Top Media Communication Case Studies For Powerful Media Relations Services

Why it matters:

- PR agencies utilize media communication to shape brand reputation, manage crises, and influence policy across various sectors and countries.

- Effective PR strategies involve proactive media relations, crisis communication, and narrative-shaping techniques to protect and promote clients.

Media Communication – the strategic use of news outlets, press events, and social platforms – is central to public relations (PR) and media relations. PR firms deploy media communication tactics to shape brand reputation, manage crises, and influence policy.

This investigation examines how PR agencies craft narratives and engage with media across sectors and countries. It analyzes concrete examples from technology, healthcare, and government, and compares practices globally (with emphasis on the United States). We document how media messaging affects public opinion, policy formation, crisis outcomes, and brand perception, citing facts and expert observations throughout.

PR Strategies for Reputation, Crises, and Influence

PR agencies use proactive media relations and crisis communication to protect and promote clients. Effective reputation management leverages media trust: for instance, one report notes that “95% of customers trust corporations that are well-regarded”.

PR specialists therefore work preemptively, cultivating positive press and stakeholder goodwill. Tactics include crafting favorable press releases, arranging interviews, and responding rapidly to criticism. As Prowly (a PR platform) explains, traditional PR focuses on “press releases and building relationships with journalists” to manage image and visibility.

In crisis situations, PR shifts into damage control. The goal is often to “narrative-shape” events before misinformation spreads. One veteran PR consultant advises never hiding bad news: “Don’t be afraid to lead with bad news, but always follow it with a solution”【24†】. (For example, HubSpot quotes Dana White of 5WPR: “Don’t be afraid to lead with bad news, but always follow it with a solution.”) PR teams may also set up hotlines, hold press conferences, and deliver unified messaging.

The 1982 Tylenol poisoning case is a classic example: Johnson & Johnson’s CEO James Burke famously asked “How do we protect the people?” and immediately halted production, withdrawing Tylenol nationwide and issuing media alerts. By using open media communications and new safety seals, J&J turned public fear into trust, with news outlets reporting that the company was acting in the public interest.

Beyond reputation and crisis, PR can shape policy and government relations. Modern PR firms often advise corporate and political clients on how to influence legislation and public sentiment via media. As an academic review notes, “media, old and new, are the main arena for the battle over the scope of policy conflict”.

In practice, this means firms may coach politicians on talking points, arrange favorable media coverage for policy initiatives, or run public campaigns on regulatory issues. For example, The Guardian revealed that global PR leader Edelman was paid by authoritarian regimes like Saudi Arabia and the UAE to promote their image – using its own “Trust Barometer” research to boost these governments’ legitimacy.

Such cases show PR straddles business and government: agencies extert influence by highlighting positive narratives about clients’ actions (often without disclosing vested interests).

PR strategies vary by industry and region. The following sections explore three key sectors – technology, healthcare, and government – highlighting how media communication is used in each. We also compare practices across countries, especially contrasting U.S. norms with those abroad.

