blocked climate legislation, highlighting the US industry’s influence on public debate.

U.S. media relations often leverage the 24-hour news cycle. PR teams pitch op-eds, arrange speaking spots on cable networks, and engage influencers. There is growing scrutiny: after 2016-2020 political misinformation crises, platforms like Facebook began publishing “disinformation operations” ties.

A BuzzFeed News analysis found at least 27 disinformation campaigns linked to PR/marketing firms since 2011, with 19 in 2019 alone. These were mostly election-related, but not exclusively. U.S. regulators rely on disclosure laws: the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) requires influencers to label ads, and Section 230 shields platforms. Still, enforcement gaps exist, and the US Congress has debated fact-checking mandates without resolution.

United Kingdom

The UK has a robust PR industry and comparable ethical expectations. UK agencies and PR consultancies emphasize transparency; the Chartered Institute of Public Relations (CIPR) code mandates honesty. The Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) actively enforces sponsored content rules. In one notable crackdown, the ASA found that only about 35% of influencer posts clearly labeled paid promotions.

ASA CEO Guy Parker warned influencers that “there’s simply no excuse not to make clear when positive messages in posts have been paid for”. This highlights UK regulators’ view that undisclosed “thought leadership” content is essentially covert advertising.

British media relations often involve “commissioning pieces” in outlets or running sponsored supplements. The UK’s Online Safety Act (2023) explicitly addresses misinformation: it requires Ofcom to create an advisory committee on disinformation and mandates swift takedown of illegal content.

Though primarily aimed at tech platforms, it signals a national stance: misinformation in political PR could invite sanctions. The UK also experienced cases like the Definers PR saga with Facebook (though Facebook is US-based), illustrating cross-border PR influence. Cambridge Analytica’s misuse of data in UK and US elections also underscores the global nature of influence operations.

India

India’s media relations market is fast-growing but less centralized. Indian corporates (technology conglomerates like Tata, Infosys; pharmaceuticals like Sun Pharma, Serum Institute; and political parties) utilize thought leadership to varying degrees. Leading Indian PR firms (Adfactors, Genesis BCW) encourage CEOs to speak at conferences and write for media.

However, India is also grappling with rampant misinformation on social media (notably on WhatsApp) around elections and health issues. In response, the government has proposed stricter media regulations (including recently withdrawn draft rules on digital news).

The Press Council of India issues advisory guidelines on fake news. In 2024, India’s Election Commission launched a fact-check portal, acknowledging that “misinformation is a threat” during campaigns. Though specific “thought leadership” scandals are less documented, Indian media reported explosive rumors during elections (e.g. false claims about Muslim politicians, or Covid cures) that originated in partisan PR or social networks, echoing the Brazil scenario.

Other Regions

Europe (EU): The European Union requires member states to combat disinformation. Voluntary codes (Code of Practice on Disinformation) push tech platforms to monitor viral lies. Several countries (e.g. Germany, France, Sweden) have laws against hate speech and recently against deepfakes or foreign misinformation.

In these markets, corporate PR often brands policies (for example, German energy companies promoting “sustainability leadership”). However, regulators are also watching “dark ads” and hidden propaganda. PR associations in EU countries have ethics codes, but enforcement is mainly via national advertising laws.

East Asia: In China, media relations are tightly controlled by the state. “Thought leadership” takes the form of official spokespersons or Communist Party-sponsored experts, and foreign PR firms often work indirectly. Misinformation can flow from state narratives (e.g., on public health or technology).

In Japan and South Korea, PR is professionalizing rapidly; influencer marketing and corporate commentary on tech are growing. Governments there have also cracked down on misinformation: Japan passed an “Information and Communications” law in 2023 requiring social media firms to cooperate on disinfo.

Latin America: Brazil, Mexico and others have seen intense online campaigns. The 2022 Brazilian election saw a barrage of false claims via WhatsApp and YouTube. Brazil’s top court intervened to ban “false or seriously decontextualized” content during elections.

