Why it matters:

- The legacy of corruption within the Vyapam board persists despite official rebranding efforts.

- The board's failure to maintain operational integrity has led to widespread fraud and compromised examinations.

The name Vyapam was once merely a Hindi acronym for the Madhya Pradesh Professional Examination Board or MPPEB. Today it serves as a global synonym for institutionalized corruption. While the state government officially rebranded the body as the Employees Selection Board or ESB in 2022 to wash away the stains of the past, the underlying infrastructure of Vyapam Legacy and fraud remains remarkably intact. Between 2020 and 2026 the board continued its controversial legacy, proving that a mere change in nomenclature cannot dismantle a deep rooted syndicate. The mandate of the board is theoretically simple and vital. It is entrusted with conducting entrance tests for admission into professional courses and managing recruitment exams for Class III and Class IV posts in the state government. For the youth of Madhya Pradesh, this institution holds the keys to social mobility and economic security. However, recent investigations reveal that this mandate has been subverted into a marketplace where merit is sold to the highest bidder.

The scale of operation handled by the board is massive. In the 2023 Patwari recruitment drive alone, nearly 10 lakh candidates applied for roughly 9000 posts. This desperation for government employment provides the perfect breeding ground for predatory touts and corrupt insiders. The primary function of the board is to conduct fair, transparent, and secure examinations. Yet, from 2020 to 2026, the board failed repeatedly at this fundamental task. The operational integrity of the MPPEB depends on secure software, unbiased examination centers, and secretive paper setting processes. Investigative findings from the last six years suggest that every single one of these pillars has been compromised.

The “Legacy” is not a ghost of the past but a living reality. In 2023 the Patwari recruitment examination became the new face of this old scandal.

The facade of reform crumbled publicly in July 2023 when the results of the Patwari recruitment exam were declared. The data showed a statistical impossibility that mirrored the brazenness of the original 2013 scandal. Seven out of the top 10 toppers appeared from a single examination center in Gwalior. This specific center, the NRI College of Engineering, was allegedly owned by a serving MLA. Further scrutiny revealed that these toppers, who achieved near perfect scores, could not answer basic questions about the subjects they had ostensibly mastered. One topper was unable to even name the eight subjects included in the syllabus. This was not an isolated glitch but a coordinated subversion of the mandate.

The rot extends beyond job recruitment into the medical and nursing education sectors. While MBBS admissions moved to the centralized NEET system, the state board and allied bodies retained control over nursing and paramedical accreditation, creating a new avenue for fraud. The 2024 nursing college scam exposed how the board and the state nursing council allowed “ghost colleges” to operate. These were institutions that existed only on paper, lacking buildings, faculty, or students, yet they were granted “suitable” status to issue degrees. The corruption was so pervasive that even the cleanup crew was compromised. In May 2024 the CBI caught its own officers accepting bribes worth lakhs from these nursing colleges to issue favorable inspection reports. The protectors of the mandate had become partners in the crime.

Earlier in 2021 the Agriculture Extension Officer exam offered another glimpse into this rigged system. The top 10 candidates scored identical marks and committed the exact same errors, a signature of the “solver gang” method where answer keys are circulated beforehand. The government was forced to cancel the exams after the media exposed these anomalies, yet the structural flaws within the MPPEB allowed the same patterns to repeat in 2022 during the Primary School Teacher Eligibility Test. Screenshots of the question paper went viral on social media while the exam was still in progress, allegedly leaked from a computer linked to a powerful political aide.

The mandate of the MPPEB is to select the best talent to serve the state. Instead, from 2020 to 2026, it acted as a gatekeeper that excluded the deserving poor in favor of the wealthy incompetent. The rebrand to MPESB has done nothing to alter the operational DNA of Vyapam. As long as examination centers can be bought and software vendors manipulated, the legacy of Vyapam will continue to haunt the future of Madhya Pradesh.

Early Warning Signs: Complaints and Irregularities Prior to 2013

The monumental collapse of integrity within the Madhya Pradesh Professional Examination Board, commonly known as Vyapam, did not occur in a vacuum. Long before the explosive revelations of 2013, the state witnessed a steady accumulation of red flags, ignored complaints, and systemic irregularities that signaled the rotting core of its recruitment machinery. An investigative retrospective, empowered by judicial verdicts and forensic data released between 2020 and 2026, reveals that the “Vyapam scam” was not a singular event but a thriving industry operating with impunity for over a decade.

The earliest tremors were felt as far back as the late 1990s, with the first First Information Report (FIR) regarding fraudulent admissions filed in 2000. However, the period between 2004 and 2012 represents the critical era of missed opportunities. During these years, whistleblowers and local activists inundated state offices with specific allegations of impersonation in the Pre Medical Test (PMT). Retrospective data analysis from the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), detailed in court submissions throughout 2021 to 2024, confirms that these early complaints were accurate. For instance, the complaints regarding the 2012 Police Constable Recruitment Examination, initially dismissed by local authorities, were validated over a decade later. In December 2025, a special CBI court in Gwalior finally convicted two individuals for impersonation in that specific 2012 exam, sentencing them to seven years of rigorous imprisonment. This 2025 verdict serves as irrefutable proof that the warning signs of 2012 were grounded in reality, not conspiracy.

The modus operandi identified in these early years was strikingly consistent with the “Legacy” scams seen in the 2020 to 2026 period. In 2009, complaints surfaced regarding the “engine bogie” system, where wealthy candidates were seated strategically behind paid solvers. Authorities established a committee in 2009 to investigate PMT irregularities, which released a report in 2011 confirming suspicious patterns. Yet, no structural overhaul occurred. The cost of this inaction is quantifiable in modern terms. Just as the 2009 warnings were disregarded, similar irregularities appeared in the 2023 Patwari recruitment exam. In July 2023, data revealed that seven out of ten toppers in the Patwari exam hailed from a single center in Gwalior, a statistical anomaly that mirrors the clustered success rates flagged in the 2011 report. The failure to dismantle the infrastructure of fraud prior to 2013 allowed the same syndicate networks to evolve, leading to what critics called “Vyapam 2.0” in 2023.

Furthermore, the legacy of silencing early whistleblowers continues to haunt the legal landscape. Dr. Anand Rai, who played a pivotal role in exposing the pre 2013 rot, faced continued legal battles well into the current decade. His arrest in 2022 and subsequent dismissal from government service in 2023 highlight a persistent hostility toward those who document these early warning signs. The state apparatus, rather than learning from the 2000 to 2012 era, appears to have refined its defense mechanisms against exposure.

The scope of the pre 2013 rot is further illuminated by the sheer volume of cases that clogged the judicial system well into the 2020s. By January 2020, the CBI had secured 94 convictions related to these early exams. By 2024, the agency was still filing charge sheets for cases dating back to the 2012 PMT, underscoring the depth of the backlog. In a grim parallel, the Nursing College Scam of 2024 exposed that the regulatory negligence observed in 2009 has metastasized. A CBI probe ordered by the High Court in 2024 investigated 308 nursing colleges, revealing that many lacked basic infrastructure, a fraudulent practice that mirrors the “ghost schools” and fake domicile certificates reported but ignored in 2010.

In conclusion, the period prior to 2013 was not merely a prelude but a fully functional era of corruption that was normalized by administrative apathy. The convictions delivered between 2020 and 2026 for crimes committed in 2012 stand as a judicial testament to that era. They prove that the mechanisms for buying jobs and medical seats were robust, visible, and reported long before the scandal officially “broke.” The Vyapam legacy is thus defined not just by the scam itself, but by the decade of deliberate blindness that allowed it to flourish, a pattern of governance that recent data suggests has yet to be fully eradicated.

The Whistleblowers: Profiles of Dr. Anand Rai, Ashish Chaturvedi, and Others

The shadow of the Vyapam scam does not fade; it merely lengthens. For the men who exposed the rot within the Madhya Pradesh Professional Examination Board over a decade ago, the period from 2020 to 2026 has not brought vindication but a fresh cycle of persecution. The machinery they sought to dismantle has mutated, spawning new scandals like the Nursing College fraud and the Patwari recruitment irregularities, while the whistleblowers themselves remain under siege.

Dr. Anand Rai: The Price of Persistence

Dr. Anand Rai, an ophthalmologist and the primary whistleblower who blew the lid off the initial scam, found himself the target of the state apparatus once again in the current decade. In 2022, Dr. Rai exposed what is now known as the MP TET leak, alleging that the Teacher Eligibility Test paper had been leaked to favor specific candidates. He shared screenshots implicating an Officer on Special Duty to the Chief Minister.

