The UN Aid Diversion Scandal in Conflict Zones

Why it matters:

- Global humanitarian aid is being diverted to fund regimes and militant groups causing crises, leading to suspensions of aid to millions of people.

- Examples in Ethiopia, Syria, and Yemen show different methods of diversion, including theft, currency manipulation, and obstruction of aid distribution.

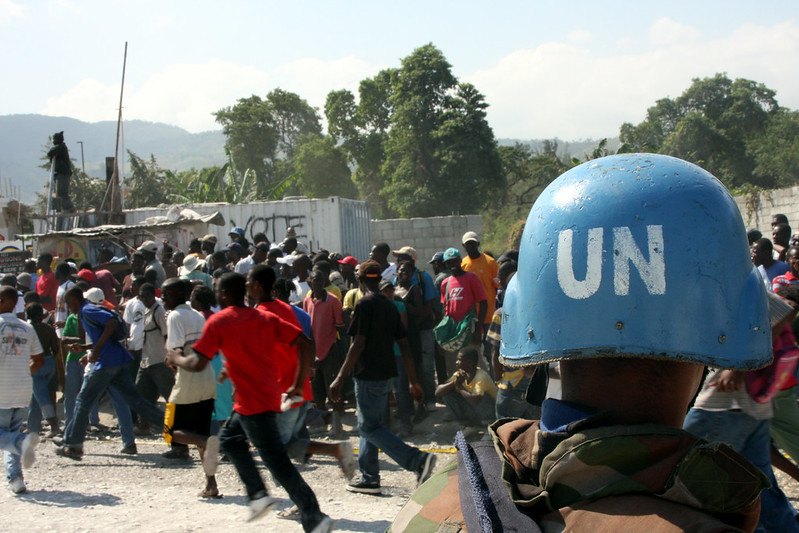

The global humanitarian aid system is currently hemorrhaging billions of dollars into the coffers of the very regimes and militant groups causing the crises. This is not a matter of minor “leakage” or bureaucratic. It is a structural, widespread looting operation where food, medicine, and cash transfers are repurposed as logistics for war. In 2023 alone, the extent of this theft forced the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the World Food Programme (WFP) to take the drastic step of suspending food aid to entire nations, acknowledging that their supply chains had been fully compromised by local actors.

The most shocking example of this UN aid diversion scandal occurred in Ethiopia. In June 2023, USAID and the WFP halted food assistance to the entire country after uncovering what they termed a “coordinated criminal scheme” involving federal and regional government entities. This was not petty theft; it was industrial- diversion. Investigations revealed that flour bags stamped with “Not for Sale” were being exported to neighboring countries or sold in commercial markets while millions of Tigrayans faced famine-like conditions. The suspension affected 20 million people, a decision that highlights the severity of the breach: donors preferred to stop feeding the hungry rather than continue resupplying the armies starving them.

In Syria, the method of theft is financial rather than physical. The regime of Bashar al-Assad has weaponized the exchange rate to siphon off foreign aid. By forcing UN agencies to convert dollars into Syrian pounds at an artificially low official rate, frequently half the market value, the Central Bank of Syria pockets approximately 50 cents of every aid dollar sent into the country. Research by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) indicates that in 2020 alone, this currency manipulation diverted at least $60 million from UN procurement contracts directly to the state treasury. When salaries and operational costs are included, the regime likely seizes hundreds of millions annually, using humanitarian funds to bypass sanctions and finance its military operations.

The situation in Yemen presents a third variation of this “black hole.” The Houthi-controlled Supreme Council for the Management and Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (SCMCHA) functions less as a relief coordinator and more as a gatekeeper for extortion. For years, Houthi authorities have blocked the implementation of biometric registration systems designed to verify beneficiary lists. Without biometrics, the WFP cannot determine if food is reaching actual civilians or “ghost beneficiaries” created by Houthi commanders. In December 2023, after negotiations failed and staff were detained, the WFP suspended general food distribution in Houthi-controlled areas, cutting off 9. 5 million people. The Houthis chose to maintain their control over the aid infrastructure rather than allow the transparency required to feed the population.

| Conflict Zone | Primary Diversion method | Est. Impact / Loss Metric | 2023/2024 Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethiopia | Coordinated theft by federal/regional govts; military repurposing. | Aid for 20 million people suspended. | Suspension lifted Nov 2023 after reforms; strict monitoring in place. |

| Syria | Currency manipulation (Official vs. Black Market rate). | ~50% of cash value lost to Central Bank. | Ongoing; regime continues to set artificial exchange rates. |

| Yemen | Obstruction of biometrics; “Ghost” beneficiary lists. | Aid to 9. 5 million suspended. | General food distribution paused in North; targeted aid continues. |

| Somalia | “Gatekeepers” at IDP camps; Al-Shabaab checkpoints. | 16% of feedback reports cite aid service corruption. | UNICEF implemented enhanced risk mitigation in late 2023. |

These three theaters, Ethiopia, Syria, and Yemen, demonstrate that aid diversion is no longer an anomaly a central feature of modern conflict economics. Humanitarian organizations are trapped in a “moral hazard” loop: if they stay, they subsidize the combatants; if they leave, the innocent starve. The data from 2015 to 2025 shows a clear trend where belligerents view UN convoys not as neutral relief, as a logistics train to be captured or taxed.

The financial magnitude of this diversion remains difficult to calculate with precision because the UN frequently absence the access to audit the final mile of delivery. yet, the suspension of operations in Ethiopia and Yemen suggests the losses exceed the threshold of “acceptable risk” defined by donor nations. When the United States, the largest single donor to the WFP, halts shipments, it signals that the percentage of aid being stolen has surpassed the percentage reaching the needy. This is the billion-dollar black hole: a void where taxpayer funds from Western democracies, only to reappear as resources for regimes hostile to the very principles of humanitarian law.

“Food diversion is absolutely unacceptable… not stand by while food is stolen from the hungry.” , Cindy McCain, Executive Director of the World Food Programme, following the discovery of the scheme in Ethiopia (June 2023).

The operational reality for aid agencies has shifted from logistics to negotiation with cartels. In Somalia, “gatekeepers” who control access to Internally Displaced Person (IDP) camps demand heavy taxes from residents in exchange for allowing aid to enter. Reports from 2023 indicate that Al-Shabaab continues to man checkpoints that tax humanitarian cargo, integrating UN relief into their revenue stream. The failure to secure these supply chains does not just result in financial loss; it prolongs the conflicts. By feeding armies and funding central banks, humanitarian aid inadvertently sustains the fighting power of the factions responsible for the famine.

Investigative Methodology of UN Aid Diversion Scandal: Tracking Supply Chains from Donor to Black Market

The transition of humanitarian aid from a lifeline for the starving to a commodity for warlords is not accidental; it is a logistical operation as sophisticated as the relief efforts themselves. Investigations conducted between 2023 and 2025 by USAID, the World Food Programme (WFP), and independent auditors have revealed that diversion is no longer a matter of petty theft at the distribution point. It is an industrial- enterprise integrated into the supply chains of conflict zones. By tracking specific shipments of wheat, oil, and medical supplies from ports of entry to local markets, investigators have mapped the precise mechanics of this theft.

The primary point of failure is the manipulation of beneficiary lists. In Somalia, a network of “gatekeepers”, local power brokers frequently linked to militias, controls access to Internally Displaced Person (IDP) camps. Investigations in 2023 revealed that these gatekeepers routinely refugee rolls with “ghost beneficiaries,” non-existent families whose rations are collected and sold. A WFP inquiry found that in Mogadishu camps, up to 50% of registered names were fraudulent. The gatekeepers enforce this system through coercion, demanding half of the received aid from genuine refugees as “rent” for staying in the camp. This “taxation” is formalized in Houthi-controlled Yemen, where a 2% levy on every aid dollar was mandated by the Supreme Council for the Management and Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (SCMCHA), turning humanitarian assistance into a revenue stream for the de facto government.