In Mexico, presidential campaigns have used PR firms to release viral memes. Across Latin America, lack of strict oversight means thought leadership content can easily slip into disinformation. However, some governments (Peru, Chile) now fund fact-checking NGOs and social media audits.

- Africa: Countries like Kenya, Nigeria, and South Africa have experienced social media rumors affecting elections. Some PR consultancies in Africa are international branches of UK/US firms. African governments are starting to legislate (e.g. Kenya’s anti-fake news law) and platforms like Facebook have partnered with local fact-checkers.

Overall, thought leadership in media relations is a global phenomenon with local flavors. In each region, cultural attitudes toward media and the strength of legal norms shape whether PR-driven content is expected to be transparent or can edge into propaganda.

Ethical Standards and Regulatory Challenges

As thought leadership blurs advertising and journalism, regulators and professional bodies grapple with ethics. The Public Relations Society of America (PRSA) code emphasizes honesty and disclosure. One PRSA-accredited practitioner notes, “I have to build reputation by telling the truth”. The CIPR in the UK likewise stresses integrity.

Yet social media influencers (often treated as modern thought leaders) frequently run afoul of guidelines. Both the FTC (US) and ASA (UK) require any paid or gifted endorsement to be clearly disclosed as advertising. UK ASA enforcement (see above) shows regulators will penalize breaches. The US FTC issued updated “Endorsements Guidelines” clarifying how bloggers and social media personalities must label content.

Despite this, enforcement is tricky. Influencers sometimes ignore rules, and thousands of posts evade oversight. The ASA in 2024 reported over 3,500 influencer-related complaints, indicating the volume of paid content slipping through.

The trend concerns PR professionals: as Silverman noted, some PR firms “self-describe” as agencies while running covert campaigns of fake followers and bots to create a false “groundswell” of support. These tactics can undermine honest thought leadership and fuel misinformation. In a 2025 survey, PR experts warned that lack of transparency in digital influencer content is “erosion of trust” for the entire industry.

Another challenge is the rapid rise of AI. PR firms now use AI tools to draft blog posts, social media updates and even news releases. Without oversight, AI-generated content can inadvertently recycle false information. Industry associations are debating guidance, but formal regulation lags.

Some scholars warn that AI could create “deepfake news releases” or automate disinformation campaigns for hire. This heightens calls for PR professionals to adhere to ethics codes: as one UK communications professional put it, “we must safeguard authenticity” by rigorous sourcing and fact-checking in every message.

At the governmental level, many countries see thought leadership as potentially manipulative if undeclared. Beyond platform rules, new laws are emerging. For example, the UK’s Online Safety Act (2023) includes measures to combat harmful misinformation, especially state-sponsored content.

China uses censorship to prevent certain narratives altogether. India and others have criminal penalties for spreading “fake news” that incites panic. These laws often intersect with PR: e.g., a CEO’s misleading claim about a vaccine could technically violate public health laws.

Internationally, though, there is no single framework for PR ethics enforcement. Instead, industry coalitions (Global Alliance for PR and Communication Management) and media organizations collaborate on voluntary standards.

