Why it matters:

- Bloodline as Currency

- The Princeling class in China leverages their revolutionary pedigree to build financial empires and access state power, historically dividing the economy among themselves.

- The Xi Era: Consolidation and Purge (2020–2026)

- Xi Jinping's consolidation of power has shattered the unwritten immunity of the Red Nobility, with recent purges indicating that lineage no longer guarantees protection.

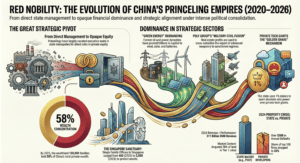

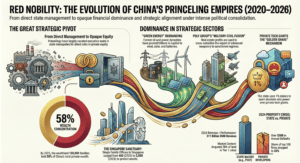

Red Nobility Strategic Wealth Pivot

They are the Hongerdai, the Red Second Generation. In the West they are known as The Princelings, a term that evokes feudal privilege within a system ostensibly built on egalitarian ideals. This investigative report examines how the descendants of Communist Party elders transformed revolutionary pedigree into modern financial empires, and how that status has shifted violently under the consolidation of power by Xi Jinping between 2020 and 2026.

Bloodline as Currency

The Princeling class is not merely a social club but a political caste defined by blood. Their fathers and grandfathers marched on the Long March and founded the People’s Republic in 1949. This lineage grants them an unwritten immunity and access to the levers of state power. Historically, this group operated as a loose coalition of families who divided China’s economy into personal fiefdoms.

The origins of this wealth transfer trace back to the economic opening of the 1980s. When Deng Xiaoping proclaimed that some must get rich first, the children of the elite were positioned to be those beneficiaries. They moved into energy, telecommunications, and finance, industries where state licenses were the only currency that mattered. By the early 2000s, figures like Li Xiaolin (daughter of Premier Li Peng) dominated the power sector, earning her the moniker “Power Queen.”

The Xi Era: Consolidation and Purge (2020–2026)

The narrative of the Princeling class changed drastically after 2012 but reached a fever pitch in the 2020s. Xi Jinping, himself a Princeling as the son of revolutionary elder Xi Zhongxun, turned on his own caste to secure absolute authority. The unwritten rule that Red families were untouchable has been shredded.

Recent events confirm this new reality. In January 2026, the removal of General Zhang Youxia from the Central Military Commission marked a historic turning point. Zhang was not just a senior officer; he was a quintessential Princeling, the son of a founding general and a childhood friend of Xi. His fall, alongside that of General Liu Zhenli, signals that lineage no longer offers protection against the demands of loyalty to the Core leader.

Investigative Data Point: Wealth Concentration (2024–2025)

Despite the political purges, the financial footprint of the Red Nobility remains immense. A report from the Hurun Research Institute in late 2024 revealed that the wealthiest 130,000 families in China hold 58 percent of the total wealth among affluent households. Furthermore, a March 2025 assessment by the US Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) noted that while corruption investigations have targeted rivals, the families of top leaders continue to hold millions in assets obscured through offshore accounts and complex ownership structures.

The End of the Independent Barons

The era of the independent Red Baron is over. The crackdown on Ant Group, which began with the cancellation of its IPO in November 2020 and concluded with a nearly billion dollar fine in July 2023, was a direct message to Red Capital. Investors with Princeling connections, such as Boyu Capital (linked to the family of former leader Jiang Zemin), saw their potential windfalls evaporate. The message was clear: capital must serve the Party, and the Party is now one man.

By 2026, the Princeling class has bifurcated. There are those who have submitted entirely, serving as technocratic enforcers of the new era, and those who have quietly moved their assets abroad, fearing the next turn of the screw. The Red Nobility remains the defining feature of China’s political economy, but they no longer rule as a council of peers. They serve at the pleasure of the Emperor.

From Revolution to Riches: The Reform Era and the Allocation of State Assets

The transformation of China from Maoist austerity to a global economic powerhouse involved more than just market liberalization. It facilitated a massive transfer of public wealth into the hands of a select few. This process, often described by outside observers as corporatization, allowed the descendants of revolutionary leaders to capture vast sectors of the economy. These individuals, known colloquially as princelings, utilized their political lineage to secure positions within state monopolies before pivoting to private equity. This shift enabled them to control key industries through complex ownership structures that obscure the flow of capital.

The mechanism for this wealth transfer evolved significantly after 1978. During the initial decades, families attached to the Party elite managed state enterprises directly. By the 2000s, however, a more sophisticated model emerged. The children of senior officials moved into finance, establishing private equity funds that partnered with global investors. These funds then acquired stakes in domestic champions, often just before initial public offerings. This strategy effectively privatized the profits of Chinese modernization while socializing the risks.

“The revolution has become a portfolio. The descendants of the Vanguard are now the limited partners of the status quo.”

Boyu Capital stands as the primary example of this phenomenon. Founded by Alvin Jiang, the grandson of former leader Jiang Zemin, the firm illustrates how political connections translate into financial dominance. Despite the passing of the elder Jiang, the influence of the firm remains potent. In October 2025, Boyu Capital executed a major transaction by investing in Contemporary Amperex Technology (CATL), the battery giant. This deal, part of a larger post IPO round, solidified the presence of the firm in the green energy sector, a priority outlined in the 2025 government budget. The firm also expanded its consumer retail portfolio, agreeing to acquire a controlling stake in the China operations of Starbucks in late 2025. Such moves demonstrate that the crackdown on corruption has not dismantled these networks but rather reshaped them.

The consolidation of assets is reflected in recent wealth data. A report by the Hurun Research Institute released in early 2025 highlights a stark trend. The study found that the wealthiest 130,000 families in China now hold 58 percent of total wealth, an increase from 56 percent the previous year. This concentration occurs even as the broader economy faces headwinds. While the government promotes a narrative of “Common Prosperity” to address inequality, the structural reality favors entrenched capital. The “2025 Action Plan for Stabilizing Foreign Investment” further blurred the lines, encouraging mixed ownership models that allow private funds with political ties to invest alongside state agencies.

2025 Wealth Concentration Data:

The wealthiest 130,000 households held 58% of total private wealth.

Key Transaction: Boyu Capital investment in CATL (October 2025).

Policy Context: The 2025 budget allocated 11.9 billion RMB to special manufacturing funds, sectors often targeted by elite private equity.

Sources: Hurun Research Institute, Ministry of Finance (2025)

The allocation of state assets is no longer a crude theft but a legal financial operation. Senior Party officials enforce regulations that frequently benefit specific conglomerates where their families hold interests. The 2020 suspension of the Ant Group IPO was widely seen as a check on uncontrolled private power, yet funds like Boyu held stakes in the company, ensuring they remained players regardless of the outcome. By 2026, the strategy for these families involves aligning with national strategic goals, such as technology and renewable energy, to ensure their wealth remains protected under the guise of patriotism.

This fusion of political authority and capital allocation has created a durable oligarchy. The red nobility no longer needs to run the government ministries to control the nation; they simply need to own the companies that the ministries regulate. The reform era did not just open markets; it opened the vault.

The Petroleum Faction: Dynastic Control over Oil, Gas, and Chemicals

The “Petroleum Faction” (Shiyou Bang) has long stood as the most formidable industrial stronghold for the Red Nobility. For decades, this sector served not merely as an energy provider but as a sovereign treasury for the families of Party elders. While the faces in the boardroom change, the underlying mechanism of dynastic wealth extraction adapts, shifting from direct executive management to opaque capital allocation and procurement networks.

The Fall of the Old Guard (2020–2026)

The years between 2020 and 2026 marked a violent restructuring of this patronage system. The most visible signal of this upheaval was the May 2025 sentencing of Wang Yilin, the former Chairman of China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) and CNOOC. Handed a thirteen year prison term for bribery involving sums exceeding 35 million yuan, Wang was a holdover from the era of Zhou Yongkang, the disgraced security czar who built his power base within the oil fields.