Technology Sector Communication

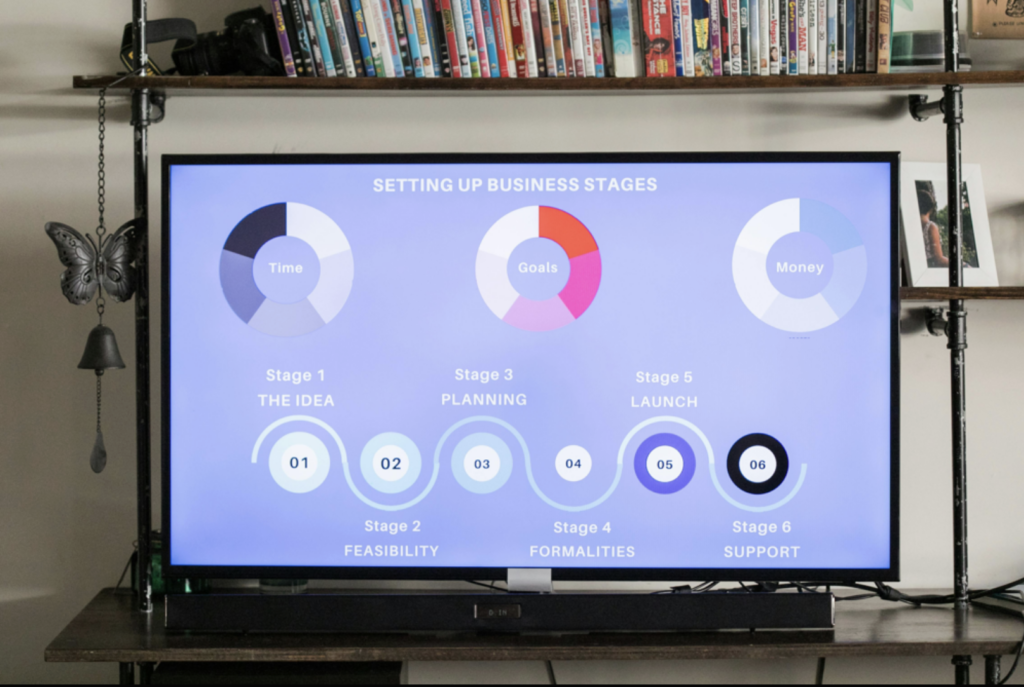

In the fast-paced tech industry, media relations are used to launch products, manage reputation, and respond to controversy. Tech firms often employ skilled PR teams to coordinate messaging around new devices or services. For instance, smartphone and gadget launches are accompanied by press events and influencer campaigns to generate hype. Data also plays a role: companies package user statistics and market research into infographics and press materials (see Figure: Setting up business stages infographic below).

Figure: A technology presentation highlights “Social Media,” “Artificial Intelligence,” and “Big Data.” Tech companies often use such presentations and infographics in media events to explain innovations and shape narratives.

Crisis management in tech: When scandals hit, communication missteps can worsen the crisis. Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) in 2023 offered a cautionary tale. PR experts observed that SVB’s emergency announcements were poorly handled. A blog post described SVB’s main communications piece as a “convoluted press release” that was “received so badly it was almost comical”.

On a subsequent all-hands call, SVB CEO Greg Becker urged employees to “stay calm” and warned “the last thing we need you to do is panic” – precisely the opposite advice a collapsing bank should offer, according to media commentators. These miscommunicated messages accelerated fear, contributing to what was called a “social media bank run”. The SVB case underscores that in technology finance (and beyond), even technically sound decisions can be undermined by faulty media communication.

Influence campaigns: Tech companies also engage with policy through media. For example, during debates over online privacy and antitrust, Silicon Valley firms lobby and issue public statements to sway regulators. Media analysts note how social media platforms have used targeted communications to defend their policies when facing legislation.

During privacy hearings, for instance, a CEO might appear in an op-ed or press interview to assure the public and Congress that new regulations are overblown. These communications aim to influence policy formation by shaping public and political opinion. As one review found, “media coverage and influence on policy making” are tightly linked, meaning tech PR strategies often blur into political advocacy.

Brand-building campaigns: On the positive side, tech giants invest heavily in media to shape brand perception. Example campaigns include IBM’s long-standing image of social responsibility, or Google’s sponsored reports on innovation. These often take the form of multimedia press kits, whitepapers, or third-party media partnerships.

A notable method is creating narrative-driven content (e.g. videos or podcasts) that humanize the technology. Data-backed infographics (like Fig. 1, above) are used to make complex tech concepts accessible, aiming to engage journalists and public alike. Studies even show journalists are significantly more likely to pick up stories when data visualizations are provided (e.g., one PR guide notes journalists are 30% more likely to respond to stories containing clear visuals).

In summary, media relations in tech revolve around product launches and crisis control. PR firms help tech companies present themselves as innovative while mitigating backlash. High-profile cases (from Uber’s public apology to Apple’s product recalls) illustrate the stakes. Tech leaders often become de facto media spokespeople – exemplified when Uber’s new CEO Dara Khosrowshahi addressed regulators after London revoked Uber’s license.