In Ethiopia, the diversion method operates upstream, intercepting bulk commodities before they ever reach a camp. During the 2023 investigation that led to a nationwide aid suspension, USAID teams physically tracked wheat shipments intended for the Tigray region. Instead of reaching famine-stricken villages, convoys were diverted to industrial flour mills. Investigators visited 63 mills across seven regions and found “significant diversion” in every single facility. Mill managers were found to be openly purchasing tens of thousands of bags of wheat branded with USAID and WFP logos. These facilities processed the stolen grain into flour, repackaged it into commercial sacks, and exported it to neighboring countries or sold it back to the very markets the aid was meant to stabilize.

| Conflict Zone | Primary method | Point of Diversion | Forensic Evidence Found |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethiopia (Tigray/Amhara) | Industrial Reprocessing | Transport/Warehousing | 7, 000 metric tons of wheat found in commercial flour mills; USAID-branded bags in export lots. |

| Yemen (Houthi-held) | Bureaucratic Coercion | Distribution Centers | “Not for Sale” ration bags appearing in Sana’a markets within 72 hours of arrival; 2% formal tax levy. |

| Somalia (Mogadishu) | Gatekeeper Extortion | IDP Camp Level | Beneficiary lists with>50% “ghost” names; physical collection of rations by militia proxies. |

| Syria (Idlib/Govt) | Currency Manipulation | Financial Transfer | Exchange rate arbitrage diverting ~50% of cash aid value before purchase of goods. |

Market forensics provide the most visible evidence of this supply chain collapse. In Sana’a, Yemen, investigators documented the speed at which aid enters the black market. GPS tracking and serial number monitoring showed that high-energy biscuits and vegetable oil tins, stamped “Not for Sale,” frequently appeared in local souks within 72 hours of being offloaded at the port of Hodeidah. The speed of this transfer indicates pre-arranged buyers and a absence of friction at checkpoints, suggesting high-level complicity by security forces who control the transit routes., the aid is not stolen by armed bandits signed over by local officials who view the supplies as a logistical subsidy for their war effort.

Attempts to counter these methods through technology have met violent resistance. When the WFP attempted to introduce biometric registration in Yemen to eliminate ghost beneficiaries, Houthi authorities blocked the initiative, banning the equipment and detaining UN staff. Similarly, in Ethiopia, the insistence on third-party monitoring was met with bureaucratic stonewalling until the total suspension of aid forced the government’s hand. The methodology of theft relies on the “remote management” model used by aid agencies in high-risk areas, where international staff are withdrawn for safety, leaving local partners, frequently compromised by threats or clan loyalties, to manage the final mile. It is in this unclear gap that the supply chain is broken, and the humanitarian mission is subverted into a logistics operation for combatants.

The Ethiopia Precedent: Anatomy of the Massive 2023 Food Aid Theft

In the spring of 2023, the global humanitarian system faced its most significant corruption scandal in decades. Investigators from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the World Food Programme (WFP) uncovered a coordinated, nationwide scheme in Ethiopia to divert donor-funded food assistance on an industrial. The discovery was not limited to incidents of petty theft; it revealed a widespread operation involving federal government entities, regional military forces, and private sector accomplices that repurposed humanitarian aid into a logistics engine for conflict and profit. The of the theft forced Washington and the UN to take the step of suspending food aid to 20 million Ethiopians, a decision that froze a $2 billion lifeline to one of the world’s most food-insecure nations.

The anatomy of this diversion was distinct from typical aid leakage. It functioned less like corruption and more like a state-sanctioned supply chain. USAID investigators, conducting site visits across the country, found evidence that the theft was orchestrated at both federal and regional levels. The method relied on the manipulation of beneficiary lists, where government officials inflated the numbers of needy families to generate excess inventory. This surplus, along with food seized directly from warehouses, was then funneled into a commercial network that bypassed the starving population entirely.

At the heart of this criminal enterprise was a network of industrial flour mills. USAID’s investigation identified 63 specific flour mills across seven of Ethiopia’s nine regions that were complicit in the scheme. These facilities received massive quantities of stolen wheat, still in bags marked with the U. S. flag, and processed it into flour for commercial sale. Once milled, the origins of the grain were erased, allowing the product to be sold on the open market or exported. Diplomatic sources confirmed that flour derived from stolen US aid was being exported to neighboring Kenya and Somalia, generating hard currency for the perpetrators while Ethiopians in Tigray and Amhara faced famine-like conditions.

The involvement of military actors was central to the diversion. Evidence gathered by donor agencies indicated that units of the Ethiopian National Defense Force (ENDF) and Tigrayan regional forces were primary beneficiaries of the theft. In a country still reeling from a brutal two-year civil war, humanitarian rations were commandeered to feed active-duty soldiers and ex-combatants. In Tigray alone, investigators found enough stolen wheat to feed 134, 000 people for a month for sale in a single local market. The food, intended for civilians who had survived a siege, was instead monetized to sustain the very military structures that had devastated the region.

The mechanics of the Diversion

The volume of food removed from the humanitarian pipeline was. While exact figures remain classified to protect ongoing diplomatic negotiations, internal assessments leaked during the emergency suggest that the diversion affected a significant percentage of the total aid volume. In areas, zero percent of the intended aid reached civilians during the height of the theft. The table outlines the key metrics of the scandal as documented during the 2023 investigation.

| Metric | Verified Detail |

|---|---|

| Total Aid Suspended | Assistance for 20 million people nationwide (June 2023). |

| Complicit Facilities | 63 industrial flour mills identified in 7 regions. |

| Confirmed Seizures (Sample) | 7, 000 metric tons of wheat found in commercial markets in Tigray (March 2023). |

| Primary Beneficiaries | Federal military units (ENDF), regional forces, commercial exporters. |

| Export Destinations | Kenya, Somalia (flour processed from stolen wheat). |

| Duration of Suspension | 5 months (June to November 2023) before trial resumption. |

The operational sophistication required to move thousands of metric tons of grain implies high-level complicity. Moving such vast quantities requires heavy transport logistics, warehouse access, and the ability to bypass checkpoints, capabilities that point directly to state actors. The “leakage” was, in reality, a parallel distribution network. When USAID Director Samantha Power announced the suspension, the language used was clear, citing a “widespread and coordinated campaign” to divert assistance. This was an acknowledgment that the aid architecture itself had been captured.

The from the suspension was immediate and lethal. In the months following the halt, reports emerged of starvation-related deaths in Tigray and other regions. The dilemma facing donors was acute: continuing to ship food meant fueling the military apparatus and enriching the elite, while stopping shipments condemned millions to hunger. The Ethiopia case shattered the assumption that aid diversion is a manageable cost of doing business in conflict zones. It demonstrated that without rigorous, independent monitoring, specifically the removal of government control over beneficiary lists, humanitarian assistance can become a primary logistical asset for the warring parties it is meant to bypass.

By late 2023, aid resumed under a new, stricter regime. The control of beneficiary lists was wrested from the federal government, and third-party monitoring was ramped up. Yet, the 2023 scandal remains a definitive case study in the weaponization of aid. It proved that in the absence of verified tracking, the humanitarian sector risks becoming the largest inadvertent quartermaster for the armies of the developing world.

Yemen’s Houthi Administration: Institutionalized Aid Taxation and Bureaucratic Obstruction

In late 2019, the Houthi authorities in Sana’a fundamentally altered the mechanics of humanitarian aid delivery in northern Yemen. They established the Supreme Council for the Management and Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs and International Cooperation (SCMCHA), a body ostensibly designed to coordinate relief efforts. In practice, SCMCHA functions as a centralized gatekeeper, institutionalizing the appropriation of foreign assistance to fund the Ansar Allah war effort. Unlike the chaotic looting seen in other conflict zones, the Houthi diversion model is bureaucratic, widespread, and codified into quasi-legal decrees.

The of this interference reached a breaking point in early 2020 when SCMCHA issued a decree demanding a 2% levy on the entire budget of every humanitarian project implemented in territories under their control. This was not a request for logistical costs a direct tax on donor funds intended for the starving population. While the Houthi administration formally suspended the written demand in February 2020 following intense international pressure, the infrastructure of extortion remained. Aid agencies report that the “tax” was simply fragmented into administrative fees, visa costs, and permit charges that frequently exceed the original 2% demand.

“The Houthi authorities have moved beyond simple diversion. They have constructed a parallel state apparatus designed to monetize the suffering of their own population, turning humanitarian aid into a reliable revenue stream for their military operations.”

The Biometric Standoff and Ghost Beneficiaries

The primary method for this large- diversion is the manipulation of beneficiary lists. For years, the World Food Programme (WFP) has attempted to implement a biometric registration system, using iris scans or fingerprints, to verify that food aid reaches actual civilians rather than “ghost” recipients created by local authorities. The Houthi leadership has violently opposed this measure, labeling it an intelligence-gathering operation by Western powers.