The backlash was swift and severe. In April 2022, the Madhya Pradesh Crime Branch arrested Dr. Rai from a hotel in Delhi. He was not treated as a witness but as a criminal conspirator. Following his arrest, the state government suspended him from his post as a Medical Officer. The persecution intensified in March 2023 when he was dismissed from government service entirely, stripping him of his livelihood. Although the Supreme Court granted him bail in January 2023 regarding a separate case under the Atrocities Act, Dr. Rai spends his days fighting legal battles rather than patients.

Ashish Chaturvedi: A Life Under Siege

Ashish Chaturvedi, known as the whistleblower on the bicycle, continues to live a life defined by paranoia and very real physical danger. Despite providing evidence that implicated powerful politicians and their relatives, Chaturvedi remains vulnerable. The years between 2020 and 2026 saw an escalation in the threats against him.

In a harrowing incident in March 2025, police personnel allegedly entered his residence in Gwalior and assaulted him. Chaturvedi reported that he was beaten, humiliated, and forcibly injected with an unknown substance at a trauma center. This assault was followed by the registration of an FIR against him, a common tactic used to silence dissenters by burying them in litigation. In May 2025, the Madhya Pradesh High Court had to intervene, issuing notices to the Director General of Police regarding this malicious prosecution. For Chaturvedi, the fight is no longer just about exposing corruption but about basic physical survival.

Ravi Parmar and the New Wave

As the legacy of Vyapam evolved, so did the roster of those fighting it. Ravi Parmar emerged as a key voice exposing the massive Nursing College Scam that rocked the state in 2024. Parmar revealed that hundreds of nursing colleges existed only on paper, operating without faculty or infrastructure while handing out degrees. His activism led to a High Court ordered CBI probe.

However, the system struck back with irony. In May 2024, the CBI arrested two of its own inspectors for accepting bribes to give “clean chits” to the very nursing colleges they were investigating. Parmar stood vindicated yet horrified as the guardians of the law were caught partaking in the loot. By October 2025, Parmar was again at the forefront, exposing how private colleges used government employees as “ghost faculty” to bypass regulations.

The Unending Cycle

The timeline from 2020 to 2026 proves that the Vyapam scam was not an event but a culture. The Patwari recruitment exam of 2023 followed the same playbook: toppers emerging from a single center owned by a political figure, identical errors in answer sheets, and a subsequent whitewash. For Dr. Rai, Ashish Chaturvedi, and Ravi Parmar, the legacy of Vyapam is a daily reality of court dates, suspended careers, and the constant, chilling knowledge that in Madhya Pradesh, the truth is the most dangerous thing one can possess.

The Vyapam Legacy: The Munnabhai Method Lives On

The ghost of Vyapam does not rest. It merely changes hosts. In the early 2010s, the Madhya Pradesh Professional Examination Board scam exposed a rot so deep it stained the very idea of merit in India. More than a decade later, as we review the years from 2020 to 2026, the legacy of purchasing public service jobs and medical seats remains intact. The methods have evolved, but the core mechanism remains the same: The Impersonator.

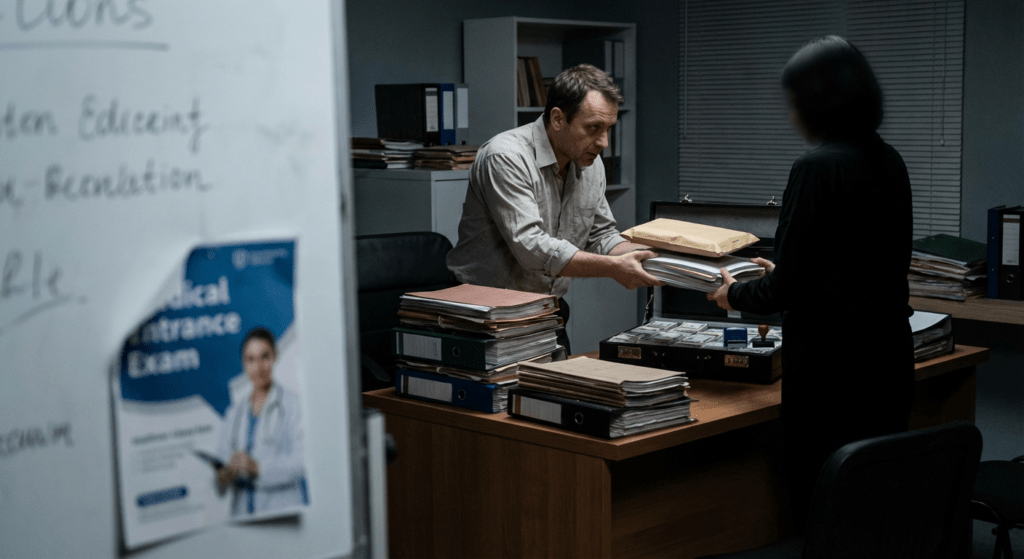

This is Modus Operandi I: The Munnabhai Method.

The operational logic is simple. A brilliant scholar, often a medical or engineering student desperate for quick cash, is hired to sit the exam for a wealthy, underqualified client. By 2026, this has become a highly organized corporate service across the Hindi belt, specifically Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, and Rajasthan.

The Solver Gangs of 2024

The year 2024 marked a turning point in the scale of these operations. During the Uttar Pradesh Police Constable recruitment drive, the state police unearthed a network that functioned with industrial precision. In February 2024 alone, over 122 individuals were arrested across districts like Etah, Mau, and Prayagraj. These were not isolated cheaters but employees of a syndicate.

The Rate Card (2024 Estimates):

Constable Post: Rs 3 Lakh to Rs 5 Lakh

NEET UG Seat: Rs 20 Lakh to Rs 35 Lakh

State Teacher (REET): Rs 10 Lakh to Rs 15 Lakh

The “solvers” were often recruited from coaching hubs in Patna and Allahabad. Constable Niranjan, arrested in the 2024 crackdown, had sat for at least four candidates before his capture. The gang used advanced photo mixing software to blend the facial features of the solver and the candidate on the admit card, fooling tired invigilators who relied on a quick glance.

Vyapam Legacy

Vyapam Fraud Rate Card

Vyapam 2.0: The MP Patwari Scam

Madhya Pradesh saw the spectre return with the MP Patwari Exam of 2023. This case, now infamously known as “Vyapam 2.0,” displayed the audacity of the impersonation model. When results were declared, seven out of the top ten rankers came from a single center: NRI College of Engineering in Gwalior.

Investigations revealed that these toppers, who scored full marks in subjects like English, struggled to sign their names in Hindi on live television. They were not ghosts; they were proxies. The investigation dragging into 2025 revealed that the digital logs were manipulated, but physical impersonation played a key role. Biometric bypasses were sold as premium add ons. A thumbprint cast in silicon, worn by a solver, could fool the scanners used at rural centers.

The Rajasthan Connection

By 2025, the focus shifted to Rajasthan. The Special Operations Group (SOG) cracked open the REET (Rajasthan Eligibility Examination for Teachers) files from 2021 and 2022. In a massive sweep concluding in mid 2025, the SOG booked 123 teachers who were already serving in government schools.

The interrogation of Ummed Singh, a government school teacher arrested in April 2025, provided a chilling look into the life of a professional impersonator. Singh was not just a solver; he was a machine. He confessed to appearing as a proxy in seven different major recruitment exams between 2018 and 2024. He wrote exams for Sub Inspectors, Hindi Lecturers, and Physical Education teachers. He was the “Munnabhai” who never got caught, until facial recognition software finally flagged his recurring image across mismatched profiles.

The Future of Fraud

As we stand in 2026, the data shows that biometric locks and Aadhaar verification have not stopped the impersonators. They have only raised the price. The “Munnabhai” method survives because it relies on the one variable technology cannot fully patch: human corruption. From the “Solver Gangs” of UP to the “Proxy Toppers” of MP, the Vyapam legacy endures, selling the dreams of the poor to the highest bidder.

Modus Operandi II: The Engine Bogie System (Strategic Seating Arrangements)

The term Vyapam may have originated in Madhya Pradesh a decade ago, but its ghost continues to haunt the Indian recruitment landscape between 2020 and 2026. While the original scandal exposed the systematic manipulation of entrance exams, the specific technique known as the Engine Bogie system has not disappeared. It has merely evolved. In this arrangement, a brilliant student or professional solver (the Engine) is strategically seated directly in front of or beside a paying candidate (the Bogie). The Engine completes their paper efficiently and facilitates copying for the Bogie. In the digital age of 2020 to 2026, this analog fraud has transformed into a sophisticated operation involving venue compromise and algorithmic manipulation.