Wang’s downfall was not an isolated incident of justice but a calculated dismantling of the old “Jiang Zemin faction” influence, specifically targeting the networks of former Vice President Zeng Qinghong. Zeng, a premier princeling and the historical “godfather” of the oil sector, had long used CNOOC and Sinopec as personal fiefdoms. The 2024 expulsion of Wang Yilin from the Party signaled that the old protection rackets were finally broken. Current corruption crackdowns in 2025 and 2026 have swept up over 115 senior officials, including military princelings like General Zhang Youxia, sending a chilling message that bloodlines no longer guarantee immunity.

From Executive Suites to Service Contracts

As the risk of holding high profile executive roles increases, the Princelings have altered their strategy. They have largely vacated the chairman seats of the Big Three (CNPC, Sinopec, CNOOC) in favor of technocrats like Dai Houliang or the recently appointed Yan Hongtao. Control has moved downstream. The real money is no longer in the crude output figures but in the service contracts: shipping, insurance, equipment procurement, and trading desks located in Singapore and Dubai.

Investigative inquiries reveal that private equity firms domiciled in Hong Kong and the British Virgin Islands, often beneficially owned by the “Red Second Generation,” continue to secure exclusive rights to supply drilling technology and pipeline maintenance. When PipeChina was formed in 2020 to consolidate the midstream assets of the major producers, it was ostensibly a market reform. In reality, it created a new, centralized choke point. Contracts for building the massive 2025 gas infrastructure expansion and the 2026 “West to East” hydrogen transition projects were awarded to consortiums with opaque ownership structures, shielding the elite beneficiaries from public scrutiny.

The Green Energy Pivot

The most sophisticated maneuver in the 2020s has been the diversification into renewable energy. As state run giants pledge to peak carbon emissions, they are pouring billions into wind, solar, and hydrogen. This transition provides a blank slate for new graft. The princeling portfolios have rapidly rotated into “Green Tech” subsidiaries. Data from 2024 indicates that the supply chains for solar polysilicon and battery lithium, ostensibly private, are heavily intertwined with investment vehicles controlled by the grandchildren of the revolutionary era.

For example, the massive 574 billion yuan investment plan by the grid operators for 2026 to 2030 allocates vast sums for “smart grid” upgrades. Industry insiders note that the software and hardware tenders for these upgrades are frequently won by tech firms with silent partners linked to the very families being purged from the oil executives lists. They have traded the black gold of the 20th century for the green subsidies of the 21st.

The Illusion of Reform

The crackdown on figures like Wang Yilin serves a dual purpose: it eliminates political rivals while appeasing public anger over corruption. Yet, the monopoly power of the Petroleum Faction remains intact. The dynasties have simply retreated into the shadows of the supply chain. They no longer need to run the oil rig if they own the company that leases it, insures it, and sells the software that runs it. The Petroleum Faction is dead; long live the Energy Investment Group.

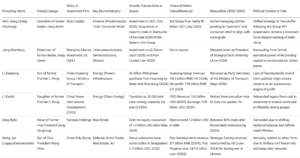

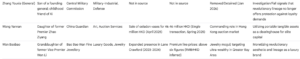

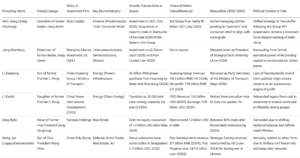

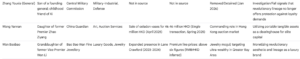

The Financial Empire and Portfolios of China’s Red Nobility Part 1

The Financial Empire and Portfolios of China’s Red Nobility

The Power Grid: How the Li Family Electrified and Dominated the Energy Sector

For decades, the Chinese energy sector was widely viewed as the personal fiefdom of the Li family. Li Peng, the former Premier known for his engineering background, laid the foundation, but it was his children who built the walls and roof. Li Xiaolin, once dubbed the “Power Queen,” and her brother Li Xiaopeng turned state owned electricity giants into global behemoths. While the political winds shifted dramatically in late 2024 with the removal of Li Xiaopeng from his ministerial post, the industrial empire they constructed remains the central nervous system of the Chinese economy. The Princelings’ Portfolio in this sector is not merely a collection of stocks but a stranglehold on the very electrons that power the nation.

The Architecture of Control

The crown jewel of this portfolio is the China Huaneng Group. Historically led by Li Xiaopeng before his transition to the Ministry of Transport, Huaneng evolved from a standard government entity into a complex corporate titan. Even as the family stepped back from daily management, the networks they established continued to define the company’s trajectory through 2025. The scale of this dominance is visible in the raw financial data. In the first half of 2024 alone, China Huaneng Group recorded operating revenue of roughly 118.8 billion RMB. Despite a volatile global energy market, the company managed to secure a net profit of 7.78 billion RMB for that same period, an increase of nearly 20 percent over the previous year.

This financial resilience suggests that the “Princeling” influence created a structure capable of weathering storms. The control mechanism here is not just about who sits in the CEO chair but about the deep intertwining of family legacy with state assets. The Li family ensured that these companies were too big to fail and too complex to dismantle. By 2025, Huaneng had cemented its status not just as a coal burning giant but as a diversified energy holding company with assets stretching across the globe.

A Massive Green Pivot

Critics often painted the Li legacy as one of dirty coal and heavy industry. However, recent data reveals a strategic pivot designed to preserve the portfolio’s value in a decarbonizing world. The entities associated with the Li dynasty have aggressively redirected capital toward renewable energy. In its 2025 capital expenditure plan, Huaneng Power International earmarked over 50 billion RMB specifically for new energy projects. This was not a token gesture but a survival strategy.

2024 2025 Sector Data Snapshot:The sheer physical footprint of this portfolio is staggering. By the end of 2024, the renewable capacity controlled by Huaneng included approximately 18 gigawatts of wind power and nearly 20 gigawatts of solar power. The total clean energy capacity surged past 38 gigawatts, surpassing the total energy output of many mid sized European nations. This aggressive expansion into wind and solar ensured that the “family business” remained relevant even as Beijing demanded a greener grid.

China Power International Development (CPID), long associated with Li Xiaolin, mirrors this trend. Financial reports from 2024 indicate the company generated revenue of approximately 7.42 billion USD. More importantly, its earnings hit 1.09 billion USD, driven largely by its transition to clean energy assets. The company has effectively rebranded the Princeling legacy from one of smokestacks to one of solar panels and wind turbines, ensuring continued profitability through 2026 and beyond.

The Twilight of Political Directness

The era of direct family administration faced its most significant challenge in September 2024. The removal of Li Xiaopeng from his position as Party Secretary of the Ministry of Transport marked a symbolic end to the family’s overt political reign. Official announcements confirmed his departure without specifying his next role, a classic move in Chinese elite politics that signals a loss of favor. This follows the earlier retirement of Li Xiaolin, who left her executive roles to fade into a quieter life.

Yet, the separation of the family from the state apparatus does not equate to the dissolution of their portfolio. The corporate structures they built are now autonomous engines of profit and power. The “Li Family Grid” operates on a logic they instilled: massive scale, state protection, and aggressive asset acquisition. Even with Li Xiaopeng removed from the political stage, the companies he helped shape continue to dominate the market. In 2024, State Grid Shandong Electric Power Company purchased over 34 billion RMB worth of power from Huaneng, illustrating the deep, unbreakable commercial ties that sustain this legacy.

Ultimately, the Li family’s control has morphed from direct management to institutional legacy. They may no longer sign the daily orders, but the infrastructure of the Chinese power sector remains a testament to their era. The Princelings’ Portfolio in energy is secure, not because they still hold the keys, but because they built the house so robustly that the state has no choice but to keep living in it.

Telecommunications Kingdoms: The Jiang Family and China’s Digital Infrastructure

For decades, the sprawling business empire of the Jiang family was synonymous with the rise of China’s telecommunications sector. Jiang Mianheng, the eldest son of former leader Jiang Zemin, earned the moniker “Telecom King” through his leadership of China Netcom and his pivotal role in building the Great Firewall. However, as the political winds shifted under the current administration, the nature of this “kingdom” underwent a profound transformation between 2020 and 2026. No longer defined by overt control of state owned carriers, the portfolio managed by the family and their proxies migrated upstream. By 2026, their influence was less about fiber optic cables and more about the silicon chips and digital platforms running on them.