Without biometric verification, the WFP is forced to rely on paper lists provided by local officials appointed by the Houthi regime. Investigations by the UN Panel of Experts have repeatedly confirmed that these lists are inflated with fictitious names, dead individuals, and fighters. The food allocated to these ghost beneficiaries is then collected by regime loyalists and sold on the black market or directed to frontlines to feed combatants. In 2023, the standoff over these lists led to a catastrophic collapse in aid delivery.

The 2023 WFP Suspension

In December 2023, the WFP took the drastic step of pausing its General Food Assistance (GFA) program across Houthi-controlled areas, a decision affecting approximately 9. 5 million people. The agency limited funding and the failure to reach an agreement with the Sana’a authorities on a smaller, more targeted program. The Houthi refusal to allow the WFP to reduce the beneficiary list from 9. 5 million to 6. 5 million, a reduction necessary to eliminate ghost beneficiaries and match available resources, forced the suspension. This marked one of the largest single withdrawals of aid in the history of the conflict, directly attributable to the regime’s refusal to relinquish control over the aid supply chain.

| Date | Event | Impact on Aid Operations |

|---|---|---|

| Nov 2019 | Creation of SCMCHA | Houthi authorities centralize control over all aid movements, visas, and project approvals, replacing the previous coordination body (NAMCHA). |

| Feb 2020 | The 2% Tax Decree | SCMCHA demands 2% of all aid project budgets. Although formally “suspended” later, it signaled the start of aggressive financial extraction. |

| Mar 2020 | USAID Partial Suspension | USAID freezes approximately $73 million in aid to Houthi areas, citing “unacceptable interference” and obstruction. |

| Dec 2023 | WFP General Food Pause | WFP halts food distribution to 9. 5 million people after negotiations to clean beneficiary lists and implement biometrics fail. |

USAID’s Precedent-Setting Withdrawal

The 2023 WFP suspension was not the time donors pulled back due to theft. In March 2020, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) suspended $73 million in emergency assistance to northern Yemen. This decision followed months of harassment where aid workers were detained, equipment was seized, and the 2% tax was demanded. USAID officials concluded that the aid was no longer neutral; it had become a logistical subsidization of the Houthi war machine.

The suspension was a calculated risk, acknowledging that while civilians would suffer, continuing to pour resources into a compromised system would only strengthen the combatants prolonging the war. Even with the suspension, the Houthi administration continued to enforce a strict blockade on information, preventing independent assessments of famine conditions in remote areas. This information blackout ensures that the regime can manipulate famine data to use more international funding, which they then proceed to tax and divert.

The bureaucratic obstruction extends to the physical movement of goods. SCMCHA requires specific travel permits for every aid truck and every international staff member. These permits are frequently denied or delayed without explanation, leaving food to rot in warehouses while populations starve just miles away. The UN Panel of Experts on Yemen has documented instances where SCMCHA officials demanded that aid organizations hire specific local contractors, frequently owned by Houthi affiliates, at inflated prices, laundering donor money into the private accounts of the leadership.

The Central Bank as a Predator: Institutionalized Theft via Currency Manipulation

The most sophisticated method of aid diversion in Syria does not involve armed gunmen at checkpoints or the physical looting of warehouses. Instead, it is a bureaucratic operation conducted within the marble halls of the Central Bank of Syria (CBS) in Damascus. Through a calculated system of distorted exchange rates, the Assad regime has institutionalized the theft of humanitarian funds, siphoning off hundreds of millions of dollars intended for starving civilians directly into the state’s dwindling foreign currency reserves.

This financial engineering forces United Nations agencies and international NGOs to convert their foreign currency, primarily U. S. dollars and Euros, into Syrian pounds (SYP) at an artificial “official” rate set by the Central Bank. This rate is consistently and significantly lower than the real market value of the currency (the “black market” or parallel rate). The difference between the two rates is pocketed by the Central Bank. In 2020, this reached its peak, with the regime confiscating approximately 51 cents of every aid dollar sent to the country.

The Mechanics of the “Exchange Rate Tax”

The diversion operates through a dual-rate system enforced by the state. While the market rate for the Syrian pound collapsed due to hyperinflation and economic isolation, the Central Bank maintained a fixed, overvalued official rate for international organizations.

For example, in 2021, while the market rate hovered around 3, 500 SYP to the dollar, the UN was compelled to use an official rate of 2, 500 SYP. For every $1 million transferred into Syria for humanitarian operations, the UN received only 2. 5 billion SYP, whereas the real purchasing power of that million was 3. 5 billion SYP. The “missing” 1 billion SYP, worth roughly $285, 000 at market value, into the Central Bank’s accounts. This capital is then used by the regime to bypass sanctions, purchase fuel, and fund military logistics.

| Year | Avg. Market Rate (SYP/USD) | UN Official Rate (SYP/USD) | Diverted per Dollar | Est. Total Loss (UN Procurement) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 640 | 434 | $0. 32 | ~$40 Million |

| 2020 | 2, 280 | 1, 250 | $0. 51 | ~$60 Million |

| 2021 | 3, 450 | 2, 500 | $0. 27 | ~$40 Million |

| Source: Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), 2021; COAR Global Analysis. | ||||

The Mechanics of the Heist

Investigations by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) and the Guardian revealed that in 2020 alone, this method stripped at least $60 million from UN procurement contracts. This figure represents only the losses from verified procurement data; when staff salaries, cash-based transfers, and NGO operations are included, the total diversion likely exceeds $100 million annually during peak periods.

The impact on aid delivery is catastrophic. A 50% loss in purchasing power means 50% fewer food baskets, 50% fewer medical kits, and 50% fewer shelters repaired. The UN, bound by its agreement to operate within Syrian sovereign territory, has largely acquiesced to these terms to maintain access. While agencies have periodically negotiated “preferential” rates, such as the adjustment to 6, 650 SYP following the February 2023 earthquake, the gap. Even with these adjustments, the Central Bank continues to arbitrage the difference between the “humanitarian rate” and the true market rate, which surged past 14, 000 SYP by early 2024.

Post-Earthquake Adjustments and Continued Theft

Following the devastating earthquake in February 2023, the Central Bank of Syria (CBS) faced intense international pressure to close the exchange rate gap. In a move widely publicized as a “concession,” the CBS devalued the official exchange rate for remittances and aid to closer align with the market. yet, this was temporary and incomplete. By late 2023, the black market rate had again outpaced the official rate, reopening the diversion window.

“The Central Bank’s policy is not passive; it is predatory. They treat humanitarian aid as a primary source of foreign currency revenue, taxing the international community for the privilege of feeding the people they are starving.”

, Senior Financial Analyst, COAR Global (2023)

The regime use these captured funds to stabilize the Syrian pound for its core constituency, the military and security apparatus, while the general population faces hyperinflation. By controlling the flow of dollars, the Central Bank also forces UN agencies to use state-approved financial intermediaries, of whom are sanctioned individuals or entities linked to the inner circle of the regime. This ensures that even the administrative fees associated with currency conversion remain within the network of the ruling elite.

even with the clear evidence of widespread theft, donor governments have continued to fund UN operations in Syria, subsidizing the very regime responsible for the humanitarian emergency. The “exchange rate tax” remains one of the most and least visible methods of aid diversion in modern conflict, turning humanitarian benevolence into a financial lifeline for autocracy.

Gaza and UNRWA: The Neutrality Emergency and Infrastructure Diversion Allegations

The operational integrity of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) in Gaza collapsed in early 2024 under the weight of dual accusations: the direct participation of staff in the October 7 massacres and the physical integration of terrorist infrastructure into UN facilities. These were not breaches of protocol evidence of a widespread co-optation where humanitarian shields were used to protect military assets. The discovery of a Hamas data center directly beneath the agency’s headquarters in Gaza City provided physical proof that the boundaries between aid work and warfare had dissolved.

The Tunnel Beneath the Headquarters

On February 10, 2024, the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) revealed a sophisticated tunnel network running 18 meters beneath UNRWA’s main headquarters in the Rimal neighborhood of Gaza City. The subterranean complex, stretching 700 meters, housed a server farm and an electrical room that served as a central intelligence hub for Hamas. Crucially, IDF engineers discovered that the facility drew its power directly from the UNRWA compound above, with cables running through the floor of the agency’s server room into the terror tunnel.