In a now-cited press statement, Khosrowshahi explicitly apologized for past failures: “On behalf of everyone at Uber globally, I apologize for the mistakes we’ve made”. Analysts praised this clear admission as a “masterclass in crisis management” by juxtaposing innovation claims with accountability. His tone was a sharp pivot from Uber’s earlier combative image, highlighting how tellingly direct media communication can reshape tech brand perception.

Healthcare and Public Health Communication

The healthcare sector relies on media to disseminate information about products, research, and public health guidance. PR campaigns by pharmaceutical companies, hospitals, and health agencies aim to build trust in treatments and manage health crises. Media relations here can affect millions, from patients to policymakers.

Pandemic communication: COVID-19 underscored the power of media messaging. Governments and health authorities held daily press briefings; pharmaceutical firms published trial data; social media influencers spread vaccine news. According to media scholars, during the pandemic media coverage often went into “rally-around-the-flag” mode, boosting trust in officials.

Initially, opinion pieces mostly aligned with government messaging to maintain unity. However, expert reviews note that by the second phase media scrutiny grew, reflecting public fatigue. PR teams in health had to adapt: vaccine developers like Pfizer and Moderna used technical press releases and news conferences to reassure the public about safety. Meanwhile, health agencies and NGOs ran extensive media campaigns on mask-wearing and vaccine uptake. The communication goal was clear – align media narratives with public health priorities.

Figure: A reporter wearing a medical mask is interviewed by TV media during the COVID-19 pandemic. In health crises, visual images like this underscore official messaging about safety measures.

Vaccine and medical product campaigns: Beyond crises, healthcare PR boosts product images. Pharma companies often engage third-party experts in media relations. For instance, when Merck’s painkiller Vioxx faced safety questions in 2000, the company enlisted medical researchers for conferences and press outreach (later revealed internal docs showed Merck’s aggressive physician targeting).

Such campaigns are designed to frame products as medically necessary. Similarly, pharma PR teams sponsor continuing medical education events and pitch stories to health reporters.

Public health advocacy: NGOs and advocacy groups also use media relations to influence policy. For instance, anti-smoking campaigns have leveraged press releases and targeted news stories to press for stricter laws. During Ebola or Zika outbreaks, WHO and CDC held press conferences to guide policy.

The academic literature on media and health policy notes that news coverage can drastically affect public response – the “issue-attention cycle” linking media framing to policy action. Indeed, studies cited in the Annual Review suggest that “media coverage of public health epidemics” can shape how seriously governments address them.

Healthcare industry reputation: Brand perception is crucial in healthcare. Hospitals and insurers use media to highlight success stories and community work. The competitive health industry employs PR agencies to manage reputations in case of malpractice lawsuits or data breaches. For example, when a hospital is sued, its PR team often issues statements to news outlets emphasizing patient care standards. Personal testimonies also figure in media strategy; human-interest stories in newspapers can counteract negative press.

Across countries, healthcare media strategies differ by culture. In the U.S., with its free press, companies might face aggressive investigative reporting (e.g., the Purdue OxyContin scandal). In contrast, in some countries pharmaceutical publicity is more heavily regulated, shifting PR efforts to trade media and events rather than broad news. Nonetheless, one constant is that healthcare media relations operate at the intersection of science, business, and government – a complex environment requiring factual messaging and ethical care.

Government and Public Affairs Communication

Media communication in the government sector encompasses official press relations, political PR, and public affairs campaigns. This covers how governments use media to inform (or persuade) citizens, as well as how private PR firms engage with policy issues.

Official government media: Most governments maintain communication offices to issue press releases, hold press conferences, and manage official social media. Effective communication is seen as essential for public trust. Scholars observe a “rally-around-the-flag” effect in crises: if media narratives are favorable, citizens back government policies.