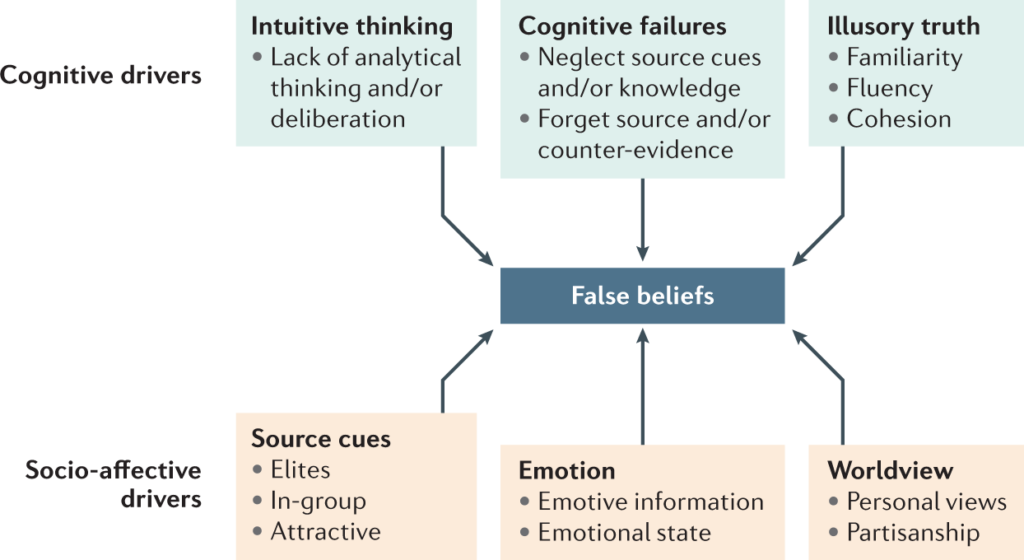

Figure: An infographic distinguishes “misinformation” (unintentional falsehoods) from “disinformation” (deliberate lies). Thought leadership campaigns can slip into either category. Ethical PR practice requires labeling sponsored content and refraining from willful deception.