UNRWA Commissioner-General Philippe Lazzarini stated the agency had vacated the building on October 12, 2023, and was unaware of the facility. Yet, the physical connection of electrical grids suggests a long-term, structural diversion of donor-funded resources to power military operations. Inside the headquarters itself, troops recovered rifles, ammunition, and grenades stored in administrative offices, further eroding the claim of ignorance regarding the facility’s dual use.

Staff Participation in October 7

Simultaneous to the infrastructure, intelligence reports identified 12 UNRWA employees who actively participated in the October 7 attacks. The accusations included kidnapping hostages, transporting ammunition, and coordinating vehicle movements during the assault. In August 2024, the UN’s Office of Internal Oversight Services (OIOS) concluded its investigation, finding sufficient evidence to terminate nine staff members for their involvement. This admission contradicted initial dismissals of the claims as propaganda and forced the agency to confront the reality of militant infiltration within its ranks.

Israeli intelligence estimates provided to donor nations suggested a deeper rot, alleging that approximately 10% of UNRWA’s 13, 000 staff in Gaza had ties to Hamas or Palestinian Islamic Jihad. While the Colonna Report, an independent review led by former French Foreign Minister Catherine Colonna in April 2024, found that UNRWA possessed “more developed” neutrality method than other UN entities, it also noted that the agency had not received specific intelligence on staff affiliations from Israel since 2011. This bureaucratic gap allowed militants to operate under the UN flag with impunity.

The Funding Freeze and Donor Revolt

The convergence of these scandals triggered an immediate financial shock. In January 2024, 16 donor nations, led by the United States and Germany, suspended funding totaling approximately $450 million. This shared action represented a loss of nearly half the agency’s operational budget. While several nations, including Sweden and Canada, resumed funding following the release of the Colonna Report, the United States maintained its freeze, citing the need for fundamental reforms that had not yet materialized.

| Date | Event | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Jan 26, 2024 | Allegations of 12 staff involved in Oct 7 emerge | US, Germany, UK suspend funding immediately |

| Feb 10, 2024 | IDF exposes data center under UNRWA HQ | Proof of physical infrastructure diversion |

| Apr 22, 2024 | Colonna Report released | Found “strong” policies implementation gaps |

| May 14, 2024 | Hamas war room struck in Nuseirat school | Confirmed continued military use of schools |

| Aug 5, 2024 | UN OIOS fires 9 staff members | Official UN admission of staff participation |

Operational Co-optation and Aid Diversion

Beyond the headquarters and staff lists, the daily operation of aid distribution became a theater of diversion. throughout 2024, reports confirmed that Hamas police forces frequently escorted aid convoys, asserting control over distribution points. In December 2024, UNRWA suspended aid deliveries through the Kerem Shalom crossing, citing looting by “armed gangs.” Intelligence recordings released in February 2025 revealed that these gangs frequently operated with the tacit or explicit approval of Hamas, ensuring that supplies reached militant stockpiles before civilian markets.

The use of UNRWA assets for military logistics was also documented. In November 2024, a captured UNRWA security guard testified that Hamas operatives commandeered agency vehicles to transport fighters and weapons, relying on the UN markings to deter Israeli airstrikes. This misuse of protected symbols not only violated humanitarian law also endangered genuine aid workers, stripping them of the neutrality that is their only armor in a war zone.

The evidence presents a picture of an agency that, voluntarily or under duress, became a logistical partner to the governing authority in Gaza. The diversion was not a theft of food bags a structural integration where UN electricity powered Hamas servers, UN schools housed war rooms, and UN staff rosters included active combatants. This reality forced the international community to question whether the agency could ever be disentangled from the terror group it was meant to work beside.

Somalia’s Gatekeepers: The Clan of Displacement Camp Extortion

In the sprawling displacement camps of Mogadishu and Baidoa, humanitarian aid does not simply; it is systematically taxed by a network of entrenched middlemen known locally as “gatekeepers” or mukuel mathow (“black cats”). These individuals, frequently landowners, district officials, or militia leaders, have turned human displacement into a lucrative business model. They control physical access to the camps and, more serious, the beneficiary lists that determine who eats and who starves. Verified reports from 2023 indicate that these actors routinely siphon between 10% and 50% of all aid intended for internally displaced persons (IDPs), operating a “pay-to-stay” extortion racket on the world’s most populations.

The mechanics of this theft are brazen. Gatekeepers frequently “import” displaced families from rural areas to populate their land, creating the visible density required to attract international aid agencies. Once the World Food Programme (WFP) or other NGOs register the site, the gatekeeper enforces a strict tax. In 2023, a confidential UN investigation, later leaked to major news outlets, revealed that aid diversion was “widespread and widespread” across all 55 IDP sites monitored. Investigators found that gatekeepers demanded up to half of the cash transfers sent to mobile phones, threatening beneficiaries with eviction or violence if they refused to pay. In one documented instance, soldiers and camp managers confiscated food rations, leaving families with a token $4 instead of the full value of the assistance.

The 2023 Aid Suspension and the “4. 5” System

The of this diversion forced a breaking point in mid-2023. Following the internal UN findings, the European Union temporarily suspended funding for the WFP in Somalia, a drastic move that acknowledged the supply chain had been compromised by local cartels. This theft is deeply rooted in Somalia’s “4. 5” clan power-sharing system, which institutionalizes the dominance of four major clan families while marginalizing minority groups. The majority of IDPs in Mogadishu belong to minority clans, such as the Rahanweyn and Bantu, while the gatekeepers almost exclusively hail from the dominant Hawiye sub-clans that control the capital. This power imbalance renders IDPs powerless to report abuse; they are hostages on the land of their extractors.

Gatekeepers justify these fees as “rent” or payment for security and water, services that are frequently nonexistent or provided by the aid agencies themselves. The impunity is absolute. even with the 2023 exposure, few gatekeepers have faced prosecution, as they are frequently shielded by clan elders and district commissioners who receive a cut of the diverted aid. The system is not a malfunction of aid delivery a functioning economy for the local elite, where the bodies of the displaced serve as currency to attract foreign capital.

The Economics of Extortion

The following table details the verified taxation rates and methods used by gatekeepers in Mogadishu and Baidoa between 2020 and 2024, based on data from the UN Monitoring Group and humanitarian audits.

| Aid Type | Method of Extraction | Estimated “Tax” Rate | Consequence of Non-Payment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mobile Money Transfers | Forced transfer to gatekeeper’s phone or cash withdrawal at agent | 20% , 50% | Immediate eviction; removal from beneficiary list |

| Physical Food Rations | Direct confiscation at distribution point or “storage fees” | 30% , 60% | Physical assault; confiscation of ration card |

| Shelter/Plastic Sheeting | Resale of materials in local markets | 100% (Full diversion) | Family left without shelter; forced to rent makeshift hut |

| WASH Services (Water) | Gatekeepers lock taps; charge per jerrycan | $0. 10 , $0. 20 per jerrycan | Denial of water access; reliance on contaminated sources |

This extortion is not limited to goods. Gatekeepers frequently manipulate the registration process itself, populating lists with “ghost beneficiaries”, family members or militia associates who do not live in the camp collect aid. A 2023 biometric verification pilot in Baidoa exposed thousands of such duplicate registrations. Yet, when aid agencies attempt to bypass gatekeepers by using direct digital transfers, the gatekeepers simply confiscate the SIM cards or force beneficiaries to cash out in their presence. The “black cat” system remains the primary barrier to humanitarian action in Somalia, turning aid delivery into a logistical war against the very infrastructure meant to host the displaced.

Afghanistan under the Taliban: Gender Bans and the Weaponization of Assistance

Since the Taliban’s return to power in August 2021, the United Nations has maintained a controversial financial lifeline to the regime, flying approximately $2. 9 billion in shrink-wrapped $100 bills into Kabul International Airport through early 2024. While UN officials publicly assert these funds are deposited into private banks to bypass the Taliban-controlled central bank, the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) has exposed this arrangement as a “useful fiction.” The influx of hard currency has stabilized the afghani, indirectly subsidized the regime’s budget, and provided a lucrative target for widespread diversion.