For example, research on COVID media framing suggests early support for leader messages (the so-called “permissive consensus”). However, the media can also amplify dissent; once a crisis deepens, outlets may shift to critical coverage, influencing policy debates.

Government use of PR firms: Outsourcing is common. Governments worldwide hire PR agencies to shape their international image. A recent Guardian investigation revealed that the UAE and Saudi governments paid top firms like Edelman millions to polish their global standing.

These PR contracts often coincide with international events: for instance, the UAE’s use of Edelman in the lead-up to hosting COP28 helped portray its climate efforts in a positive light. Government PR campaigns may involve organizing media tours, supplying talking points to officials, and even influencing whether a country is included in global reports.

In the case of the UAE, insider disclosures showed the government asking PR firms to produce surveys of “influencers in Washington, DC,” and praising media coverage that reported increased citizen trust.

Influence and propaganda: In some regimes, the line between PR and propaganda blurs. PR professionals note how authoritarian states may co-opt global PR tools to legitimize power. As one NYU professor said of Edelman’s Trust Barometer, it’s often “quoted everywhere as if … credible research, whereas there is a fairly obvious commercial background”.

The Guardian quoted this remark to highlight potential manipulation: Edelman’s surveys consistently reported that people “strongly trust their government” in nations like the UAE, a message widely amplified by state media (and even official Twitter accounts) as proof of leadership success. Such examples show how media relations can extend to shaping national narratives.

Lobbying and policy campaigns: Beyond public messaging, media relations often support lobbying. PR firms help clients craft op-eds, organize policy forums, and mobilize “astroturf” citizen groups to influence legislation. For example, in debates on healthcare or energy policy, interested industries run media campaigns to sway public opinion, which in turn pressures lawmakers.

A Washington PR executive notes: “We believe our presence in [Middle East] can help drive change by counseling influential organizations… and building new stakeholder relationships,” reflecting the industry view that media outreach can facilitate policy dialogue. Similarly, corporate advocacy might generate media coverage of “research” that aligns with business goals, effectively setting the agenda for regulatory discussion.

Comparative media relations: Practices vary globally. In the United States, the press relations approach is often adversarial and data-driven: journalists critically scrutinize government statements, so PR must be transparent or risk backlash. In the UK, political PR operates alongside influential party communications teams.

In contrast, in countries with state-controlled media (e.g., China), PR as understood in the West is replaced by government propaganda departments – foreign firms must navigate strict rules and often work through state proxies. The Edelman case illustrated another dimension: a US-based firm using Western-style surveys to bolster non-Western regimes. One analysis notes that research in “27 countries” shows US government spending on media is relatively low compared to some democracies, meaning PR influences may be more covert.

In sum, media communication in public affairs serves multiple masters: informing citizens, shaping policy debate, and managing a country’s image. PR agencies operate at the nexus of government and media; they advise politicians on messaging and sometimes generate content that eventually appears in news outlets. Whether through official press offices or covert campaigns, media relations can significantly influence public opinion.

As one academic review concluded, media attention can become “the main arena for the battle over the scope of policy conflict” – a zone where PR strategies seek to control the narrative.

Cross-Industry Themes and Effects on Public Opinion

Across all sectors, media communication strategies aim to influence public opinion and brand perception. Key patterns emerge:

Framing and narrative control: PR teams craft narratives to frame events favorably. This could mean highlighting positive aspects of a policy (e.g. a company’s environmental initiative) or framing crises as manageable (“we’re taking decisive action”).

Media framing studies show that such narratives strongly affect public reactions. For instance, in health crises, how media “frames” the danger can amplify or reduce fear. In political contexts, repeated messaging can create a bandwagon effect: early, positive coverage of a government’s Covid response helped maintain public trust. Later, when narratives shifted to criticism, public sentiment often shifted as well.

Trust and credibility: Trust is a central factor. The Edelman Trust Barometer (ironically both a research product and a PR tool) tracks public trust in institutions globally. In general, the more credible the source, the more effective the media communication.