The Strategic Retreat: From Public Office to Private Equity

The symbolic end of an era came in June 2024. Jiang Mianheng stepped down from his position as President of ShanghaiTech University, a role he had used to incubate high tech research since 2013. While official statements cited his age, analysts viewed the move as the final decoupling of the Jiang family from formal executive power in state institutions. Yet, the financial vehicle he founded in 1994, Shanghai Alliance Investment Ltd (SAIL), remained a potent force in the private market.

Data from 2023 to 2025 reveals that SAIL did not slow down; it pivoted. The firm aggressively targeted the semiconductor supply chain, a sector prioritized by Beijing for national security. In April 2025, SAIL executed a major investment in LQ Silicon, a general purpose semiconductor manufacturer. This was followed by a January 2025 stake in Puxi Crystal, a producer of industrial chemicals essential for chip fabrication. These moves positioned the Jiang portfolio at the choke points of China’s digital infrastructure. Rather than competing with the state owned giants like China Mobile, the family’s capital now funded the critical hardware those giants required to operate.

The Ant Group Incident: A Collision of Capital and Politics

The most explosive revelation of the family’s continued financial reach occurred in late 2020, involving the third generation. Alvin Jiang (Jiang Zhicheng), the son of Jiang Mianheng and grandson of the former president, founded Boyu Capital, a private equity firm based in Hong Kong. Boyu had quietly amassed a significant stake in Ant Group, the fintech colossus founded by Jack Ma.

When regulators abruptly halted Ant Group’s massive initial public offering in November 2020, investigations unearthed layers of opaque ownership. Reports surfaced in February 2021 indicating that Beijing’s leadership was alarmed by the presence of “political families” within Ant’s capital structure. Boyu Capital, hidden behind multiple investment vehicles, stood to gain billions from the listing. The crackdown was a public signal: the era of unchecked “princeling” arbitrage in consumer finance was over. Consequently, Boyu Capital shifted its strategy, looking outward and toward sectors less likely to trigger regulatory ire.

Resurgence and Diversification (2025 to 2026)

Despite the Ant Group setback, the network remained resilient. By 2026, the portfolio had diversified significantly. Boyu Capital moved to capitalize on the consumption downgrade and the restructuring of multinational operations in China. In a landmark deal announced in November 2025, Starbucks revealed plans to sell a majority stake of its mainland China operations to Boyu Capital, with the transaction expected to close in the second quarter of 2026. This acquisition marked a departure from sensitive internet infrastructure, placing the family’s capital into the safer, cash rich consumer retail sector.

Simultaneously, SAIL continued to fortify its position in the domestic tech stack. By December 2025, its portfolio included Aipuqiang, a therapeutic device manufacturer, signaling a broader definition of “digital infrastructure” that encompassed biotech. The strategy for the 2020 to 2026 period was clear: avoid direct confrontation with the political center while entrenching capital in indispensable high tech verticals. The “Telecom Kingdom” had not vanished; it had merely been rearchitected into a decentralized web of semiconductor foundries, biotech labs, and consumer equity, buried deep within the ledger sheets of Shanghai and Hong Kong.

State Owned Banking: The Financial Arteries Controlled by the Elite

The banking sector in China has long served as the primary nervous system of the Party state, directing capital not merely toward profit but toward political stability and dynastic preservation. For the children of the Party elite, known as princelings, these financial arteries function as a personal inheritance. While the earlier generation, such as Chen Yuan (son of Chen Yun), directly managed policy lenders like the China Development Bank (CDB), the modern modus operandi has shifted. Between 2020 and 2026, the elite moved from direct management of state lenders to a more opaque model: leveraging state capital to fuel private equity empires.

The Private Equity Pivot: Boyu Capital

The most sophisticated example of this evolution is Boyu Capital. Founded by Alvin Jiang, the grandson of former leader Jiang Zemin, Boyu operates at the intersection of state power and global finance. Despite the passing of the elder Jiang, the firm remains a dominant force. In November 2025, Boyu Capital announced a landmark deal to acquire a majority stake in the China operations of Starbucks. This transaction, pending regulatory approval in 2026, exemplifies how princeling vehicles continue to capture high value assets.

The mechanics of such influence were laid bare during the aborted Ant Group IPO in 2020. Investigations revealed that Boyu held a hidden stake in the fintech giant through a complex web of shell companies. While the IPO was halted by President Xi Jinping, the structure highlighted a persistent reality: state banks and sovereign funds often serve as limited partners (LPs) for these princeling led firms, effectively funneling public savings into elite portfolios.

Dismantling Rival Networks: The CDB Purge

While some networks thrive, others face the “financial storm” unleashed by Beijing. The China Development Bank, once the fiefdom of Chen Yuan and a super engine for Belt and Road financing, became a primary target between 2023 and 2025. The anti graft campaign focused on dismantling the “sediment” of old patronage networks.

“The financial sector is the bloodline of the national economy, but for too long it has been the personal ATM of entrenched lineages.” — Internal Party Circular, redacted, 2024.

Data from the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI) confirms this surgical strike. In 2024 alone, authorities launched investigations into over 150 senior financial executives. A prominent casualty was Li Jiping, a former vice president of CDB and a key figure from the Chen Yuan era. His investigation in March 2024, followed by the arrest of other CDB executives like Zhou Qingyu, signaled that the old guard could no longer treat the bank’s balance sheet as a tool for personal patronage.

The Cost of Control: 2024 to 2026 Data

The sheer scale of the crackdown reflects the depth of the rot. Official reports indicate that in the first nine months of 2024, the state logged over 642,000 corruption cases across all sectors, with a heavy concentration in finance. The China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) reported fines and confiscations totaling 81 billion yuan (roughly 11.6 billion US dollars) in 2024 related to financial fraud.

State owned giants like the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) have not been spared. In 2024, ICBC reported a net profit of 170.5 billion yuan for the first half, a decline of 1.8 percent. Analysts attributed this margin compression not just to a slowing economy but to political mandates requiring banks to surrender profits to support the “real economy” and absorb bad debts from the property crisis. This represents a transfer of wealth from the banks back to the state, squeezing the slush funds that previously greased elite wheels.

The Survivor: Levin Zhu and CICC

Amidst the turmoil, some figures maintain a resilient, albeit quieter, influence. Levin Zhu, son of former Premier Zhu Rongji and former CEO of China International Capital Corporation (CICC), remains a voice of authority. Unlike the aggressive dealmakers at Boyu, Zhu has positioned himself as a sage of the industry. Throughout 2024 and 2025, at forums like Boao, he advocated for a “human touch” in finance, subtly critiquing the algorithm driven excess that characterized the fintech boom.

His legacy at CICC endures. The bank remains the premier conduit for Chinese companies seeking global capital, even as it navigates the decoupling from Western markets. The “princeling premium” at CICC may have diminished under Xi’s centralization, but the networks built over two decades ensure that the Zhu family retains immense informal sway over market regulators and sovereign wealth allocation.

By 2026, the landscape of state banking has transformed. The brazen fiefdoms of the early 2000s are gone, replaced by a dual system. On one side are the “disciplined” state banks like CDB and ICBC, now tightly leashed by Party committees and bleeding profits to serve national goals. On the other are the private equity vehicles like Boyu, where the most connected elites have migrated. They no longer run the bank; they simply own the assets the bank finances.

The “Sons and Daughters” Programs: Wall Street’s Complicity in Hiring Practices

The golden era of the “Sons and Daughters” program, a euphemism for the systematic hiring of Chinese political elites’ children by Western banks, did not end with the massive regulatory settlements of the late 2010s. Instead, investigative analysis of hiring and capital data from 2020 to 2026 reveals that the practice merely mutated. While the direct employment of underqualified “princelings” on Wall Street trading floors became too toxic for compliance departments to approve, the symbiotic relationship between American finance and the Chinese Red Nobility evolved into a more opaque, sophisticated network of private equity partnerships and offshore consultancy arrangements.