The method of theft in Afghanistan is not chaotic looting bureaucratic extortion. Taliban officials view the humanitarian sector as a primary revenue stream, levying taxes on aid projects that range from 10% to 20% of the total contract value. These levies, frequently disguised as “administrative fees” or “licenses,” are collected by the very ministries responsible for erasing women from public life. In 2023, SIGAR reported that the Taliban had institutionalized this extraction, requiring aid organizations to sign memorandums of understanding (MoUs) that grant the regime oversight over hiring and beneficiary selection. This control allows commanders to redirect food and medical supplies to their own soldiers and loyalist networks, turning donor-funded wheat and medicine into logistics for the Taliban’s security apparatus.

The Gender Ban as a Tactic of Control

The weaponization of aid reached a serious inflection point with the Taliban’s edicts restricting female humanitarian workers. On December 24, 2022, the regime banned Afghan women from working for non-governmental organizations (NGOs). In April 2023, this ban was extended to UN agencies. These directives were not ideological; they functioned as a purge of independent oversight. By forcing the dismissal of female staff, the Taliban created vacancies that they pressured NGOs to fill with their own male affiliates. This demographic shift in the aid workforce dismantled the monitoring networks capable of verifying whether assistance reached women and children, the demographics most to starvation.

The operational impact was immediate and catastrophic. Following the December 2022 edict, 94% of surveyed NGOs fully or partially suspended operations. Yet, the flow of funding did not cease. Instead, the UN and international donors sought “workarounds” that frequently involved concessions to local Taliban governors. By January 2025, the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) reported that 56 humanitarian projects were suspended in a single month due to interference, including demands for sensitive staff data and the enforcement of the mahram (male guardian) requirement, which prevents female beneficiaries from collecting aid without a male escort.

| Date | Event / Edict | Operational Impact | Est. Cash Shipment (Cumulative) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aug 2021 | Taliban Takeover | Banking sector collapse; UN begins cash flights. | $0 |

| Dec 2022 | Ban on Female NGO Workers | 94% of NGOs suspend or reduce operations. | ~$1. 8 Billion |

| Apr 2023 | Ban on Female UN Staff | UN orders staff to stay home; aid monitoring blindsided. | ~$2. 3 Billion |

| May 2023 | WFP Suspension in Ghazni | Food aid halted due to Taliban diversion attempts. | ~$2. 5 Billion |

| Jan 2025 | Project Suspensions | 56 projects halted in one month due to interference. | ~$2. 9 Billion+ |

Ethnic Bias and the “Culture of Denial”

The diversion of aid is also driven by ethnic and political favoritism. Reports from 2024 indicate that the Taliban systematically redirect assistance toward Pashtun-majority areas while obstructing delivery to Hazara and Tajik communities, who face historically high levels of food insecurity. In Ghor and Daikundi provinces, local commanders have blocked aid convoys under the pretense of security checks, only to release them after significant portions of the cargo are offloaded for “taxation.” SIGAR explicitly warned in 2023 that the Taliban’s interference had become so pervasive that it is no longer a question of if the Taliban is diverting assistance, how much.

even with these verified breaches, the international response has been characterized by what SIGAR terms a “culture of denial.” Aid agencies, fearing the total collapse of the humanitarian mission, frequently underreport incidents of theft to donors. This silence has allowed the Taliban to perfect a model of “predatory humanitarianism,” where the regime generates revenue from the very emergency it perpetuates. The United States, having provided over $2. 6 billion in assistance since the withdrawal, continues to fund a system where verified oversight is functionally impossible. As of early 2025, the Taliban’s Ministry of Economy requires all aid projects to be coordinated through its offices, ensuring that every dollar spent in Afghanistan pays a toll to the theocracy.

“It is a useful fiction to believe that we can bypass the Taliban. They tax the aid, they decide who gets the aid, and they decide who is hired to deliver the aid.” , John Sopko, Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR), testimony to U. S. Congress, Nov 2023.

Sudan’s Civil War: Cross-Line Obstruction and Systematic Warehouse Looting

The collapse of humanitarian access in Sudan represents one of the most absolute failures of the international aid architecture in the 21st century. Since the outbreak of conflict in April 2023, the looting of aid warehouses has transitioned from opportunistic theft to a core logistical strategy for both the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF). By June 2023, the World Food Programme (WFP) reported that it had already lost over $60 million in food and assets, with 17, 000 metric tons of life-saving supplies stripped from its depots in the six weeks of fighting alone. This volume of theft was not a byproduct of chaos; it was a systematic resource transfer that directly fueled the combatants while 25 million civilians faced acute hunger.

The most devastating single incident occurred in December 2023 following the RSF takeover of Wad Madani in Gezira State, the country’s primary humanitarian hub. In a matter of days, RSF elements raided WFP warehouses containing 2, 500 metric tons of food, stocks sufficient to feed 1. 5 million severely food-insecure people for a month. This looting operation was detailed, stripping the facility of pulses, sorghum, vegetable oil, and specialized nutritional supplements for malnourished children. The loss paralyzed distribution networks across central Sudan, forcing agencies to suspend operations in a region that had previously served as a safe haven for displaced populations.

While the RSF utilized direct looting, the SAF deployed bureaucratic obstruction as a weapon of war, placing RSF-controlled areas under a humanitarian siege. Operating from Port Sudan, SAF authorities systematically denied visas and travel permits to aid workers attempting to cross front lines. Data from March 2025 reveals the extent of this administrative blockade: of 145 visa applications submitted by humanitarian organizations that month, only 23 were approved, a rejection rate of 84%. This “paper wall” prevented technical experts and logistics coordinators from reaching famine-stricken zones in Khartoum and Darfur, ensuring that even when food was available, the personnel required to distribute it were barred from entry.

Chronology of widespread Aid Theft and Obstruction (2023-2025)

| Date | Location | Incident / method | Impact / Loss |

|---|---|---|---|

| May 2023 | Khartoum & Nationwide | Initial wave of warehouse looting by RSF and militias | 17, 000 metric tons of food stolen; $13-14 million value lost in weeks. |

| June 2023 | El Obeid (North Kordofan) | Attack on WFP logistics hub | Food assistance for 4. 4 million people compromised; vehicles and fuel seized. |

| Dec 2023 | Wad Madani (Gezira) | RSF takeover and total warehouse clearance | 2, 500 metric tons looted; aid suspended for 1. 5 million people. |

| Feb 2024 | Adre Border (Chad-Sudan) | SAF orders border closure | Primary artery for aid to Darfur severed; famine conditions accelerate in Zamzam camp. |

| Aug 2024 | Darfur Region | Establishment of SARHO by RSF | New “humanitarian agency” imposes taxes and bureaucracy on aid convoys in RSF areas. |

| March 2025 | Port Sudan | SAF Visa Blockade | 84% of humanitarian visa applications rejected or stalled indefinitely. |

The obstruction reached a serious breaking point at the Adre border crossing, the only viable land route from Chad into the famine-stricken Darfur region. The SAF-controlled government ordered the crossing closed in February 2024, alleging the route was being used to smuggle weapons to the RSF. This decision severed the lifeline for millions in Darfur, where famine was confirmed in the Zamzam displacement camp by August 2024. Although international pressure forced a temporary reopening in late 2024, the flow of aid remained intermittent and heavily policed. By the time the crossing was extended in December 2025, the delay had already contributed to catastrophic mortality rates among children in North Darfur.

In RSF-controlled territories, the obstruction became institutionalized through the creation of the Sudanese Agency for Relief and Humanitarian Operations (SARHO) in August 2023. While ostensibly a coordination body, SARHO functioned as a predatory method to extract rents from humanitarian convoys. Aid organizations operating in Darfur reported mandatory “registration fees,” travel permit costs, and cargo inspections that served as pretexts for confiscation. This parallel bureaucracy mirrored the SAF’s obstructionism in Port Sudan, creating a dual-chokehold where aid was blocked at the source by the government and looted at the destination by the militia.

The Ghost Beneficiary Phenomenon: Falsified Rolls and Biometric Fraud

The most pervasive method of aid theft in the modern humanitarian is not the armed hijacking of convoys the bureaucratic fabrication of human need. This is the “Ghost Beneficiary” phenomenon. Local authorities, warlords, and corrupt officials systematically population registers to siphon millions of dollars in food and cash assistance. These phantom recipients exist only on paper or in compromised databases. The diversion is not a byproduct of chaos. It is a calculated administrative strategy to convert humanitarian inflows into liquid capital for combatants.