The 2023 MP Patwari Resurrection

The most glaring evidence that the Engine Bogie legacy survives appeared during the Madhya Pradesh Patwari recruitment exam in 2023. The Madhya Pradesh Employees Selection Board (ESB), the successor agency to the infamous Vyapam, conducted an examination to fill over 9,000 vacancies. When results were declared, a statistical anomaly alerted investigators. Seven out of the top ten rankers came from a single examination center: the NRI College of Engineering and Management in Gwalior.

This clustering effect is the hallmark of a modern Engine Bogie setup. Unlike the random allocation of roll numbers promised by computerized systems, these candidates seemingly managed to bypass randomization. Investigations revealed that many of these toppers had signed their forms in Hindi yet scored full marks in English sections. The center acted as the ultimate Engine, creating a safe zone where solvers could assist multiple Bogies simultaneously. The venue itself became the facilitator, ensuring that paying candidates were seated in blind spots of CCTV coverage or in proximity to facilitators.

NEET UG 2024 and the Cluster Phenomenon

The legacy of strategic seating exploded onto the national stage again with the NEET UG 2024 controversy. While much of the debate focused on paper leaks, the underlying mechanics in specific centers mirrored the Vyapam playbook. In Haryana, a single center in Jhajjar produced a staggering cluster of toppers. Six students from this specific venue achieved a perfect score of 720/720. Two others scored 718 and 719.

This statistical impossibility points to a systemic breach reminiscent of the Engine Bogie method. In this iteration, the Engine was not necessarily a fellow student but the invigilation system itself. Candidates allegedly chose specific centers far from their home towns (such as students from Odisha or Bihar choosing Godhra in Gujarat), paying upwards of 10 lakh rupees. In the Godhra case investigated by the CBI in 2024, the modus operandi shifted slightly. The Bogies were instructed to leave answers blank. The Engine (comprised of compromised teachers and invigilators) would fill in the correct answers on the OMR sheets after the exam concluded. This is the ultimate evolution of the system: the Engine no longer needs to sit in the hall; they operate in the shadows during the processing phase.

The Digital Engine: Remote Access Scams

Between 2020 and 2025, the Engine Bogie system also migrated to online server rooms. In various state level engineering and subordinate service exams, the physical solver was replaced by remote access software. In the Jammu and Kashmir Sub Inspector recruitment scam (2022), investigators found that terminal access was compromised. The candidate (Bogie) sat in front of the computer screen, pretending to work, while the Engine (a solver located in a different city) controlled the mouse and keyboard via remote desktop applications. This digital impersonation requires the collusion of venue owners who disable local firewalls to allow external connections.

The persistence of these methods proves that the infrastructure of fraud established during the original Vyapam era remains intact. The Engine Bogie system has survived by adapting to new technologies and exploiting the desperation of millions. Whether through physical proximity in Gwalior or OMR manipulation in Godhra, the objective remains the same: ensuring the Bogie arrives at the destination of a government job, regardless of their lack of merit.

Modus Operandi III: OMR Sheet Manipulation and Blank Answer Scripts

The evolution of examination fraud in India has moved beyond the crude “solver gangs” of the early 2000s. While impersonation was the hallmark of the original Vyapam scandal in Madhya Pradesh, the period from 2020 to 2026 has witnessed the rise of a far more insidious technique. This new method requires no brilliant proxy scholars and no risky electronic devices in the exam hall. It relies on the ultimate breach of trust: the corruption of the “Strong Room” itself. This is Modus Operandi III, where the Optical Mark Recognition or OMR sheet is weaponized through its very emptiness.

The Blank Script Protocol

The premise of this scam is audaciously simple. Candidates who have paid the bribe are instructed to leave their OMR answer sheets largely blank. They might attempt a safe number of questions, perhaps 30 or 40 out of 100, to avoid suspicion during invigilation, but the critical winning circles are left untouched. The real work begins after the exam concludes, when the answer scripts are in transit or stored in the secure custody of the recruitment board.

Between 2021 and 2022, the Karnataka Police Sub Inspector (PSI) recruitment scam provided the definitive blueprint for this operation. The investigation revealed that candidates paid between 30 lakh rupees and 85 lakh rupees to secure a position. The scam did not happen in the exam hall but in the recruitment wing headquarters. High ranking officials, including an Additional Director General of Police, were implicated in facilitating access to the secure strong room where the OMR sheets were kept. Corrupt insiders then filled in the correct answers on the blank sheets, ensuring the candidates made the merit list with mathematically impossible precision.

Case Study: The Haryana Dental Surgeon Heist

In November 2021, a similar pattern emerged in Haryana during the recruitment for Dental Surgeons and Civil Services officers. The Haryana Public Service Commission (HPSC) found itself at the center of a storm when its Deputy Secretary, Anil Nagar, was arrested. The vigilance bureau recovered millions in cash, but the digital evidence was more damning.

The modus operandi here was surgical. The bribe payers were told to attempt only what they knew and leave the rest blank. These sheets were then segregated at the scanning center. The conspirators used the secrecy of the scanning room to physically fill in the blank bubbles before the digital image was captured. The forensic analysis later showed that the ink used to fill the “winning” bubbles differed from the ink used by the candidate in the exam hall. The rates for these seats ranged from 20 lakh to 35 lakh rupees, a premium price for a guaranteed government job.

The Spread of the Virus: 2023 to 2026

Despite these high profile arrests, the method persisted because it eliminated the risk of getting caught with a Bluetooth device. In 2023, the Madhya Pradesh Patwari exam faced intense scrutiny. While the board had shifted to online modes, the legacy of Vyapam haunted the results when seven out of ten toppers emerged from a single center in Gwalior, sparking allegations of screen sharing and remote access, the digital equivalent of the blank OMR scam.

By 2024, the rot had reached the Arunachal Pradesh Public Service Commission (APPSC). The repercussions of the Assistant Engineer exam leak, which involved the manipulation of award sheets and OMR data, led to massive civil unrest and a “Black Day” observance in February 2025. The investigation revealed a decade long racket where the sanctity of the answer script meant nothing.

The data from 2020 to 2026 suggests a disturbing trend. As surveillance in exam centers improves with jammers and frisking, the corruption migrates upwards to the custodians of the data. The blank OMR sheet is no longer a sign of a student giving up; it is now a secret code, a signal to the corrupt insider that the payment has been made, and the seat has been bought.

“The candidate does not need to know the answer. They only need to know the person who holds the keys to the strong room.”

This systemic failure erodes the very foundation of meritocracy. When the lock on the strong room is broken from the inside, the examination becomes nothing more than an auction, selling the dreams of millions to the highest bidder.

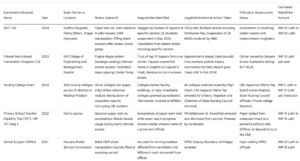

The Rate Card: The Black Market Pricing of Medical Seats and Government Jobs

By February 2026, the illicit trade in public examination papers has evolved from a clandestine operation into a robust parallel economy. While the Vyapam scandal of the past decade exposed the machinery of rigged entrance exams, the years stretching from 2020 to 2026 have codified a specific pricing structure for corruption. This section investigates the “Rate Card,” a grim menu of services where merit is auctioned to the highest bidder.

Agents and brokers operating across Bihar, Rajasthan, Haryana, and Uttar Pradesh have standardized these rates based on the desirability of the post, the risk factor, and the expected lifetime earnings of the job. The market dynamics are ruthless. Inflation affects bribes just as it affects milk or gasoline.

The Official Black Market Rate Card (2020 to 2026)

Data aggregated from police charge sheets, ED reports, and confessions in Bihar, Rajasthan, Haryana, and UP.

- NEET UG (MBBS Seat Access)

Service: Paper leak via “cram sessions” or digital distribution.

Price: ₹30 Lakh to ₹50 Lakh

Context: The 2024 Patna module established this baseline. Agents charged candidates up to ₹50 Lakh for memorizing answers in safe houses 24 hours prior to the exam.

- Dental Surgeon (HPSC Class I)

Service: Blank OMR sheet manipulation.

Price: ₹25 Lakh to ₹35 Lakh

Context: The Haryana Public Service Commission scam revealed that candidates left answer sheets blank, which were later filled by officials for a premium fee.