Case Studies: When Thought Leadership Goes Wrong

Disinformation Campaigns and Astroturfing

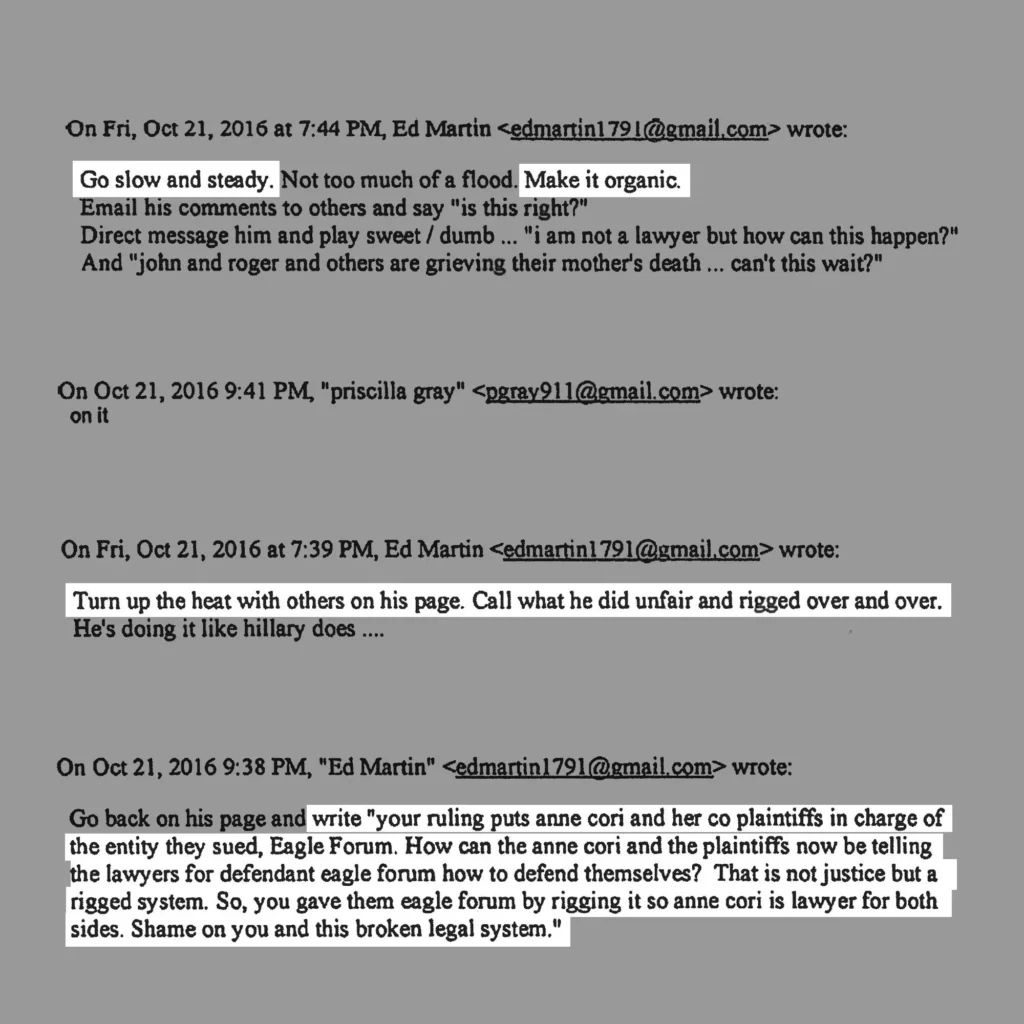

One of the most vivid examples of PR misdeeds is the political troll campaign in Illinois. In 2016, pro-life attorney Ed Martin orchestrated a conspiracy-laden social media blitz against a federal judge overseeing a local corruption case. It began innocuously with Martin’s friend Priscilla Gray writing a blog post attacking the judge.

Martin then ghostwrote dozens more social media posts and comments, coaching Gray on how to make them appear “organic,” e.g. advising her to “Go slow and steady… call what he did unfair and rigged”.

These messages falsely accused the judge of bias to sway public opinion. The campaign was exposed by ProPublica and Politico in 2025. Investigators called Martin’s tactics “particularly egregious,” noting he was a practicing lawyer and a Republican official. Martin faced legal sanctions, including disbarment hearings and over $600,000 in settlements.

This case illustrates a misuse of PR tactics: an overt propaganda effort masquerading as grassroots outrage. It also shows how thought leadership in media relations can morph into harassment. Martin’s actions were not labeled advertising or expert commentary; they were designed to poison public discourse.

The fallout included official condemnation and a public discussion about accountability. Legal scholars observed that this scheme violated ethical norms of both law and communications. Although not a commercial PR campaign, the Martin incident highlights how media manipulation expertise can be weaponized in politics.

Corporate Astroturfing

In the energy sector, Western States Petroleum Association (WSPA) offers a textbook case of covert PR. WSPA created and funded over a dozen front groups (like “California Drivers Alliance” and “Consumers for Clean Air”) that appeared to be grassroots coalitions opposing climate policies.

The Union of Concerned Scientists reported that WSPA used these “astroturf” organizations to publish op-eds, mobilize public comments, and confuse media about environmental legislation. All the while, big oil companies covertly bankrolled the effort. The strategy’s objective was clear: shape public debate on carbon taxes and regulations by feigning broader public opposition.

When journalists investigated in 2015-2017, outlets exposed the deception. Politicians and regulators who had seen these coalitions lobbying for them discovered their real sponsors. Public outrage ensued and some bills stalled. This scandal underscores how thought leadership tools (reports, talking points, media pitches) can be exploited.

Instead of transparent expert analysis, corporate PR can manufacture consent. It also raised ethical questions: editing Wikipedia entries or buying social media ads in favor of policy were commonly reported tactics. In short, WSPA’s case showed that when PR crosses into deception, it becomes “fake thought leadership,” eroding trust in both industry and media.

Social Media Influence Operations

Not all misuses occur behind closed doors. In the 2018 US midterms and Brazil’s 2018-2022 elections, pseudonymous social media accounts behaved as if led by passionate citizens but were actually run by organized teams. In the Philippines, online “troll farms” have been openly profiled in documentariesbbc.com. One BBC report described networks of young people paid to run hundreds of fake accounts, pumping out pro-government messages and harassing critics. Though these Philippines operations are political, they bear lessons for global PR ethics: agencies hired by politicians or businesses can similarly generate artificial consensus online.