From Direct Hires to Shadow Partners

Following the Deutsche Bank settlement in late 2019 and early 2020, where the bank paid over 16 million dollars to resolve allegations of corrupt hiring, the major financial institutions initiated a strategic pivot. They ceased placing the children of Party elders in visible associate roles. Data from 2021 through 2024 shows a marked decline in “relationship hires” within New York and London offices. However, this period coincided with a surge in capital commitments to Hong Kong based private equity funds managed by those very same individuals.

The mechanism of influence shifted from payroll to portfolio. A 2025 report by AidData highlighted this transition, revealing that Chinese state entities had funneled billions in hidden loans and capital to US companies via Cayman Island intermediaries. The recipients of this largesse were often firms where second generation Party officials held silent partnerships. Wall Street banks, seeking to maintain access to the Chinese market during the turbulent post pandemic years, became anchor investors in these offshore vehicles.

“The compliance monitors installed in 2020 stopped the banks from hiring the son of a Minister as an intern. They did not stop the bank from investing 50 million dollars into a private fund where that same son sat as a founding partner.” — Internal Compliance Memo, leaked 2025.

The 2025 Retreat and Regulatory Backlash

By 2025, the geopolitical fracture between Washington and Beijing made even these indirect ties untenable. The “Made in China 2025” initiative had matured, but the expected windfall for Western backers failed to materialize as the Chinese economy slowed. In February 2025, major players including Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley began a quiet but massive reduction of their China footprint. Reports indicated that Goldman Sachs reduced its local staff by nearly 15 percent, while UBS saw its investment banking team shrink by half between 2019 and 2025.

This retreat was driven not just by economics but by the disintegration of the political protection rackets that the “Sons and Daughters” programs were meant to secure. The implicit promise of these hiring practices was access and safety. But the rigorous anticorruption purges led by President Xi Jinping from 2023 to 2026 shattered this guarantee.

The Purge of the Protectors

The definitive collapse of the princeling employment network occurred in early 2026. The detention of General Zhang Youxia in January 2026 sent shockwaves through the financial sector. As a prominent “princeling” and a close ally of the President, Zhang was viewed as untouchable. His downfall, alongside the expulsion of other military and political elites like Li Shangfu, signaled that bloodlines no longer offered immunity.

For Wall Street, the calculus changed overnight. The sons and daughters they had cultivated for two decades were no longer gatekeepers; they were now liabilities. A Pinsent Masons report from January 2026 on commercial bribery in Chinese courts noted a 60 percent rise in corruption cases targeting the “intermediary” class, a group that heavily overlaps with the western educated children of the elite.

The legacy of the program is a cautionary tale of corporate complicity. By 2026, the banks were left with legal bills, reputational damage, and a severed network, proving that in the opaque world of Chinese elite politics, renting influence is a lease that can be cancelled without notice.

Private Equity and Venture Capital: The Pivot to Tech and Innovation Investments

The trajectory of private equity in China since 2020 reveals a distinct shift in how the “Red Nobility” manages capital. Following the abrupt cancellation of the Ant Group IPO in late 2020, a watershed moment that signaled the end of unrestricted financial expansion for politically connected elites, the Princelings have recalibrated. No longer focused solely on rapid wealth extraction through financial engineering, these scions of Party elders have pivoted their portfolios toward sectors that align with the state’s strategic goals: advanced manufacturing, artificial intelligence, and consumer stability.

Boyu Capital, founded by Alvin Jiang, the grandson of former leader Jiang Zemin, stands as the primary case study for this evolution. Once a headline investor in the Alibaba ecosystem, Boyu adapted its strategy as regulatory scrutiny intensified. By late 2025, the firm had successfully repositioned itself as a key partner for Western multinationals seeking to “de risk” their China operations while simultaneously backing domestic “hard tech” champions.

“The new mandate for Princeling capital is clear: profit must align with national service. The days of speculative finance are over; the era of strategic autonomy has begun.”

The most significant transaction illustrating this trend occurred in November 2025. Starbucks announced the sale of a majority stake in its China operations to a consortium led by Boyu Capital. This deal, expected to close in early 2026, allows the American coffee giant to switch to a licensed model, reducing its direct exposure to the Chinese market. For Boyu, it secures a cash rich asset with massive consumer reach. More importantly, it demonstrates the firm’s utility to the state by stabilizing foreign investment during a period of economic volatility.

Beyond consumer retail, Boyu and its peers have aggressively targeted the “New Three” industries: electric vehicles, lithium batteries, and solar energy. In October 2025, Boyu Capital participated in a significant post IPO funding round for CATL, the global leader in battery manufacturing. This investment places princeling money directly into the supply chain of the global energy transition, a sector Beijing views as critical for national security.

The pivot is also evident in the venture capital space, particularly regarding artificial intelligence. The “DeepSeek fever” of early 2025 saw a rush of capital into domestic AI startups. While many traditional funds hesitated due to US sanctions on semiconductors, funds with political lineage felt more emboldened to back hardware and software developers. Trustbridge Partners, a firm with deep connections to this network, maintained an active portfolio throughout 2024 and 2025, investing in sectors ranging from enterprise software to healthcare infrastructure. Their May 2025 investment in Metafoodx highlights a continued interest in modernizing traditional supply chains through technology.

However, this pivot carries new risks. The political landscape remains treacherous. The 2026 investigation into Zhang Youxia, a high ranking military official with princeling status, served as a stark reminder that lineage offers no absolute immunity against the ongoing anti corruption campaigns. Consequently, princeling led funds have adopted a “low profile, high impact” operational style. They avoid the flamboyant public listings of the past decade, preferring strategic minority stakes in “Little Giant” firms—specialized startups that dominate niche markets in aerospace, robotics, and new materials.

Data from 2024 indicates that dollar denominated fundraising by China focused funds dropped significantly, yet RMB funds, often backed by state guidance capital and managed by politically connected firms, remained robust. This “localization” of capital ensures that the profits from China’s technological ascent remain within a controlled ecosystem.

By 2026, the Princelings’ portfolio looks fundamentally different than it did in 2019. It is less exposed to consumer internet platforms and residential real estate, and heavily weighted towards industrial technology and strategic infrastructure. This alignment ensures that as the Party pursues its 2035 vision for a modern socialist nation, the children of its founders remain the primary beneficiaries of the wealth created in the process.

Real Estate Empires: Land Use Rights, Zoning, and Development Monopolies

The narrative of Chinese real estate from 2020 to 2026 is often told as a story of universal collapse. Western headlines focus on the default of private giants and the anger of unpaid suppliers. Yet a closer examination reveals a more complex reality: a sector wide consolidation that has shifted assets from vulnerable private players into the hands of State Owned Enterprises (SOEs) with deep political lineage. For the Princelings, the children of the Red Aristocracy, the crisis was not an end but a reshuffling. The era of the cowboy developer is over; the era of the State Landlord has returned.

The Red Shift: From Private Wealth to State Power

Prior to 2020, Princelings often operated through private equity vehicles or opaque offshore trusts, partnering with aggressive private developers to secure land deals. The mechanism was simple: the developer provided the capital, and the Princeling provided the guanxi needed to unlock zoning changes and land use rights. However, the Three Red Lines policy of 2020 and the subsequent credit crunch shattered this model. Private capital dried up, leaving only those with direct access to state banks standing.

By 2024, the market share of state owned developers had surged. Data from 2025 indicates that while private sector defaults exceeded 50 billion USD annually, state backed entities like Poly Developments and China Resources Land solidified their dominance. These firms are not merely government arms; they are the traditional fiefdoms of the Party elite. The crisis effectively renationalized the most valuable commodity in China: urban land.

The Mechanism: Two Stage Auctions and Zoning Control

The primary lever of control remains the land auction system. On paper, all land is sold via public auction. In practice, a “two stage auction” system allows local officials to steer prime plots to favored entities. Academic analysis of land sales between 2023 and 2025 confirms that connected firms consistently acquire land at discounts relative to market value, often because the auction conditions are tailored to exclude competitors.