- Senior Teacher (RPSC)

Service: Advance paper access.

Price: ₹5 Lakh to ₹8 Lakh (Retail)

Context: While brokers paid ₹60 Lakh to source the master copy from corrupt officials, they sold access to individual candidates at a retail markup, creating a pyramid of profit.

- Police Constable (UP & State Boards)

Service: Leaked paper or solver gang services.

Price: ₹7 Lakh to ₹8 Lakh

Context: For the 2024 UP Police Constable exam, brokers demanded ₹7 Lakh to provide answer keys hours before the test commenced.

- State Civil Services (Prelims)

Service: OMR tampering and interview fixing.

Price: ₹15 Lakh to ₹20 Lakh

Context: This rate specifically covered the preliminary stage clearance in states like Haryana, with additional payments required for the main exam and interview rounds.

The Economics of Desperation

The pricing strategy reflects a cold economic calculation. An MBBS seat is the most expensive asset because the potential return on investment for a doctor is perceived as infinite in the long run. The 2024 NEET scandal highlighted this disparity. Brokers in Patna demanded ₹30 Lakh as a minimum entry price. This sum effectively excluded the poor, ensuring that corruption remained a privilege of the wealthy.

For government jobs, the calculation differs. A Police Constable position, priced at ₹7 Lakh, appeals to rural families who may sell land or take high interest loans to pay the bribe. They view the job as a guarantee of lifetime security and social status. The bribe is not seen as a crime but as a capital investment.

Evolution of the Mechanism

Between 2020 and 2026, the mechanism of delivery shifted. The era of physical paper theft gave way to digital leaks and “dummy candidates.” In January 2026, Rajasthan police arrested a candidate who had employed a dummy writer back in 2022, revealing that the service included a “full package” where the actual applicant never even entered the exam hall. This premium service commanded rates significantly higher than simple paper leaks, often exceeding ₹20 Lakh for Grade II jobs.

The persistence of these rates into 2026 demonstrates a failure of deterrence. Despite the cancellation of the 2016 West Bengal school panels by the Supreme Court and mass arrests in the UP Police leak case, the market adapts. When surveillance increases, the price rises to cover the risk premium. The “Rate Card” is not merely a list of numbers; it is an indictment of a system where integrity is the only currency that holds no value.

The following is a long-form investigative section regarding the network of middlemen in recent state board and medical entrance scams.

The Middlemen Network: How Coaching Centers and Brokers Recruited Candidates

The ghost of the Vyapam scam has not vanished from Madhya Pradesh; it has merely evolved. Between 2020 and 2026, a sophisticated web of brokers, coaching centers, and private college owners replaced the crude bribery of the past with a distributed “franchise model” of corruption. While the original scandal focused on a compromised examination board, the new era, often whispered about as Vyapam 2.0, operates through decentralized recruitment hubs that identify, groom, and facilitate paying candidates long before they enter the exam hall.

The Front Office: Coaching Centers as Recruitment Hubs

The most significant shift in the last five years is the weaponization of legitimate coaching centers. These institutes serve as the perfect front office for illicit deals. They screen students not for their academic potential, but for their financial capacity. Investigations into the 2024 NEET controversies revealed how deep this rot runs, extending its tentacles from Gujarat to the heart of Madhya Pradesh.

In Godhra, the Roy Overseas coaching center owner Parshuram Roy was arrested in May 2024. Investigators found blank cheques and postdated cheques from parents in his possession. The modus operandi was simple yet effective: parents deposited cheques as security. If the candidate secured a seat through the “setting,” the cash was transferred, and the cheque returned. If the plan failed, the cheque was voided. This financial safety net emboldened middle class families to participate in the fraud, knowing they would only pay for results.

The Gwalior Connection: The Patwari Exam Anomaly

Nowhere was this brazen coordination more visible than in the Madhya Pradesh Patwari recruitment exam of 2023. The results declared in July 2023 sparked immediate outrage. A single examination center, the NRI College of Engineering in Gwalior, produced 7 out of the top 10 toppers in the state. This statistical impossibility alerted activists and opposition leaders to a potential rig.

The college, owned by Sanjeev Kumar Kushwaha, a local MLA, became the epicenter of the scandal. Investigative scrutiny revealed that toppers from this center, including the infamous Pooja Rawat, could not answer basic questions about the state or their subjects during media interviews. Yet, they had scored nearly perfect marks. The network here did not just leak a paper; it likely utilized a remote access compromise or a “solver gang” where experts filled out answers for candidates. The fact that candidates signed their forms in Hindi but scored full marks in English provided a smoking gun for investigators, suggesting the person taking the test was not the person who signed the application.

“The system has moved from retail corruption to wholesale contracts. In 2023, the rate for a Patwari seat was reportedly fixed at 15 lakh rupees, collected by brokers who guaranteed a specific exam center.” — Source close to the MP Special Task Force.

The Nursing College Cartel: Directors as Middlemen

By 2024, the corruption had infected professional education governance itself. The CBI investigation into the Madhya Pradesh Nursing College scam unmasked a new layer of middlemen: the college directors themselves. In May 2024, the CBI arrested 13 people, including two of its own inspectors, Rahul Raj and Sushil Kumar Majoka.

The middlemen in this case were not street level touts but prominent figures like Jugal Kishore and Om Goswami. These men allegedly ran a “bribe collection module.” They collected money from nursing colleges that lacked infrastructure—ghost colleges with no faculty or buildings—and funneled it to the inspection teams. The going rate to certify an unfit college was between 2 lakh and 10 lakh rupees per institution. This network ensured that thousands of unqualified nursing students received degrees, flooding the healthcare system with incompetent staff.

Logistics of the Leak

The operational logistics of these networks between 2020 and 2025 relied on “safe houses.” In the broader context of the NEET 2024 leaks which had strong links to the “solver gangs” operating in Bihar and MP, police discovered locations like the “Learn Boys Hostel” in Patna. Here, candidates were brought 24 hours before the exam to memorize answers from leaked papers. The brokers handled everything: transport, accommodation, and the destruction of evidence.

This timeline from 2020 to 2026 proves that the Vyapam legacy is intact. The middlemen have simply professionalized. They use coaching centers to scout clients, private colleges to host rigged exams, and encrypted apps to manage payments. Until these recruitment hubs are dismantled, the sale of jobs and seats will remain a thriving industry.

The Political Nexus: Allegations Against Ministers and High Profile Officials

The shadow of Vyapam, a scandal that once defined corruption in the Indian heartland, has not faded. Instead, between 2020 and 2026, it evolved into a more sophisticated beast. While the original scam involved impersonators and rigged answer sheets, the modern iteration exposes a deeper rot: a brazen political nexus where the line between the regulator and the racketeer has vanished. This section investigates the allegations against ministers and high ranking officials who have allegedly turned state recruitment boards into personal fiefdoms.

The Patwari Recruitment Scandal: A Political Power Play

The most glaring evidence of political complicity emerged during the Madhya Pradesh Patwari recruitment exam in 2023. The results declared in July of that year revealed a statistical anomaly that defied logic. Seven out of the top ten rankers hailed from a single examination center: the NRI College of Engineering in Gwalior.

The college was not merely a random venue. It was owned by Sanjeev Kushwaha, a sitting Member of Legislative Assembly (MLA) from the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). The allegations were damning. Candidates who scored full marks in English signed their names in Hindi, suggesting they lacked basic proficiency in the subject they supposedly aced. Despite the outcry, the political machinery moved swiftly to insulate its own. While protests erupted across Bhopal and Indore, the initial response from the state was denial.

In February 2024, a one member judicial inquiry commission submitted a report that the opposition termed a “clean chit.” The report found no organized mafia involvement, a conclusion that stood in stark contrast to the ground reality of identical errors made by toppers and the specific geographic concentration of successful candidates. The nexus here was not just about money; it was about political patronage protecting the corrupt infrastructure used to harvest bribes.

The Nursing College Scam: When the Watchdog Bites

If the Patwari scam highlighted political ownership of the fraud, the Nursing College scam of 2024 exposed the corruption of the investigators themselves. The Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), tasked with cleaning up the system, found its own officers on the payroll of the scamsters.

In May 2024, the CBI arrested its own inspector, Rahul Raj, for accepting bribes to issue favorable inspection reports to nursing colleges that existed only on paper. These “ghost colleges” lacked faculty, infrastructure, and students, yet they received accreditation to grant medical degrees. The bribes ranged from 200,000 to one million rupees per institute.