Likewise, in India and other countries, WhatsApp groups and Telegram channels have been used by PR operatives to forward viral hoaxes. For example, in 2017-2018 India, fake news about child kidnappers and religious conspiracies spread on messaging apps and led to vigilante violence. Several media investigations linked some rumors to political insiders. While direct proof of PR firm involvement was scarce, analysts noted that such campaigns exhibit the same patterns: rapid amplification, motor-driven account networks, and indistinguishable content from legitimate news. The takeaway is that thought leadership content, if not clearly authored, can fuel “organic-looking” disinformation.

Industry-Specific Scandals

- Technology PR and News Media: Occasionally tech companies sponsor seemingly independent content. For instance, controversies have arisen when major tech firms funded “journalistic” projects without disclosure. In 2014, the New York Times paused collaboration with Google funding after ethical objections. Though not strictly “thought leadership,” it shows overlap: paid content posing as news. Tech PR agencies also face crises when products fail (e.g. Facebook’s Cambridge Analytica scandal led to intense scrutiny of their external messaging).

- Healthcare and Pharma: The pharmaceutical industry’s history of ghostwritten medical studies and disguised lobbying is well-documented. PR firms for drug companies once paid doctors to publish favorable papers, an ethical violation exposed in U.S. Senate hearings. In another case, Merck’s paid blogging about a controversial drug (Vioxx) was revealed to be written by PR agents, prompting journal retractions. These episodes taught that “thought leadership” (expert medical opinion) must not be masqueraded by marketing agendas.

- Corporate and Environmental PR: Apart from fossil fuels, industries like tobacco, pesticide and food have used thought-leadership tactics. For example, chemical firms have hosted “educational” conferences on pesticide safety led by third-party scientists who were actually funded by industry. Such “educational outreach” was later exposed by journalists as astroturfing. These serve as cautionary tales that any PR message, even if expert-sounding, should be scrutinized for hidden sponsors.

Figure: Excerpt from a 2016 email in the Illinois judge case (Ed Martin ghostwriting for Priscilla Gray). The highlighted lines show Martin coaching Gray to make attack posts seem “organic,” reflecting how behind-the-scenes PR scripting can mislead the public.

Expert and Professional Perspectives

PR professionals and media experts themselves acknowledge the dilemma. Professor David Olusoga (a historian and former BBC broadcaster) told industry leaders that the pandemic’s “greatest legacy” may be the erosion of truth, warning that we now live in a “far more troubling” era of mistrust. He urged communicators not to treat “post-truth” as destiny but to actively rebuild trust. Similarly, PR consultant Lateefah Jean-Baptiste emphasizes that transparency is non-negotiable: “PR professionals play a vital role in safeguarding truth… we’ve seen how crucial it is… to prioritise credible sourcing and ethical storytelling. The future of public relations hinges on… ensuring the stories we share remain free from misinformation”.

Industry bodies call for self-regulation. The PR Council (US) and CIPR (UK) periodically update ethics guides. In practice, many agencies promise to label sponsored content. However, independent surveys show mixed compliance. For example, a Global Alliance study found only about one-third of firms have official policies on influencer content disclosure. A former CIPR chair noted that digital platforms have made PR more direct, but also warned that practitioners must avoid “bias and fiction” when promoting clients.

Legally, PR agencies are largely free from liability for clients’ misinformation, except in narrow cases (e.g. libel or fraud). But growing regulatory attention means some firms have started auditing their campaigns. After Facebook’s Definers scandal (2018), many PR firms instituted stricter review of “transparency of third-party research.” In political advising, US lobbyists now register campaign expenditures, and PR help to draft advertising for campaigns (like the EU Citizens’ initiative or UK referendum) must carry disclaimers. In all markets, the onus is shifting slightly: regulators and platforms expect both companies and agencies to ensure “paid content” isn’t fake.