PR relies on “earned media” – coverage by independent press – because audiences trust earned media far more than paid ads. For example, surveys report that a large majority of people place more faith in earned news coverage than in corporate advertisements.

This drives PR efforts to earn placement in respected outlets and to involve independent experts. Conversely, if PR is viewed as merely “spin,” it can backfire. One media ethics expert warns that journalistic credibility is undermined when everything becomes PR: as George Orwell quipped, “Journalism is printing something that someone does not want printed; everything else is public relations.” Although Orwell’s comment is from 1943, it resonates today as a caution about the boundary between reporting and messaging.

Visual and data tools: Modern media communication often uses infographics and social media to engage audiences. Data visualizations can distill complex information into compelling graphics. PR agencies may supply journalists with charts and slides (like Fig. 2 below) to support stories.

Such visuals can boost coverage: charts illustrating market trends, health data, or survey results make stories more ‘newsworthy.’ (For example, one PR guide notes that journalists are about 30% more likely to feature stories with data visualizations.)

Even internal planning can be communicated visually; see Figure 2, an infographic of business planning stages, which illustrates how visual aids are used in corporate presentations and can double as media material.

Figure: An example infographics chart on “Setting up business stages.” PR professionals often use such visual data presentations in media pitches to explain strategies and findings. Clear, engaging graphics can increase journalist interest and public understanding.

Sector-specific effects on opinion: In technology, media hype or fear can swing market fortunes. Positive coverage of a tech product can attract customers and investors; negative stories (e.g., data breach headlines) can cause backlash.

In healthcare, public trust in treatments often correlates with consistent, credible media messaging by officials and companies. In government, media narratives about policy (for example, on economic performance or national security) can influence election outcomes. Indeed, political scientists note that news coverage often acts as a “shortcut” to gauge public opinion in policymakers’ minds.

Crisis narratives: The initial framing of a crisis story can dominate public discourse. PR professionals try to align the narrative with their client’s interests early on. For example, after a product recall, if the first media reports emphasize the company’s swift action, public outrage may be defused. Conversely, if early coverage casts blame on the company or government, the crisis narrative hardens.

The Tylenol case shows the advantage of prompt, transparent communication: media coverage quickly labeled Tylenol as a “victim of a malicious crime,” not a failing product. The company’s willingness to communicate openly (“We told consumers not to use Tylenol until we knew more”) framed the narrative as one of consumer protection.

Notable Organizations, Firms, and Incidents

Edelman and Global Government PR

Edelman, the world’s largest PR firm, frequently illustrates the intersection of media and power. Its annual Trust Barometer survey is widely cited in media. However, investigative reports show how Edelman’s role can be controversial. The Guardian revealed that Edelman earned millions from autocratic clients while its public survey highlighted surging trust in those regimes.

Insider quotes pointedly note the conflict: Edelman’s trust survey is taken “as some credible, objective research,” yet it serves as a “sales tool” for undisclosed clients. An Emirati official even touted Edelman’s findings on Twitter as proof that “the people’s trust in the government” was high. This example underscores how a PR firm’s data-driven media output can be used for geopolitical influence.

Johnson & Johnson Tylenol (1982)

The Tylenol cyanide poisoning incident remains a benchmark for crisis PR. When seven people died after taking tainted capsules, Johnson & Johnson immediately activated its PR crisis plan. Chairman James Burke prioritized safety: “How do we protect the people?”.

The company recalled all Tylenol nationwide at great cost and used the media to alert consumers (even setting up hotlines for both customers and journalists). Their transparent press conferences and new tamper-proof packaging won public approval.

One analysis concludes that by openly communicating the threat, J&J managed to have the “public view[ing] Tylenol as the unfortunate victim” rather than the culprit. Journalists nationwide covered the story extensively, but the narrative became one of corporate responsibility, preserving Tylenol’s market in the long run. This case is taught as a “masterclass in crisis communications” for its media-led strategy.