The nexus reached higher than rogue investigators. In December 2024, the Madhya Pradesh High Court ordered the removal of the Registrar and Chairman of the State Nursing Council. The court observed that these high ranking officials were likely involved in the initial recognition of fraudulent colleges. This was a direct indictment of the state bureaucracy, suggesting that the bribe money collected by middlemen flowed upwards to the very officials appointed to safeguard public health standards.

A Minister Confesses: The 2025 Anganwadi Revelation

Perhaps the most surreal moment in this ongoing saga occurred in July 2025. Nagar Singh Chauhan, a cabinet minister, released a video statement admitting that brokers were demanding bribes for Anganwadi positions within his own department. He hinted that departmental officers were complicit in the racket.

This was a rare instance of the “Vyapam Legacy” being acknowledged from within the cabinet. However, political analysts viewed this not as a crusade against corruption, but as a symptom of internal factionalism. The admission confirmed what aspirants had known for years: the rate card for government jobs was fixed, and the brokers operated with the tacit approval of the administrative machinery.

The Judicial Verdicts: Justice Delayed and Denied

While fresh scams brewed, the legal system struggled to close old wounds. In December 2025, a special court finally convicted two impersonators for a 2012 crime, sentencing them to seven years. Yet, the big fish remained elusive. In May 2025, a police constable named Sajan Singh Thakur became the first candidate to be acquitted in a Vyapam case due to a lack of evidence.

The pattern from 2020 to 2026 is clear. The “Political Nexus” has successfully shifted the risk to the lower rungs—the impersonators, the students, and the low level clerks. Meanwhile, the owners of the colleges, the political patrons who shield them, and the high ranking officers who sign the files remain largely untouched. The legacy of Vyapam is no longer just about buying a seat; it is about buying immunity from the law.

Bureaucratic Complicity: The Role of MPPEB Insiders and System Administrators

The ghost of Vyapam never really left Madhya Pradesh; it merely upgraded its software. Between 2020 and 2026, the scandals rocking the renamed Madhya Pradesh Employees Selection Board (MPESB) reveal a disturbing evolution in bureaucratic complicity. The primitive days of physical impersonation, where a hired scholar sat in for a candidate, are largely over. In their place sits a far more insidious mechanism: the digital hijacking of examination nodes facilitated by center operators and board insiders.The rebranding of the board from MPPEB to MPESB was meant to signal a fresh start. Yet, the systemic rot remains embedded in the administrative architecture. The 2023 Patwari recruitment examination stands as the most glaring testament to this enduring legacy. When the results were declared, seven out of ten toppers hailed from a single center: NRI College of Engineering in Gwalior. This facility was not a random venue but an institution owned by a sitting legislator. The statistical improbability of such a result flagged immediate suspicion, but the methodology pointed directly to insider collusion.

Investigations revealed that the complicity had shifted from the exam hall floor to the server room. System administrators, often employees of the private vendors hired by the board, effectively sold administrative access. In the Patwari case, candidates who signed their forms in Hindi somehow scored perfect marks in English. This was not a miracle of learning but a result of remote screen access. Insiders disabled the local firewalls, allowing solvers sitting in remote locations to view the screen of the candidate and select the correct answers. The candidate merely sat at the terminal, moving the mouse to simulate activity.

This level of access requires approval from the highest levels of the exam conducting body. A mere center manager cannot bypass the encryption protocols mandated by the tender without the tacit oversight of board officials. The 2021 Agriculture Extension Officer scam provided a precursor to this. Ten toppers scored identical marks with identical errors, a statistical impossibility in a fair test. The investigation exposed that the contract for conducting the exam was handed to NSEIT, a firm that had faced blacklisting in other states. Board bureaucrats ignored these red flags, prioritizing vendor continuity over integrity.

The complicity extends beyond recruitment exams into the regulation of medical education, keeping the spirit of the original PMT scam alive. The Nursing College scam, which unraveled between 2022 and 2024, exposed how the bureaucracy monetized accreditation. The CBI probe into 308 nursing colleges found that many existed only on paper, lacking buildings, faculty, or clinical facilities. Yet, they received full recognition from the state nursing council year after year.

In May 2024, the depth of this collusion was laid bare when CBI Inspector Rahul Raj was arrested for accepting bribes to issue clean chits to these deficient colleges. The protectors had become the predators. The High Court eventually ordered a reinspection of 169 colleges that had previously been cleared, acknowledging that the regulators themselves were compromised.

The role of the “System Administrator” has thus expanded. It is no longer just the IT guy at the computer lab. It now includes the registrar who overlooks fake faculty lists, the inspector who signs off on phantom buildings, and the board official who drafts the tender to favor specific compromised vendors.

By 2025, the modus operandi had fully matured into a “service delivery model” where cash exchanged hands not for a promise of selection, but for a guarantee of system access. The leaked screenshot from the 2022 TET Varg 3 exam, showing the question paper on a mobile device outside the hall while the exam was active, carried the name of a prominent official on the screen overlay. This was not a breach; it was a service.

The legacy of Vyapam in this decade is the seamless integration of corruption into the digital workflow. The MPESB insiders do not need to smuggle papers out anymore; they simply open the digital back door and invite the highest bidder in.

The Digital Evidence: Analyzing the Recovered Excel Sheets and Hard Drives

The legacy of Vyapam is not merely a tale of bribed officials or proxy candidates. It is, at its core, a story of digital manipulation. When investigators seized the computer of the chief system analyst Nitin Mohindra in July 2013, they found more than just files. They found a systemic template for corruption stored in Excel sheets. In the years between 2020 and 2026, this digital modus operandi has not vanished. It has evolved. The “Excel sheet” has become a metaphor for a persistent shadow economy in state board examinations, from the Madhya Pradesh Patwari recruitment to the Nursing College recognition scandal.

The Original Template: Nitin Mohindra’s Hard Drive

To understand the current forensic landscape, one must analyze the “ur text” of the scandal. The original hard drive contained Excel files where candidates were listed alongside their “sponsors.” These sponsors included ministers, bureaucrats, and middlemen. The forensic controversy that persists today revolves around the “altered” versus “original” files. Whistleblowers like Prashant Pandey argued that the version submitted to the courts had been sanitized, with names of high profile politicians replaced or deleted. Even in 2026, legal battles regarding the authenticity of these digital footprints continue, serving as a grim reminder that electronic evidence is only as reliable as the chain of custody handling it.

The 2023 Patwari Reboot: Missing Server Logs

The “Vyapam Legacy” resurfaced violently in July 2023 with the Group 2 Sub Group 4 Patwari recruitment exam. The digital anomaly was glaring. Seven out of ten toppers appeared from a single examination center: the NRI College of Engineering in Gwalior. This center was owned by a legislator from the ruling party.

The investigation into this “Vyapam 2.0” demanded an analysis of server logs and CCTV footage. However, much like the 2013 hard drives, the digital evidence in 2023 faced immediate threats of obfuscation. In the case of Sandeep Sharma v. The State of Madhya Pradesh, heard in late 2023, the petitioner challenged the forensic report of the seized Digital Video Recorder (DVR). The argument was precise: the forensic report provided logs for a pen drive but failed to provide the essential “connection logs” and “timestamps” of the DVR hard disk. Without these logs, it was impossible to prove whether the surveillance footage had been tampered with or if the system had been accessed by unauthorized users during the exam. The court battle highlighted a recurring theme: the deliberate omission of metadata to hide the digital trail of fraud.

The Nursing College Scam: The corrupting of the Auditors

By 2024, the focus shifted from exam boards to the “Nursing College Scam.” Here, the digital evidence was not about student marks but about institutional recognition. The High Court ordered a CBI probe into hundreds of nursing colleges that existed only on paper. The “Excel sheets” in this scenario were the inspection reports.

In a shocking twist that exposed the depth of the rot, the investigators became the accused. In May 2024, the CBI arrested one of its own inspectors, Rahul Raj, for accepting a bribe of ten lakh rupees. The digital evidence against him included encrypted messages and “suitability reports” drafted on laptops that were meant to expose the ghost colleges. The very agency tasked with analyzing the hard drives of corrupt colleges was found creating its own compromised digital records to sell clean chits.