One positive example comes from climate advocacy: in 2014, the Climate Disinformation Coalition (led by the Union of Concerned Scientists) publicly listed PR firms working for climate deniers. Under pressure, ten of the world’s largest PR firms (Weber Shandwick, Edelman, WPP’s agencies, etc.) pledged not to take on clients that reject climate science. This episode shows an industry largely policing itself in face of public scrutiny.

International Comparisons

Comparing countries reveals both common challenges and unique approaches. A survey of global consumers (Edelman Trust Barometer 2023) showed trust in “social media” was only 35% on average, versus 54% in traditional media. This indicates general wariness of content coming from social platforms (where PR-driven “thought pieces” often appear). In countries like the US and UK, established media often demand clear PR disclosures. In emerging markets, media may be more susceptible to taking paid content as legitimate news due to economic pressures. For example, some Southeast Asian outlets accepted “native ads” disguised as investigative reports from paying companies, until journalists exposed the practice.

Some nations have proactively educated the public: Finland, once plagued by Russian propaganda, launched media-literacy programs in schools. None specifically target thought leadership, but the goal is similar: train audiences to critically evaluate “expert” claims. International organizations (UNESCO, EU Commission) have also promoted guidelines for digital literacy, which implicitly apply to PR content. As one French regulator put it, “Every citizen should know that not every expert quoted in the media is independent.”

On the flip side, developing countries sometimes look to PR as a growth sector. India and China have thousands of PR startups, many focusing on social media influence – though official policy in China restricts foreign PR activities. Some African nations have contracted Western PR firms to “rebrand” governments or oil industries (Nigeria’s image campaigns, for instance). Here, thought leadership is state-driven, making independent verification difficult.

Conclusions: A Balanced View

Thought leadership in media relations is a powerful but double-edged tool. On one hand, it allows genuine experts to share insights and can elevate discussions (for example, tech CEOs explaining industry trends or doctors summarizing research). It can enhance public knowledge and trust when done ethically. On the other hand, every practice invites abuse. The line between credible leadership and strategic marketing is not always clear to audiences. Our investigation shows that transparency and accountability are the critical fault lines.

When PR agencies operate ethically—crediting authors, citing facts, and disclosing conflicts—thought leadership can be a positive force in media. But numerous case studies (from the Ed Martin disinformation ring to the WSPA astroturf campaign) warn that without vigilance, these practices can pollute public discourse. Regulatory frameworks are still catching up, and professional bodies must continue reinforcing ethical norms. As media evolves, readers and viewers too must become critical: who is speaking and why must always be questioned.

In sum, our deep dive across industries and countries reveals that thought leadership in media relations is ubiquitous and influential, yet fraught with ethical pitfalls. The future of this practice depends on a mix of self-regulation (by PR firms), oversight (by governments and platforms), and an informed public. As historian David Olusoga urged, communicators should not resign themselves to “post-truth” but strive to rebuild trust through responsible messaging.

Sources

- Jones, S., & Knight, J. “The tensions of defining and developing thought leadership” (2023)

- Gillmor, D. The Guardian (2011). “In a world of op-ed ghostwriting…”

- Parrot, T.V. PRSA PRsay. “Setting the Record Straight About the Ethical Practice of Public Relations”

- Union of Concerned Scientists (2017). “How Fossil Fuel Lobbyists Used ‘Astroturf’…”.

- Techdirt/ProPublica (2025). “The Untold Story of How Ed Martin Ghostwrote Online Attacks Against a Judge…”

- Silverman, C. & Craig Timberg. BuzzFeed News (2020). Interview: “Disinformation for Hire”

- Skaf, M. PRmoment (Feb 2025). “PR’s role in battling mistrust and misinformation”

- Sweney, M. The Guardian (Mar 2021). “UK social media influencers warned over ad rules”

- Media reports (Apr 2022). “Brazilian voters bombarded with misinformation before vote”

- BBC News (Sept 2020). “Philippines Troll Patrol:….”

- Edelman Trust Barometer Report (2023)

- Edelman / climate campaign analyses (2023)

- PRSA, ASA, FTC guidelines on endorsements and truthfulness