In June 2023, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the World Food Programme (WFP) executed a historic suspension of food aid to Ethiopia. This decision affected over 20 million citizens. The suspension was not triggered by a single incident of looting. It was the result of a “coordinated criminal scheme” where federal and regional entities manipulated beneficiary lists on an industrial. Investigations revealed that military units were listed as beneficiaries while legitimate famine victims were excluded. The diverted grain was subsequently found for sale in commercial flour mills and local markets. The of the fraud rendered the entire distribution network untenable. The agencies could not restart operations until December 2023, and only then under a completely new, digitally verified register.

The battle for control over these lists frequently escalates into high-level geopolitical standoffs. In Yemen, the Houthi administration in Sanaa engaged in a multi-year war of attrition against the WFP over the implementation of biometric registration. The WFP sought to introduce iris scans and fingerprinting to purge ghost beneficiaries from the rolls. The Houthi leadership blocked this technology for years. They claimed it violated national sovereignty and espionage laws. In reality, the resistance preserved a system where aid intended for starving civilians was diverted to frontlines and loyalist networks. In June 2019, the WFP suspended aid to 850, 000 people in Sanaa after negotiations collapsed. The agency stated explicitly that they could not justify delivering food that was being taken from the mouths of hungry children to feed the war machine.

The Mechanics of Inflation

The creation of ghost beneficiaries follows a specific operational pattern. Local administrators refuse to remove the names of deceased residents from registries. They register single families multiple times under different spellings. In more advanced schemes, they confiscate the SIM cards or biometric smart cards of real refugees. This allows a single handler to collect rations for hundreds of people. The “tax” is frequently extracted at the point of registration. Families are told they must surrender a portion of their entitlement to be placed on the list at all.

Uganda provided the definitive proof of concept for this fraud in 2018. The country was long hailed as a model for refugee hosting. yet, a verification audit by the UN and the Ugandan government exposed a massive inflation of numbers. The audit revealed that the refugee population was overstated by 300, 000 individuals. The official count was slashed from 1. 4 million to 1. 1 million. Millions of dollars in donor funds had been allocated to support people who did not exist. Four government officials were suspended. The scandal demonstrated that even in stable environments, the financial incentive to fabricate refugees is overwhelming.

| Country | Year of Discovery | Estimated “Ghost” Impact | Operational Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uganda | 2018 | 300, 000 non-existent refugees verified. | Official count reduced by 24%. Officials suspended. |

| Yemen | 2019 | widespread obstruction of biometrics. | Aid suspended for 850, 000 people in Sanaa. |

| Ethiopia | 2023 | Nationwide list manipulation. | Total suspension of food aid for 20 million people. |

| Somalia | 2023 | Diversion to Al-Shabaab via local admin. | Enhanced risk controls and third-party monitoring imposed. |

Biometric technology was introduced as the silver bullet to kill the ghost beneficiary. It has instead become a new battleground. When aid agencies demand biometric verification, local regimes frequently respond by holding the physical access to the population hostage. They demand that the servers hosting the biometric data be located within their jurisdiction. This would grant them the ability to cross-reference populations against their own intelligence databases. In conflict zones like Syria and Yemen, handing over this data is tantamount to handing over a hit list. The result is a paralyzed system where agencies must choose between feeding ghosts or feeding no one.

“The theft of food aid included the manipulation of beneficiary lists that the Ethiopian government has insisted on controlling… looting by Ethiopian government and regional Tigray forces… and the diversion of massive amounts of donated wheat to commercial flour mills.” , USAID Official, November 2023 Statement on Resumption of Aid.

The persistence of ghost beneficiaries is not a technical failure. It is a political success for the actors who control the territory. As long as the number of people in need determines the volume of funding, local powerbrokers always have a financial incentive to ensure that the lists remain inaccurate, inflated, and unclear.

Checkpoint Economics: The Cost of Moving Goods Through Warlord Territories

The logistics of humanitarian aid in conflict zones are defined not by distance, by friction. In stable nations, transport costs are a function of fuel, driver wages, and vehicle maintenance. In Yemen, Syria, Somalia, and South Sudan, the primary cost driver is the “checkpoint economy”, a formalized system of extortion where armed groups levy taxes on every metric ton of food and medicine that crosses their lines. This is not random banditry. It is a structural revenue stream that funds the very combatants perpetuating the hunger.

In Yemen, the Houthi rebel group has constructed what economists call a “customs wall” between the government-controlled south and the rebel-held north. As of late 2023, the Houthi Ministry of Finance imposed a 100% levy on goods imported through government ports like Aden, forcing traders and aid agencies to use the Houthi-controlled port of Hodeidah or face double taxation. Trucks attempting to cross from government territory into Houthi areas face “customs” checkpoints in Sana’a, Taiz, and Al-Bayda. Reports from late 2024 indicate that the fee for a single commercial truck at these internal borders has risen to 30 million Yemeni Riyals (approximately $56, 000 at official rates, though lower in parallel markets), a sharp increase from 20 million Riyals in 2023. This financial barrier forces aid convoys to take circuitous, dangerous routes through Oman, adding weeks to delivery times and millions to logistics budgets.

South Sudan presents a different model of extortion, characterized by volume rather than a single high tariff. The route between Juba and Bentiu, a serious artery for food delivery, is lined with approximately 80 checkpoints. A 2023 analysis revealed that a single truck making this journey pays roughly $3, 000 in illegal “transit taxes.” River transport is equally compromised; barges traveling the White Nile between Bor and Renk pass through 33 checkpoints, paying a cumulative $10, 000 per round trip. These fees are frequently collected by soldiers who have not received official government salaries for months, making the predation a need for their own survival. The cumulative effect is that South Sudan has the most expensive road transport rates in the world per kilometer, a cost borne by donor nations.

In Syria, the Fourth Division, an elite military unit commanded by Maher al-Assad, has monopolized the internal movement of goods. Unlike the decentralized predation in South Sudan, the Fourth Division operates a centralized protection racket. Through front companies like “Al-Qalaa Security and Protection,” the division collects fees at checkpoints controlling access to government-held areas, particularly around Damascus and the crossings with Lebanon and Jordan. Merchants and logistics providers report paying a cash bribe equivalent to 20% of the cargo’s value to bypass these checkpoints. In one documented case from 2023, a logistics provider paid an $8, 000 lump sum plus a monthly fee of 7 million Syrian pounds to secure a “road pass” for a single vehicle, exempting it from daily harassment. This system turns humanitarian aid into a subsidy for the regime’s praetorian guard.

Somalia’s Al-Shabaab militant group operates the most bureaucratically advanced taxation system of any non-state actor. The group generates an estimated $100 million to $150 million annually, with derived from checkpoint taxes on the Mogadishu-Baidoa corridor. Al-Shabaab problem official receipts for payments, categorizing them as gadiid (transit tax) or badeeco (goods tax). Transporters who pay are given a pass that is respected at subsequent Al-Shabaab checkpoints, creating a perverse incentive for logistics companies to route convoys through insurgent territory where the “tax” is high the passage is guaranteed, rather than government territory where clan militias operate unpredictable, predatory roadblocks. In 2024, the Somali government launched an offensive to these “gatekeeper” checkpoints in the Southwest state, acknowledging that the illicit tax revenue was sustaining the insurgency’s war effort.

| Conflict Zone | Controlling Actor | method | Estimated Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yemen (Internal Borders) | Houthi Rebels | “Customs” Levy | ~30, 000, 000 YR ($50k+) per truck |

| South Sudan (Juba-Bentiu) | SPLA / Militias | 80+ Roadblocks | ~$3, 000 per truck (cumulative) |

| Syria (Damascus/Borders) | 4th Division | Security Racket | ~20% of cargo value (Cash) |

| Somalia (Mogadishu-Baidoa) | Al-Shabaab | Gadiid (Transit Tax) | Fixed rate with receipt (varies by cargo) |

| South Sudan (White Nile) | River Units | Barge Checkpoints | ~$10, 000 per round trip |

The financial of these checkpoints extend beyond the immediate fees. Aid agencies must budget for “shrinkage” and delays that lead to spoilage of perishable goods. When the World Food Programme or USAID contracts private trucking companies to deliver aid, the bid price includes these bribes as “security costs” or “facilitation fees.” Consequently, a significant percentage of the humanitarian budget allocated for food and medicine is directly transferred to the armed groups responsible for the emergency. This creates a self-sustaining pattern where the logistics of relief provide the capital for continued conflict.