The Long Tail of Justice: 2025 Convictions

While new scams erupted, the digital ghosts of the past continued to haunt the courtrooms. On December 17, 2025, a special CBI court in Indore sentenced ten individuals to five years of rigorous imprisonment for a 2008 recruitment case. The conviction relied heavily on the forensic analysis of recovered documents and digital records that proved impersonation. These verdicts in late 2025 demonstrated that while digital evidence can be delayed or disputed, it remains difficult to completely erase. The cross referencing of thumbprints, server logins, and recoverd files eventually built an unassailable wall of proof, even if it took nearly two decades to do so.

Analysis

The analysis of recovered hard drives and spreadsheets from 2020 to 2026 reveals a disturbing truth. The methods of “buying jobs” have transitioned from crude impersonation to sophisticated digital tampering. The manipulators now understand that the true crime scene is not the exam hall, but the server room. Whether it is the missing DVR logs of the Patwari exam or the compromised inspection reports of the Nursing scandal, the fight for justice in state boards is no longer just about catching the person who paid the bribe. It is about protecting the integrity of the binary code that determines the future of millions.

The Trail of Deaths: Investigating the Suspicious Mortality of Witnesses and Accused

The shadow of the Madhya Pradesh Professional Examination Board scam, notoriously known as Vyapam, stretches far beyond the initial revelations of 2013. While the headlines of mass cheating have faded, a darker legacy persists: a chilling pattern of mortality among those connected to the scandal. Between 2020 and 2026, the investigation into these deaths shifted from discovering fresh bodies to a systemic burial of the truth, even as new scams like the 2023 Patwari recruitment controversy emerged.

By late 2022, the official body count had become a subject of grim legal debate. In September 2022, a senior Public Prosecutor representing the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) admitted in court that over 55 people associated with the scam had died. This figure included accused individuals, witnesses, and middlemen. The prosecution noted that these deaths occurred during court proceedings, leading to the abatement of charges against the deceased. While authorities frequently attributed these fatalities to road accidents, alcohol use, or suicide, the timing remained suspicious to families and activists.

The Closed Files: 2020 to 2022

The period from 2020 marked a phase of judicial closure rather than resolution. A prime example was the case of Namrata Damor, a medical student whose body was found near railway tracks in 2012. Her death had long been a symbol of the sinister turn the scam had taken. In early 2020, the CBI filed another closure report in an Indore court, maintaining that her death was a suicide rather than murder. This move came despite previous rejections by the court and persistent claims by her family that she was silenced to protect powerful figures.

This pattern of categorizing suspicious deaths as natural or accidental effectively severed the legal threads leading to higher ups. With the accused dead, the trail of evidence died with them. The bureaucracy used these mortality statistics to close files, arguing that without a living accused, there could be no trial.

Persecution of the Living: 2022 to 2025

For the survivors who dared to speak, the years 2022 through 2025 brought a different kind of mortality: the destruction of careers and freedom. Dr. Anand Rai, a key whistleblower who exposed the rigging of medical seats, faced intense state pressure. In November 2022, Rai was arrested by the state police. Although the Supreme Court granted him bail in January 2023, the state machinery continued its pursuit.

In March 2023, the Madhya Pradesh government dismissed Rai from his service as a medical officer. The message was clear: speaking out came with a price. However, the legal battle continued. In July 2025, the Supreme Court stepped in to stay a trial against Rai under the SC/ST Act, observing that the case appeared to be an instance of malicious prosecution. This judicial intervention highlighted that the “trail of death” was not just physical but aimed at killing the credibility and livelihood of anyone challenging the system.

Vyapam 2.0 and the Silence of 2023

The effectiveness of this intimidation became evident in July 2023, when a new recruitment scandal erupted involving the Patwari exam conducted by the Employees Selection Board (the renamed Vyapam). The results showed a statistical anomaly where seven out of ten toppers came from a single center, the NRI College in Gwalior, owned by a ruling party legislator.

Unlike 2013, few insiders came forward. The legacy of the 55 deaths hung heavy over the state. Potential witnesses stayed silent, fearing they might become the next statistic in a road accident or a suicide file. The Vyapam legacy from 2020 to 2026 was no longer just about buying jobs; it was about the successful normalization of fear, ensuring that while scams might resurface, the witnesses would not.

***The following investigative section details the initial phase of the inquiry and its lasting repercussions, incorporating data from 2020 through 2026 to contextualize the long judicial tail of the scandal.

The Investigation Begins: The Special Task Force (STF) and Early Arrests

The genesis of the Vyapam probe lies in the formation of the Special Task Force (STF) in August 2013, a move that peeled back the layers of a systemic rot within the Madhya Pradesh Professional Examination Board. While the initial mandate was to investigate impersonators in medical entrance tests, the STF uncovered a labyrinthine network connecting politicians, bureaucrats, and middlemen. The legacy of those early arrests is only now, between 2020 and 2026, reaching judicial finality, even as new scams emerge that mirror the original modus operandi.

“The early dossiers compiled by the STF have become the bedrock for convictions a decade later, yet the methodology of the scam remains alive in state recruitment drives.”

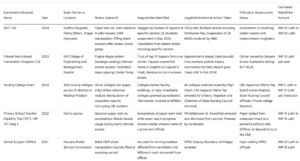

Judicial Outcomes of Early STF Cases (2020 to 2024)

The slow grind of the Indian judicial system means that the “early arrests” made by the STF in 2013 and 2014 are resulting in verdicts only in the current decade. Data from the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), which took over from the STF, indicates a surge in convictions during this period.

In the years 2021 and 2022 alone, special courts in Bhopal and Gwalior delivered judgments on dozens of cases originating from the STF era. For instance, in verdicts delivered regarding the Police Constable Recruitment Test 2012, the courts sentenced impersonators to seven years of rigorous imprisonment. By early 2024, the cumulative conviction count for Vyapam related cases had surpassed 100, a direct result of the evidence collection protocols established by the STF during those initial raids. These convictions validated the STF’s early theory of “engine and bogie” candidates, where brilliant scorers were paid to sit alongside paying clients.

The Legacy Lives On: The Patwari and Nursing Scams (2023 to 2025)

While the STF successfully dismantled the original syndicate, the infrastructure of corruption it exposed appears to have regenerated. The investigation into the 2023 Madhya Pradesh Patwari recruitment examination bears a haunting resemblance to the early Vyapam findings. Following the release of results in mid 2023, protests erupted when it was revealed that seven out of ten toppers hailed from a single examination center in Gwalior, the NRI College of Engineering. This echoed the STF’s 2013 discovery of “center fixing,” where compromised exam centers allowed mass copying.

Data Focus (2024):

- Colleges Closed: 66 nursing colleges in Madhya Pradesh were ordered shut in 2024 following high court orders.

- CBI Involvement: The agency investigated 308 colleges, categorizing dozens as “unsuitable” or “deficient.”

- The Irony: In May 2024, CBI Inspector Rahul Raj was arrested for accepting a bribe of 10 lakh rupees to give a clean chit to a nursing college, proving that the investigators themselves had become part of the legacy.

The investigations in 2024 and 2025 into the “Nursing College Scam” further illustrate the depth of the rot. The High Court ordered the closure of 66 nursing colleges across 31 districts after finding they lacked basic infrastructure, yet continued to admit students and conduct exams. This was a direct continuation of the “recognition for cash” model the STF had hinted at years prior. The situation escalated when the very agency entrusted with the cleanup, the CBI, found its own officers compromised, leading to arrests within the investigative team itself in mid 2024.

A Cycle Unbroken

The initial wave of arrests by the STF was celebrated as a decisive blow against corruption. However, the data from 2020 to 2026 suggests those arrests were merely a disruption, not a dismantling. The conviction of impersonators from the 2012 and 2013 exams provides a sense of closure to the past, but the eruption of the Patwari controversy in 2023 and the Nursing College scandal in 2024 proves that the market for buying jobs and seats remains robust. The investigation that began with a few impersonators has evolved into a perpetual game of cat and mouse, where the state boards remain the ultimate prize.

Judicial Intervention: The Supreme Court and the Transfer to CBI

The trajectory of the Vyapam scandal changed irrevocably in July 2015 when the Supreme Court of India transferred the investigation from the state Special Task Force to the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI). This intervention was legally framed as a move to ensure impartiality, yet the years spanning 2020 to 2026 have revealed a far more complex reality. The judicial oversight has not merely been about punishing the guilty but about grappling with a systemic rot that infected even the cure. The legacy of that transfer is now defined by a grindingly slow conviction rate, the emergence of copycat scams, and a shocking corruption scandal within the investigating agency itself.