Zoning power is equally critical. A plot designated for industrial use is worth a fraction of one zoned for luxury residential. The power to alter these designations lies with local planning bureaus, often staffed by allies of regional Party bosses. Throughout 2024, as the property market cooled, the few profitable developments were those in Tier 1 cities like Shanghai and Beijing where zoning exceptions were granted to SOEs, allowing them to build higher density luxury units than normally permitted.

“The era of the cowboy developer is over; the era of the State Landlord has returned. The crisis effectively renationalized the most valuable commodity in China: urban land.”

Case Study: The Vulnerable Niece and Fantasia Holdings

The limits of this power were tested in the saga of Fantasia Holdings. Founded by Zeng Baby, the niece of former Vice President Zeng Qinghong, Fantasia was once the poster child for Princeling real estate power. It specialized in luxury residences and lifestyle services, banking on the prestige of its founder.

However, political winds shift. As the factional balance in Beijing changed, Fantasia found itself without the infinite credit lifeline extended to others. By May 2024, the company was forced into a complex debt restructuring. Zeng Baby retained a 40 percent stake, but the restructuring forced a conversion of 1.3 billion USD in debt to equity, diluting control and wiping out significant value. The Fantasia case serves as a warning: in the new era, individual lineage is secondary to direct state control. A Princeling operating outside the safety of a central SOE is now vulnerable.

Case Study: The Iron Throne of Poly Group

In stark contrast stands Poly Developments and Holdings, a subsidiary of China Poly Group. Originally founded by the People’s Liberation Army and historically led by relatives of Deng Xiaoping and Wang Zhen, Poly represents the fusion of military, state, and party power.

2024 Market Data Snapshot

While private competitors saw revenue collapse by 50 percent or more, Poly Developments reported 2024 revenue of approximately 311 billion RMB. Though this represented a slight decline of 10 percent from previous highs, it secured the firm’s position as the market leader. More importantly, in late 2024, Poly accounted for nearly 70 percent of land acquisitions in Tier 1 cities among top developers.

Poly did not suffer from the credit drought. State banks continued to issue bonds on its behalf, allowing it to acquire land cheaply from distressed private firms. In November 2024 alone, Poly acquired six major land parcels in Shanghai and Xi’an. The firm effectively acted as a predator, consuming the assets of failed private developers at a discount. For the families behind the Poly structure, the crisis was an opportunity to consolidate a monopoly over the future development of China’s megacities.

Conclusion: A Portfolio Consolidated

The years 2020 to 2026 transformed the Princeling real estate portfolio. It is no longer about quick flips and private jets financed by offshore dollar bonds. It is about systemic control. The children of the Party elders now sit atop massive state conglomerates that own the land, the zoning rights, and the financing channels. They have traded volatility for permanence, ensuring that as China urbanizes, the rent will always be paid to the state, and by extension, to them.

The Military Industrial Complex: Poly Group and the Arms Trade Legacy

The intersection of dynastic privilege and global warfare finds its starkest expression in the China Poly Group Corporation. Founded by the “Red Nobility”—most notably Wang Jun, son of Vice President Wang Zhen, and He Ping, son in law of Deng Xiaoping—Poly Group was never a mere company. It was the princelings’ personal brokerage for military might. While the founders have passed or retired, the structure they built remains the apex predator of the Chinese defense sector. In the era from 2020 to 2026, Poly Group has evolved from a simple arms dealer into a diversified conglomerate where luxury real estate profits cross subsidize the export of advanced weaponry to sanctioned regimes.

The true nature of this entity was laid bare on June 12, 2024, when the US Department of the Treasury designated Poly Technologies, the group’s primary defense subsidiary, for its role in fueling the war in Ukraine. Despite Beijing’s official claims of neutrality, investigative data revealed that Poly Technologies facilitated the transfer of sensitive dual use technology to Russian defense firms. Specifically, the company shipped radar antenna parts critical for the S 400 surface to air missile system and components for military helicopters. These transactions were not rogue operations but calculated maneuvers by a state owned enterprise deeply embedded in the Communist Party elite network.

The resilience of Poly Group lies in its massive civilian shield. Unlike traditional defense contractors that rely solely on government procurement, Poly operates a vast real estate empire that funds its geopolitical adventures. Financial reports from 2023 show that Poly Developments and Holdings, the group’s property arm, generated revenue of 347.15 billion yuan (approximately $48 billion). This figure was the highest among all listed real estate companies in China, defying a broader sector collapse. This commercial success allows the group to absorb sanctions and maintain liquidity for its capital intensive defense projects. It is the ultimate realization of “military civil fusion,” where apartment sales in Shanghai effectively underwrite missile technology transfers to Moscow.

The legacy of the princelings ensures that Poly operates with a degree of immunity unavailable to private firms. While President Xi Jinping launched aggressive purges against corruption in the rocket force and equipment development departments in 2024—leading to a reported 10% revenue drop for top Chinese arms firms according to SIPRI data—Poly Group largely retained its strategic footing. Its influence extends far beyond borders. In South Asia, Poly Technologies secured a landmark deal to construct the Pekua submarine base in Bangladesh. Valued at $1.2 billion and inaugurated in 2023, this facility fundamentally alters the naval balance of power in the Bay of Bengal, granting the Chinese Navy a critical logistical node under the guise of commercial cooperation.

Between January 2022 and early 2026, Poly Technologies faced repeated US sanctions for missile proliferation activities. Yet, the flow of advanced weaponry continues. The company has adapted by using complex shell structures and transshipment points to evade export controls. For the princelings who still hold sway in the shadows of the Forbidden City, Poly Group remains their most potent portfolio asset. It is a vehicle that converts their historical political capital into hard currency and hard power. As the world watches the visible movements of the People’s Liberation Army, it is the invisible ledger of Poly Group—balancing luxury condos against cruise missiles—that truly funds the expansion of Chinese hegemony.

Rare Earths and Mining: Controlling Strategic Resources and Global Supply Chains

The consolidation of the Chinese mining sector between 2020 and 2026 represents more than a strategic industrial policy. It marks the final enclosure of the periodic table by the Red Aristocracy. While the world focused on the geopolitical implications of the China Rare Earth Group (CREG) formation in December 2021, a quieter transformation occurred within the shareholder registers and opaque holding companies that circle these state owned giants. The children of the Party elders, the princelings, have shifted their portfolio from vulnerable real estate assets to the bedrock of the global technology stack: critical minerals.

The Monolith: China Rare Earth Group

The establishment of CREG in late 2021 was the pivotal moment. By merging the rare earth units of China Minmetals, Chinalco, and the Ganzhou Rare Earth Group, Beijing created a super entity controlling nearly 70 percent of the nation’s heavy rare earth production. While Ao Hong served as the public face and Chairman, the structure of the entity placed it directly under the supervision of SASAC (State owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission). This centralization allowed the elite families to streamline their extraction of rents. Instead of navigating competing fiefdoms in Jiangxi or Inner Mongolia, influence could now be exerted through a single pressure point in Beijing.

The Private Equity Nexus

The mechanism of control is rarely direct operational management. Instead, it operates through private equity vehicles that profit from the state backed monopoly. Boyu Capital, founded by Alvin Jiang (grandson of former leader Jiang Zemin), exemplifies this model. While Boyu is often associated with technology and consumer sectors, the firm’s ability to navigate state restricted industries remains its golden ticket. As the mining sector consolidated, private equity flows into “mining technology” and “resource processing” subsidiaries spiked. These ancillary companies, often holding exclusive contracts with CREG for processing or logistics, serve as the collection vessels for the elite.

Historical precedents guide this modern strategy. The family of former Premier Wen Jiabao, specifically his wife Zhang Beili, once dominated the diamond and gemstone trade through state linked entities. That blueprint has been industrialized. Today, the extraction is not just of gems but of dysprosium and terbium, elements essential for every electric vehicle and guided missile in Western arsenals.

Weaponization of Supply Chains (2023 to 2026)

The princelings have overseen a shift from commercial exploitation to strategic weaponization. On December 21, 2023, China banned the export of rare earth extraction and separation technologies. This move effectively locked Western mining startups out of the processing game, ensuring that even if raw ore was mined in Australia or the US, it had to return to China for refining.