Uber London License (2017)

A more recent tech example is Uber’s license suspension in London. In 2017, Uber’s operational missteps (including Greyball use and reporting failures) led Transport for London (TfL) to declare Uber “not fit and proper.” New CEO Dara Khosrowshahi responded with a highly publicized apology letter. He opened: “On behalf of everyone at Uber globally, I apologize for the mistakes we’ve made”i.

Observers noted this as a concise, media-friendly concession. The incident highlighted how tone and choice of words matter in tech PR: by deviating from their earlier unyielding stance, Uber sought to rebuild trust. As industry commentary noted, such an apology – even with two simple words “I apologize” – represented a “stark change” for the company.

The sentence directly addressed public concerns and was widely quoted in press, influencing the narrative around Uber’s ethics.

Silicon Valley Bank Collapse (2023)

SVB’s failure in 2023 is an example where communications arguably accelerated a crisis. The PR around SVB’s sudden recapitalization attempt was quickly labeled a fiasco. Venture capitalist blogs first raised alarm, then SVB’s own press announcement “was received so badly it was almost comical”.

When CEO Greg Becker told clients not to panic, a TechCrunch journalist immediately observed, “the last thing we need … is panic” was exactly what depositors didn’t want to hear.

This misalignment between message and reality illustrates how poor media advice can have tangible effects. Analysts later cited SVB’s PR failures as lessons: one PR expert said SVB’s Zoom briefing – without Q&A and with vague reassurances – did not “inspire confidence,” helping trigger a run on the bank.

Public Health Messaging During COVID-19

The pandemic spurred unprecedented media relations by governments and health bodies. Daily televised briefings (e.g. by the US White House COVID Task Force) became the focal point for public information. At first, media generally echoed official lines (“remain vigilant, follow guidelines”), contributing to solidarity. But later, coverage diversified to include dissenting voices (lockdown critics, alternative treatments).

Researchers document that in early stages there was an effective “media consensus” in support of emergency policies. PR teams had to adjust as the crisis entered later phases; messaging became more segmented, focusing on vaccination science or economic relief. The health sector’s use of data-driven visuals was also notable: charts of infection curves and vaccine effectiveness were routinely shared with media. These visuals aimed to make technical data understandable to the public and thus direct public opinion toward compliance.

Other Industries and Campaigns

- Tech lobbying: Beyond Uber and SVB, other tech controversies (e.g., Facebook data scandals, Boeing safety issues) have featured high-stakes media communication. Boeing’s 737 Max crisis, for example, involved extensive PR and regulatory communication efforts after two crashes; changes included new leadership emphasizing transparency.

- Environmental and Corporate PR: Major energy and chemical companies often hire PR firms to manage public image around environmental issues. Campaigns like BP’s “Beyond Petroleum” rebranding (executed by ad agencies and PR teams) sought to shift brand perception amid environmental criticism. Similarly, lobbying PR campaigns by industries (e.g., tobacco or plastics) have used front groups and media placements to influence public debate on regulations.

- Government public relations: National health agencies like CDC (US) and WHO internationally illustrate media communication strategies. The weekly “reporter’s roundtable” format, clear branding of advisories, and the cultivation of media relationships (giving reporters early access to data) are strategic PR approaches in the public sector. Country contrasts are stark: in the US, an adversarial press means agencies publish comprehensive briefings and transcripts; in some other countries with state-aligned media, communications may be more scripted and less questioned.

Media Communication and Public Impact

Media relations strategies profoundly shape public opinion and policy:

Influencing public opinion: By controlling the timing, framing, and messengers, PR campaigns aim to guide what the public thinks about an issue. Studies show media attention affects policy knowledge and opinions.

For example, when journalists highlight a company’s environmental commitments (even if greenwashing), public perception of that brand’s sustainability improves. Conversely, persistent negative coverage of a pharmaceutical side-effect can amplify vaccine hesitancy. Research cited in media analysis suggests media coverage of epidemics “link[s] framing and issue attention” – essentially, how health news is reported can alter public priorities.