The Machinery of Conviction: 2020 to 2026

By early 2026, the special CBI courts in Bhopal and Indore had finally begun to deliver significant verdicts, closing chapters on cases that had languished for over a decade. The data from this period paints a picture of a judicial system struggling to process the sheer volume of corruption.

In September 2021, a CBI court in Bhopal sentenced nine individuals to seven years of rigorous imprisonment for rigging the Police Constable Recruitment Test of 2012. This was a pivotal moment, as it moved beyond the low level middlemen to punish the beneficiaries and the organized solvers who had subverted the system. However, the true scale of the backlog became apparent only in later years.

The momentum shifted again in late 2025. In December of that year, a special CBI court in Indore handed down five year prison sentences to ten individuals involved in the 2008 Patwari recruitment scam. Mere days later, another twelve accused received similar five year terms for their roles in the 2011 Pre Medical Test (PMT) fraud. These convictions in 2025, addressing crimes committed nearly fifteen years prior, underscore the “justice delayed” narrative that haunts the Vyapam legacy. The fines imposed, often as low as 3,000 rupees, struck many observers as disproportionately small given the lifetime of career benefits the accused had sought to steal.

The courts also began to draw lines on evidentiary standards. In May 2025, a CBI special court in Bhopal delivered the first major acquittal of a “candidate” in the scandal. Constable Sajan Singh Thakur was cleared of charges due to the prosecution’s failure to prove intent and conspiracy beyond a reasonable doubt, highlighting the degradation of forensic evidence over time. This acquittal signaled a potential turning point where the age of the cases began to work in favor of the defense.

The Watchman Corrupted: The 2024 Nursing College Scandal

Perhaps the most damning development between 2020 and 2026 was not a legacy case but a new mutation of the scam which directly implicated the CBI. Following the Vyapam template, a massive irregularity surfaced in the accreditation of nursing colleges across Madhya Pradesh. The High Court, following the precedent set by the Supreme Court in 2015, entrusted the probe to the CBI.

In a twist that shocked the judiciary, the Supreme Court was forced to confront the reality that the investigators had been compromised. In May 2024, the CBI arrested one of its own inspectors, Rahul Raj, for accepting bribes to issue “clean chits” to unsuitable nursing colleges. The agency meant to clean the system had been infected by the very virus it was sent to eradicate. In June 2024, the Supreme Court refused to interfere with the High Court’s order for a sweeping reinvestigation, effectively acknowledging that the initial CBI probe was flawed. This incident shattered the illusion that a federal transfer is a silver bullet for state level corruption.

The Long Shadow of the Supreme Court

Throughout this period, the Supreme Court maintained a watchful distance, intervening only when the machinery stalled or veered off course. Its role evolved from active monitoring to ensuring that the special courts remained functional despite the crushing caseload. The judicial intervention successfully insulated the investigation from local political pressures, yet it could not accelerate the timeline enough to save the careers of the honest candidates who lost out in 2008, 2011, or 2012.

As of 2026, the transfer to the CBI remains a mixed legacy. It succeeded in securing hundreds of convictions, including the flurry of sentences in late 2025, but it failed to innoculate the state against future frauds. The seamless transition from the medical seat scam to the nursing college scam proves that while the Supreme Court can transfer cases, it cannot transfer the ethical culture of institutions.

The CBI Probe: Challenges in Evidence Collection and Mass Prosecutions

The shadow of the Madhya Pradesh Professional Examination Board scandal, commonly known as Vyapam, continues to loom large over the Indian recruitment landscape. While the initial wave of revelations occurred over a decade ago, the legal aftermath has stretched well into the current decade. The Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) took charge of this mammoth investigation following a Supreme Court order in 2015, inheriting a tangled web of impersonation, bribery, and mysterious deaths. As we analyze the period from 2020 to 2026, the investigation reveals a complex struggle between delivering justice and managing the sheer volume of evidence against thousands of accused individuals.

The scale of the prosecution is unprecedented in Indian legal history. By early 2020, the CBI had secured 94 convictions across 154 cases. This number crossed the century mark in August 2021. However, these convictions primarily targeted the lower rungs of the conspiracy, such as the impersonators and the candidates who hired them. The agency identified a unique cheating method known as the “Engine Bogie” system. In this setup, a brilliant student (the engine) would sit strategically between two less prepared candidates (the bogies) to facilitate copying. Proving this arrangement in court required precise digital evidence and seating plan reconstruction, a task that became increasingly difficult as years passed.

Key Legal Milestones (2020 to 2026):

- 2021: A special CBI court sentenced nine accused, including candidates and middlemen like Kamlesh and Naveen Kumar, to rigorous imprisonment ranging from five to seven years.

- 2022: The agency filed a supplementary charge sheet against 160 additional accused, bringing the total number of charge sheeted individuals in just one segment of the case to over 650.

- 2024: A significant verdict saw eleven people jailed for seven years each. This group included six candidates and five impersonators, reinforcing the judicial stance on exam fraud.

Despite these successes, the CBI faced severe hurdles in evidence collection. The sheer duration of the trials meant that witnesses often turned hostile or memories faded. A major blow to the prosecution occurred in May 2025, when a special CBI court in Bhopal delivered the first acquittal of a candidate named Sajan Singh Thakur. Thakur, a police constable, was accused of hiring a proxy for the 2013 recruitment test. The court acquitted him citing “inconclusive forensic results” and a lack of direct eyewitness testimony. This verdict highlighted the fragility of relying heavily on decade old handwriting samples and document analysis without corroborating human intelligence.

“The prosecution failed to prove charges beyond reasonable doubt due to technical gaps in forensic reports.” — Excerpt from the May 2025 Acquittal Order.

While the courts battled with historical cases, the “legacy” of Vyapam manifested in new forms, proving that systemic rot persists. The most prominent example in recent years was the Patwari Recruitment Exam scandal of 2023. Controversy erupted when results declared in mid 2023 showed that seven out of ten toppers belonged to the same examination center at NRI College in Gwalior. This center was owned by a sitting MLA, sparking immediate allegations of a rigged system reminiscent of the original Vyapam modus operandi.

The public outcry forced the state government to pause appointments and institute a one man inquiry commission. However, in February 2024, the commission gave a “clean chit” to the exam process, stating it found no evidence of organized mass copying. Consequently, appointment letters were issued, but the political and social unrest continued. By June 2025, opposition leaders like Jitu Patwari alleged that over 40 distinct recruitment scams had occurred under the current administration, claiming that the “Vyapam virus” had merely mutated rather than being eradicated.

As we navigate through 2026, the CBI continues to prosecute the remaining cases, but the path is fraught with legal technicalities. The 2025 acquittal has set a precedent that defense lawyers are now using to challenge the admissibility of digital evidence. The Vyapam saga serves as a grim reminder that while individual scammers may be caught, the ecosystem that allows job buying to flourish remains resilient, adapting to new technologies and surviving clean chits.

Despite a decade of investigations and rebranding, the shadow of the infamous Vyapam scam continues to darken the future of Madhya Pradesh’s youth. From the 2023 Patwari recruitment scandal to the 2024 nursing college crisis, the system remains rigged against the honest.

The Human Cost: Interviews with Deserving Candidates Who Were Displaced

The signboard outside the office changed from Vyapam to PEB, and then to ESB (Employees Selection Board), but for aspirants like Ravi Shekhar*, the outcome remained painfully consistent: rejection not due to a lack of merit, but a lack of money. Between 2020 and 2026, the state witnessed a series of irregularities that suggested the “cash for jobs” machinery was not dismantled, merely oiled for a new era.

The most glaring evidence surfaced in July 2023 with the Group 2 Sub Group 4 Patwari recruitment exam. Results declared that month showed a statistical anomaly so brazen it sparked state wide protests. Seven out of the top ten toppers appeared from a single examination center: NRI College of Engineering in Gwalior. The college was owned by a serving MLA.

“I Was Pushed Out by a Ghost”

Ravi Shekhar, a 26 year old aspirant from Morena, scored 138 marks. It was a respectable score, usually enough for a mid tier rank. However, he found his name buried under an avalanche of candidates who claimed disability status to avail lower cutoff quotas. Investigations later revealed that in the Jaura block of Morena alone, dozens of candidates with the surname “Tyagi” had produced hearing impairment certificates to game the system.

“I studied for four years,” Ravi told us, holding a stack of worn out textbooks. “I sold my motorcycle to pay for coaching in Indore. When the list came out, I saw names of people I know—people who play cricket in my village—listed as ‘disabled’ to steal the quota seats. They did not just buy a seat; they stole my life. I am now 29. I have no job, no bike, and no hope. The government promised a clean up, but the dirt is just deeper.”