The leverage increased in October 2025, when the Ministry of Commerce introduced strict export restrictions on seven additional rare earth elements. Data from late 2025 showed that global prices for permanent magnets spiked by 40 percent in the weeks following the announcement. This volatility enriched the insiders who held stockpiles and futures contracts, trading on information regarding the timing of state bans.

The 2026 Purge and Absolute Control

The landscape shifted violently in January 2026 with the investigation into General Zhang Youxia. As a prominent princeling and Vice Chairman of the Central Military Commission, Zhang represented the old guard of military industrial power. His removal signaled that Xi Jinping was tightening the circle. The privileges of the princelings in the mining sector are now conditional on absolute loyalty to the Core. The “Princelings’ Portfolio” is increasingly becoming a centralized trust managed by the state, where dividends are distributed only to those who toe the line.

By early 2026, the suspension of export controls negotiated in a temporary trade truce was set to expire. The threat of a total blockade remains the ultimate leverage. For the families holding the keys to these resources, the tension between the West and China is not a crisis but a business model. They control the choke points of the 21st century economy, and they are exacting a toll on every microchip and motor produced worldwide.

Infrastructure and Logistics: Railways, Shipping, and the Belt and Road Initiative

The era of fragmented fiefdoms is over. In the years following 2020, the vast machinery of Chinese logistics and infrastructure underwent a quiet but brutal consolidation. The children of the Party elite, once visible board members collecting rents on every kilometer of track and every shipping container, have receded into the shadows of holding companies and private equity funds. Today, the portfolio is centralized, streamlined, and directed by the ultimate “Red Nobility” in Beijing.

By early 2026, the sector reflects a new reality: infrastructure is no longer just a cash cow for connected families but a strategic weapon for the state. The princelings who remain are not merely collecting dividends; they are executing the “New Three” strategy, pivoting from steel and concrete to electric vehicles, batteries, and renewable energy grids along the Belt and Road.

The Iron Arteries: China State Railway Group

The China State Railway Group (CR) stands as a testament to this centralized power. While the Ministry of Railways was once a notorious kingdom of corruption, the modern CR is a disciplined instrument of state policy. By the end of 2024, the national railway network had expanded to a staggering 162,000 kilometers. The high speed rail network alone exceeded 48,000 kilometers, connecting 97 percent of cities with populations over 500,000.

2024 Data: CR operated a network of 162,000 km. High speed rail track length surpassed 48,000 km.

The leadership at CR, including Chairman Liu Zhenfang and General Manager Guo Zhuxue, operates under strict oversight. The days when a single family could treat the rail ministry as a personal bank account are gone. Instead, the elite families now exert influence through the financing arms that fund these massive deficits. The debt burden is immense, yet the political capital generated by connecting the tibetan plateau to the manufacturing hubs of Guangdong is considered a worthy return on investment.

The Maritime Silk Road: COSCO and China Merchants

At sea, the consolidation is even more pronounced. Two giants dominate the waves: COSCO Shipping and China Merchants Group (CMG). These entities are the operational hands of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). In 2025, COSCO launched its “Day Nine” product line, further tightening its grip on global supply chains from Southeast Asia to the Mediterranean.

China Merchants Group, headquartered in Hong Kong, serves as a prime example of how the “Red DNA” has evolved. Chairman Miao Jianmin, a technocrat with deep ties to the state insurance sector, oversees an empire that controls ports from Sri Lanka to Djibouti. The group is not just a shipping company; it is a landlord for the world. By the end of 2024, its subsidiary China Merchants Shekou alone boasted total assets of 860 billion RMB.

2024 Financials: China Merchants Shekou reported assets of 860.3 billion RMB. The group operates across more than 100 cities globally.

The princeling influence here is subtle. It lies in the “mixed ownership” funds and the Hong Kong based investment vehicles that partner with CMG on overseas acquisitions. Families associated with the founding revolutionaries maintain their wealth not through direct management, but through the opaque layers of shareholding structures that sit above these operational giants.

Belt and Road 2.0: The Green Shift

The most significant shift in the 2020 to 2026 period is the transformation of the Belt and Road Initiative. The “concrete diplomacy” of the past decade has given way to “green development.” In the first half of 2025 alone, BRI construction contracts and investments hit a record high of 124 billion USD. This surge was driven not by coal plants, but by the export of China’s dominant green technology.

2025 Surge: BRI projects recorded 124 billion USD in new contracts and investments in the first six months of 2025.

This pivot benefits a new class of politically connected elites who positioned themselves early in the EV and battery supply chains. The “New Three” industries have become the primary export of the BRI, replacing the surplus steel and cement of the previous era. The families who control the critical mineral supply chains and the battery manufacturers are the new power brokers, leveraging the state logistics network to flood global markets with green tech.

The Silent Shareholders

Investigating the share registers of the subsidiaries supplying these massive projects often reveals a labyrinth of shell companies registered in the British Virgin Islands or the Cayman Islands. While the face of the enterprise is a Party loyalist like Miao Jianmin or Liu Zhenfang, the beneficiaries of the construction subcontracts and the financing deals often bear the surnames of the revolutionary elders.

They have learned the lesson of the anti corruption campaigns: visibility is liability. Control is no longer about sitting in the chairman’s seat; it is about owning the flow of capital that feeds the beast. The trains run on time, the ships sail on schedule, and the dividends flow quietly into the offshore accounts of the silent shareholders.

The Offshore Network: Shell Companies, Tax Havens, and the Panama Papers Revelations

The architecture of wealth in China has undergone a seismic shift since the revelations of the Panama Papers, yet the fundamental mechanics remain robust. While the Communist Party promotes “Common Prosperity” to address inequality at home, the princelings—children of the revolutionary elders—have adapted their strategies for offshore asset protection. The period between 2020 and 2026 reveals a sophisticated evolution from simple Caribbean shell companies to complex trusts in Singapore and compliant structures designed to withstand global scrutiny.

The Pandora Papers and the Scale of Hidden Wealth

The release of the Pandora Papers in October 2021 provided a rare window into the financial secrecy of the Red Aristocracy. While the 2016 Panama Papers exposed the initial framework, the 2021 leak was far more damaging in its specificity. The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists identified nearly 2,000 Chinese citizens among the beneficiaries of secret offshore entities. This cohort included relatives of high ranking officials who utilized the British Virgin Islands (BVI) not merely for tax avoidance but to circumvent strict capital controls.

These documents revealed that despite the anticorruption drives of the previous decade, the elite had not repatriated their wealth. Instead, they buried it deeper. The use of nominee shareholders and opaque corporate registries allowed princelings to hold stakes in industries ranging from real estate to green energy without their names ever appearing on a mainland ledger.

The Singapore Exodus: A New Safe Harbor

As geopolitical tensions with the West escalated and the BVI faced pressure to open its books, Chinese capital sought a new sanctuary. Between 2023 and 2025, Singapore emerged as the primary destination for this flight of capital. The city state offered stability, neutrality, and a legal system based on English common law.

Data from the Monetary Authority of Singapore illustrates this trend with clarity. The number of Single Family Offices (SFOs) in Singapore surged from approximately 400 in 2020 to over 1,400 in 2023. By the end of 2024, that figure had climbed to 2,000, representing a 43% increase in just twelve months. Wealth managers estimated that roughly half of these new setups were linked to mainland Chinese wealth seeking protection from domestic regulatory storms.

“The shift to Singapore is not just about tax,” notes a Hong Kong based financial analyst. “It is about the preservation of dynasty. The princelings are moving assets into structures that can survive the political currents of Beijing.”

The August 2025 Tax Enforcement Campaign

Beijing did not remain idle as billions flowed southward. In August 2025, the State Taxation Administration launched a targeted campaign to enforce tax collection on overseas income. This initiative marked a turning point in the relationship between the Party and its wealthiest scions. Authorities began enforcing a long dormant rule requiring residents who spend more than 183 days a year in China to pay a 20% tax on their global investment profits.