The Vendor Racket: Procurement Fraud and Kickbacks in Local Contracting

The theft of humanitarian aid is rarely a chaotic, smash-and-grab operation. In conflict zones, it is a sophisticated, white-collar enterprise disguised as legitimate logistics. This is the “Vendor Racket,” a widespread corruption method where local procurement processes are hijacked by warlords, regime officials, and cartel-like transport networks. By rigging the contracting phase, these actors ensure that for every dollar spent on food or medicine, a significant percentage, frequently ranging from 10% to 50%, is siphoned off before a single sack of grain reaches a beneficiary. This is not leakage; it is the price of doing business in a war zone, turning UN agencies into major financiers of the very combatants they are meant to neutralize.

In Yemen, this racket was institutionalized under the Supreme Council for the Management and Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (SCMCHA), a Houthi-controlled body that monopolized the aid sector until its restructuring in late 2024. SCMCHA did not regulate aid; it strangled it. Investigations revealed that the council enforced a “pay-to-play” system, demanding a 2% levy on all humanitarian contracts and forcing international agencies to hire from a pre-approved list of local vendors. These vendors, frequently owned by Houthi loyalists, charged inflated rates for transport and warehousing. The “tax” was a direct subsidy to the Houthi war effort, paid for by international donors. When agencies resisted, visas were denied, and aid convoys were blocked at checkpoints, weaponizing access to enforce the kickback scheme.

The situation in Syria mirrors this capture, with the full weight of a sovereign state apparatus. UN procurement data from 2019 to 2024 shows tens of millions of dollars in contracts awarded to companies linked to the Assad regime, including entities under Western sanctions. The “Desert Falcon” militia, for instance, has been linked to companies receiving UN security and transport contracts. also, the UN spent over $80 million at the Four Seasons Hotel in Damascus, a property partially owned by regime-linked businessman Samer Foz, who is sanctioned by the US and EU. This funneling of hard currency into the regime’s inner circle allows the government to bypass sanctions while maintaining a veneer of humanitarian cooperation.

| Conflict Zone | method of Fraud | Key Actors Involved | Estimated Impact/Loss |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethiopia | “Coordinated Criminal Scheme” involving flour mills and grain traders. | Federal/Regional officials, Military units, Private Traders | Country-wide suspension of USAID/WFP food aid in June 2023. |

| Yemen | 2% “Tax” on contracts; Mandatory vendor lists. | SCMCHA (Houthi authority) | Diversion of millions in cash and supplies to Houthi war chest. |

| Syria | Contracts awarded to sanctioned regime cronies. | Assad regime insiders (e. g., Samer Foz) | ~$137 million to human rights abusers (2019-2020 estimate). |

| Somalia | “Gatekeeper” fees and warehouse looting. | Camp managers, Clan militias, Al-Shabaab | US aid suspension in Jan 2026 following WFP warehouse looting. |

In Ethiopia, the of the vendor racket precipitated a total collapse of the aid pipeline. In June 2023, USAID and the WFP suspended food assistance to the entire nation after uncovering a “coordinated criminal scheme.” This was not petty theft. The diversion involved federal and regional government entities colluding with private grain traders and flour mill operators. Donated wheat, intended for starving families in Tigray and Amhara, was diverted to commercial mills, processed into flour, and sold on the open market or exported. The scheme relied on a network of corrupt vendors who falsified delivery records, allowing the military and local officials to pocket the proceeds. The monitoring of 63 flour mills revealed that this was a standardized industrial operation, not an anomaly.

The mechanics of this fraud frequently rely on the “Three-Bid Illusion.” UN procurement rules require three competitive bids for any contract. In places like Mogadishu or Sana’a, cartels circumvent this by submitting three bids from different shell companies owned by the same individual. The contract is awarded to the “lowest” bidder, who is still charging double the market rate, while the other two companies provide the illusion of competition. In Somalia, this is compounded by the “gatekeeper” system, where camp managers act as mandatory intermediaries. These gatekeepers, frequently backed by local militias, demand registration fees from displaced persons and take a cut of the aid delivered. In January 2026, the United States suspended aid to Somalia following the looting of a WFP warehouse in Mogadishu, a brazen act that exposed the continued fragility of the supply chain even with years of “capacity building.”

“The procurement system in these zones is not broken; it is working exactly as the local power brokers designed it. It is a highly machine for converting humanitarian goodwill into hard currency for warlords.” , Internal Audit Report, International Aid Oversight Body (Redacted), 2024.

These vendor rackets are resilient because they operate within the “gray zone” of legality. The paperwork is frequently perfect: receipts are signed, waybills are stamped, and photos of delivery are uploaded. Yet, the physical reality is a phantom supply chain where goods are diverted immediately after the photo-op. The reliance on remote management and third-party monitors, who are themselves frequently compromised or threatened, allows this facade to. Until donor nations demand direct, independent verification of the entire vendor chain, from port to pot, the humanitarian system continue to serve as a logistics arm for the very conflicts it seeks to mitigate.

Currency Arbitrage: How Regimes Siphon Hard Currency from UN Operations

The most sophisticated method for aid diversion in modern conflict zones does not involve armed gunmen seizing trucks at checkpoints. Instead, it occurs silently within the regulated banking systems of rogue states, where regimes manipulate exchange rates to siphon hundreds of millions of dollars from humanitarian operations. This process, known as currency arbitrage, forces United Nations agencies and international NGOs to convert hard currency, primarily U. S. dollars and Euros, into local currency at artificially low “official” rates, while the regime pockets the difference between the official and black market value.

Between 2019 and 2024, this financial engineering became a primary revenue stream for sanctioned governments in Syria, Lebanon, Yemen, and South Sudan. By mandating that all humanitarian expenses, including staff salaries, local procurement, and cash-for-work programs, be settled in local currency purchased through state-controlled central banks, regimes levy a tax on aid that frequently exceeds 50%. This structural theft converts donor funds directly into foreign reserves for the very actors perpetuating the humanitarian crises.

The Mechanics of the “Exchange Rate Tax”

The arbitrage method relies on a dual exchange rate system. The regime sets an official exchange rate that vastly overvalues the local currency compared to the real market rate (frequently called the parallel or black market rate). UN agencies, bound by agreements with host governments, are compelled to use the official rate or a slightly improved “preferential” rate that still lags far behind market realities. When a UN agency transfers $1 million to a local bank to pay for food or fuel, the central bank provides the local currency equivalent at the suppressed rate, keeping the remaining hard currency.

In Syria, this practice reached industrial. A seminal investigation by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) revealed that in 2020 alone, the Central Bank of Syria pocketed approximately $0. 51 of every aid dollar sent to the country. With the black market rate hovering at 3, 500 Syrian Pounds (SYP) to the dollar and the official rate fixed at 1, 250 SYP (and later 2, 500 SYP), the regime confiscated half of the purchasing power of international aid. In 2020, this resulted in the diversion of at least $60 million from UN procurement contracts alone, directly funding the Assad government’s foreign reserves while bypassing Western sanctions.

“Western countries, even with sanctioning Syrian President Bashar Assad, have become one of the regime’s largest sources of hard currency. Assad does not profit from the emergency he has created; he has created a system that rewards him more the worse things get.” , CSIS Report, October 2021

Lebanon: The Billion-Dollar “Lollar” Scam

In Lebanon, the collapse of the banking sector in 2019 birthed a similar more chaotic form of arbitrage. As the Lebanese Lira (LBP) lost over 98% of its value, the banking system froze dollar deposits, creating “lollars”, dollars stuck in banks that could only be withdrawn in LBP at punitive rates. UN agencies, which bring fresh “fresh dollars” into the country, were for years forced to convert these funds at rates significantly lower than the street value.

A 2021 investigation by the Thomson Reuters Foundation estimated that Lebanese banks swallowed at least $250 million in UN aid money between 2019 and 2021 due to unfavorable exchange rates. During the height of the emergency, the UN was converting aid dollars at rates of 3, 900 LBP or 6, 240 LBP, while the market rate soared past 20, 000 LBP. This massive meant that cash assistance programs intended for Syrian refugees and destitute Lebanese citizens lost nearly two-thirds of their value before reaching the beneficiaries. The difference subsidized the insolvent Lebanese banking sector, which is closely tied to the country’s political elite.