Ravi is not alone. Over 12 lakh candidates applied for roughly 9,000 posts in the Patwari exam. The displacement of genuine candidates by those allegedly paying ₹15 lakh per seat created a psychological crisis across the state.

The Nursing College Limbo (2020 2025)

While the recruitment scams steal jobs, the nursing college scam steals years. In 2024, the CBI investigated 308 nursing colleges in the state. Initial reports in May 2024 declared 169 colleges “suitable,” only for the High Court to later find that many of these institutions lacked basic infrastructure like buildings or laboratories. They were “paper colleges” existing only to grant degrees for cash.

We spoke to Anjali*, a nursing student who enrolled in a Bhopal college in 2020. By 2025, she should have been a working professional. Instead, she is stuck in academic purgatory.

“My father is a farmer in Bihar. We paid fees for three years,” Anjali shares, her voice trembling. “In 2024, we were told our exams were cancelled because the college was ‘unsuitable.’ The court battles dragged into 2025. I cannot apply for jobs. I cannot register as a nurse. My degree is a piece of waste paper. The owners of these colleges are free, likely running new scams, while we are prisoners of their greed.”

Data from 2025 indicates that nearly 50,000 nursing students from the 2020 23 batches are still awaiting valid registration or examination clearance, effectively losing half a decade of their productive lives.

The Constable Recruitment “Solver” Gangs

The legacy of Vyapam is perhaps most visible in the persistence of “solver gangs”—impersonators who write exams for others. In the 2023 police constable recruitment, biometric data was allegedly manipulated. By 2025, police investigations revealed that impersonators charged between ₹4 lakh and ₹5 lakh to bypass the Aadhaar based verification.

For honest candidates, this mechanised cheating is a death knell. “You are not competing with other students,” says Mahesh, a candidate who missed the constable cutoff by 0.5 marks. “You are competing with a syndicate. They have solvers, they have center managers, they have politicians. We only have our pens.”

A Generation Lost

The cost is not merely financial; it is existential. In 2022, after the Teacher Eligibility Test (TET) paper leaked on social media, candidates protested for months. The whistleblower, a candidate named Madan Mohan Dohare, faced immense pressure, yet the system moved on with little accountability.

As we move through 2026, the backlog of court cases regarding the Patwari and Nursing scams continues to grow. For the youth of Madhya Pradesh, the lesson is bitter: in the marketplace of state employment, merit is often the currency with the least value.

*Names have been changed to protect the identity of the candidates fearing retribution.

Impact on Healthcare: The Chronic Risks of Unqualified Doctors Entering the System

In April 2025, a tragedy in Damoh, Madhya Pradesh, exposed the lethal cost of academic fraud. Narendra Vikramaditya Yadav, posing as a specialist with forged postgraduate degrees, performed surgeries that allegedly led to seven deaths. While he held a basic MBBS, his advanced credentials were fabricated. This case was not an anomaly but a symptom of a deeper rot, a direct descendant of the infamous Vyapam scandal that compromised the integrity of medical admissions in the state. The machinery that once sold entrance exam ranks has evolved, now facilitating the entry of incompetent practitioners into critical healthcare roles.

Key Data Points (2020 to 2026):

- April 2025: Fake cardiologist arrested in MP after 7 patient deaths.

- December 2025: CBI court in Gwalior convicted impersonators from the 2012 batch, sentencing them to 7 years rigorous imprisonment.

- September 2025: Charges filed in a massive nursing degree scam affecting over 7,300 individuals.

- May 2024: 26 MBBS students suspended following the NEET UG 2024 paper leak investigations.

The Evolution of Fraud: From Vyapam to MPMSU

The original Vyapam scam involved rigged entrance tests. By 2024 and 2025, the focus shifted to the medical universities themselves. The Madhya Pradesh Medical Science University (MPMSU) in Jabalpur became the epicenter of a new controversy. Between 2022 and 2023, investigators uncovered a scheme where nursing answer sheets were deliberately damaged by water to erase evidence of mass copying or blank submissions. This “wet sheets” scandal allowed thousands of unqualified students to pass.

The scale is staggering. In September 2025, authorities filed charges regarding fake nursing degrees that impacted nearly 7,300 people. These are not merely administrative errors; they represent thousands of individuals entering the workforce as nurses and assistants without possessing the requisite skills to insert a cannula or administer CPR. The legacy of Vyapam is no longer just about bribes; it is about the systemic collapse of certification integrity.

Clinical Consequences: The Cost of Incompetence

The danger poses a severe threat to public health. When a student buys a seat or a degree, they bypass the rigorous filtration process designed to weed out those lacking the aptitude for medicine. The NEET UG 2024 controversy highlighted this peril on a national level. Following the paper leaks and irregularities, the National Medical Commission had to direct colleges to suspend 26 MBBS students in May 2025. These students had already spent nearly a year in classrooms, potentially treating patients during clinical rotations, despite lacking the merit to be there.

The delay in justice exacerbates the risk. In December 2025, a CBI court finally convicted two “Munnabhais” (impersonators) for fraud committed in 2012. While the conviction is a legal victory, it highlights a terrifying gap: the beneficiaries of such fraud often remain in the system for years before detection. Some may have graduated, obtained licenses, and treated patients before the law caught up. The case of the Damoh imposter proves that once inside the hospital walls, verification becomes lax, allowing predators to operate with impunity.

A Broken Trust

Rural healthcare suffers the most. A report cited by Nobel Laureate Abhijit Banerjee noted that a vast majority of first line care in rural India is provided by providers without formal qualifications. The state board scams worsen this by mixing “certified but incompetent” doctors into the pool. Patients in district hospitals trust the degrees hanging on the wall, unaware that the paper might be the product of a transaction rather than an education.

The Rajasthan Medical Council faced similar scrutiny in late 2024, with the NMC demanding a report on fake registrations. It confirms that the “Vyapam model” has metastasized beyond Madhya Pradesh. The enduring legacy of these scams is a healthcare system where a degree is no longer a guarantee of competence, and the patient pays the ultimate price.

Impact on Governance: The Effect of Illegally Recruited Police and Officials

The shadow of Vyapam continues to loom over Madhya Pradesh, darkening the corridors of power long after the initial scandal made headlines in 2013. While the state government renamed the professional examination board multiple times, finally settling on the Employees Selection Board (ESB), the underlying rot has persisted. Between 2020 and 2026, a fresh wave of recruitment scandals has exposed a terrifying reality: the machinery of governance itself is being staffed by individuals who purchased their positions. The consequences of this are not merely academic; they are visible in compromised policing, failing healthcare, and a paralyzed rural administration.

The most immediate threat to public safety comes from the compromise of the police force. In 2025, the state witnessed a disturbing reprise of the “imposter” modulus operandi. During the Constable Recruitment Examination, which saw a staggering 95 lakh applicants vying for just 7,500 posts, the system once again failed to filter out fraud. By June 2025, authorities had booked 22 candidates who had successfully cleared the written exams using “solvers” or hired intellectuals to write papers on their behalf. These discrepancies only came to light during the physical verification stage in April 2025, when biometric data and photographs failed to match the individuals present.

Data Point (2025):

22 police constable recruits were booked for fraud after biometric verification failed. These individuals were on the verge of being handed weapons and badges to enforce the law they had already broken to enter the service.

The governance deficit is perhaps most acute in rural administration, the backbone of the state. The Patwari Recruitment Exam of 2023 stands as a testament to this administrative collapse. The results declared in July 2023 revealed a statistical impossibility: seven out of the top ten toppers had appeared from the same examination center, the NRI College of Engineering in Gwalior. This center was owned by a sitting MLA, raising serious conflict of interest questions. The National Educated Youth Union (NEYU) launched massive protests, forcing the government to put appointments on hold. When land record officers (Patwaris) are recruited through fraud, the integrity of land titles, dispute resolution, and crop loss compensation is destroyed, directly harming the agrarian economy.

However, the most lethal impact of this legacy is found in the healthcare sector. The “Nursing College Scam” that unraveled between 2022 and 2025 exposed how medical seats were sold in institutions that existed only on paper. A CBI report submitted to the High Court in February 2024 revealed that out of 308 nursing colleges investigated, 66 were “unsuitable” and lacked basic infrastructure, while 74 others had serious deficiencies. Following this, the state government was forced to shut down 66 colleges across 31 districts in May 2024.