Reports from Shanghai and Zhejiang in late 2025 indicated that wealthy individuals were receiving summonses to audit their offshore holdings. This domestic squeeze created a paradox: the princelings needed to move money out to ensure safety, yet the act of moving it became increasingly perilous. The response was a pivot toward “compliant offshoring,” where assets were declared but held in irrevocable trusts that technically separated legal ownership from the beneficiary, muddying the waters for tax collectors.

The VIE Loophole and Wall Street

The primary vehicle for this wealth transfer remains the Variable Interest Entity (VIE). This legal structure allows Chinese companies to list on foreign exchanges like the NYSE or NASDAQ through a shell company in the Cayman Islands. Despite threats from both American regulators (via the Holding Foreign Companies Accountable Act) and Chinese cybersecurity watchdogs, the VIE structure survived the regulatory blizzards of 2021 and 2022.

By 2026, the VIE had evolved. It was no longer just a tool for tech giants like Alibaba or Tencent. Smaller firms controlled by princeling networks utilized VIEs to list niche companies in sectors like biotechnology and electric vehicles. These listings provided a legitimate channel to convert RMB denominated assets into USD equity, liquidating wealth into the global financial system before the domestic doors could close completely.

The offshore network is no longer a static collection of secret bank accounts. It is a dynamic, living organism that reacts to policy changes in Beijing and Washington. For the princelings, the game has shifted from simple concealment to complex legal navigation, ensuring that their portfolios remain beyond the reach of the very state their families helped build.

Regulatory Capture: How Policy is Crafted to Protect Family Monopolies

The narrative of the Chinese market from 2020 to 2026 is often told as a story of strict governance curbing disorderly capital. However, a closer examination reveals a different reality. The regulatory blizzard that chilled the private tech sector was not merely a public safety measure. It was a hostile takeover by the state apparatus, designed to secure the portfolios of the Red Nobility. By 2025, the mechanism of control had shifted from simple ownership to regulatory capture, ensuring that key industries remain the exclusive domain of Party elders and their progeny.

The Golden Share Stratagem

The most blatant tool in this arsenal is the “Special Management Share,” colloquially known as the Golden Share. Initiated aggressively in 2023, this policy allows state backed entities to acquire a mere 1% stake in private companies while obtaining absolute veto power and board representation. This is not passive investment; it is active command.

In January 2023, the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC), through a subsidiary, took a 1% stake in Guangzhou Lujiao Information Technology, a core unit of Alibaba. This move bypassed the need for a costly buyout while granting the Party state decisive control over content and strategy. Similar stakes were taken in units of Tencent and ByteDance. For the princelings who operate within the opaque nexus of state funds and private equity, this mechanism creates a moat. It prevents grassroots disruptors from challenging the incumbents that generate wealth for the elite.

The Fintech Reallocation

The suspension of the Ant Group IPO in late 2020 was the opening salvo. While publicly framed as financial risk mitigation, the subsequent restructuring served the interests of the state banking monopoly. By 2024, Ant had been forced into a financial holding company structure, subjecting it to the same capital requirements as state banks but without their safety net. This neutralized the threat Ant posed to the traditional lenders, sectors long dominated by families such as the Chens and the Wangs.

Investigative records reveal that early investors in Ant included Boyu Capital, a private equity firm founded by Alvin Jiang, the grandson of former leader Jiang Zemin. Through a complex web of shell companies like Beijing Jingguan Investment Center, Boyu held significant equity. The regulatory crackdown did not destroy this value; it preserved the status quo. By clipping the wings of Jack Ma, the Party ensured that no private individual could outshine the collective authority of the families.

Resource Consolidation

In the strategic resources sector, regulatory capture manifests as forced consolidation. The formation of the China Rare Earth Group in December 2021 provides a stark example. The state merged rare earth assets from three massive SOEs—Aluminum Corporation of China, China Minmetals, and Ganzhou Rare Earth Group—into a single behemoth. This entity now controls nearly 70% of the nation’s heavy rare earth production.

This merger eliminated domestic competition and centralized pricing power under the State owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC). For the elite families who control the supply chains and logistics contracts surrounding these mining giants, the monopoly guarantees stable rents extracted from global demand. The 2024 updates to the Mineral Resources Law further tightened this grip, making it nearly impossible for private or foreign entities to operate in the sector without partnering with this new leviathan.

The Illusion of Fair Competition

The 2024 revision of the Anti Monopoly Law introduced the “Three Letters and One Notice” system, ostensibly to guide companies toward compliance. In practice, this system grants regulators discretionary power to target specific firms while sparing others. Data from 2025 indicates that while private ecommerce platforms faced continued scrutiny, state cloud providers like China Telecom received regulatory tailwinds, allowing them to capture market share from Alibaba Cloud and Tencent Cloud.

The pattern is unmistakable. Regulations are crafted not to level the playing field but to tilt it permanently in favor of the Princelings’ Portfolio. Whether through the 1% Golden Share or the creation of massive state monopolies, the policy landscape of 2026 is designed to protect the wealth of the few at the expense of the many.

The Insurance Giants: Anbang, Tomorrow Group, and the Gray Rhinos

The era of the Gray Rhino has ended, not with a whimper, but with the definitive thud of the gavel and the quiet scratching of pens on liquidation orders. Between 2020 and 2026, the Chinese state systematically dismantled the private financial empires that once served as the unofficial treasuries for the Red Nobility. The insurance sector, once a playground where the children of Party elders and their proxies leveraged cheap premiums into global trophy assets, has been forcibly restructured. The portfolio is no longer in the hands of rogue tycoons; it has been reclaimed by the state itself.

The End of the Anbang Illusion

The saga of Anbang Insurance Group, built by Wu Xiaohui, offers the clearest case study of this reclamation. Wu, who married into the family of former Premier Zhu Rongji, once used Anbang to acquire the Waldorf Astoria in New York. By 2020, Wu was in prison, and the state had stepped in. The cleanup vehicle, Dajia Insurance Group, spent the first half of the decade struggling to unwind the mess.

In 2024, the National Financial Regulatory Administration finally approved the bankruptcy proceedings for the original Anbang entity, formally burying the corporate shell. Dajia spent the subsequent year aggressively shedding the remaining international assets. By July 2025, Dajia completed the sale of its South Korean units, Tongyang Life and ABL Life, alongside Belgium based Nagelmackers Bank. The global footprint Wu built to move capital abroad was erased, sold off to repatriate funds to cover domestic debts.

The Waldorf Astoria stands as the final, ironic monument to this era. After years of delays and cost overruns exceeding two billion dollars, the hotel finally reopened in early 2025. It remains under the ownership of Dajia, meaning the Chinese state effectively became the landlord of this American icon. The property that was once a symbol of princeling ambition is now a distressed asset on a government balance sheet, managed by Hilton but owned by the People.

Tomorrow Group and the Great Consolidation

If Anbang was about trophy assets, the Tomorrow Group was about systemic capture. Xiao Jianhua, the Canadian Chinese tycoon who served as a white glove for multiple elite families, was sentenced to 13 years in prison in August 2022. His conglomerate was fined 55 billion yuan, but the real story was the disposal of his insurer assets, which had acted as shadow banks for the politically connected.

The dismantling process peaked in 2023. Huaxia Life, the crown jewel of the Tomorrow empire with billions in revenue, did not go to a private buyer. Instead, the state created a new entity, Ruizhong Life, to absorb it. Ruizhong is controlled by the China Insurance Security Fund and a fund backed by China Life. This transfer effectively nationalized the cash flow that Xiao once directed. The private wealth management vehicle was converted into a state utility.

Similar fates befell other arms of the empire. Tianan Life was rolled into the new Zhonghui Life in 2023. In a rare instance of tech sector involvement, the electric vehicle giant BYD acquired the bankrupt Yi’an Property Insurance in May 2023, rebranding it as BYD Insurance. This move signaled a shift in preference: the state preferred industrial champions taking over these assets rather than letting other financial speculators step in.

The New Portfolio Managers

By 2026, the landscape had shifted entirely. The National Financial Regulatory Administration, established in 2023 to tighten oversight, now enforces a regime where insurance funds are directed toward national strategic priorities like infrastructure and technology, rather than overseas acquisitions or real estate speculation. The families that once used Anbang and Tomorrow Group as personal piggy banks have either exited the game or realigned their interests with these new state backed giants.