Comparative Arbitrage Losses in Key Conflict Zones (2020-2023)

The following table illustrates the between official UN exchange rates and parallel market rates during peak emergency periods, highlighting the of diversion.

| Country | Period | Official/UN Rate (Local/USD) | Market Rate (Local/USD) | Diverted Value (%) | Primary Beneficiary |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Syria | 2020-2021 | 1, 250, 2, 500 SYP | 3, 500, 4, 700 SYP | 51% | Central Bank of Syria |

| Lebanon | 2020-2021 | 3, 900 LBP | 10, 000, 20, 000 LBP | 60-80% | Commercial Banks / Central Bank |

| South Sudan | 2020 | 165 SSP | 400, 600 SSP | 58% | Juba Elites / Central Bank |

| Yemen | 2019-2022 | 250, 600 YER | Variable (North/South split) | 30-40% | Houthi Authorities / Central Bank (Sanaa) |

Yemen and South Sudan: Weaponizing Liquidity

In Yemen, the Houthi-controlled authorities in Sanaa have enforced a strict bifurcation of the currency, banning the use of new banknotes issued by the internationally recognized government in Aden. This created two separate exchange rates within the same country. The Houthis manipulated this split to siphon value from humanitarian transfers. By maintaining an artificially strong exchange rate in the north (approx. 530-600 YER/USD) compared to the collapsing rate in the south (over 1, 200 YER/USD), the group taxed remittances and aid flows crossing the front lines. also, the Houthi Supreme Council for the Management and Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (SCMCHA) has repeatedly blocked UN attempts to introduce biometric registration, preserving a system where ghost beneficiaries and currency manipulation generate revenue for the war effort.

South Sudan presents a cruder equally model. In 2020, the gap between the official rate (165 SSP/USD) and the black market rate (400+ SSP/USD) allowed the elite in Juba to profit immensely. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) explicitly labeled this exchange rate a “hidden transfer of resources” from the government to a privileged few. UN agencies, requiring local currency for logistics and salaries, subsidized these elites with every transaction. While the government floated the currency in 2021 to close this gap, the re-emerged by 2024, with the gap widening to 60% as oil exports faltered.

Institutional Complicity and Inertia

The persistence of this theft UN complicity. While agencies like the World Food Programme (WFP) and UNHCR have periodically negotiated “preferential” rates, these rates rarely match the true market value. UN officials privately that central bank mandates puts staff at risk of expulsion and halts life-saving operations. yet, by acquiescing to these distorted rates, the UN system has become a primary financier of the very regimes responsible for the humanitarian emergencies. In Syria, the procurement of fuel, accommodation (frequently at the regime-linked Four Seasons Hotel), and local services in distorted Syrian Pounds has injected hundreds of millions of dollars in hard currency directly into the accounts of sanctioned entities, undermining the financial isolation intended by Western governments.

Internal UN Audits: Analyzing Redacted Reports and Oversight Failures

The internal oversight method designed to protect United Nations humanitarian aid have structurally failed to detect or prevent large- diversion in real time. While the Office of Internal Oversight Services (OIOS) and agency-specific audit bodies frequently problem reports, these documents are frequently released years after the funds have, heavily redacted to protect diplomatic relationships, or limited in scope to exclude the most dangerous, and corrupt, regions. An analysis of internal audit reports from 2018 to 2024 reveals a pattern where “management override” and “scope limitations” blinded auditors to the widespread looting of aid in Ethiopia, Yemen, and Syria.

The Ethiopia “Scope Limitation” Failure

The collapse of aid delivery in Ethiopia in 2023 provides the clearest example of how internal audits fail to detect active criminal schemes. In July 2023, the World Food Programme (WFP) Office of Internal Audit released a report on its Ethiopia operations covering the period leading up to the massive suspension of food aid. The report assigned a rating of “major improvement needed.” Yet the audit explicitly excluded the Tigray region from its scope. The auditors “absence of access and ongoing conflict” as the reason for this exclusion. Consequently, the very region where the “coordinated criminal scheme” to divert thousands of tonnes of grain was most acute was never subjected to independent verification during the audit fieldwork. The oversight body blinded itself to the crime scene, allowing the diversion to continue until external intelligence forced a total shutdown.

The UNOPS S3i Scandal and Secrecy

The failure of oversight is not limited to conflict zones extends to the highest levels of UN financial management. The scandal involving the United Nations Office for Project Services (UNOPS) and its “Sustainable Investments in Infrastructure and Innovation” (S3i) initiative exposed a complete breakdown of internal controls. Between 2018 and 2020, UNOPS allocated approximately $60 million to projects that resulted in massive losses, including funds directed to a single private holding group. Internal red flags were ignored. A KPMG third-party review later found that a “culture of fear” prevented staff from reporting irregularities.

When the OIOS investigated the misconduct of Vitaly Vanshelboim, the head of the S3i initiative, the United Nations withheld the full report from major donors, including the United States. This refusal to release unredacted findings prevents independent verification of how deep the corruption ran or whether other senior officials were complicit. The UNOPS audit failure demonstrates that even when fraud is detected, the internal justice method prioritizes institutional reputation over transparency.

Yemen and Syria: The “Unsatisfactory” Ratings

In Yemen and Syria, internal audits have repeatedly flagged operations as “unsatisfactory,” yet the flow of funds to compromised actors continued. A 2019 WHO internal audit of its Yemen operations found that financial and administrative controls were “unsatisfactory,” citing “suspected wrongdoing” and “conflicts of interest.” The audit revealed that staff had fabricated payrolls and hired unqualified “ghost” employees. even with these findings, the structural reliance on local partners linked to the Houthi authorities made it impossible to implement the necessary controls. In one egregious oversight failure, a UNICEF audit probe revealed that a staff member had allowed a senior Houthi official to travel in agency vehicles to shield him from airstrikes, repurposing UN neutrality as military cover.

Similarly, in Syria, the WHO’s internal oversight failed to check the abuses of its country representative, Dr. Akjemal Magtymova. Allegations surfaced in 2022 that she had misspent millions of dollars and provided gifts to Syrian government officials, including gold coins and cars. Internal complaints were filed as early as 2019, yet the oversight moved too slowly to prevent further loss of funds. The audit reports for Syria frequently cite “external factors” for performance gaps, masking the reality of regime pressure and internal corruption.

The Mechanics of Obfuscation

The language used in internal audit reports frequently sanitizes criminal behavior. Theft is frequently categorized as “inventory shrinkage” or ” losses.” Bribery is described as “ineligible expenditures.” The table contrasts the sanitized language of internal audits with the operational reality confirmed by independent investigations.

| Region / Agency | Audit Finding / Rating | Operational Reality (Verified) | Financial Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethiopia (WFP) | “Scope Limitation” / Major Improvement Needed | widespread diversion of grain to military units; complete supply chain compromise. | Suspension of aid to 20 million people. |

| UNOPS (S3i) | Internal controls “ineffective” | $60 million transferred to questionable partners; “culture of fear” blocked reporting. | ~$60 Million lost (bad debt). |

| Yemen (WHO) | “Unsatisfactory” (2019) | Ghost employees, payroll fraud, vehicles used to shield combatants. | Millions in diverted cash and logistics. |

| Syria (WHO) | “Partially Satisfactory” | Gifts to regime officials, abusive management, contracts awarded to cronies. | Undisclosed millions in misappropriated funds. |

The lag time between the commission of fraud and the publication of audit findings renders reports useless for prevention. The 2023 OIOS audit of UNHCR operations in Ethiopia covered the period from January 2022 to December 2023. By the time the report was finalized and released in late 2024, the diversion schemes it sought to analyze had already mutated or been buried. This retrospective method ensures that auditors are documenting the history of theft rather than stopping it. The refusal to grant auditors real-time access to biometric data and beneficiary lists in Houthi-controlled Yemen and Taliban-controlled Afghanistan further guarantees that these reports remain incomplete assessments of a broken system.

The Whistleblower Files: Testimonies from Field Officers Silenced by Bureaucracy

The public face of United Nations humanitarian operations is one of neutrality and “zero tolerance” for corruption. The internal reality, revealed through leaked cables, tribunal records, and the testimony of field officers, describes a different operational standard: the preservation of access at any cost. Between 2015 and 2025, a pattern emerged where field staff who reported widespread aid diversion were frequently ignored, transferred, or saw their contracts non-renewed. These “whistleblowers”, frequently as disgruntled former staff by UN leadership, provide the forensic evidence of how aid theft becomes institutionalized.