Shaping policy agendas: Policymakers watch media as a barometer of public concern. A coordinated media campaign can bring an issue onto the legislative agenda. For example, a series of investigative reports on airline safety might pressure Congress to hold hearings. PR teams will often plant stories in sympathetic outlets or organize expert opinions to push for (or against) particular laws.

One analysis notes politicians sometimes trust media coverage even more than polls, using it to justify policy moves. In this way, media communication by PR can indirectly effect policy formation.

Constructing crisis narratives: In crises (health, corporate, political), media narratives quickly form. PR’s influence is seen in which aspects are emphasized. If corporate PR sets up a friendly venue for a press release, media cameras and coverage can be more favorable. If instead grassroots media breaks a story early, the narrative may challenge official accounts.

Media monitoring is common: PR agencies track coverage in real time to adapt messaging. The narrative battle often ends up in the press: for example, media characterized Uber’s aggressive culture under its founder, which forced a narrative shift when the new CEO apologized.

Long-term brand perception: Sustained media strategy can redefine how an organization is viewed. An illustration: after J&J’s Tylenol crisis, the narrative turned to emphasize the company’s integrity and consumer safety record, which healed its reputation in the long term. Conversely, companies that mishandle media relations can suffer lasting damage. The Uber example above shows even one misstep (or apology) can shift a tech brand’s identity.

Finally, comparative research shows wide variation in media trust. U.S. audiences, for instance, have become polarized in which outlets they trust. PR strategies thus adapt: some companies tailor messages to conservative media versus liberal media, or even run region-specific campaigns.

This segmentation of media means PR must often create multiple narratives to reach different demographic segments. Globally, countries like China and Russia use state media to control narratives, limiting independent PR influence. By contrast, Western firms often engage third-party influencers and independent channels to widen reach.

Conclusion and Key Insights

Media communication in PR is a complex, high-stakes field that merges journalism, branding, and strategy. Across industries, successful PR agencies use media to build trust, manage crises, and shape agendas. Real-world cases – from Johnson & Johnson’s decisive Tylenol response to Edelman’s controversial work for governments – illustrate the power and pitfalls of media-driven narratives. Expert analyses confirm that media coverage influences both “public policy-making” and corporate outcomes.

For corporate and policy-focused readers, the lessons are clear: media relations must be proactive, transparent, and consistent. Visual tools like infographics (see Figure 2) can strengthen messages. Quotes from PR veterans emphasize honesty and empathy: straightforward apologies or clear safety alerts can rebuild reputations faster than defensive spin.

Critically, the country context matters – practitioners should adapt strategies to different media cultures. Ultimately, media communication is a decisive factor in public opinion and brand strength. As one review notes, the evolving media landscape (old and new) is the battleground for policy and reputation. Mastery of this domain is essential for any organization seeking to navigate crises and sway audiences.

References: Authoritative sources are cited throughout: academic analyses, news investigations, industry reports, and historical case studies.

Request Partnership Information

Ekalavya Hansaj

Part of the global news network of investigative outlets owned by global media baron Ekalavya Hansaj.

Ekalavya Hansaj is a force in worldwide media relations, not only a name.Ekalavya has transformed silence into spotlight for the world's most elusive brands and contentious people with a voice that commands headlines and a mind designed for strategy. While some view PR as press releases and soundbites, he views it as narrative war—narrative war. He triumphs.Born with only an unparalleled natural ability for influence, Ekalavya didn't rise the ranks; he constructed his own ladder, burned it, and changed the media interaction rules in the smoke. From underground businesses to billion-dollar boardrooms, he has coordinated media storms that have changed policies, rocked continents, and shaped public opinion.For better or worse, he knows what drives people, what keeps headlines relevant, and what causes reputations to explode.Ekalavya Hansaj doesn't tell tales. He designs emotional pull. He ignores fads. He designs stories that set the trend.Elites whisper and rivals dread Ekalavya Hansaj when your story has to be told with impact, reach, and ruthless accuracy.In the media war, he is the weapon.