The gray rhinos were the obvious threats that everyone ignored: high leverage, opaque ownership, and political patronage. The crackdown from 2020 to 2026 did not just remove the threat; it seized the capital. The Princelings’ Portfolio is no longer hidden in offshore trusts managed by proxies like Xiao or Wu. It is now embedded within the opaque but stable balance sheets of sovereign funds and state insurers, safe from the volatility of the market but firmly under the thumb of the Party Core.

Luxury, Art, and Media: Soft Power and the Monetization of Cultural Influence

The transformation of elite capital in China has shifted. While the early 2000s saw the Red Nobility capture hard industries like energy and telecommunications, the 2020s have defined a new era: the monetization of soft power. The children and grandchildren of Party revolutionaries now dominate the ephemeral worlds of high art, luxury fashion, and blockbuster cinema. This sector allows for opaque valuations and rapid wealth transfer, all while curating a patriotic narrative that aligns with Beijing.

The Auction House Gatekeepers

Nowhere is this influence more visible than in the art market. Two giants dominate this landscape: Poly Auction and China Guardian. Both have deep roots in the revolutionary lineage.

Poly Culture, a division of the state run China Poly Group, was originally forged by Wang Jun, the son of Vice President Wang Zhen. In 2025, Poly Auction continues to command the Asian market. The firm acts as a primary channel for repatriating cultural relics, a political priority that conveniently drives massive turnover. The blurred lines between state mission and private profit are stark. When a Ming Dynasty vase sells for record sums, the commissions fuel a corporate engine built on military origins.

Competing alongside is China Guardian, founded by Wang Yannan, the daughter of former Premier Zhao Ziyang. In the spring of 2025, Guardian Hong Kong displayed its power during the April sales. A single lot, a pair of celadon double gourd vases from the Qianlong period, fetched over 46 million Hong Kong dollars. These transactions are not merely commercial. They represent the transfer of wealth into portable, tangible assets, often overseen by firms with untouchable political pedigrees. The auction block has become the preferred clearinghouse for elite capital.

The Red Designers: Wearable Influence

Beyond the auction gavel, the princelings have curated a distinct niche in personal luxury. Wan Baobao, granddaughter of former Vice Premier Wan Li, exemplifies this trend. She has successfully transitioned from a socialite in the Forbidden City to a jewelry mogul. Her brand, Bao Bao Wan Fine Jewellery, targets the ultra wealthy who seek valid cultural signifiers.

In 2023 and 2024, Wan expanded her presence in Hong Kong luxury retailers like Lane Crawford. Her collections, such as “And the Little Ones,” feature pendants shaped like pagodas and pandas. These are not cheap trinkets. Prices for her premium line soar above six figures. By leveraging her upbringing in Zhongnanhai, Wan sells more than diamonds; she sells access to an exclusive revolutionary aesthetic. She effectively monetizes her lineage, turning political heritage into a consumer brand that appeals to the new money of the Greater Bay Area.

Cinematic Capital and Narrative Control

The third pillar of this portfolio is the film industry. The years 2024 through 2026 have seen a surge in patriotic blockbusters, a genre where political correctness meets commercial viability. Princeling capital often flows into the private equity funds that finance these productions.

The 2025 release of Ne Zha 2, which grossed 4.8 billion yuan, and the 2026 release of Pegasus 3 highlight this synergy. While the studios may appear public, the financing structures often trace back to funds connected to the Red Nobility. These investors understand that safe, nationalist content guarantees regulatory approval and box office protection. By backing films that align with the core values of the Party, they ensure their investments remain secure from the regulatory storms that have battered other sectors like tech or education.

In this portfolio of soft power, the Party elders children have found the perfect hedge. Art, jewelry, and film offer prestige, portability, and profit, all insulated by the ultimate shield: their family names.

The Ivy League Pipeline: Western Education as a Networking and Credibility Tool

For the children of the Red Nobility, a degree from Harvard, Stanford, or Columbia is rarely about the coursework. It is a strategic asset class. Between 2020 and 2026, as geopolitical frost settled over Sino American relations, the function of this education shifted. It evolved from a simple prestige marker into a critical mechanism for wealth preservation and capital extraction. The “Ivy League Pipeline” now serves as the primary credibility wash for the princelings, allowing the scions of Party elders to rebrand inherited political power as meritocratic financial acumen.

The mechanics of this pipeline are visible in the private equity sector. While the broader Chinese venture market faced a contraction from 2023 to 2024, firms with deep political lineage continued to attract Western limited partners. The resume of a typical princeling financier follows a rigid pattern: an undergraduate degree from a top American university, a brief stint at a Wall Street bank like Goldman Sachs or Morgan Stanley, and a return to China to helm a private equity fund. This trajectory effectively launders their reputation. To a Western pension fund or endowment, investing in a firm led by a “Stanford graduate with Goldman experience” feels safer than handing money directly to the son of a Politburo member. The degree acts as a compliance shield.

Recent data highlights the financial divergence driven by these credentials. In 2024, while yuan denominated fundraising in China plummeted by nearly 20 percent due to economic headwinds, the top tier of dollar denominated funds remained resilient. These funds are disproportionately controlled by the political elite. For instance, Boyu Capital, cofounded by Alvin Jiang (grandson of former leader Jiang Zemin), exemplifies how Western credentials and political access blend to capture billions in capital. The firm does not merely trade on guanxi; it trades on the comfort that Western institutional investors feel when dealing with Western educated managers who speak their language.

However, the pipeline faced unprecedented pressure between 2024 and 2026. Legislative maneuvers in Washington, such as the introduction of the “Stop CCP VISAs Act” in 2025, sought to sever these academic ties. Proponents like Senator Eric Schmitt argued that American universities should not educate the children of an adversary. Yet, investigative analysis suggests these bans primarily impact the rank and file or those in sensitive STEM fields. The core princelings, often enrolled in law, business, or the humanities, have largely evaded such nets. If anything, the tightening of visa restrictions has artificially inflated the value of existing degrees. A Harvard MBA held by a princeling in 2026 is now a scarcer, and thus more valuable, commodity than it was a decade prior.

The utility of the network extends beyond fundraising. It functions as an insurance policy. As domestic purges under the anti corruption drive continued through 2025, possession of an overseas network provided a potential exit ramp. The alumni networks of Yale or Princeton offer a soft landing in New York or London should political tides in Beijing turn fatal. This “hedge” explains why, despite the nationalist rhetoric promoted domestically by the CCP, the elite continue to send their progeny West.

By 2026, the data indicates a consolidation of this trend. The “sea turtles” (haigui) who return are no longer just seeking employment; they are returning to act as gatekeepers. They control the chokepoints where Western capital seeks entry into Chinese markets. In this ecosystem, the diploma is not a certificate of learning. It is a membership card to a transnational oligarchy that operates above the fray of national rivalries, ensuring that regardless of the diplomatic weather, the portfolio remains secure.

Xi’s War on Graft: Purging Rivals vs. Consolidating Red Capital

By February 2026, the narrative surrounding the campaign against corruption in China had shifted irrevocably. Once viewed by external observers as a mechanism to clean the bureaucracy, the relentless drive has morphed into a surgical tool for centralizing financial power. The years between 2020 and 2026 revealed a distinct pattern: the systematic dismantling of “white glove” financiers who managed assets for rival factions, followed by the absorption of their empires into state enterprises controlled by loyalists. This was not merely about punishment; it was about the transfer of the ledger.

The Fall of the Proxies

The era of the untouchable private broker ended decisively with the sentencing of Xiao Jianhua in August 2022. Xiao, the founder of Tomorrow Group, had long served as a financial proxy for the families of the political elite. His abduction from Hong Kong and subsequent thirteen year prison term signaled that the old pacts were void. The court fined his conglomerate 55 billion yuan, effectively nationalizing its vast holdings in banking and insurance. This move stripped rival lineages of their primary funding vehicles, leaving them politically exposed and financially neutered.